Prev Page--From Haworth to Moore || Next Page--Post-World War II

8. R. C. Moore and the Survey of the 1930s and the 1940s

In the more than 100-year history of the Kansas Geological Survey, perhaps no name has been so widely known or so closely associated with the Survey as Raymond Cecil Moore. His was a remarkable career, based not only on 57 years at the Survey and the University of Kansas, but on the energy represented by vast scientific accomplishment. If there was a scientific office to be held, he held it. If there was a journal to be edited, he edited it. If there was a scientific idea to be argued, he argued it, and was nearly always remembered in the process.

Moore was, above all else, a scientific presence. William W. Hambleton, who directed the Survey from 1970 to 1986 and studied under Moore at KU, provided a visual description.

"Ray Moore was a man of medium height, stocky, wore glasses and always seemed rumpled. His complexion was tinged with red, especially around the nose. In earlier days, he characteristically smoked a pipe, but later consumed uncounted cartons of Pall Malls which stained his index finger yellow. A kind of sly smile always lingered about his mouth, suggesting amusement or the contemplation that his next question to you might be unusually interesting. He was a person of great appetite--for food, drink, work, play, generosity and appreciation. He possessed a large ego or, perhaps more appropriately, was comfortable in his knowledge of his own worth. His gait was sturdy, suggesting a certain inevitability about reaching a destination. He drove an automobile, not as a mode of transportation, but as an instrument of retribution." (Hambleton, 1974, "Raymond C. Moore Memorial," Moore Collection, KU Archives, p. 7)

Moore was fluent in at least six languages, part of which was due to his early work in classical languages at Denison University, work done before he changed his major to geology. He was a member of a relay team as an undergraduate; his athletic skills came in handy later in the field in geology. He played the piano. He was adroit at the game of bridge. And he drew. Moore used his sketching skills extensively in geology, perhaps figuring that the best way to know an outcrop was to draw it, although he often drew over photos to show a contact or disconformity or to make some other scientific point. His 1932 line-drawing of the surface features of Kansas is still regularly reprinted and given away by the hundreds. Yet he applied his artistic skills beyond geology, painting portraits and sketches of friends and other noted figures at KU.

R.C. Moore's depection of a Pennsylvanian coal swamp.

Cyclic sedimentation

But Moore's best-known accomplishments came in geology and can be grouped into four major areas: development of the concept of cyclothems; work in invertebrate paleontology; presence in scientific circles; and administration at the Survey and the KU department of geology. Probably the foremost geologic concept associated with Moore, and the one which engendered the most vociferous debate, was the idea of cyclic sedimentation. Cycles were recognized in geology long before Moore began discussing cyclic sedimentation in the 1930s. Moreover, Moore was not the first to recognize that natural cycles must have been partially responsible for the regular nature of the deposition of the limestones and shales in the midcontinent or even eastern Kansas. Papers on the subject appeared as early as 1912 (Udden, 1912). Detailed discussion began in the early 1930s (see, for example, Weller, 1930; Wanless and Weller, 1932; and Elias, 1934) and has continued into the present (for 1960s thinking on cyclothems, see Merriam, 1963, 1964. For a discussion of the development of the concept of cyclothems, see Heckel, 1984). Still, Moore was among those most strongly identified with the notion of cyclic sedimentation, with seas that deposited gray shales where they were shallow, limestones where they were deeper, and black shales where they were of intermediate depth, with occasional layers of coal and sandstone depending on the circumstances of deposition. As those seas advanced and retreated, they repeated those limestone/shale sequences over and over, with occasional layers of coal and sandstone, forming regular and generally predictable geology.

Moore was in a good location to study and discuss cyclothems. Regular deposition of alternating shale and limestone is common throughout the Pennsylvanian and Permian systems of eastern Kansas. Today it is spectacularly exposed in road cuts opened up by highway construction, though it was certainly apparent in the logs and sections studied by early geologists. Moore's background in invertebrate paleontology and knowledge of stratigraphy related to oil production from Pennsylvanian formations aided his study of those limestones and shales, and his ideas about their origin. Moore determined that the basic cyclothem was composed of four limestones--he called them lower, middle, upper, and super limestones--deposited by transgressive and regressive seas, seas that rose to cover the landscape, then receded again (Moore, 1931). He said the black shale formed in shallow water. Later Moore described what he termed an "ideal cyclothem," a series of rocks composed of sandstone, shale, underclay, coal, shale, limestone, shale, limestone, shale, limestone, and shale (Moore, 1936). This, said Moore, was the order in which the changing sea levels had deposited rocks. Wherever those units were not present in that precise order, it was because they had not been developed locally or had subsequently been eroded away. But ideally, they should be present in that order. Moore also developed the notion of megacylothems: a complex sequence of related cyclothems that can be lumped together (Moore, 1936).

