Prev Page--Introduction || Next Page--Structure, Development, Distribution

The Rock Formations

The sedimentary rocks, including those exposed at the surface and those penetrated in wells in this part of Kansas, range in thickness from about 2,800 feet in east-central Greenwood County to more than 4,500 feet in the northwestern part of this county and in the northeastern part of Butler County. According to Kellett (1932) they are 3,500 to 4,000 feet in thickness at most places. A detailed study was made only of the portion of the sedimentary sequence that contains the shoestring sand lenses and beds. The Council Grove group of the Permian (?) system (SEE NOTE) is included in the portion of the sequence studied. It is exposed in several shoestring sand oil fields in the western part of Greenwood County. The columnar section shown in figure 2, largely after Kellett (1932), shows the general character of the main divisions of the stratigraphic column.

[Note: Following present usage of the Kansas Geological Survey the rocks of the Big Blue series, previously classed as Permian, are here designated as Permian (?) in order to indicate that, although they have generally been considered as Permian, there is now doubt as to proper definition of this term in Kansas. R. C. Moore, State Geologist.]

Figure 2--Columnar section of rocks in Greenwood and Butler counties, Kansas. (Classification of Pennsylvanian and Permian rocks after Moore, Elias, and Newell [1934]). The United States Geological Survey classes Permian, Pennsylvanian and Mississippian as series in the Carboniferous system.

Pre-Cambrian Rocks

The sedimentary rocks in Kansas are underlain at varying depths by igneous and metamorphic rocks. [Note: Igneous rocks comprise one of the three main classes of rocks that constitute the earth's crust; the other two are the metamorphic and sedimentary classes. Igneous rocks are those that formed by the cooling and solidification of molten masses. Metamorphic rocks are those that were originally either igneous or sedimentary, but were subsequently so much changed in form by heat and pressure that they no longer resemble their original character. The sedimentary class includes rocks derived from preexisting rocks; stratified rocks, such as limestone, shale and sandstone, that occupy practically the entire surface of Kansas, belong to this class.] But little is known about the distribution of the several types of igneous and metamorphic rocks in Kansas, because they are buried by a thick column of sediments, and so they are collectively referred to as the "crystalline and metamorphic complex," or, because of their position beneath the comparatively regular stratified rocks, as the "basement complex." Our only direct knowledge of these rocks has come from studies, by geologists (Haworth, 1915; Powers, 1917, p. 146-150; Wright, 1917, p. 1113-1120; Taylor, 1917, p. 111-126; Moore, 1918, p. 98-113; Moore, 1920a, p. 255-261; Moore, 1920b, p. 9; Moore and Haynes, 1917, p. 140-173; Fath, 1920, p. 25-27; Greene, 1925, p. 351-354; and Landes, 1927, p. 821-824) of drill cuttings from wells that have been drilled through the sedimentary sequence into the complex beneath. These studies show that these rocks consist chiefly of granite and schist, but also include quartzite, quartz porphyry, diabase, and other rocks; that their upper surface is an ancient irregular land surface with considerable relief that was subjected to the agencies of erosion for a very long time. These rocks, which are, therefore, very old, may be regarded as forming an irregular floor or basement upon which the sedimentary strata accumulated. They are, as previously stated, not exposed at the surface any place in Kansas, but they come to the surface in Missouri, where exposures show that they are overlain unconformably by rocks of Cambrian age. Studies of samples from wells in Kansas show that Cambrian and younger rocks unconformably overlie them here. These ancient basement rocks are referred to the pre-Cambrian division in the time scale, which merely means that their time of origin is prior to the Cambrian period of the Paleozoic era.

In general the pre-Cambrian basement is not so deep below the surface in eastern as in western Kansas, and is not so deep in northern as in southern Kansas. A well drilled a few miles southwest of Fort Scott, in Bourbon County, near the eastern boundary of the state, encountered the basement complex a little below a depth of 2,000 feet (Kellett, 1932); but a well drilled recently in Finney County, in the southwestern part of the state, to a depth of 5,872 feet, and another drilled nearby in Clark County to a depth of 6,906 feet, did not pass through the sedimentary rocks. A sufficient number of wells have, however, penetrated the uppermost part of the basement complex in the eastern half of the state so that information is available for showing that an old ridge of low hills, commonly referred to as the Nemaha granite ridge (Moore and Haynes, 1917, p. 81, 82, 140-173; Moore and Landes, 1927, p. 72, fig. 54), extends from Oklahoma in a north-northeasterly direction across Kansas into Nebraska. The ridge crosses the central part of Butler County, passing beneath Augusta, and just west of El Dorado, both of which are only a few miles west of some of the shoestring sand bodies. The granite surface of the Nemaha granite ridge lies at a depth of only about 600 feet in Nemaha County, near the northern boundary of the state, but as the ridge is followed toward the south it becomes deeper and deeper. Near El Dorado it lies at a depth of about 2,700 feet, and it is still deeper to the southwest of that place. The Nemaha granite ridge is of interest in connection with the study of the shoestring sand lenses because it probably was subjected to minor crustal movement during the time the Cherokee shale, which contains the shoestring sand bodies, was accumulating in Kansas, and because it, therefore, may have influenced the distribution of sediments in Butler and Greenwood counties and in adjacent areas. Geologic evidence furnished by rock samples from wells indicates that the Nemaha granite ridge was not in existence until Late Mississippian or Early Pennsylvanian time (Moore and Haynes, 1917, p. 172).

Cambrian and Ordovician Systems

Well records show that massive beds of dolomite, limestone, and sandstone, with a total thickness of 700 to 1,000, feet, referred to the Cambrian and Ordovician systems, overlie the pre-Cambrian complex in Greenwood and Butler counties, but the rocks of these ages are locally absent over the Nemaha granite ridge in Butler County. These rocks have not been subdivided in detail in this part of Kansas, although work by McQueen (1931) in Missouri, which he recently extended into Kansas, indicates that they probably can be subdivided and correlated with subdivisions that have been recognized on the surface in southwestern Missouri. McQueen's correlations are based largely upon the study of siliceous residues that are obtained by boiling rock samples in acid, and he has found that each formation has distinctly characteristic residues. By a study of residues obtained from drill cuttings and from outcrop samples he has identified the subdivisions of the Cambrian and Ordovician rocks throughout much of Missouri, where they are concealed beneath younger beds. In 1931 McQueen (Folger, 1931) extended his work into Leavenworth, Jefferson and Shawnee counties, in northeastern Kansas, by examining cuttings from the No. 1 Oak Mills well of the Indian Mounds Oil Co., in sec. 13, T. 7 S., R. 21 E., from the No. 1 Edwards well of the Northern Counties Oil & Gas Co., in sec. 13, T. 9 S., R. 19 E., and from the No. 1 Hummer well of Forrester et al., in sec. 14, T. 11 S., R. 16 E. In 1932 McQueen (Kellett, 1932) studied cuttings from the Stephenson No. 1 well of the Oklahoma Natural Gas Co., drilled in sec. 16, T. 26 S., R. 24 E., Bourbon County, in southeastern Kansas. In the northeastern Kansas area the Lamotte, Bonneterre and Eminence formations of the Cambrian system were recognized by McQueen and the Ordovician system was divided by him into the Gasconade-Van Buren, Roubidoux, Cotter, St. Peter, Decorah, Galena and Maquoketa (sic) formations. In Bourbon County the Cambrian and Ordovician systems are represented by about 900 feet of dolomite, sandstone and limestone. The lower 350 feet of this sequence has been subdivided by McQueen from the base upward into the Lamotte, Bonneterre, Eminence, and Proctor formations (Dake, 1930; Bridge, 1930) of the Cambrian system; and the upper 550 feet has been subdivided by him into the Gunter, Gasconade-Van Buren, Roubidoux, and Cotter-Jefferson City formations of the Ordovician system. The uppermost formations recognized in northeastern Kansas are, therefore, not present in Bourbon County. Studies, have not been made in Greenwood and Butler counties for subdividing the Cambrian and Ordovician rocks to a portion of which the term "siliceous lime" is in common use, but some geologists, who recognize that these rocks are equivalent to parts of the Arbuckle limestone of southern Oklahoma, apply to them the name Arbuckle limestone.

Studies of drill cuttings made by Messrs. McClellan, Howell, and others have shown that at some localities in southern Greenwood County and southeastern Butler County only the "siliceous lime" is present, but that throughout much of the remainder of the two counties the "siliceous lime" is overlain by a sandstone succeeded by a limestone. The sandstone is commonly referred to as Simpson sand, St. Peter sandstone, or "Wilcox" sand, and the limestone as the Viola limestone--names, except the St. Peter, that are applied to parts of the Ordovician system in Oklahoma. The correlation and distribution of these beds in Kansas and Oklahoma have been discussed by Barwick (1928, p. 177-199), Edson (1929, p. 441-458), McClellan (1930, p. 1535-1556), Howell (1932), and others.

