Prev Page--Method of Study || Next Page--Cross Sections

Description and Correlation of Subdivisions

In the following discussion of the general characteristics of the Upper Cambrian and Lower Ordovician subsurface rocks in Kansas, equivalent formations in Missouri that have already been studied and classified are used as type sections for comparison. In order to establish the identity of the stratigraphic zones that are correlated with the subdivisions of the type section, their limits are defined by contrasting the characteristics of each zone with those of the subjacent and superjacent beds. A columnar section (Fig. 2) summarizes the stratigraphic sequence, thickness, and general features of the Upper Cambrian and Lower Ordovician formations in Kansas.

Figure 2--Columnar section of Upper Cambrian and pre-St. Peter Lower Ordovician rocks in the subsurface of Kansas. An Acrobat PDF version of this figure is available.

In the central Ozark region of Missouri these beds, where fully developed, attain a maximum thickness of approximately 2,000 feet. In western Missouri the section thins to approximately 1,000 feet. In Kansas, the thickness of these rocks is controlled by differences in sedimentation and by pre-St. Peter and later intervals of erosion during which great thicknesses of these rocks were removed from structurally high areas. In southeastern Kansas the thickness ranges from 1,000 to 1,200 feet. Northward, in the vicinity of Kansas City, the section thins to approximately 500 feet. In Richardson County, Nebraska, only 200 feet of these beds are present, and still farther north all Upper Cambrian and Lower Ordovician beds are absent in a well drilled at Nehawka, Nebraska (Condra, 1939, p. 12).

In south-central Kansas, Upper Cambrian and Lower Ordovician beds, exclusive of the St. Peter, are little more than 900 feet thick. The few wells in north-central Kansas that penetrate the entire thickness of Paleozoic rocks indicate a rapid northward thinning of the beds to less than 300 feet in Ottawa County. This measurement does not include 114 feet, of quartzitic sand, probably of Pre-Cambrian age, at the bottom of one well. In the region of the Central Kansas uplift the thickness of these beds varies considerably from place to place as a result of local structural conditions. An average known thickness of 600 feet prevails in the west-central part of the state. In some areas that are structurally high, the beds are much thinner or locally absent. The thickness of Cambrian and Lower Ordovician beds in southwestern Kansas has not been determined owing to lack of sample information. However, the presence in this area of beds possibly equivalent to the Cotter dolomite, Powell dolomite, Smithville limestone, and perhaps younger beds suggests that the thickness of the sequence may increase considerably in that direction.

The Upper Cambrian and Lower Ordovician dolomitic sequence in Kansas here described is overlain by beds ranging in age from the Simpson group (Lower and Middle Ordovician) to the Pennsylvanian. Beds of the Simpson group immediately overlie this sequence throughout most of Kansas except in the structurally high areas of the Nemaha anticline, the Chautauqua arch, and the Central Kansas uplift. The Chattanooga shale and Mississippian rocks overlie the sequence of Upper Cambrian and Lower Ordovician rocks in the area of the Chautauqua arch in southeastern Kansas. Post-Mississippian removal of great thicknesses of the older beds from the crests of the Nemaha anticline and the Central Kansas uplift resulted in the deposition of Pennsylvanian sediments on the eroded surface of Upper Cambrian and Lower Ordovician rocks.

Upper Cambrian and Lower Ordovician rocks are within 500 feet of the surface in the southeastern part of the state. The depth to the top of these formations increases westward to more than 6,000 feet.

Upper Cambrian Rocks

The Upper Cambrian sequence in Kansas comprises the Lamotte sandstone, the Bonneterre dolomite, and the Potosi and Eminence dolomites. The Davis formation and Derby and Doe Run dolomites are exposed at the surface in southeastern Missouri but are absent from large areas in the subsurface of western Missouri (McQueen, 1931, pp. 126-127), and they seemingly are not present in Kansas. The Proctor dolomite, a non-cherty formation overlying the Eminence in Missouri, has not been recognized in Kansas.

Lamotte Sandstone

The Lamotte sandstone, which unconformably overlies much of the Pre-Cambrian surface, crops out in the St. Francois Mountain area of southeastern Missouri. There it consists of a brown to white, locally dolomitic sandstone. The sand grains are clear to frosted, and their shape is subangular to rounded. The base of the formation is conglomeratic, and in most places it is highly arkosic. The formation is finer grained in the middle and upper parts. The zone of transition into the overlying Bonneterre dolomite consists of alternating beds of sandstone and dolomite.

Lithology in Kansas--A basal Paleozoic sandstone which lies unconformably upon Pre-Cambrian granite and metamorphic rocks is widespread in Kansas. Because it is overlain by beds ranging in age from Bonneterre to Roubidoux, Koester (1935, p. 1417) points out that it is a transgressive deposit of considerable continuity and of varying age. In this report, only that part of the basal sand in Kansas that is unconformable above the Pre-Cambrian granites and schists and conformable below the Bonneterre dolomite is correlated with the Lamotte sandstone of Missouri.

The Lamotte sandstone found in the Kansas subsurface lithologically resembles the Lamotte sandstone of Missouri in coarseness of grain, poor sorting, and relative purity. The average diameter of the sand grains is 1.5 mm, but angular quartz fragments 2.0 to 3.0 mm in diameter are common in the samples, The large proportion of coarse sand grains may be due in part to loss of fine sand during drilling operations or during the washing of the cuttings. For the most part, the grains are rounded, frosted, or water polished, and minutely roughened and pitted. Clear, extremely angular grains, however, are abundant. Some of these seem to be the result of secondary quartz enlargement, as shown by quartz crystal faces and terminations.

Considerable arkosic material in the form of somewhat kaolinized pebbles of feldspar is present in the basal part of the formation. Pyrite in crystals and massive fragments is associated with the sand in many wells.

Distinguishing characteristics--The basal part of the Lamotte sandstone is arkosic, which makes it difficult to determine its contact with the underlying granite in some wells. Flakes and needle-like fragments of broken quartz in samples from the base of the sandstone may represent a quartzitic phase of the Lamotte or they may represent a Pre-Cambrian quartzite. Loss through drilling of the softer feldspar constituents of granite may result in the production of cuttings resembling arkosic sand because of the seeming abundance of quartz.

The gradational contact of the Lamotte sandstone with the overlying Bonneterre dolomite is exhibited by two characteristics. (1) The size of the sand grains in the Lamotte sandstone decreases upward gradually. As a result, there is little contrast between the finest sand at the top of the Lamotte and the coarsest sand at the base of the Bonneterre. (2) Coarser sand grains, similar to those in the Lamotte sandstone, are incorporated in clusters of fine glauconitic sand of the Bonneterre. The distinction between the two formations is based upon the introduction and gradual increase in amount of dolomite and. the introduction of a considerable amount of glauconite in the Bonneterre dolomite.

The use of drilling fluid that allows the admixture of more than a normal amount of extraneous material in the cuttings makes the separation of the Bonneterre dolomite and Lamotte sandstone difficult in many western Kansas wells. Bonneterre dolomite may be present in samples from the Lamotte sandstone, thus obscuring the relative purity of the sand. Moreover, glauconite from the overlying Bonneterre may contaminate the samples of the underlying sandstone.

Distribution and thickness--The distribution of the Lamotte sandstone and its relation to younger basal Paleozoic deposits are shown in Figure 3. The Lamotte sandstone occurs in eastern Kansas in a broad curving belt parallel to the Kansas-Missouri state boundary, and in a less well-defined area in western Kansas. It is absent from an extensive area in the central part of the state (Fig. 3), except for 80 feet of sand overlain by typical Bonneterre dolomite in a well in southern McPherson County (well 16). It is absent also from wells in Kearny and Gove counties and western Logan County.