Mississippian System

[Note: The U. S. Geological Survey classifies Mississippian as a series of the Carboniferous system.]

Rocks of Silurian and unquestioned Devonian age, which normally directly overlie Ordovician rocks, appear to be absent (McClellan, 1930) everywhere in Greenwood and Butler counties, although they are known to be present in other parts of the state. The Ordovician beds in the two counties are directly overlain by about 100 feet of black and gray shale, which is widespread, and has a remarkably uniform thickness. It is known as the Chattanooga shale (classified by the U.S. Geological Survey as Devonian [?]) in southern Kansas and in northern Oklahoma. Northward and northwestward in Kansas beds of gray shale that may be somewhat younger than or in part equivalent to the Chattanooga shale occupy approximately this position in the stratigraphic column (Leatherock and Bass, 1936, p. 99-100).

The unquestioned Mississippian rocks in this area are about 300 feet thick, and are composed largely of gray and dark gray limestone that contains much chert, especially in the uppermost part. They are locally absent over the Nemaha granite ridge. They are commonly called the "Mississippi lime," and are one of the most widely recognized buried rock units in Kansas. In northeastern Oklahoma and in Missouri, where they are exposed, they have been divided into a number of units; but little work has been done in Kansas in an attempt to correlate most of the concealed rocks of Mississippian age with the recognized units in Oklahoma and Missouri.

Pennsylvanian System

[Note: The U. S. Geological Survey classifies Pennsylvanian as a series of the Carboniferous system.]

The Pennsylvanian rocks of Greenwood and Butler counties consist of interbedded shale and limestone, and minor amounts of sandstone, and a very little coal, having a total estimated thickness of 2,150 feet. The thickness of the rocks of this system increases toward the southeast. Locally, over the Nemaha granite ridge in Butler County, it is about 400 feet less in thickness than the average thickness in the region. Most of the Cherokee shale, the lowermost formation, is absent there (Reeves, 1929, p. 161). The Pennsylvanian rocks are separated from the Mississippian rocks by an unconformity; the relief on the surface of the Mississippian, as indicated by well records, rarely exceeds 100 feet in a township.

Moore and Condra (1932) have recently proposed to rename most of the subdivisions of the Pennsylvanian rocks in Kansas on the basis of recent field work by them and other members of the Kansas and Nebraska Geological Surveys' staffs. The classification and nomenclature of the Pennsylvanian and Permian rocks in this report follows that of the Kansas Geological Survey (Moore et al., 1934) published in 1934. The classification used here differs somewhat from that given in former reports of the United States Geological Survey, and these differences have not been considered and adopted by the United States Geological Survey.

Under the present classification of the Kansas Geological Survey, the Pennsylvanian-Permian boundary is lowered from the contact of the Elmdale shale with the Cottonwood limestone of former Kansas geologic reports to an unconformity that in most nearly complete sections occurs between the Brownville limestone, below, and the Towle shale, above. In northwestern Greenwood County, where these rocks are exposed, the boundary has been lowered about 260 feet. This change transfers from the Pennsylvanian to the Permian the Eskridge shale, Grenola limestone, Roca shale, Red Eagle limestone, Johnson shale, Foraker limestone, and the entire Admire group, which is defined to include the beds from the unconformity beneath the Towle shale to the base of the Foraker limestone.

Des Moines Series

The Des Moines series includes the beds in the lower part of the Pennsylvanian system of Kansas, extending from the unconformity between the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian rocks upward to another unconformity that marks the boundary between the Marmaton group and the Bourbon formation. The Des Moines series is divided into two main parts, the lower consisting mostly of shale (Cherokee shale) and the upper containing prominent limestones interbedded with shale (Marmaton group).

Cherokee Shale

The shoestring sand lenses (known to operators in Kansas and Oklahoma as the Bartlesville sand) occur in the lower part of the Cherokee shale, which, in Kansas, is the lowermost formation of the Pennsylvanian system. The Cherokee shale overlies the "Mississippi lime" unconformably, but the strata above and below the unconformity are essentially parallel except at a few places. In the Greenwood-Butler County region the Cherokee is composed of light and dark gray shale, with lesser amounts of black shale, lenses of sandstone, and a few thin beds of limestone, red rock, and coal; shale which varies somewhat in composition and color makes up by far the greater part of the formation. Well logs record much of the shale as light gray and fine-grained clay shale. Many areas contain some very fine-grained sandy shale. Some beds of black shale and dark blue shale are reported in much of the region; the beds of black shale are believed to be most abundant in the lower half of the formation in Greenwood and Butler counties. Haworth (1898, p. 23-24) describes the formation at the outcrop in southeastern Kansas as follows:

The character of the Cherokee shales varies materially, both vertically and longitudinally. Shale of almost all descriptions may be found. . . . Portions of them are as black as coal. . . . Variations may be noted through different degrees of black and gray and greenish gray into a very light-colored, ashen-gray shale. . . . Composition shows a great variation, ranging from a fairly good clay shale, composed almost entirely of clay, into a perfect sandstone, with all intervening grades.

Hinds and Greene (1915, p. 40) state that in western Missouri contemporaneous beds in the lower part of the Cherokee shale vary greatly from place to place; that the upper part of the formation consists of strata that are more uniform and can be identified throughout Missouri, and parts of Kansas and Iowa. The records of wells in the Greenwood-Butler County region indicate that there the lower part of the Cherokee shale varies less in character laterally than it does along the outcrops in western Missouri and eastern Kansas. Sandstone beds form as much as one-fourth of the total thickness of the Cherokee shale in only a few localities in Greenwood and Butler counties, and in most localities where the shoestring sands are present sandstone comprises only a fifth or less of the total thickness. The logs of some wells in these counties record no sandstone whatever in the Cherokee shale.

The shoestring sands, the subject of this report, are narrow elongated lenses in the lower part of the formation. Throughout the northern part of Greenwood County the sand lenses are separated from the underlying "Mississippi lime" by a thickness of shale varying from 50 to 150 feet, but averaging a little less than 100 feet. The sand bodies are separated from the underlying limestone by a thickness of shale less than 100 feet in southeastern Butler County, and actually rest directly on it in parts of the Keighley, Fox-Bush, and Smock-Sluss oil fields in that county. Red rock 10 to 30 feet in thickness is recorded at the horizon of the shoestring sands in the logs of most wells that are outside the shoestring oil fields, and so found no shoestring sands in southern Butler County, where only a small thickness of shale intervenes between the sand zone and the "Mississippi lime." The apparent absence of the lowermost part of the Cherokee shale, and the abundance of red rock at about the horizon of the shoestring sands in the southeastern part of Butler County suggests that a portion of the south half of the county may have been land during a part of the time that the Cherokee sea occupied Greenwood County and adjacent areas. The "Mississippi lime" would have formed the land surface of that time and the source (for a discussion of red rock derived from limestone, see Tomlinson, 1916, p. 153-179, 238-253) of the material for the red rock may have been old soils that were largely derived from the "Mississippi lime."

At places in the Greenwood-Butler County region, particularly in the eastern part of Greenwood County, a sandstone unit is present at the base of the Cherokee shale. It lies below the shoestring sands described here and is separated from them by beds of shale. In many parts of Kansas a conglomerate, composed largely of chert and lesser amounts of limestone, forms the lowermost beds of the Cherokee shale. Sandstone occurs locally above the main shoestring sand horizon, also, and contains commercially valuable amounts of oil in the Wiggins and Wilkerson fields in Greenwood County and at localities in northwestern Cowley County. The Wiggins and Gaffney fields, 6 to 12 miles north of Eureka, produce oil from beds of sandstone that occur 50 to 75 feet above the main shoestring sand horizon, and are known as the upper and lower Cattleman sands. Sandstone at about the horizon of the sand, in the Wiggins oil field is oil-bearing in the Wilkerson pool in secs. 6 and 7, T. 25 S., R. 9 E., also in secs. 9, 10, 15, and 16, T. 23 S., R. 10 E. Sandstone at approximately the horizon of the Wiggins sand is the chief oil reservoir in the Rock, Clarke and Smith fields in northwestern Cowley County. Thick beds of sandstone at about this horizon were found to contain water in several wells in the southern part of Lyon County. Even higher sands in the Cherokee shale are recorded in some well logs in the Greenwood-Butler County region, but they appear to be of only local extent. Beds of sandstone in the Cherokee shale are more numerous in eastern Kansas and in western Missouri than in the Greenwood-Butler County region. The sandstone content of the Cherokee increases greatly, and also the thickness of the formation increases, southeastward from Kansas into eastern Oklahoma.