Figure 3--Formations in contact with Pre-Cambrian surface in Kansas at the close of Cotter time. An Acrobat PDF version of this figure is available.

Two interpretations of Figure 3 are possible.

(1) The Lamotte sandstone may have been deposited over the entire state and subsequently removed from central Kansas in pre-Roubidoux, pre-Van Buren, pre-Eminence, or possibly pre-Bonneterre time as a result of local upwarp across the central part of the state. This original widespread distribution of Lamotte and Bonneterre deposits would account for their occurrence in the well in McPherson County (well 16). Although such an interpretation is possible, some features of the relationship between the Lamotte and Bonneterre in Kansas indicate that it is open to question. Pre-Eminence erosion would account for absence of Lamotte from the central pre-Roubidoux granite "high" but it would not account for absence of Lamotte from those areas on the flanks of the pre-Roubidoux "highs" in central and far western Kansas where Bonneterre dolomite is the basal Paleozoic deposit. Removal of Lamotte from those areas by pre-Bonneterre erosion is contradicted by the gradational contact of the Lamotte and Bonneterre in areas where both are present.

(2) That the absence of Lamotte from the central Kansas "high" is due to overlap is suggested by the distribution of the basal Paleozoic beds. The Lamotte sandstone seems to have been deposited in basin areas in eastern and west-central Kansas. This was followed by deposition of the Bonneterre dolomite without a break in sedimentation, as indicated by the gradational contact of the two beds. Bonneterre sediments spread beyond the margins of Lamotte deposition onto the exposed Pre-Cambrian rocks, probably covering the central part of the state (later being removed by pre-Roubidoux erosion). This interpretation is further substantiated by the identification of thin sections of upper Bonneterre on the flanks of the central "high" (Greenwood County, well 15).

The occurrence of Lamotte and Bonneterre deposits in the well in McPherson County (well 16) on the crest of the central "high," however, requires a special explanation if overlap is presumed. It is possible that a considerable thickness of Lamotte sandstone (80 feet is present in this well) could have been laid down in a local depression. It is probable that Bonneterre deposits were originally widely distributed throughout the state but were stripped by post-Bonneterre erosion from areas of greater elevation, as central Kansas is presumed to have been. If the area in McPherson County persisted as a local "low," a thick section of Bonneterre would remain.*

[* Note: It is easy to over-emphasize the meaning of the presence or absence of Lamotte, which is thin in most wells. There are only seven wells drilled through the Bonneterre in which the Bonneterre is not underlain by Lamotte. On the Pre-Cambrian surface the Lamotte would be absent on hills or divides in the same way that Pennsylvanian basal conglomerate is locally absent in areas of topographic elevation. Well 21 of cross section B-B' shows no Lamotte but wells 20 and 22 on either side do have Lamotte. The occurrence of an important Pre-Cambrian divide in central Kansas in any part of Late Cambrian time seems doubtful.

Pre-Van Buren and pre-Roubidoux erosion were active enough to bevel the older rocks on the flanks of the areas of uplift (so-called Pre-Cambrian "high") and would in any case have stripped off any rocks from the crests.

W. L.]

In eastern Kansas a maximum thickness of 130 feet of Lamotte sandstone was noted in eastern Crawford County. In western Kansas a maximum thickness of 70 feet was noted in northern Rooks County. Although the thickness of the Lamotte sandstone varies locally as a result of irregularities of the Pre-Cambrian surface upon which it was deposited, there is, in eastern Kansas, a general thinning of the Lamotte sandstone westward. In the central uplift area it is overlapped by the Bonneterre dolomite or grades into it.

Bonneterre Dolomite

The Bonneterre dolomite is exposed at the surface in the St. Francois Mountain region of southeastern Missouri and has been found by deep drilling throughout most of Missouri. It consists of a light to dark, finely crystalline dolomite with thin partings of light-green and brown shale. The insoluble residues, as determined by McQueen (1931, pp. 111-112), consist of angular, extremely fine-grained, well-indurated, glauconitic sandstone or siltstone with green and brown dolocastic shale in the upper part of the formation.

Lithology in Kansas--The Bonneterre dolomite in eastern Kansas is medium finely crystalline and commonly dark gray or brown. In northeastern and western Kansas the dolomite generally is buff to white and coarsely crystalline. In wells in Phillips, Rooks, and Decatur counties the dolomite is pink, red, and red brown, probably due to the inclusion of ferruginous material. Ulrich and Bain (1905, pp. 21-26) describe beds in the Bonneterre dolomite in Missouri that are pink or decidedly red.

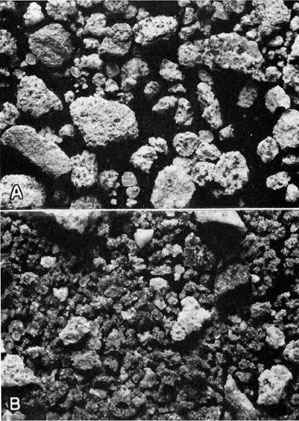

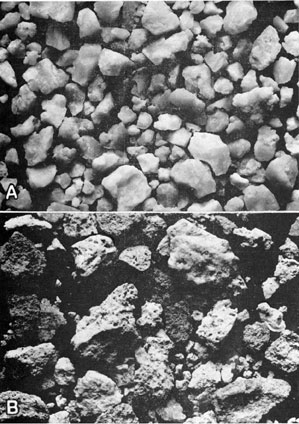

Residues from the Bonneterre dolomite of eastern Kansas grade upward from a coarse-grained, angular, relatively pure sand to an extremely fine silty sand. In the basal part of the formation the sand grains average 0.6 mm in diameter. The sand occurs both free and in loosely cemented clusters associated with large glauconite grains, some of which are 1.0 mm or more in diameter. Above this basal part is a zone of medium-fine bright angular sand in clusters associated with finer grains of glauconite (Pl. 1A). Upward, there is a gradual increase in the amount of brown porous silt in the residues, which gives the sand a spongy texture. The uppermost part of the Bonneterre is characterized by a dark-brown finely dolocastic spongy-appearing shale. Less glauconite is present in the shaly part of the residues.

Plate 1--Insoluble residues from the Bonneterre dolomite and the Eminence dolomite. A, Insoluble residue of the Bonneterre dolomite, consisting of loosely cemented clusters of medium fine glauconitic sand (x10). The sample is from the La Salle Oil Co. No. 1 Gobl well, SE cor. NW sec. 20, T. 28 S., R. 25 E., Crawford County, Kansas, from a depth of 1687-90 feet. B, Brown quartzose druse which may represent the Potosi dolomite at the contact of the Eminence dolomite with the Bonneterre dolomite (x10). The light-colored fragments are Bonneterre sand aggregates. The sample is from the No. 1 Clark well, sec. 13, T. 33 S., R. 21 E., Cherokee County, Kansas, from a depth of 1669-74 feet. An Acrobat PDF version of this figure is available.

Residues from wells in Shawnee, Douglas, Linn, and McPherson counties (wells 32, 30, 24, and 16) are composed of bright-green waxy shale with scattered dolocasts, associated with spongy masses of pyrite. These residues may represent an upper shaly phase of the Bonneterre dolomite or they may represent the base of the Eminence dolomite.

Residues from the Bonneterre dolomite in western Kansas are composed of sand grains that are subrounded, dull, polished, and somewhat pitted. Coarse bright very angular grains showing secondary quartz enlargement also are present. Although the sand is rather poorly sorted there is a general upward gradation from coarse rounded grains to fine more angular grains. The poor sorting may be due in part to contamination of samples from wells drilled with rotary tools. Coarse rounded fragments of feldspathic material occur in the basal part of the formation, particularly in those wells where Lamotte sandstone is absent. Associated with the sand is a considerable mass of large smooth rounded grains of glauconite, in some samples as much as 50 percent of the residue. Spongy and massive pyrite, flecks of brown spongy and green dolocastic shale, and scattered flakes of mica are present also.

The coarse rounded grains of sand and glauconite are conspicuous in the dolomite, particularly in the basal part. In some places, these rocks may be described more accurately as dolomitic glauconitic coarse sandstone.

The coarse grain size and feldspathic content of the sand, the heavy glauconite content, the scattered mica flakes, and the red color of the dolomite found in the Bonneterre deposits in western Kansas are similar to the red-brown glauconitic quartzite and sandstone of the Deadwood formation and Sawatch quartzite of the Rocky Mountain area.

Beds of Bonneterre age are absent over a broad region in the central third of the state, except for a remnant in southern McPherson County. The absence of the formation in this area makes it impossible to trace the Bonneterre dolomite across Kansas from east to west. Correlation must therefore be based upon similarities of the insoluble residues and upon the stratigraphic position of the Bonneterre dolomite with relation to beds that can be traced.

The similarities in the residues from these beds in eastern and western Kansas are: (1) prominence of sand as a constituent of the insoluble material; (2) gradual decrease upward in size of sand grains; (3) presence of much brown to green, commonly dolocastic shale, particularly in the upper part of the formation; and (4) presence of glauconite as a major constituent, which in Kansas seems to be limited to the Bonneterre deposits.

Dissimilarities in the residues of the Bonneterre in the separated areas lie in the size and degree of rounding of the sand grains. Those in the western part of the state are coarse, rounded, dull, polished, pitted, and somewhat feldspathic as contrasted with the very fine bright angular silty sand found in the eastern part of the state.

Stratigraphic relations--The Bonneterre dolomite is underlain by the Lamotte sandstone in the extreme eastern and western parts of the state. Toward the central uplift area (Fig. 3) the Lamotte sandstone is absent and the Bonneterre dolomite overlaps onto the Pre-Cambrian granite. Bonneterre dolomite also rests on granite along the crest of a locally high area in Kearny County and western Logan County.

The relationship of the Bonneterre dolomite to younger, more widely distributed beds is shown by means of cross sections in Figures 10 to 13. Beds ranging in age from Eminence to Roubidoux overlie the Bonneterre dolomite. Throughout most of eastern Kansas the Bonneterre dolomite is overlain by the Eminence dolomite. In a well in Richardson County, Nebraska (well 41), the Roubidoux rests on the Bonneterre dolomite.

In western Kansas, the Bonneterre dolomite is overlain by sandy Roubidoux dolomite, except in an area centering around Logan, Gove, and Trego counties, where it is overlain by cherty Eminence dolomite.

Distinguishing characteristics---In places where the Bonneterre dolomite is underlain by the Lamotte sandstone, the contact is gradational and differentiation is based on an increased percentage of dolomite, somewhat finer more angular sand, and the presence of glauconite in the samples of the Bonneterre dolomite.

Separation of the Bonneterre dolomite from the overlying Eminence dolomite and the Van Buren-Gasconade sequence is based upon the contact of the dark-colored dolomite of the Bonneterre with the light-colored dolomite of the higher beds, and the contact of the silty sand residue of the Bonneterre dolomite with the dominantly cherty residue of the overlying formations. The extremely fine brown silty sand of the upper part of the Bonneterre dolomite is easily distinguished from the rounded, well-sorted, secondarily enlarged, relatively coarse sand of the Gunter sandstone member of the Van Buren formation.

In central and western Kansas where the Bonneterre deposits are overlain by a sandy dolomite of Roubidoux age, the separation of these beds is difficult. The contact is marked by a change from the coarse rounded pitted sand residue characteristic of the Bonneterre dolomite in this area to a fine bright angular sand residue of the Roubidoux dolomite, and by the absence of glauconite from the Roubidoux dolomite. No distinct and consistent change in the dolomites is noted.

Distribution and thickness--The distribution and thickness of the Bonneterre dolomite in the subsurface of Kansas are shown by Figure 4, an isopachous map. Bonneterre dolomite is present in eastern and western Kansas but is absent from parts of central Kansas where no beds older than Roubidoux have been found.

Figure 4--Thickness of the Bonneterre dolomite in Kansas at the close of Early Ordovician time. An Acrobat PDF version of this figure is available.

The maximum thickness of Bonneterre in eastern Kansas is 198 feet, noted in a well in eastern Crawford County (well 13). The formation becomes thinner to the north. It is 90 feet thick in Shawnee and Douglas counties, Kansas, and 70 feet thick in Richardson County, Nebraska. The Bonneterre dolomite wedges out to the west against the central uplift area. Whether this wedging out is due to overlap on a high area over which Bonneterre sediments were not deposited or whether it was deposited over the area and later removed is problematical.

In western Kansas, a maximum thickness of 125 feet of Bonneterre dolomite is present in a well in southwestern Phillips County (well 48). Northward, thinning is indicated by the presence of only 96 feet of these beds in northern Phillips County (well 36) and 66 feet in Decatur County (well 37). Thinned sections of Bonneterre found in wells in Kearny County and western Logan County probably are reflections of a local area of considerable elevation at the beginning of Cambrian time. It is probable that the Bonneterre dolomite thickens to the south but lack of evidence prevents the determination of its distribution, thickness, or lithology in this area.

Potosi and Eminence Dolomites

In Missouri the Bonneterre dolomite is overlain by a section of cherty dolomite that includes, in ascending order, the Potosi dolomite and the Eminence dolomite. The noncherty Proctor dolomite overlies the Eminence. The bulk of the material found between the Bonneterre dolomite and the Gunter sandstone member of the Van Buren in Kansas probably correlates with the Eminence dolomite of Missouri. There is considerable question regarding the relationship between the Eminence and Proctor dolomites in the Ozark region. The Proctor, if present in Kansas, is included with the Eminence.

The Potosi dolomite crops out in the St. Francois Mountain area of southeastern Missouri where it consists of a dark-brown dolomite containing numerous quartz druses. McQueen (1931, pp. 114-115) found that these druses, mostly brown, are the principal constituent of the insoluble residues from the Potosi dolomite. This formation is missing from large areas in the subsurface of western Missouri (McQueen, 1931, p. 127), although it is reported to be 35 feet thick in Cass and Jackson counties (Clair, 1943, p. 34). It seems to be absent from most of the Kansas subsurface. Dark-brown coarsely crystalline dolomite 16 feet thick at the contact of the Eminence and Bonneterre dolomites in the No. 1 Clark well in Cherokee County (well 3) is associated with an insoluble residue of drusy brown chert and may be of Potosi age (Pl. 1 B).

The Eminence dolomite is exposed at the surface in southeastern Missouri where it is gray to almost white, coarsely crystalline, and massively bedded, and contains thin partings of green shale and thin nonpersistent lenses of sandstone. McQueen (1931, pp. 115-116) described the insoluble residues from the Eminence as containing a considerable percentage of white to light bluish-gray very vitreous and quartzose chert and fine dolocastic lace-like chert. Oölites coated with drusy quartz occur in some zones.

In Jackson and Cass counties of western Missouri, Clair (1943, p. 34) describes the Eminence in the subsurface as a "relatively non-cherty dolomite the insoluble content averaging less than 10 percent. . . . The chert is waxy gray quartzose, slightly oölitic and dolocastic. . . . The lower 100 feet of Eminence contains a green shale residue with some rounded sand."

Lithology in Kansas--The dolomite of the Eminence in Kansas is consistently buff to white and very coarsely crystalline. The light color and coarse texture are in sharp contrast to the gray or brown dolomite of the underlying Bonneterre but are nearly indistinguishable from the light-colored dolomites of the overlying Van Buren and Gasconade formations.