The aggregate thickness of limestone in the Cherokee shale is even much less than that of sandstone. The records of most of the wells in Greenwood and Butler counties show no limestone, but there are some carefully kept logs which record thin beds of limestone in the upper half of the formation. Drillers have informed me that in many localities thin beds of limestone are present in the Cherokee shale, but the beds are as a rule so thin that they are regarded as of no importance and are therefore seldom recorded in the well logs. Thin beds of limestone that persist over wide areas occur in the Cherokee shale in western Missouri (Hinds and Green, 1915, p. 38-39) and southeastern Kansas (Haworth, 1898, p. 23-29) and are particularly well developed in northeastern Oklahoma, where the formation crops out, and west of the outcrops where the beds are penetrated by oil wells (Bass et al., 1936). Hinds and Greene (1915, p. 39) reported that the limestone beds in Missouri contain abundant invertebrate fossils, and Haworth (1898, p. 29) reported the limestone beds in Kansas to be fossiliferous. Several fossiliferous limestone beds occur in the Cherokee shale in northeastern Oklahoma and are recorded in most well logs.

Beds of coal ranging up to 5 feet thick, but more commonly 1 to 2 feet or less thick, occur throughout the Cherokee shale in the easternmost part of Kansas and in the western part of Missouri. Coal is mined from these beds at Pittsburg, Kan., and a number of other localities in southeastern Kansas, northeastern Oklahoma, western Missouri, and at Leavenworth and Lansing in northeastern Kansas. Thin beds of coal are recorded in well logs in a few localities in the Greenwood-Butler County region; the most abundant occurrence is in the Theta oil field in secs. 5 and 17, T. 22 S., R. 10 E., where coal overlies the producing sand of the oil field at a depth of about 2,300 feet.

A unit of red shale ranging up to 50 feet thick, but commonly only 5 to 15 feet thick, is present locally in the Cherokee shale in Greenwood, Butler, Cowley and other counties. It most commonly occurs at or close to the stratigraphic horizon of the shoestring sands in the localities that contain no sands, but other parts of the Cherokee shale contain thin beds of red shale in some localities. The areal distribution of the red shale that occurs at the horizon of the shoestring sands is patchy, and appears to be unsystematically distributed over the region. However, red shale at this horizon is fairly persistent in the southeastern fourth of Butler County.

The Cherokee shale ranges in thickness in Greenwood and Butler counties from a feather edge to a little more than 350 feet. The thickness of the Cherokee shale in eastern Kansas and northeastern Oklahoma is shown by a sketch map on Plate 1. It is very thin in some, and totally absent in other localities situated over the Nemaha granite ridge in northwestern Butler County. The formation thickens at a fairly rapid rate through the first few miles eastward from the granite ridge, thence at a less rapid rate eastward, the rate of thickening becoming very low in an eastward direction east of Butler County. The shale is 300 feet thick along the Greenwood-Butler County boundary, and it is 350 feet thick along the eastern boundary of Greenwood County. Because the shale directly overlies the irregular erosion surface on top of the "Mississippi lime," its thickness varies somewhat locally, but variations in thickness due to the relief on the Mississippian surface are rarely as great as 100 feet in a township.

The character of the sediments and the fauna and flora preserved in the rocks indicate that the Cherokee shale is composed of rocks that were deposited under a succession of alternating continental and marine environments. It is believed that the delicate balance between marine and nonmarine conditions in eastern Kansas was disturbed repeatedly during the long time in which the Cherokee shale was accumulating. That changing conditions prevailed during Cherokee shale time is indicated by (1) marine fossils that have been gleaned (Tarr, 1925, p. 350-351; Buchanan, 1925, p. 814) from well cuttings from the lowermost part of the formation, and (2) by the fossils reported (noted in unpublished reports of oil company micropaleontologists, based on studies of well cuttings) from limestone beds in the middle part of the formation, (3) by the lenticular character of the beds of sandstone closely associated with red rock, (4) by the lenses of coal, and (5) by the presence of fossil plants. The character of the sediments exposed in eastern Kansas and western Missouri indicates that the balance between marine and nonmarine conditions was particularly unstable in early Cherokee time. The more uniform and more widespread persistence of the strata in the upper part of the formation than in the lower part suggests that the marine waters were not only more widespread in late Cherokee time, but that the Cherokee basin had been leveled with sediments, permitting the accumulation of sheetlike deposits of uniform thickness and character. The widespread distribution of the coal beds that are so closely associated with beds of marine limestone in the Cherokee shale indicates that at times when the marine water body withdrew from eastern Kansas its shore was closely followed by freshwater swamps. The entire land area probably presented an expanse of swamps or marsh flats; the coal beds and plant fragments indicate that the land supported much vegetation.

Age of the Shoestring Sands--The shoestring sand bodies in the lower part of the Cherokee shale in Greenwood and Butler counties and adjacent areas are designated as the Bartlesville sand by operators, drillers, geologists and others connected with the production of oil in this region. This name implies that the sand bodies are of the same age as the Bartlesville sand of the vicinity of Bartlesville, Okla., which has been an important producer of oil and gas for many years. The Bartlesville sand near the town of Bartlesville occurs in the lower part of the Cherokee shale, but is separated from the "Mississippi lime" by a relatively small thickness of shale. The earliest mention of the term Bartlesville sand found by me in a geologic publication is that by Buttram in 1914 (p. 43), but he indicates that the name had been in common use for some time prior to 1914. As oil and gas development progressed rapidly in northeastern Oklahoma and southeastern Kansas 20 or more years ago, most of the oil was found in beds of sandstone in the lower part of the Cherokee shale. In each new field the name Bartlesville was applied to the sand, although it was recognized fairly early by several geologists that not all the sands called Bartlesville are equivalent, but that they are really numerous lenses occupying the same general stratigraphic position in the Cherokee shale. Berger stated, in 1918, in discussing a paper by Greene (1918, p. 123) which describes the geology of eastern Osage county, Oklahoma, that what was considered the Bartlesville sand in Osage and Washington counties is not the same sand throughout; and that any producing sand found between 200 and 600 feet below the Fort Scott limestone was called the Bartlesville. Ross (1919, p. 184) also expressed the opinion that oil or gas productive sands, that seem in a broad way to occupy stratigraphic positions similar to that of the productive sand at Bartlesville, are referred to as the Bartlesville sand, even though they probably are not equivalents.

Greene (1918, p. 118-119) correlated productive sands in eastern Osage County with the Bartlesville sand in 1918, and stated that in all probability the Clear Creek sandstone that occurs uniformly 45 feet above the Mississippian rocks and crops out in Vernon and Barton counties, Missouri, is the equivalent to the Bartlesville sand. About this time detailed stratigraphic studies in northeastern Oklahoma and southeastern Kansas were being conducted by A. W. McCoy, and others working with him, along the outcrops of the Cherokee shale. Also, the records of hundreds of wells were studied by them. The results of these studies convinced McCoy (personal communication) that the Bartlesville sand accumulated along the margins of the Cherokee sea during the early stages of its northward advance in a broad trough extending through eastern Oklahoma into southeastern Kansas. The advance of the sea was very slow, and it halted at times, and the shore of the sea migrated back and forth over a narrow strip of country. During periods when the shore was stationary the Bartlesville sand accumulated. This strip of country, as described by McCoy, includes eastern Osage County and western Washington County, Oklahoma, and extends thence northeastward into Kansas across southeastern Montgomery County, and across Labette County into northwestern Neosho County to the vicinity of Chanute, whence it passes eastward to possibly the westernmost part of Missouri, where it turns southward and follows along or near the Missouri-Kansas boundary. McCoy (personal communication) agrees with Greene that the Clear Creek sandstone which crops out in Vernon and Barton counties, Missouri, and which there supplies many oil seeps, is probably the equivalent of the Bartlesville sand.

The supposition is that the advance of the sea upon eastern Kansas was continued subsequent to the deposition of the Bartlesville sand, but was no doubt accomplished very slowly and accompanied by many fluctuations of the shore lines. As the water advanced over the featureless plains that are believed to have characterized the region, the old soils that had accumulated on the land, and sediments from more remote areas, brought to the sea by rivers, were washed into the sea and distributed widely by waves and currents to form the Cherokee shale. The close association of marine and nonmarine beds and the widespread distribution of some of the beds suggest that the sea was at all times very shallow. By the time the advancing northwestern shore of the sea had reached the Greenwood-Butler County region the Bartlesville sand of northeastern Oklahoma and southeastern Kansas was buried beneath younger mud and sand, and the country occupied by the old Bartlesville shore line was out in the midst of the Cherokee sea, which had expanded far beyond its former boundaries and now occupied most of eastern Oklahoma, eastern Kansas, western and northwestern Missouri. During periods when the shore line was temporarily stationary, the sand deposits were made in the Greenwood-Butler County region and western Osage and eastern Kay counties, Oklahoma (includes oil productive sands of the Burbank, South Burbank, and Naval Reserve oil fields).