The predominant constituent of the insoluble residues from the Eminence dolomite in eastern Kansas is a blue to white semitranslucent chert with a vitreous glassy luster (Pl. 2A). Many fragments are incrusted with crystalline quartz. Drusy quartz, angular fragments of milky quartz, and dark-gray granular silica are common in the residues. Much lace-like dolocastic chert is associated with the quartzose chert. The dolocastic chert is characterized by the large size of the casts and thin chert walls. The cherty matrix is white and commonly soft and tripolitic. The combination of very fine casts and a soft tripolitic chert matrix causes some of the dolocastic chert to be porous and spongy rather than lacy. Traces of fine angular sand grains less than 0.1 mm in diameter occur sparingly in the samples. Flecks of bright-green smooth waxy shale probably represent thin shale partings. Pyrite occurs in considerable amount, commonly in spongy masses, but also in aggregates of fine crystals. Clusters of small smooth pyrite balls were noted in several wells. The occurrence of a considerable amount of arkosic material in the basal part of the Eminence dolomite in some wells in eastern Kansas is especially noteworthy. Rounded and somewhat weathered fragments of feldspar in Eminence residues were found in wells in Chautauqua, Labette, Cherokee, and Douglas counties. This implies pre-Eminence exposure of Pre-Cambrian rocks in areas not far distant.

Plate 2--Insoluble residues from the Eminence dolomite. A, White to blue semitranslucent vitreous to quartzose chert characteristic of the Eminence dolomite in eastern Kansas (x10). This sample is from the No. 1 Clark well, sec. 13, T. 33 S., R. 21 E., Cherokee County, Kansas, from a depth of 1569-75 feet. B, White to brown soft crumbly dolocastic chert characteristic of the Eminence dolomite in western Kansas (x10). This sample is from the Morgan, Flynn and Cobb No. 1 McMillen well, Cen. NW sec. 9, T. 13 S., R. 37 W., Logan County, Kansas, from a depth of 5350 feet. An Acrobat PDF version of this figure is available.

In western Kansas in wells drilled in Logan, Gove, and Trego counties, the cherty dolomite of the Eminence overlies sandy dolomite beds that are correlated with the Bonneterre dolomite and underlies beds that are correlated with the Roubidoux dolomite.

The Eminence dolomite is light buff and medium coarsely crystalline. The insoluble residues consist predominantly of soft brown to white fine to coarsely dolocastic chert (Pl. 2B). Flecks of bright-green shale and a considerable amount of spongy pyrite are associated with the chert in the residues.

Stratigraphic relations and distinguishing characteristics--In Kansas the Eminence dolomite is underlain by the Bonneterre dolomite from which it may be distinguished by characteristics of both the dolomite and the insoluble residue. In southeastern Kansas, where the Bonneterre dolomite is characteristically dark, the light color of the Eminence dolomite is in sharp contrast. Elsewhere in the state the differentiation must be based on the character of the insoluble residues. The Bonneterre residue is typically a glauconitic silty sand with little or no chert, whereas that of the Eminence dolomite is composed of quartzose and dolocastic chert. In those areas (Linn, Douglas, Shawnee, and McPherson counties) where the residue is composed of minute amounts of green shale, spongy pyrite, and sand grains, it is difficult to determine whether the beds represent the Eminence or an upper shaly phase of the Bonneterre.

The Van Buren-Gasconade sequence overlies the Eminence dolomite in eastern Kansas. The light-colored dolomite of the sequence is not consistently distinguishable from the Eminence. The quartz-encrusted cherts of the lower part of the Van Buren and Gasconade deposits are similar to the quartzose cherts of the Eminence. The well-defined Gunter sandstone member at the base of the Van Buren formation is the most reliable marker. In western Kansas the Eminence residues consist almost entirely of dolocastic chert, which affords a basis for distinguishing that formation easily from the overlying Roubidoux dolomite.

Distribution and thickness--The Eminence dolomite is present in eastern and western Kansas, as shown by Figure 5. It was observed to be 172 feet thick in a well in eastern Crawford County (well 13) and 175 feet thick in eastern Douglas County (well 30). This represents the maximum development of the Eminence dolomite in Kansas. The beds thin rapidly to the west and wedge out against the central uplift area in which no beds older than Roubidoux have been recognized. In western Kansas the thickness of the Eminence ranges from 55 to 87 feet in Logan, Gove, and Trego counties. The beds seemingly thin to the north and are absent from a well in Decatur County (well 37). The presence of Eminence dolomite in southwestern Kansas cannot be ascertained because well information is lacking. The absence of Eminence dolomite from the well in Kearny County (well 12) and slight thinning in western Logan County (well 23) reflect a local high area that is also reflected by the absence of the Lamotte sandstone and by the thinning of Bonneterre deposits in that region.

Figure 5--Thickness of the Eminence dolomite in Kansas. An Acrobat PDF version of this figure is available.

With the exception of dolomite and green shale 35 feet thick in a McPherson County well (well 16), no Eminence sediments are known throughout an extensive area in the central part of the state. Its absence in this area may be the result of nondeposition over the central uplift area, or of post-Eminence removal by erosion.

Lower Ordovician Rocks

The Lower Ordovician rocks in Kansas, exclusive of the St. Peter sandstone, or the Simpson sequence comprise the Van Buren-Gasconade sequence, the Roubidoux dolomite, and the Jefferson City-Cotter sequence.

Van Buren-Gasconade Sequence

The Eminence dolomite is overlain by a section of cherty dolomite which in Missouri includes the Van Buren formation, with the Gunter sandstone member at the base, and the Gasconade dolomite. These formations crop out in Missouri along the Osage and Niangua Rivers and in the deeper valleys of the Ozark Plateau. Deep drilling has shown their presence throughout the southern part of the state.

The base of the Van Buren-Gasconade sequence is marked by the persistent Gunter sandstone member of the Van Buren, which is the basal Ordovician deposit in this area. The Gunter sandstone of Kansas may be younger than the Gunter sandstone of Missouri. The thickness of the sandstone varies from place to place, ranging from 2 feet to at least 35 feet, as a result of the unconformable surface upon which it was deposited and also as a result of lateral intergradation with dolomite. At the outcrop the sandstone is generally rather thin-bedded and shows numerous ripple marks and much cross bedding. In Kansas the Gunter grades into the overlying dolomite of the formation.

At the outcrop, the Van Buren-Gasconade dolomitic sequence is light gray to nearly white and fine grained at the base. It becomes more massive and coarser grained in the upper part and has thin partings of green shale and occasional intercalated lenses of sandstone. A dense earthy "cotton rock" is common near the base of the Van Buren formation.

The Van Buren formation and Gasconade dolomite, which were distinguished from each other at the outcrop by paleontological evidence, have been differentiated in the subsurface by McQueen (1931, pp. 117-120) on the basis of insoluble residues, but it has not been possible to provide accurate and persistent criteria for correlating these beds individually in the subsurface of Kansas. Accordingly, the two formations are grouped as a unit.

Lithology of the Gunter sandstone member in Kansas--In Kansas, the Gunter sandstone member is a sandy dolomite rather than a pure sand. Insoluble material ranges.from less than 10 to more than 50 percent of the sample. The dolomite commonly is dark gray and more fine grained than that of either the underlying Eminence or the overlying Van Buren-Gasconade units,

In Kansas, as in Missouri, the sand of the Gunter seems to be sorted into two distinct sizes. Coarse grains range from 1.0 to 0.6 mm in diameter; fine grains range from 0.3 to 0.1 mm in diameter; there are few intermediate-sized grains. For the most part the grains are rounded, some being almost perfectly spherical. Even the smallest grains are subrounded. The surfaces are highly frosted or polished to a dull luster, and minutely pitted. Bright angular grains, both coarse and fine, are present in the sand in nearly every well as the result of secondary quartz enlargement.

The Gunter in Cherokee County (well 1) is represented by a residue composed of sand grains in a cherty matrix. The sand grains are of pure clear quartz; in the samples these are broken across the grains due to the impact in drilling. The chert matrix is white, dense, and somewhat quartzose. Free sand and sand grains in chert of the Gunter sandstone member are shown in Plate 5B.

In Sedgwick and Sumner counties the Gunter is the first sedimentary bed above the Pre-Cambrian surface and seemingly is the basal Paleozoic deposit (Fig. 3). In a Sedgwick County well (well 7) the Gunter is 53 feet thick and consists of very coarse angular quartz fragments and quartz sand grains, averaging 2.0 mm in diameter, immediately above the weathered surface of the granite. Approximately 15 feet above the granite the grains are smaller, averaging 1.0 mm in diameter. A considerable amount of bright-green fissile waxy shale is introduced 25 feet above the granite, in amount equal to 50 percent of the sample. These constituents may indicate a change in sedimentation during Gunter time or they may be merely shale caved from Simpson rocks higher in the well.

The presence of relatively unweathered feldspar at the base of the Gunter at the contact with the Bonneterre dolomite in the well in Wilson County (well 14) is of interest in connection with the occurrence of the Gunter as the oldest bed above Pre-Cambrian in wells to the west (wells 5 and 6 of cross section A-A').

In summary, the Gunter sandstone member in the Kansas subsurface resembles the Missouri equivalent in (1) the sorting of the sand grains into coarse and fine sizes, with few intermediate-size grains, (2) the high degree of rounding of the grains, (3) the polished and frosted surfaces of the sand grains, and (4) the considerable amount of secondary quartz enlargement.

Thickness of the Gunter sandstone member--The average thickness of the Gunter sandstone member in the subsurface of Kansas is 10 feet. This member probably is represented in the 46 feet of sandy, somewhat cherty dolomite found in the Holeman and Edwards No. 9 Pollman well (well 24) in Linn County, but the contact with the overlying Van Buren formation and Gasconade dolomite is indefinite. Twenty-two feet of Gunter sandstone was noted in a Wilson County well (well 14) resting on sandy Bonneterre dolomite. Increased thicknesses of Gunter were noted in wells in which the Gunter sandstone rested on Pre-Cambrian granite. Thus, wells in Sumner and Sedgwick counties (wells 6 and 7) penetrated Gunter sandstone 48 and 53 feet thick, respectively.

Lithology of the Van Buren-Gasconade sequence in Kansas--The dolomite of the Van Buren-Gasconade sequence as found in the subsurface of Kansas is white to light gray and is very coarsely crystalline, resembling that of the overlying Roubidoux dolomite. Zones of darker gray and more finely crystalline dolomite are interbedded with the light dolomite, but the darker zones seem to be local in distribution and are not traceable laterally for even short distances.

The amount of insoluble material from the Van Buren formation and Gasconade dolomite generally is large, averaging 25 percent of the sample. The chert types are similar to those that characterize these formations in Missouri. A white dense smooth somewhat porcelaneous chert having a dull to vitreous luster is more common in the lower half of the section but is not limited to that part (Pl. 3B). This may represent the equivalent of the Van Buren formation of Missouri. A chert that is very similar but more bluish translucent and with a vitreous to almost glassy luster (Pl. 3A) is more common in the upper half of the section. It may represent the equivalent of the Gasconade dolomite of Missouri.

Plate 3--Insoluble residues from the Van Buren-Gasconade sequence. A, Blue to tan translucent vitreous chert characteristic of the Van Buren-Gasconade sequence (x10). This sample is from the No. 1 Clark well, sec. 13, T. 33 S., R. 21 E., Cherokee County, Kansas, from a depth of 1467-72 feet. B, White dense smooth to rough chert characteristic of the Van Buren-Gasconade sequence (x10). This sample is from the No. 1 Clark well, sec. 13, T. 33 S., R. 21 E., Cherokee County, Kansas, from a depth of 1320-27 feet. An Acrobat PDF version of this figure is available.

There seem to be few distinctive chert zones within the Van Buren-Gasconade sequence that can be traced for distances of more than a few miles. Immediately above the Gunter sandstone member of the Van Buren the chert is white, dense, and porcelaneous. Many of the chert fragments are encrusted with quartz crystals and contain veinlets of crystalline quartz. Oölites occur in the chert in wells in Cherokee and Linn counties approximately 50 feet above the contact with the Gunter. The oölites are brown, large, and translucent in the Holeman and Edwards No. 9 Pollman well in Linn County (well 24). White oölites that are somewhat translucent and therefore very difficult to distinguish from the cherty matrix occur in the Glower No. 1 Forkner well in Cherokee County (well 2). The oölites seem to be broken across the diameter and are seen in section in the chert matrix.

A persistent zone of dolocastic chert in the lower 50 to 75 feet of the Van Buren formation in Missouri was described by McQueen (1931, p. 118). In Kansas, dolocastic chert occurs above the oölitic zone in wells in Labette and Linn counties. The casts are large and the walls thick. Dolocastic semiquartzose chert casts up to 0.4 mm in diameter lie immediately above the Gunter sandstone member of the Van Buren in a Crawford County well. The dolocastic chert is associated with much crystalline quartz and angular fragments of- quartz crystals. In Cherokee County a zone of tripolitic chert lies above the oölitic zone. A sandstone with poorly sorted, rounded, and frosted grains up to 0.8 mm in diameter and fine bright angular grains 0.1 mm in diameter, occupies the zone above the oölites in a Chautauqua County well (well 4). The tripolitic and dolocastic chert is overlain by a section of alternating beds of white dense porcelaneous chert and bluish semitranslucent chert. Fragments of dark-gray granular crystalline quartz are associated with the chert.

In Sedgwick and Sumner counties where the Van Buren-Gasconade sequence is the oldest unit above the Pre-Cambrian granite, the chert is white to bluish and semitranslucent. Oölitic, dolocastic, and tripolitic cherts are absent.

Stratigraphic relations and distinguishing characteristics--The Van Buren-Gasconade sequence rests unconformably upon each of the older formations. In its most typical development in eastern Kansas, this sequence rests on the Eminence dolomite. The absence of Eminence dolomite from the No. 3 Smith well in Wilson County (well 14) allows the Van Buren-Gasconade sequence to rest on upper beds of the Bonneterre dolomite. The cherty dolomite of the Van Buren-Gasconade sequence in Sedgwick and Sumner counties overlies the Pre-Cambrian rocks (wells 6 and 7).

In addition to characteristic rounding and sorting of grains, the Gunter sandstone member of the Van Buren may be distinguished from other sandstone of Late Cambrian and Early Ordovician age by its position below the more easily recognized Van Buren-Gasconade unit. In areas where they rest on the Eminence dolomite, cherts of the Van Buren and Gasconade are found to be less quartzose than those of the Eminence dolomite. In addition, the green shale common to the Eminence dolomite in some wells is absent from the Van Buren-Gasconade dolomitic sequence. In the Wilson County well (well 14) in which the Van Buren-Gasconade dolomitic sequence rests on Bonneterre dolomite, the separation is based on the change from the fine silty sand residue of the Bonneterre, to the coarser, rounded, or secondarily enlarged sand grains of the Gunter which is somewhat arkosic in this area.