In other words, as pointed out by Weirick (1932, p. 25-28), the shoestring sands of western Osage and eastern Kay counties, Oklahoma, and Cowley, Butler and Greenwood counties, Kansas, are younger than and stratigraphically higher than the Bartlesville sand of eastern Osage-Washington counties, Oklahoma, and also younger than the sands in the southeasternmost part of Kansas.

Marmaton Group

The Marmaton group as restricted by Moore et al. (1934) consists of about 250 feet of alternately bedded limestone and shale overlying the Cherokee shale. The lowermost formation is the Fort Scott limestone, one of the most widely recognized formations in wells throughout eastern Kansas and northern Oklahoma. Most of the individual members in the Marmaton group cannot be correlated readily in well logs throughout large areas, but the group as a whole is persistent and recognizable in much of the state.

Missouri Series

The Missouri series, as redefined by the Kansas Geological Survey (Moore et al., 1934), includes the beds from the unconformity at the top of the Marmaton group to another unconformity which occurs between the Stanton limestone or overlying rocks of the Pedee group, below, and sandy deposits of the Douglas group, above. The Missouri series is divided in eastern and northeastern Kansas into the following main parts, named in upward order: Bourbon formation, Bronson group, Kansas City group, Lansing group, and Pedee group. In the Greenwood-Butler County area it is not possible to recognize clearly all of these divisions in the well logs.

Bourbon Formation

The name Bourbon formation has been applied (Moore, 1932, p. 89) to the beds, about 200 feet thick on the outcrop in eastern Kansas, that overlie the Marmaton group as now defined. Equivalent beds in Greenwood and Butler counties appear to be about 50 feet thick. In former reports the Bourbon formation was regarded as a part of the Marmaton group. Sandy shale and sandstone, commonly reported in logs of wells drilled in eastern Kansas, have been assumed to, overlie the disconformity at the base of the Bourbon formation, and on this basis Kellett (1932) has traced the Bourbon beds from well to well from near the outcrop westward across Greenwood and Butler counties into the western part of McPherson County.

Bronson Group

The Bronson group, about 150 feet thick in Greenwood County, consists mostly of thick beds of limestone. The name Bronson is applied to the lower prominent limestones and included shales that formerly have been included in the Kansas City formation. The Bronson limestones can be recognized as a distinct group throughout much of Greenwood and Butler counties.

Kansas City Group

The Kansas City group includes a series of beds about 150 feet thick, composed largely of shale in the region of Greenwood and Butler counties, although it contains thick beds of limestone farther east in the state. A persistent limestone unit about 25 feet thick, that is recorded in most wells in Greenwood County as occupying a position 25 to 35 feet above the base of the group, is correlated with the Drum limestone by Kellett (1932). The main shale unit that overlies the Drum limestone was included with the Lansing group in some former reports (Fath, 192o, p. 41-42; Bass, 1929, p. 34-35) but the Drum limestone was included in the Kansas City group.

Lansing Group

The Lansing group, approximately 135 feet thick, overlies the Kansas City group and, according to the records of wells drilled in Greenwood and Butler counties, is composed almost entirely of limestone. It contains considerable shale at the outcrop, but is reported in well logs as limestone, and is a persistent and widespread unit.

In the southern part of Greenwood and Butler counties and on southward in Cowley County the thick limestone beds of the Lansing group, and to some extent those of the Bronson group, contain increasing amounts of sandstone and sandy shale (Bass, 1934, p 34-35). West of the region of this report the (new) Kansas City group contains an increasing proportion of limestone so that the Bronson, Kansas City, and Lansing groups, being practically all limestone, as reported in well records, are commonly combined in one thick limestone unit. The Kellett (1932) cross section shows that these groups coalesce in T. 22 S., R. 3 E., Marion County. A study of logs of wells in the region extending southwest from Marion County shows that a line drawn from T. 22 S., R. 3 E., southwestward through Valley Center, Garden Plain, Cheney, and thence to about the middle of the south boundary of Kingman County, forms approximately the boundary between a region to the south and east in which the three groups can be separated readily by the presence of shale "breaks," and a region to the northwest where all three groups are combined as one limestone unit which may be designated as the Bronson-Lansing limestone.

Pedee Group

The Pedee group comprises shale, together with some limestone and sandstone, that conformably overlies the Lansing limestone. It is unconformably overlain by sandstone and shale belonging to the Douglas group, which is the lowermost division of the Virgil series. In many localities it is not possible to identify in well records the unconformity at the top of the Pedee group, but according to the Kellett (1932) cross section the Pedee is recognizable in part of Greenwood County. It is convenient to designate the combined Pedee and Douglas beds as Pedee-Douglas in well records which do not furnish indication of the location of the boundary.

Virgil Series

The Virgil series, according to classification of the Kansas Geological Survey, includes the uppermost beds of the Pennsylvanian system, extending from the unconformity at the base of the Douglas group to another unconformity that is recognized above the Brownville limestone. This series contains the Douglas group at the base, the Shawnee group in the middle, and the Wabaunsee group at the top.

Douglas Group

Shale, sandstone, and lesser amounts of limestone, with an aggregate thickness of about 300 feet in the Greenwood and Butler County area, overlie the Lansing group. Thick beds of sandstone that carry water most commonly occur in the lower 100 feet of this sequence, and a persistent zone of red shale occurs in the upper 100 feet of the sequence in southern Kansas and northern Oklahoma. The upper part of these sandstones and shales, and in some places all of them, belong to the Douglas group. As previously noted, shale that appears referrable to the Pedee group occurs in Greenwood County, but farther west, in Butler County, sandstone of the Douglas group rests directly on beds of the Lansing group. Sandstone and shale of the Douglas group are exposed in southeastern Greenwood County.

Shawnee Group

The Shawnee group in Greenwood and Butler counties embraces about 400 feet of interbedded limestone and shale. This group includes the strata from the base of the Oread limestone to the top of the Topeka limestone. It contains such widely known formations as the Oread, Lecompton, Deer Creek and Topeka limestones, which have furnished key beds for surface geologic mapping in eastern Kansas carried on by many petroleum geologists. These formations exhibit especially well certain rhythmic successions of shale and limestone beds, which have been described by Moore (1931, p. 247-257). The Shawnee group crops out in the eastern part of Greenwood County (Haworth, 1937), but was not studied in connection with the shoestring sand investigation.

Wabaunsee Group

The Wabaunsee group includes 450 or more feet of strata between the Topeka limestone and a disconformity just above the Brownville limestone. Shale is the predominant rock, but there are thin beds of coal, minor amounts of sandstone, and persistent units of fossiliferous limestone that characteristically weather tan to tannish brown. The Wabaunsee group as a whole forms a broad lowland that occupies the surface of most of Greenwood County. Some of the limestone beds form fairly prominent ledges. The conspicuous ledge near Madison and in the Fankhouser oil field northeast of Madison, in northern Greenwood County, is formed by the Burlingame and Wakarusa limestones, formations in the Wabaunsee group.

Permian System

[NOTE: The rocks here designated under the term Permian system are those, (excepting certain beds at the base) that have long been classed in Kansas as Lower Permian). It now seems doubtful whether these beds are properly regarded as Permian, and until the problem of defining the type Permian system in Europe is worked out, it appears desirable to query the use of Permian as applied to the Big Blue series of Kansas. The U. S. Geological survey classifies the Permian as a series of the Carboniferous system. R. C. Moore, State Geologist.]

Only the three lower groups of the Permian system, with a combined thickness of approximately 700 feet, are present in the shoestring sand region of Greenwood and Butler counties.

Big Blue Series

The lower part, of the Permian system in Kansas consists of limestone and interbedded shale that is mostly of marine origin. These rocks are termed the Big Blue series. The upper part of the Permian consisting chiefly of red beds (Cimarron series), is not represented in the area treated in this report. The Big Blue series includes the beds from the unconformity between the Brownville limestone, or other uppermost Wabaunsee beds, and the overlying Towle shale to the top of the Wellington shale. It is divided into four groups, which, named in upward order, are as follows: Admire, Council Grove, Chase and Sumner.

Admire Group

The Admire group includes the lowermost beds of the Big Blue series, as now defined, extending from the unconformity above the Brownville limestone to the base of the Foraker limestone. The Admire beds crop out along the foot of the Flint Hills, at the base of the east-facing escarpment. They were not studied especially in the course of my field work.

Council Grove Group

The Council Grove group, particularly the lower half of it, was studied in detail because numerous beds of limestone make conspicuous outcrops in several of the shoestring sand oil fields. Detailed stratigraphic studies were made of the rocks of this group in and near the Thrall and Browning oil fields, in connection with the surface structural mapping of these fields. In order to correlate the beds exposed in the Thrall and Browning oil fields with those exposed on the Cottonwood river to the north and those exposed in Cowley County to the south and in northernmost Oklahoma, sections were measured at intervals of 5 to 10 miles, extending from the Cottonwood River to the Kansas-Oklahoma boundary. This correlation was necessary because the stratigraphic section exposed in Cowley County (Bass, 1929, p. 58-67) had been studied in detail and because many of the type exposures for the subdivisions of this group, as originally defined by Prosser, Beede and others, are in the Cottonwood Valley. The results of this study in the correlation of the rocks between the Kansas-Oklahoma boundary and the Cottonwood river valley are shown on Plate 2. All limestone units between the Admire group and the Morrill limestone were correlated in detail; not so much detail was obtained for the rocks above the Morrill limestone, although the Crouse limestone and a persistent limestone between the Morrill and the Crouse were identified in all measured sections. The upper part of the Council Grove group has been studied in Kansas by Condra and Upp (1931) who have given new names to many of the units.

Plate 2--Chart showing correlations of rocks exposed in oil fields in northwestern Greenwood County and adjacent region and key map showing locations of measured sections. Shoestring oil fields are shown in solid black on key map. [This image is also available as an Acrobat PDF file.] Stratigraphic classification after Moore et al. (1934).

Detailed Locations of Stratigraphic Sections

- The highway cut in the west slope of the big hill 1 mile east of Elmdale, and the west-facing slopes that extend southward from the highway for three-quarters of a mile: sec. 26 and 35, T. 19 S., R. 7 E.; also the west-facing slope and gulch in the SW sec. 11, the S2 sec. 10, and the E2 sec. 9, T. 20 S., R. 7 E., 3 miles south of the highway.

- The northward-trending gulch in secs. 12, 13, 24 and 25, T. 20 S., R. 9 E., 5 to 8 miles south and 2 miles east of Saffordville.

- The Browning oil pool in secs. 17, 18, 19, 20, 29 and 30, T. 22 S., R. 10 E.; particularly, the gulch in the NW sec. 17 and the NE sec. 18; the gulch south of the road in the NW sec. 21; the gulch in the SW sec. 21 and the SE sec. 20; the north-facing slopes in the N2 sec. 30, T. 22 S., R. 10 E.; and a gulch cut in the Wreford limestone in the SE SE sec. 36, T. 22 S., R. 9 E.

- The Thrall oil pool in secs. 28, 29, 31, 32 and 33, T. 23 S., R. 10 E.; particularly, the gulches in the NW sec. 5, T. 24 S., R. 10 E., in the N2 N2 sec. 33 and the S2 sec. 28, in the W2 NW sec. 27 and the E2 NE sec. 28, T. 23 S., R. 10 E. (lower part of the stratigraphic section). South of the Teeter oil pool, particularly in about secs. 28 and 33, T. 23 S., R. 9 E. (the upper part of the stratigraphic section).

- The Sallyards oil pool, particularly the gulches in the E2 sec. 34, the S2 sec. 35, and much of sec. 36, T. 25 S., R. 8 E. Road cut on U.S. highway 54 in NW sec. 6, T. 26 S., R. 9 E. (Foraker limestone).

- One mile north of 2 1/2 miles east of Beaumont; particularly the main gulch in S2 sec. 26, T. 27 S., R. 8 E., immediately south of state highway 96 where it descends the Flint Hills escarpment; and the gulch in the NW SW sec. 30, T. 27 S., R. 9 E., which is about a quarter of a mile southeast of the right angle turn to the north on highway 96.

- The Porter oil field; both sides of the east-west road in about sec. 24, T. 29 S., R. 8 E.

- Two miles northeast of Grand Summit station on both sides of the railroad tracks, and in the main gulch and its south-facing slopes, mostly in sec. 3, T. 31 S., R. 8 E.

- Two miles east of the Hooser-Cambridge secondary road, in a west fork of Otter Creek gulch, near the middle of the N2 sec. 6, T. 33 S., R. 8 E.

- About a mile south of the Kansas-Oklahoma state boundary, in a road cut on the Cedarvale-Foraker road, on a west fork of Ekley Canyon, about the section line between the SW sec. 16 and the NW sec. 21, T. 2? N., R. 7 E., Oklahoma.

The subdivisions of the lower half of the Council Grove group are characterized by thick beds of limestone in southern Kansas, each of which splits northward into two limestone members separated by shale. This characteristic feature is modified somewhat in the Foraker limestone, which splits into four limestone units instead of two.

Foraker Limestone--The Foraker limestone of southern Kansas (Bass, 1929, p. 45-52) is about 50 feet thick and is composed chiefly of thick beds of light-gray limestone. The limestone contains fusulinids in abundance in all beds and fossiliferous chert in some beds. This formation was identified at numerous places in the belt of country extending from its type locality (Heald, 1916, p. 21, 25) in Osage County, Oklahoma, northward to the Cottonwood River, a distance of about 100 miles, in a straight line. As shown on Plate 2, the amount of shale increases and the amount of limestone decreases toward the north, and the formation is divisible into several limestone and shale members which are, from the base upward, the Americus limestone, Hughes Creek shale containing the Thrall limestone bed, and the Long Creek limestone.

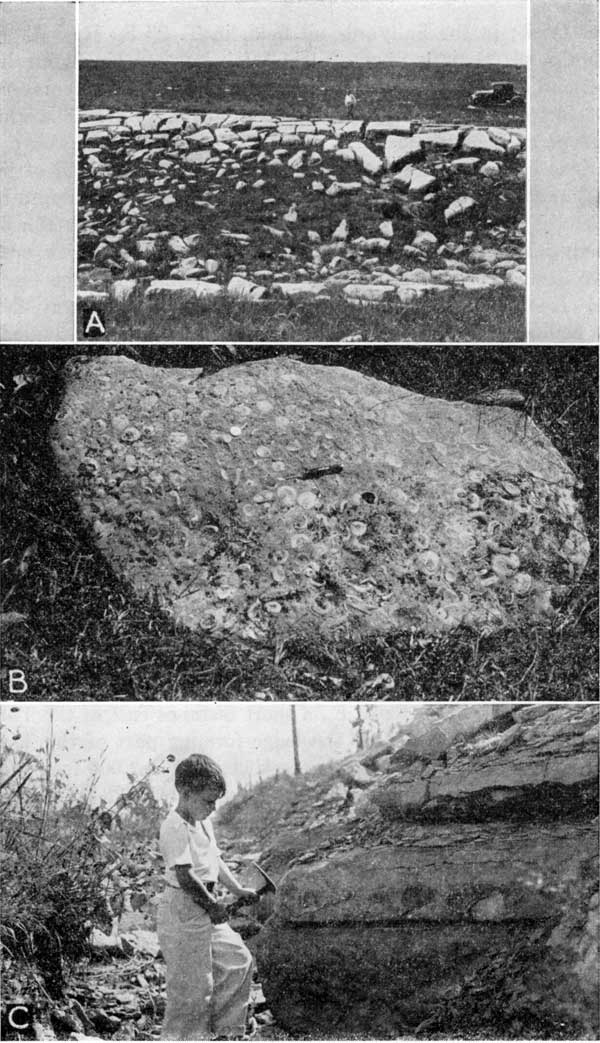

The two lowermost limestone beds, with the intervening shale, constitute the Americus limestone member (Bass, 1929, p. 50-52). The lower bed of the Americus limestone is massive, dense, bluish-gray, fossiliferous, and about 2 feet in thickness. It contains minor amounts of chert in some localities. Fossils are most numerous in the lowermost part of the bed. The limestone crops out as a hard, blocky rock that forms a prominent ledge. Thick blocks of limestone that have become separated from the main ledge and lie strewn on the slope below form a characteristic feature of the member. The smooth upper surface of the outcropping ledge makes an ideal key for structural mapping. The lower limestone is characteristically exposed in Greenwood County, about 200 feet southwest of the north quarter corner of sec. 21, T. 22 S., R. 10 E., about 200 feet south of the main road leading to the Browning oil field (see pl. 3); and in the southeast bank of the stream near the center of the NW sec. 5, T. 24 S., R. 10 E.; and on both sides of the gulch east of the center of sec. 5, T. 24 S., R. 10 E. (see pl. 5), about half a mile south of the Thrall oil field.

The shale between the two limestone units of the Americus limestone is gray to drab, and is in part limy; it is 6 to 8 feet thick near Elmdale (see column 1, pl. 2), 3 feet thick in the Thrall oil field (see column 4, pl. 2), and as much as 13 feet thick in the southern part of Cowley County and in the northern part of Oklahoma (see column 10, pl. 2).