Distribution and thickness--The distribution of the Van Buren-Gasconade sequence in Kansas is shown by Figure 6. The area of greatest thickness lies in the extreme southeastern corner of the state. One well in eastern Crawford County (well 13), two wells in Cherokee County (wells 1 and 2), and one well in Wilson County (well 14) contain more than 200 feet of these beds. In northeastern Kansas the Duffens No. 1 Stanley well in Douglas County (well 30) also has slightly more than 200 feet of the Van Buren-Gasconade deposits. To the north, the section thins to 90 feet, noted in the Forrester No. 1 Hummer well in Shawnee County (well 32), and it is absent from the Pawnee Royalty Company No. 1 Meyer well in Richardson County, Nebraska (well 41).

Figure 6--Thickness of the Van Buren-Gasconade sequence in Kansas. An Acrobat PDF version of this figure is available.

In the central part of the state the Van Buren-Gasconade unit seemingly wedges out by overlap or by beveling against a high area in which no beds older than Roubidoux have been encountered.

The formation seemingly was prevented from being deposited in western Kansas by the granitic "high" in the central part of the state or by pre-Roubidoux regional elevation and erosion of the western part of the state. No Van Buren or Gasconade deposits were found in wells studied in western Kansas, even in basin areas. Its presence or absence in the southwestern part of the state cannot be ascertained because sample data are lacking.

The western limit of the Van Buren-Gasconade sequence is indicated by its absence from wells in Pottawatomie and Chase counties and from wells west of McPherson County, Kansas.

Roubidoux Dolomite

The Roubidoux crops out over much of the central and northwestern parts of the Ozark Plateau, where it consists of massive beds of sandstone near the top and base and beds of cherty dolomite in the middle. According to Lee (1914, pp 21-22) the exposed dolomite at the base of the Roubidoux is lithologically similar to that of the underlying Gasconade dolomite, whereas the beds at the top contain cotton rock and closely resemble beds in the Jefferson City dolomite.

In the Kansas subsurface the limits of the Roubidoux dolomite arbitrarily are placed at the lower and upper limits of the more or less homogeneous section of sandy dolomite. The subsurface boundaries described here are, therefore, not necessarily the same as those at the surface. Cherty dolomites at the base, if present, are included in the Gasconade dolomite; if present at the top of the formation, they are included in the overlying Jefferson City and Cotter dolomites.

Lithology in Kansas--In Kansas, the Roubidoux dolomite consists of sandy dolomite and fine subangular sand, with cherty dolomites near the middle of the formation in some areas.

For the most part, the arenaceous character of the dolomite is not obvious in untreated samples. In both eastern and western Kansas, the Roubidoux dolomite is characteristically white and very coarsely crystalline. Coarse rhombs of dolomite are prominent near the base of the formation, becoming more finely crystalline upward.

In northeastern Kansas, brown medium coarsely crystalline dolomite occupies a zone averaging 40 feet thick near the contact with the Jefferson City and Cotter dolomites, as shown by wells in Shawnee, Jefferson, Douglas, Linn, and Bourbon counties. In the western part of the state, variations from the typical white coarsely crystalline dolomite were noted in several wells. The dolomite throughout the Roubidoux in the Osborne County well (well 26) is medium dark brown. A distinct pink color characterizes the dolomite in wells in Phillips and Rooks counties. (It should be remembered that the Bonneterre dolomite in these wells also is pink or red.) In Lane, Logan, and Gove counties the tan to buff medium to coarsely crystalline dolomite of the Roubidoux dolomite is indistinguishable from that of the overlying Jefferson City and Cotter dolomites.

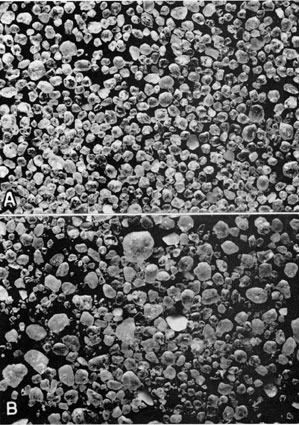

The insoluble residues of the Roubidoux dolomite range in amount from less than 5 percent to as much as 80 percent of the sample. The insoluble residues are strikingly alike over the entire state. In Kansas, as in Missouri, the principal constituent is clean white sand. In eastern Kansas the sand is fairly well sorted and the individual grains range in size from slightly more than 1.0 to less than 0.1 mm in diameter (Pl. 4A). In western Kansas the grains average somewhat larger and the sand commonly is very poorly sorted. Coarse sand grains caved from higher beds may be responsible, in part, for the wide range in grain size (Pl. 4B). In both eastern and western Kansas the larger grains are rounded, polished, or frosted and, in some cases, minutely pitted. Some of the larger grains, however, are bright and angular as the result of secondary quartz enlargement. Grains less than 0.2 mm in diameter are unfrosted and angular. Quartz crystal faces and striae on sand grains, indicative of secondary quartz enlargement, are characteristic of sand of the Roubidoux in Kansas as in Missouri. Doubly terminated quartz crystals and aggregates of crystalline quartz associated with the sand were noted in some residues.

Plate 4--Insoluble residues from the Roubidoux dolomite. A, Clear fairly well-sorted bright angular sand characteristic of the Roubidoux dolomite in eastern Kansas (x10). This sample is from the No. 1 Clark well in sec. 13, T. 33 S., R. 21 E., Cherokee County, Kansas, from a depth of 1262-68 feet. B, Coarser very poorly sorted sand characteristic of the Roubidoux dolomite in western Kansas (x10). This sample is from the Texas Co. No. 13-A Bemis well in the SE NW NE sec. 28, T. 11 S., R. 17 W., Ellis County, Kansas, a rotary-drilled well, from a depth of 3702-25 feet. An Acrobat PDF version of this figure is available.

In several wells in southeastern Kansas, the Roubidoux is composed of two sand or sandy dolomite members separated by a bed of cherty dolomite near the middle of the formation. In wells where the cherty zone is absent the Roubidoux formation is recognized by increasing percentages of sand in the residues at two distinct zones within the formation.

The chert of the middle zone closely resembles some of that found in the underlying Gasconade dolomite. White dense to bluish translucent chert amounts to as much as 75 percent of some samples. Veinlets of crystalline quartz cut through some of the fragments. Large brown translucent glassy oölites which probably resulted from the replacement of sand grains by secondary silica are common in the chert. Such chert has been found characteristic of the Roubidoux formation in Missouri (McQueen, 1931, p. 121).

Dark-brown and white banded oölites in a matrix of light-brown quartzose chert are associated with the sand in many residues at the contact of the Roubidoux with the Jefferson City-Cotter dolomites in wells in both eastern and western Kansas. Flecks of bright-green shale, in some cases dolocastic, and spongy fragments of pyrite commonly are associated with the sand.

The presence of chert beds in the Roubidoux formation in western Kansas is obscured by chert caved from beds higher in the well. The admixture of sand from higher beds within the Roubidoux formation lessens the contrast in the percentages of sand residues and makes the determination of distinct sandy-beds difficult.

Stratigraphic relations and distinguishing characteristics--The Roubidoux dolomite overlaps progressively older beds as it is traced to the central part of the state, where it immediately overlies Pre-Cambrian rocks. This relationship is illustrated by Figure 7 which shows the pre-Roubidoux surface and by the cross sections (Figs. 10-13).

Figure 7--Pre-Roubidoux paleogeologic map Kansas. An Acrobat PDF version of this figure is available.

Sand of the Roubidoux dolomite overlies the Van Buren-Gasconade sequence in eastern and south-central Kansas. Although the dolomites of the two formations are similar, the insoluble residues show a distinct and sharp contrast between the bluish cherts of the Gasconade dolomite and the fine angular sand of the Roubidoux dolomite.