The upper limestone of the Americus member is persistent from the Cottonwood River valley southward to the east-central part of Cowley County. It ranges in thickness from 1 foot 4 inches near Elmdale (see column 1, pl. 2) to 4 feet 5 inches near Grand Summit, in Cowley county (see column S, pl. 2). A short distance south of Grand Summit the limestone beds of the upper Americus coalesce with limy beds adjacent below and above, and the unit loses its identity. It consists of light gray abundantly fossiliferous limestone that is characteristically thinner bedded than the lower limestone of the Americus member and forms much less prominent outcrops than the lower limestone; in fact, in most localities in western Greenwood County it forms only a rocky shoulder a few feet above the ledge of the lower Americus. At the outcrops in southwestern Lyon County, shown in column 2 on Plate 2, the bed is blocky, similar to the lower Americus. The upper bed of the Americus contains a persistent chert zone that extends southward from southwestern Greenwood County. The limestone is exposed in the creek bank just below the fork near the center of NW NW sec. 21, and in the creek bank in the southern part of the NE SW sec. 21, T. 22 S., R. 10 E. (see pl. 3), a short distance east of the Browning oil field, which is north of the area wherein it is chert-bearing. The upper limestone is used relatively little in structural geologic mapping, because it is separated by so small an interval from the lower limestone, which furnishes such excellent datum points for this part of the stratigraphic column.

The Hughes Creek shale, which overlies the Americus limestone, is composed of fossiliferous, limy, gray shale and limestone. A limestone (Thrall) above the middle of the Hughes Creek shale forms a prominent ledge and gives the member a three-fold division. The lower part of the Hughes Creek shale is concealed in most localities; where seen it is a light gray to light tan limy shale, increasing in lime content southward, and it contains a few thin beds of limestone that are abundantly fossiliferous. About 500 feet west of the S2 corner sec. 28, T. 22 S., R. 10 E., southeast of the Browning oil field, the Thrall limestone bed forms a small falls in the stream; the shale beds for several feet below it are so limy that here, where they are fairly freshly exposed, it is questionable whether they should be designated as limy shale or shaly limestone. The limy beds, which are 2 feet below the massive bed of the Thrall limestone, are ripple marked, layer upon layer, through a thickness of about a foot. The ripples have a relief of about one fourth of an inch; they average about 2 1/2 inches from crest to crest; they appear to be symmetrical in cross section, and they trend about north 38° east. There are slight differences in the trend of the ripples of the several beds, but the general direction is the same.

The next higher ledge-forming limestone, here named the Thrall limestone bed, from the Thrall post office in the Thrall oil field in western Greenwood County, persists from Elmdale, Kan., southward into Oklahoma, but in the southern part of Kansas it thickens greatly and appears to coalesce with adjacent beds and thus loses its individual identity. It is only 1 foot 4 inches thick near Elmdale on Cottonwood River, where it makes a very inconspicuous outcrop, but in western Greenwood County it forms a prominent rock ledge about 3 feet thick; in the Sallyards oil field, in T. 25 S., R. 8 E. (see column 5, pl. 2), it is about 9 feet thick but contains some limy shale; and in the exposure east of Beaumont, Kan., it is represented by 13 feet of massive limestone (see column 6, pl. 2). The Thrall limestone at the type locality, where it is 11 to 12 feet above the Americus limestone, is about 4 feet thick and is composed of light gray limestone that weathers cream-colored. The lowermost half foot and uppermost foot of the rock is thin-bedded and inclined to be shaly. The middle part of the member, 2 to 2 1/2 feet thick, occurs in two to three beds that commonly form a prominent ledge (see pl. 4-C). Its most distinguishing feature is a layer of blue-gray, dense chert nodules which occurs 4 to 6 inches below the top of the ledge-forming part of the member. In most exposures the limestone overlying the chert has been eroded away and the chert caps the ledge. The chert nodules are for the most part confined to a single stratigraphic horizon; they are separated by limestone; most of them are 4 to 5 inches in length and 1 to 3 1/2 inches in thickness; rarely single nodules or coalesced nodules reach a length of 10 to 11 inches. The limestone and the chert contain specimens of a large fusulinid. The chert becomes more abundant southward, and in the southern part of Cowley County the Thrall bed, together with the upper limestone of the Americus member, forms the chief chert-bearing part of the Foraker limestone.

Plate 4--A, The lower limestone of Americus member in the SE sec. 5, T. 24 S., R. 10 E., south of the Thrall oil field. B, Slab of fossiliferous Morrill limestone in sec. 18, T. 22 S., R. 10 E. C, Thrall limestone bed in the Thrall oil field; chert nodules shown at right of hammer head.

The Thrall limestone bed is exposed as a prominent ledge in the east bank of the principal creek that flows southwest through the SW sec. 32, T. 23 S., R. 10 E., a short distance east of the Thrall oil field. The chert bed and the ledge-forming part of the Thrall limestone are well exposed in the creek bed 500 to 1,000 feet southwest of the Phillips camp in the NW sec. 33, T. 23 S., R. 10 E. Most of the ledge-forming part of the limestone and the uppermost beds are exposed in the road cut on the east side of the draw just east of the north quarter corner of sec. 5, and the lower part is exposed on the west side of the gulch, near the center of the SW NE sec. 5, T. 24 S., R. 10 E.

The Thrall limestone forms conspicuous outcrops in parts of the Browning oil field in western Greenwood County and was therefore used in parts of the area for structural geologic mapping. Locally, it is divided by joints into massive slabs 1 1/2 feet thick and 10 to 15 feet broad. The slabs are conspicuous just south of the road in the slopes of a small gulch in the NW NW sec. 21, T. 22 S., R. 10 E.; this locality (see pl. 3) is 1 1/2 miles east of the Browning camp of the Sinclair Prairie Oil Co. The massive character of the bed is not persistent, however; it crops out as thin-bedded limestone in some localities in the Browning field. No chert was seen in the Thrall limestone in the Browning oil field.

The shale that separates the Thrall and Long Creek limestones and constitutes the upper part of the Hughes Creek shale is composed of limy shale that weathers gray to tan. It contains considerable calcareous material at all places where it was seen, and the content of lime increases southward. At many exposures in western Greenwood County, fusulinids weather out from this shale in such abundance that they coat the surface of the slopes with their wheatlike forms. The presence of fusulinids in abundance on such slopes is the most characteristic feature of the shale. In some localities the fossils are congregated in knotty concretions in very limy shale. The shale is exposed below the Long Creek limestone in the north bank of the creek, about 600 feet south of the northeast corner sec. 20, T. 22 S., R. 10 E., east of the Browning oil field.

The upper limestone of the Foraker formation has been identified near Elmdale, Kan., on the Cottonwood River, by Moore (personal communication) and Condra (1927, p. 85-86) as equivalent to the Long Creek limestone of Nebraska. It is composed of thick beds of friable light-buff limestone having a total thickness of about 8 feet near Elmdale, where it rarely forms conspicuous outcrops. The beds become harder southward, and the outcropping beds are thin and form a bench. In the Browning oil field, the lower third of the Long Creek limestone, which is 7 or more feet thick, is composed of relatively soft, chalky, cream-colored or slightly buff beds, each 8 to 12 inches thick; the upper two thirds is made up of thin white beds, each 1 1/2 to 2 inches thick. The limestone is exposed in part in the roadway less than a quarter of a mile east of the northwest corner sec. 21, T. 22 S., R. 10 E., and in the creek a few hundred feet north of this locality, which is a mile east of the Browning oil field. In southern Kansas this member is not so conspicuous as the Thrall limestone bed; there it commonly forms a slope, strewn with fragments of almost white limestone, above the rock ledge formed by the Thrall bed. The Long Creek limestone member contains no chert in the exposures examined.

Following is a section of the Foraker limestone, compiled from sections of parts of the formation measured in the following localities in and near the Thrall oil field: in the roadway near the southwest corner sec. 36, and the southeast corner sec. 35, T. 23 S., R. 9 E.; on the road between sec. 32, T. 23 S., R. 10 E., and sec. 5, T. 24 S., R. 10 E.; and near the center of the SW NE sec. 5, T. 24 S., R. 10 E.

| Section of the Foraker limestone in the Thrall oil field | Thickness | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feet | Inches | ||||

| Johnson shale | |||||

| Foraker limestone | |||||

| Long Creek limestone member: | |||||

| Limestone, light cream-gray, soft, thin-bedded except lowermost part; only sparingly fossiliferous | 7 | 6 | |||

| Shale, weathers light tan | 1 | 4 | |||

| Limestone, light gray, thin-bedded; contains a few fossils | 0 | 9 | |||

| Hughes Creek shale member: | |||||

| Shale, very limy; contains abundant specimens of a large fusulinid, that weather out of the shale and lie thickly strewn on the surface | 7 | 6 | |||

| Thrall limestone bed: | |||||

| Limestone, light cream-gray, thin-bedded; contains fusulinids | 1 | 0 | |||

| Limestone, light cream-gray, thick-bedded; contains a layer of blue-gray chert nodules, each 3 1/2 inches or less thick and 4 to 5 inches long; the limestone and chert contain abundant fusulinids | 2 | 5 | |||

| Shaly limestone, thin-bedded, fossiliferous | 0 | 5 | |||

| Shale, light tannish gray, weathered | 3 | 2 | |||

| Limestone, dark gray, fossiliferous, thin-bedded | 0 | 2 | |||

| Shale, dark gray, fissile; contains a few thin lenses of limestone | 1 | 5 | |||

| Limestone, dark gray, fossiliferous, thin-bedded | 0 | 10 | |||

| Shale, weathers tan, fossiliferous, in part limy | 6 | 0 | |||

| Americus limestone member: | |||||

| Upper limestone: | |||||

| Limestone, light gray, abundant fusulinids; weathers rough, like mortar | 0 | 7 | |||

| Limestone, dull gray, fossils and fossil fragments abundant, occurs in wavy surfaced thin beds | 0 | 10 | |||

| Limestone, light gray, thin-bedded and somewhat shaly; contains fusulinids | 1 | 6 | |||

| Shale, gray to dark gray; weathers tan; in part fissile | 2 | 9 | |||

| Lower limestone: | |||||

| Limestone, dark gray, dense, smooth upper surface; contains fusulinids and other fossils; breaks into large blocky slabs | 1 | 8 | |||

| Total-Foraker limestone | 39 | 10 | |||

| Admire group. | |||||

Johnson Shale--Overlying the Foraker limestone is a unit about 25 feet thick that is composed largely of beds of gray shale, some of which are very limy, and a few thin, inconspicuous beds of fossiliferous limestone. It persists across Kansas and is believed by Moore and Condra (1927, p. 86) to be equivalent to the Johnson shale of Nebraska (Moore and Condra identified this unit at Elmdale, Kan., as the Johnson shale).

Red Eagle Limestone--The interval of 20 feet succeeding the Johnson shale contains limestone in southern Kansas and northern Oklahoma, where it is known as the Red Eagle limestone. It consists of relatively thin-bedded gray limestone that for the most part contains but few fossils; the uppermost 3 to 4 feet is massive, rather coarse-grained, soft limestone that weathers to a deep buff color. The lower 3 to 5 feet of the Red Eagle limestone forms a jagged wall-like rock ledge and the uppermost few feet forms nodular buff chunks of rock in the slope above. Shrubs characteristically grow in greater abundance along the outcrops of the lower part of the Red Eagle limestone than on other units.

The Red Eagle limestone persists from the northern part of Oklahoma--its type locality (Heald, 1916, p. 24-25)--northward at least as far as the Cottonwood river valley; it is composed entirely of limestone as far north as the northwestern part of Elk county, where the middle part becomes somewhat shaly and splits the formation into two limestone members and an intervening shale. The lime content of the shale between the two limestone members decreases toward the northeast. The buff color and, in most localities, the massive bedding of the upper limestone member, persists northward to the Cottonwood River; this member characteristically crops out as a single bed of buff limestone that weathers in nodules about a foot thick. Near Elmdale, in the Cottonwood River valley, the upper member of the Red Eagle limestone has thinned to about a foot in thickness; it crops out there as small brownish-buff slabs not very conspicuous in the sodded slopes. The lower limestone member forms a conspicuous outcropping rock ledge in the river bluffs east of Elmdale, where it was noted and described by Prosser and Beede (1904, p. 2) as No. 6 in their section measured there. It maintains its characteristic features northward beyond the Cottonwood River valley.

The three members of the Red Eagle limestone were identified in Kansas by me as far northward as the Cottonwood River bluffs east of Elmdale. Moore and Condra (R. C. Moore, personal communication) have identified these beds at the Elmdale locality as being equivalent to the Glenrock limestone (the oldest), Bennett shale, and Howe limestone of northern Kansas and Nebraska. Both of the limestone members of the Red Eagle have been used extensively in detailed geologic mapping in the oil fields in the western part of Greenwood County. They form prominent ledges in the Thrall oil field. The Glenrock limestone member at the base is 3 1/2 feet thick; its outcrops form a bench strewn with thin white fragments of limestone. It is prominently exposed in the easternmost part of section 31, in section 32, and the western part of sec. 33, T. 23 S., R. 10 E. The Bennett shale member, just above the Glenrock, is not well exposed, but the Howe limestone member that overlies the Bennett forms two benches; the lower is composed of massive, light buff limestone; two feet above it white, fine-grained slabs of limestone form the upper bench. The massive bed of the Howe limestone is exposed a short distance east of the S1/4 corner of sec. 28, and the overlying slabby beds are exposed near the road in the SE NW sec. 33, T. 23 S., R. 10 E.

Near the Browning oil field the Glenrock limestone ledge in the south bank of the creek near some large trees in the southern part of the NE NE sec. 20, T. 22 S., R. 10 E., can be seen from the road along the north boundary of the section. The limestone is composed of light gray, thin beds that weather into plates only half an inch or so thick. The Bennett shale, 9 feet thick, forms sod-covered slopes in most localities. An exposure above the ledge of the Glenrock limestone in the slope south of the creek in the southern part of the NE NE sec. 20, reveals the lowermost 3 to 4 feet to be an abundantly fossiliferous weathered tan shale. Exposures elsewhere in the Browning field show the uppermost 2 feet of the shale to be tan and fossiliferous. In the Browning oil field the Howe limestone consists of a lower massive bed 3 feet 4 inches thick, a middle greenish shale 1 foot 2 inches thick, and an upper limestone 1 foot 9 inches thick that is composed of beds 3 to 5 inches thick and is light gray on fresh surfaces and ocherous yellow on weathered surfaces. The lowermost foot of the lower massive limestone forms the outcropping ledge in all exposures except in recently cut stream channels; it weathers into chunks about 9 inches thick that have a very rough surface on which there are sharp prongs up to 1 1/2 inches long. Such a surface is so characteristic that the bed was designated in the field notes as the "rough bed." The lowermost half foot of the ledge-forming bed is somewhat earthy and weathers ocherous yellow. Excellent exposures of the ledge-forming bed of the Howe limestone can be seen on both sides of the valley in the NE NE sec. 29, and in the SE sec. 20, T. 22 S., R. 10 E.; complete exposures can be seen in the stream banks just east, also north of the N2 corner sec. 29, and just west of the center of sec. 20, T. 22 S., R. 10 E.

Roca Shale--A unit 20 to 35 feet thick, composed of somewhat limy gray shale, maroon shale, and a persistent limestone, overlies the Red Eagle limestone. Its most distinguishing features are the maroon color of the lower part of the shale, and the limestone near the middle of the formation. The Roca shale persists from the Oklahoma-Kansas boundary northward to the Cottonwood River valley, and Moore (personal communication) states that it continues still farther northward into Nebraska where it has been named by Condra (1927, p. 86). The limestone near the middle of the Roca shale crops out in thin slabs that in many localities contain fossils in abundance. It persists from northern Oklahoma northward to the Cottonwood River. Although it forms a ledge in many localities, particularly in southern Kansas, in northern Greenwood County it makes only a slight shoulder strewn with limestone fragments about 10 to 15 feet below the ledge formed by the Burr limestone. Near Elmdale on the Cottonwood River the limestone is very inconspicuous, and is represented by only a little less than 2 feet of shaly, thin-bedded limestone.

Grenola Limestone--The Grenola limestone includes all beds between the Roca shale below and the Eskridge shale (as redefined) above. It embraces three ledge-forming limestones and the intervening shales: (1) At the base is a blocky limestone that forms a prominent ledge. (2) About 12 feet above it is a fairly thick limestone, which is the Neva limestone as named by Prosser at Neva station; it varies from a massive escarpment- forming rock, as shown near Neva and Elmdale, to a thin-bedded inconspicuous unit as revealed in the Browning oil field in Greenwood County; it contains some chert in many localities. (3) At the top is another massive limestone that weathers into a nodular ledge very similar in appearance to the limestone next below. The Grenola limestone was named by Condra and Busby (1933) from exposures near Grenola in southwestern Elk County, Kansas.

The three limestones that are mentioned above persist along the outcrop from northern Oklahoma to the Cottonwood River valley; each is composed of fossiliferous gray limestone that forms ledges in the slopes; each decreases in thickness northward, a feature common to most of the limestone units in this part of the stratigraphic column. The shale that separates the limestone beds becomes increasingly limy southward, and limestone predominates over shale near the southern boundary of the state. All members of the Grenola limestone are exposed in the bluffs north of the railroad track in the Grand Summit oil field near the Cowley County boundary, a few miles northeast of Grand Summit.