The Roubidoux dolomite was not found in contact with the Eminence dolomite in wells studied in eastern Kansas. The cherty dolomite underlying the Roubidoux dolomite in some western Kansas wells is tentatively correlated with the Eminence dolomite of Missouri. The formational boundary is placed at the contact of the dolocastic chert of the Eminence with the sand residue of the Roubidoux dolomite.

In eastern Kansas where the Roubidoux dolomite is in contact with the Bonneterre dolomite, the base of the formation is placed at the contact of the dark-brown dolomite and fine silty sand residue of the Bonneterre dolomite with the white coarsely crystalline dolomite and somewhat coarser angular sand of the Roubidoux. The contact also is marked by a heavy concentration of pyrite in some wells.

In western Kansas the separation is more difficult because the typical fine silty sand and dolocastic shale is absent from the Bonneterre dolomite, and the dolomites of the two formations are indistinguishable. The criteria found to be most reliable for the establishment of the contact are as follows. (1) The Roubidoux sand is fine (averaging 0.1 mm in diameter, unfrosted, angular, and enlarged, whereas that of the Bonneterre dolomite is much coarser and the grains are rounded, minutely pitted, and roughened. (2) Glauconite, which is common in Bonneterre deposits, is absent in the Roubidoux. (3) A considerable amount of pyrite is associated with Bonneterre residues but occurs sparingly in the Roubidoux dolomite. A heavy concentration of pyrite is common at the contact of the two formations.

The Roubidoux dolomite, including the basal sand, is underlain by an arkosic quartzite or quartzitic sand in wells drilled in Ottawa and Ellsworth counties (wells 26 and 18). This quartzite may represent a thick deposit of "granite wash" that was formed by the weathering of the granite surface during Cambrian time or it may be a deposit of Pre-Cambrian quartzite. It may be granite that resembles a quartzitic sand in samples as a result of loss of the relatively soft feldspathic constituents which were drilled to fine rock flour and were washed from the sample leaving the relatively hard quartz elements intact. It is difficult to determine the formational boundary between the basal sand of the Roubidoux and the quartzite, but increasing amounts of arkosic material and the extreme angularity of the quartz fragments in the quartzite serve to distinguish it from the Roubidoux.

In one well in each of Barton and Chase counties (wells 19 and 25) the sandy dolomite of the Roubidoux rested directly on Pre-Cambrian granite with no basal sand intervening. Probably these areas were topographically high at the beginning of Roubidoux deposition.

The Roubidoux dolomite is overlain by the Jefferson City-Cotter sequence throughout Kansas, except for local areas in the northern part of the state where the sequence was removed by post-Cotter erosion (Fig. 8). The features of the Roubidoux dolomite that serve to separate it from the overlying Jefferson City-Cotter sequence are as follows. (1) The insoluble residues from the Roubidoux dolomite are predominantly sandy whereas those of the Jefferson City and Cotter dolomites consist of varied cherts and dolomites; impersistent sand occurs in the Jefferson City dolomites as discontinuous lenses only a few feet thick. (2) The change from the sandy Roubidoux section to the cherty Jefferson City-Cotter sequence is accompanied by a slight change in the character of the dolomite. The dolomite of the Roubidoux in most areas is white and very coarsely crystalline, with little variation throughout the section, whereas the dolomites of the Jefferson City and Cotter are varied both in texture and in color.

Figure 8--Thickness of the Roubidoux dolomite in Kansas at the close of Cotter time. An Acrobat PDF version of this figure is available.

The Roubidoux dolomite is the oldest formation of the Upper Cambrian and Lower Ordovician strata that extends uninterruptedly across the state from east to west. The continuity of the sandstone of the Roubidoux dolomite throughout the state has helped in the correlation of the older formations that are not so widely distributed.

Distribution and thickness--The distribution and thickness of the Roubidoux dolomite in Kansas are shown in Figure 8. A line extending from northern Leavenworth County to western Logan County roughly represents the northern limit of the Jefferson City-Cotter sequence. North of this line the Roubidoux dolomite was exposed and thinned by post-St. Peter erosion and in places it was entirely removed. This beveling is reflected by the absence of the Roubidoux dolomite from the Turner No. 1 Umschied well in Pottawatomie County (well 34). It also is indicated by the removal of all but 22 feet of the Roubidoux dolomite at the Phillips Petroleum Company No. 1 Vernon well in Decatur County (well 37). A normal section more than 200 feet thick is found in near-by wells.

Over a large area in the southeastern part of the state the thickness of the Roubidoux dolomite is relatively constant within the limits of 150 to 200 feet. An interesting exception is the Burge, Trott, et. al. No. 1 Breitkreutz well in Greenwood County (well 15) in which 72 feet of sandy Roubidoux dolomite rests on the dark-brown dolomite associated with the silty, sandy, and glauconitic residue typical of the Bonneterre dolomite. The absence of approximately 100 feet of lower beds of the Roubidoux as well as the Gasconade and Eminence dolomites is believed to indicate a locally high area at that place at the beginning of Roubidoux deposition.

In west-central Kansas the relatively thin section of Roubidoux (between 100 and 150 feet thick) underlain by Pre-Cambrian rocks indicates a high area on the pre-Roubidoux surface. In the central part of the state a thickness of Roubidoux greater than 200 feet indicates a pre-Roubidoux shallow basin in an area extending from southern McPherson County to central Sedgwick County between the "high" in west-central Kansas and the "high" shown by the well in Greenwood County.

The increase in thickness of the Roubidoux dolomite west of the high area in central Kansas indicates a basin filled by the Roubidoux sediments. The maximum thickness noted was 350 feet of sandstone of the Roubidoux dolomite in the Alma-McNeeley No. 1 Watchorn well (well 22) in Logan County. Approximately 30 miles west of this well, however, the Roubidoux dolomite thins to 235 feet in the Morgan-Flynn Cobb No. 1 McMillen well in Logan County (well 23). The Roubidoux is thinner also in the Stanolind Oil and Gas Company No. 1 Judd well in Kearny County (well 12). It is believed that this thinning is due to a local relatively high area that extended in a north-south direction through western Logan County and Kearny County at the beginning of Roubidoux deposition.

Jefferson City-Cotter Sequence

The Roubidoux dolomite in Kansas is overlain by beds correlated with the Jefferson City and Cotter dolomites of Missouri. These beds are separated at the outcrop and have been differentiated in the subsurface by characteristics of their insoluble residues (McQueen, 1931, pp. 121-124). Although a persistent sand zone that may represent the base of the Cotter dolomite has been correlated in several wells in southeastern Kansas, the lack of sufficient well control makes unreliable an attempt to differentiate these formations in the subsurface of western Kansas.

The Jefferson City and Cotter dolomites crop out in a broad belt encircling the structural center of the Ozark region. The dolomite of these formations at the outcrop is chiefly of two kinds: a fine-grained argillaceous earthy-textured variety and a more massive dolomite with a hackly surface. Intercalated commonly thin beds of chert, lenses of sandstone, and green shale partings are contained in the dolomite. The Jefferson City and Cotter dolomites are reported by McQueen (quoted by Lee, 1943, p. 20) to be 210 feet thick in Jackson County, western Missouri.

Lithology in Kansas--The dolomites of the Jefferson City-Cotter sequence in the subsurface of Kansas are variable in character. Beds that are only a few feet thick may differ greatly from those above and below both in color and in texture. The lithological character changes rapidly in a lateral direction, also. This lateral and vertical variability is a characteristic that serves to distinguish the dolomite of the Jefferson City-Cotter sequence from those of lower formations of Late Cambrian and Early Ordovician age.