Burr limestone--The Burr limestone is the lowest bed in the Grenola limestone. The middle part of the member characteristically crops out as a massive bed that forms a narrow pavement of smooth-surfaced blocks about a foot or more thick; abundant specimens of a large species of Myalina lie on its upper surface in many localities. The member makes clean-cut outcrops as far north as the northern part of Greenwood County. The limestone has a total thickness of 6 1/2 feet, but only the middle part of it is exposed in most outcrops; its habit of forming blocky slabs persists from western Greenwood County southward into Oklahoma, but it is rarely exhibited north of Greenwood County; it forms a fairly conspicuous limestone-strewn terrace 12 to 15 feet below the escarpment of the Neva limestone about half a mile south of the highway along the bluffs southeast of Elmdale; it is No. 10 in Prosser and Beede's (1904, p. 2) section measured in the bluff east of Elmdale and was called lower Dunlap by these authors after Kirk (1896, p. 81), who included the main ledge-forming member of the Neva limestone as the upper limestone unit of the Dunlap. The Burr limestone is exposed north of the railroad in the Grand Summit oil field in northeastern Cowley County.

In the Thrall oil field, in western Greenwood County, the Burr limestone and limestone beds above and below it are partially exposed immediately south of the Thrall No. 51 oil well in the center of the west line NE SW sec. 28, T. 23 S., R. 10 E. (pl. 5). There a limestone bed in the Roca shale forms a shoulder strewn with limestone fragments (elsewhere in the vicinity it forms a low ledge composed of thin plates); the next higher limestone, which is the Burr, forms a low ledge, and the next higher limestone, which is the lower limestone of the Neva, crops out only a few feet south of the oil well. In the Browning oil field, in northwestern Greenwood County, the Burr limestone caps a narrow ridge that trends eastward through the northern part of the S2 NE sec. 20, T. 22 S., R. 10 E., and crops out in large slabs a foot or less thick, containing specimens of a Mylina that are from 2 to 3 inches long.

Salem Point shale--The strata between the Burr limestone below and the Neva limestone above comprise the Salem Point shale. This member forms gentle slopes that are sod-covered in most localities. At a few places where the Salem Point shale beds were seen, they consist largely of gray to drab shale, in part limy, and a few thin lenses of shaly limestone, with a total thickness of about 15 feet.

Neva limestone--The type locality of the Neva limestone, as long used in stratigraphic descriptions (Prosser, 1902, p. 709; Prosser, 1904, p. 2) of Kansas rocks, is near Neva station in the Cottonwood river valley; there the Neva limestone is a prominent ledge-forming rock 11 feet thick; it is light gray with a light-buff hue, weathers to a pitted, sharply rough surface, and contains many fossils. About 4 1/2 feet above the main ledge in this vicinity is a light-gray limestone a foot or less thick, separated from the main ledge by calcareous gray shale. Southward this upper thin limestone increases in thickness, becomes massively bedded, crops out with a slightly pitted, sharply rough surface, and closely resembles the main limestone of the type locality.

These two ledge-forming limestones--one 11 feet thick and the other 1 foot thick at Neva--are the two upper limestones of the Grenola limestone and comprise the Neva limestone as now classified by the Kansas Geological Survey. They form prominent outcrops 10 to 12 feet apart between Neva and localities in Cowley County. The upper unit maintains the massive character and crops out as a nodular, pitted, light-gray ledge that is more persistent than the ledge of the lower unit (the Neva limestone of old reports), which in some localities is thin bedded. Southward, in Cowley County, the shale between the two limestones becomes increasingly calcareous, finally joining the two limestones into one unit about 20 to 25 feet thick, which includes some additions of limestone beds above the upper unit and some below the lower unit; accordingly, the limestone beds appear to expand southward, both above and below. This relationship is shown on Plate 2. Although the early Kansas reports restricted the term Neva limestone to the main ledge-forming bed of the type locality, which is the lower one of the two just described, the geologic report on Cowley County (Bass, 1929, p. 55-56) placed both the limestones and the intervening shale described above in the Neva limestone. This definition for Cowley County is believed to correspond closely with the usage in northern Oklahoma (Heald, 1916, p. 23-24).

In the southern part of Kansas and in the northern part of Oklahoma, where the two limestones of the Neva limestone are merged into one thick limestone unit, the uppermost part of the merged limestone contains rock that is more massive and is inclined to be more readily soluble than that in the lower part, a fact that was commented upon by Heald (1916, p. 23-24). Because of the readily soluble nature of the upper part of the limestone, it forms rock outcrops in only a relatively few localities in the southern part of Kansas. Exposures in the bluffs north of the railroad track near the Cowley County boundary east of Grand Summit, where section No. 8 on Plate 2 was measured, reveal these beds as well as other parts of the Grenola limestone. There, the upper limestones that form the Neva are joined by easily soluble limestone beds that occupy the position of the shale of the region to the north. The upper limestone is massive, porous, and easily soluble; it forms a rock outcrop for only a few hundred feet--elsewhere it is covered with soil and sod. The lower of the two benches of the Neva limestone contains chert and forms a prominent ledge on the north bank of the creek, north of the railroad and a short, distance west of the Grand Summit oil field; it corresponds to the main ledge at Neva on the Cottonwood River.

In the Thrall oil field, in western Greenwood County, the lower limestone of the Neva forms a ledge of white slabs near the crest of the divide that, trends northeast-southwest through sec. 31, the SE SE sec. 30, and into sec. 29, T. 23 S., R. 10 E. The upper limestone of the Neva is exposed in the E2 sec. 29, T. 23 S., R. 10 E., near the crest of the divide in the northernmost part of the Thrall oil field, where it crops out as a massive nodular bed of light gray rock. It is better exposed on the north side of the draw in the SE SW sec. 21, T. 23 S., R. 10 E., half a mile north of the oil field. In the Browning oil field in northwestern Greenwood County the lower limestone of the Neva consists of a lower bed of limestone 8 inches thick that is fossiliferous in some localities, weathers brownish, and has irregularly shaped grooves and pits 1 to 1 1/2 inches deep on its upper surface, a middle bed of gray limy shale 2 feet thick, and an upper bed of light-gray limestone 1 foot thick that crops out in large slabs. The beds of this limestone are well exposed and form the rim of the gulch due north of the Theta Oil Co.'s camp in the NW sec. 17; they are well exposed, also, in the draw near the center of SW NW sec. 20, T. 22 S., R. 10 E.

In the Browning oil field the upper limestone of the Neva resembles the lower limestone of the type locality (Neva station) more closely than the next lower limestone, which is believed to be equivalent to the bed of the type locality. The upper limestone of the Neva crops out in the Browning oil field as light gray to white nodular masses that have a granular texture. Exposures in sec. 17, T. 22 S., R. 10 E., immediately north of and about half way between the Theta Oil Co.'s camp and the oil well derrick that stands farther north near the rim of the gulch, are typical. The same limestone is exposed in the creek bank near the southwest corner of the NE NE sec. 18, T. 22 S., R. 10 E., where it is 2 feet 9 inches thick; here the lower 2 feet of the bed is thin-bedded, light gray, and abundantly fossiliferous, and the upper 9 inches is very porous, pumaceous-like, light gray to cream-colored rock. Maroon and gray shale occur above the limestone here.

Eskridge Shale--The Eskridge shale consists of greenish-gray and dull maroon shale, in part limy, and a few thin beds of limestone. Only parts of it were seen in the localities shown on Plate 2. The Eskridge shale is partially exposed in the westernmost part of sec. 27, T. 23 S., R. 10 E., in the Thrall oil field, and in the creek banks in the NE sec. 18, T. 22 S., R. 10 E., in the Browning oil field. The Eskridge shale includes all beds between the Neva and Cottonwood limestones, but 12 to 15 feet of shale and limestone beds that were formerly placed in the lowermost part of the Eskridge shale have been transferred by the Kansas Geological Survey to the Neva limestone. Furthermore, the Cottonwood limestone pinches out in southernmost Kansas, in consequence of which the Eskridge and Florena shales form a continuous body called the Eskridge-Florena shale by the Kansas Geological Survey. The Eskridge-Florena shale includes all beds between the Neva limestone below and the Morrill limestone above. My work determined that the Cottonwood limestone ceases to be a recognizable limestone unit near Grand Summit in T. 31 S., R. 8 E., and from that place on southward into Oklahoma, the Eskridge and Florena shales merge in a shale unit that ranges between 35 and 40 feet thick. The upper third or so of this combined unit is very limy and contains an abundance of fossils.

Beattie Limestone--The Beattie limestone includes the Cottonwood limestone, Florena shale and Morrill limestone.