In Kansas, a white to gray, dense, somewhat argillaceous soft dolomite, which probably is the equivalent of the "cotton rock" of Missouri geologists, is the most common type of dolomite in the Jefferson City-Cotter sequence. A light-tan medium coarsely crystalline dolomite is also very common. Brown dolomite occurs in the lower part of the sequence above the contact with the Roubidoux dolomite in most wells. It is commonly very dark and very coarsely crystalline. However, light-brown, gray-brown, or buff fine-grained dolomites occur in this zone in some areas.

The dolomite of the Jefferson City-Cotter sequence in Kansas contains a considerable amount of insoluble material of which cherts are the chief constituent. These cherts are characterized by their great variety. White dense and bluish translucent or brown cherts are the most common types. The white chert is dense with a smooth, porcelaneous surface and a vitreous luster. Veinlets and encrustations of crystalline quartz may give the chert fragments a quartzose appearance. The translucent chert is bluish to opalescent with a glassy, resinous, or paraffin-like luster. In some areas, the translucent chert may grade into a quartzose chert that resembles milky quartz. Much of this chert contains oölites that commonly are white or translucent, but some are brown. Both of these types of chert are found in all parts of the Jefferson City-Cotter strata and may be associated with any of the other types of chert common to the formation.

Quartzose and vitreous brown cherts are abundant in the lower part of the formation, usually associated with the brown dolomites. Some brown chert occurs in fine drusy clusters resembling brown sugar. Large brown oölites up to 0.8 mm in diameter, for the most part darker than the cherty matrix, are common in the brown cherts. Some of the oölites are opaque and others consist of alternating bands of opaque and translucent brown chert, or brown and white chert. Brown oölites that are free in the sample commonly are coated with a drusy quartz. McQueen (1931, p. 122) has found these brown oölites characteristic of the Cotter dolomite in Missouri, but in Kansas they are most common near the contact with the Roubidoux dolomite,

White oölitic chert may occupy the same stratigraphic position as brown oölitic chert in near-by wells and is thought to be a variant of the brown oölitic chert.

The presence of brown oölites in samples is used by many midcontinent geologists as a guide in identifying the top of the "Siliceous lime" because brown oölites seem to be more common in Upper Cambrian and Lower Ordovician strata than in younger formations. This criterion is unreliable because (1) in Kansas brown oölites are abundant in the lower part of the Jefferson City-Cotter sequence but not in the upper part, and (2) the Jefferson City-Cotter beds have been removed from large areas in Kansas.

Brown dense chert mottled with white chert was noted in many wells in southeastern and south-central Kansas. This type of chert was noted in samples from wells in Kansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma by McQueen (1931, p. 123) who assigns it to the lower part of the Cotter dolomite.

Dolocastic chert occurs in the insoluble residue of samples from all parts of the Jefferson City-Cotter sequence but is particularly abundant in the middle part of the sequence above the brown chert. It is associated with white dense and bluish translucent chert. A small amount of the chert is coarsely dolocastic and lacy. The greater part, however, consists of soft tripolitic chert matrix, with fine dolocasts that give the chert a spongy texture. Scattered large dolocasts occur in a white dense chert with a rough hackly surface.

A soft lusterless white finely porous tripolitic chert is found throughout the Jefferson City-Cotter sequence. McQueen (1931, p. 121) found it near the contact with the Roubidoux. Such chert is particularly abundant in wells in central and western Kansas but is not persistent laterally and may not be found in offset wells.

A small amount of chert with included sand grains, similar to chert found in the Roubidoux dolomite, is present in residues of the Jefferson City and Cotter dolomites. The association of oölites with the sand grains and the glassy centers of some oölites suggest that some of the white and bluish oölitic chert may be the result of replacement of the sand grains by secondary silica. The most common types of chert found in the Jefferson City-Cotter unit in Kansas wells are shown in Plate 5A.

Plate 5--Insoluble residues from the Jefferson City-Cotter sequence and Gunter sandstone member of the Van Buren formation. A, Assemblage of cherts from the Jefferson City-Cotter sequence showing (a) soft white lusterless tripolitic chert; (b) brown quartzose chert; (c) white vitreous chert; (d) brown and white oölites in chert; and (e) free chert (x10). This sample is from the Texas Co. No. 13-A Bemis well in SE NW NE sec. 28, T. 11 S., R. 17 W., Ellis County, Kansas (a rotary drilled well), from a depth of 3542-57 feet. B, Well-rounded highly polished sand grains sorted into distinct coarse and fine sizes and sand grains in chert characteristic of the Gunter sandstone member of the Van Buren formation (x10). This sample is from the No. 1 Clark well, sec. 13, T. 33 S., R. 21 E., Cherokee County, Kansas, from a depth of 1529-36 feet. An Acrobat PDF version of this figure is available.

Thin beds of sand or dolomitic sandstone occur in all parts of the Jefferson City-Cotter unit in Kansas but particularly near the contact with the underlying Roubidoux dolomite. For the most part, they are poorly sorted and rather fine grained. Most of the larger grains are rounded and frosted, whereas the finer grains are bright and angular. Secondary quartz enlargement is common.

Pyrite, in finely porous spongy masses and aggregates of fine crystals, occurs throughout the unit. Flecks of bright-green shale were noted in the upper part of the unit.

A persistent bed of sandstone- with a characteristic texture was traced over a considerable area in southeastern and south-central Kansas. It may represent the sandstone at the base of the Cotter dolomite which, in Missouri, serves to separate the Jefferson City and Cotter dolomites. The grains are well sorted and fine, averaging 0.2 mm in diameter, and are bright and angular. They occur both free and in loosely cemented clusters. The sand bed is approximately 10 feet thick in southeastern Kansas. It reaches its maximum development in Kansas in Cowley and Sumner counties, where it is 30 feet thick. In Reno and McPherson counties this sand probably is the uppermost zone of the Jefferson City-Cotter sequence. Westward it has been removed by post-Ordovician erosion.

Few wells in southwestern Kansas penetrate Upper Cambrian and Lower Ordovician beds more than a few feet. The few samples available consist of a fine angular sand and sandy dolomite which may be either the sand at the base of the Cotter dolomite or a sand higher in the section.

Stratigraphic relations and distinguishing characteristics--The Jefferson City-Cotter sequence in Kansas overlies the Roubidoux dolomite and is overlain unconformably by beds ranging in age from the St. Peter sandstone at the top of the Lower Ordovician to Pennsylvanian. The great variety of the cherts and dolomites offers considerable contrast to the white, coarsely crystalline, sandy, and comparatively noncherty dolomite of the Roubidoux.

Distribution and thickness--The distribution and thickness of the Jefferson City-Cotter sequence in Kansas are shown in Figure 9. A maximum thickness of 667 feet of these beds is found in Cowley County. Thicknesses of 350 to 400 feet prevail in the southernmost part of the state. Thinning is rapid to the north. In Douglas County the beds are 106 to 135 feet thick. They are absent entirely from wells in Jefferson County and farther north. In north-central Kansas the beds have thinned to approximately 122 feet in Ottawa County (well 26) and are absent from the one well studied in Osborne County (well 35). In western Kansas, the Jefferson City-Cotter sequence is known to be 382 feet thick in a well in Pawnee County (well 11). The unit is present in wells to the south and west but because the base of the unit has not been reached in the wells available for study, the maximum thickness in this region is unknown. Northward, the beds have thinned to only slightly more than 200 feet in a well in Trego County and are absent from wells in Rooks, Decatur, and Logan counties.

Figure 9--Thickness of the Jefferson City-Cotter sequence in Kansas. An Acrobat PDF version of this figure is available.

Prev Page--Method of Study || Next Page--Cross Sections

Kansas Geological Survey, Geology

Placed on web Jan. 22, 2010; originally published June 1948.

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

The URL for this page is http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/Bulletins/72/04_subd.html