In short, Moore was attempting to develop a standard model of Pennsylvanian and Permian deposition, against which he could measure what he saw in the field. That is, Moore developed an ideal for the way the world should look; where it looked different, he then explained that difference in terms of unusual circumstances in each location. Because of their sweeping impact on ideas about the geologic history of the midcontinent, and because those views also held some import to people who were searching for oil, Moore's pronouncements about cyclic deposition obviously stirred up controversy. There were arguments about where cyclothems began and ended--did they start or end with a sandstone? There were arguments about the mechanisms for sea-level change. There were arguments about the number of cyclothems and megacyclothems that had occurred and were represented in the geologic record. Similarly, there were arguments about the abruptness in the change of the geologic record--the sharp break where limestone changed to shale, for example. There were arguments about how the marine-dominant cyclothems of Kansas matched up to cyclothems in other parts of the midcontinent. Most especially, there were arguments about the source of the black shale, the black shale that Moore said was probably nearshore. Moore argued that the shales, and many of the limestones, were so thin that they could only have been deposited by a sea that appeared and then withdrew over a short span of time. Such a sea must have been shallow. Deep seas, he reasoned, could not appear and disappear in such a hurry. Because the limestones and shales were so widespread, these shallow seas must have been extensive. Through the discussion of cyclothems, Moore set the stage for a geologic discussion, or argument, that has continued into the present. While several of Moore's ideas have since been cast out, there is no doubt that he defined the questions, and thus went far in determining the paradigm of twentieth-century midcontinent stratigraphy. Cyclothems continue to dominate much of the discussion of midcontinent stratigraphy, with further refinement of notions about sea-level change and subsequent deposition. Geologists continue to argue the merits and drawbacks of various theories related to cyclic sedimentation.

Moore's work with cycles of sedimentation may have indirectly led to the appearance of his first textbook, Historical Geology, published by McGraw--Hill in 1933 (Moore, 1933c). As the title shows, the book was, like most texts on historical geology, one of sweeping scope, one that took all of geologic time as its province. With his combination of background in geologic history and paleontology, Moore was up to the task. The book is 673 pages of text, figures, and photographs showing the rocks left behind and preserved by the geologic past, and the animals that lived in those times. Moore later revised the book, but its appearance helped push Moore beyond regional renown to national prominence.

Invertebrate paleontology

Moore's second area of expertise was invertebrate paleontology, a specialty particularly handy for studying the geology of the Pennsylvanian and Permian systems, where invertebrate fossils were far more abundant than vertebrates. In fact, it was probably Moore's knowledge of Pennsylvanian paleontology that led to his 1929 publication on the "Environment of Pennsylvanian Life in North America," a paper that served as a precursor to many of Moore's ideas on cyclothems (Moore, 1929). During his career, Moore published specific articles on corals, gastropods, and bryozoans, and considered a number of other invertebrate species at one time or another. But crinoids were his specialty. That sweeping knowledge of invertebrate paleontology eventually gave rise to the beginning, in 1948, of one of Moore's monumental accomplishments, The Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. The Treatise was designed to be the comprehensive survey of invertebrate paleontology. In a series that grew to include 30 volumes, it provided a family-by-family description of fossil invertebrates. In the preface to each volume, Moore wrote that the treatise would include a

"(1) description of morphological features, with special reference to hard parts, (2) ontogeny, (3) classification, (4) geological distribution, (5) evolutionary trends and phylogeny, and (6) systematic description of genera, sub-genera, and higher taxonomic units." (Moore, 1953, p. viii)

Moore later added paleoecology to that list. The Treatise has become a principal reference on paleontological nomenclature, on fossil names and their spelling, on type specimens, on virtually any topic related to invertebrate paleontology. The Treatise was funded by grants from the Geological Society of America and the National Science Foundation, but it was clearly Moore's baby, and he threw himself into its production for more than 20 years; in fact, he was working on it when he died in 1974. The Treatise outlived Moore and continues as a joint publication of KU and the Geological Society of America; revisions and new volumes continue to appear and the work goes on. Still, the Treatise fixed Moore's reputation as a leading invertebrate paleontologist in the mid-1900s, and made him a figure of power and visibility in the geologic community.

Professional standing

Not that Moore had lacked visibility or power before the Treatise. From 1920 to 1926, he was the editor of the Bulletin of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists. From 1930 to 1939, he edited the Journal of Paleontology and from 1931 to 1936, he edited the Journal of Sedimentary Petrology. He started and edited the University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions. Along with those editorial offices, he was, at various times, president of the Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, the Paleontological Society, the Geological Society of America, the Association of American State Geologists, and the American Geological Institute. Honors came to Moore later in his career, including the F.V. Hayden Memorial medal from the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences, the Sidney Powers Memorial Medal from the American Association of Petroleum Geologists, and the William H. Twenhofel Medal from the Society of Economic Paleontonlogists and Mineralogists, the latter named after the man whom Moore succeeded at the Survey.

Perhaps in some other career, a list of publications, offices, and awards would read like a résumé. With Moore, however, it serves to make clear how energetic and expansive a man he must have been. At the same time, no man can be so visible and debate such controversial theories as cyclic deposition without making a few enemies. Moore made his share. While some colleagues remember Moore as a dignified scientific presence, others remember him as acerbic and egotistical. For instance, in a 1957 guidebook by the Kansas Geological Society, Moore announced that "Those who doubted the actuality of Pennsylvanian--Permian cyclothems have ceased to be vocal, and accordingly, the concept of cyclic sedimentation as applied to very many, if not all, areas of those rocks is almost universally accepted. In Kansas it is quite unnecessary to argue or prove. This marks an important gain" (Moore, in Jewett and Muilenburg, 1957, p. 77). That tartness undoubtedly earned Moore enmity within the scientific community. He longed to be made a fellow of the National Academy of Science, remembers one colleague, but was never elected (Hambleton, 1987, personal communication). That enmity was not only confined to fellow scientists. At times, Moore went before the Kansas legislature, only to launch into long academic lectures that did not sit well with members of the Senate and House. In the 1940s and 1950s, other members of the Survey were delegated responsibility to deal with the legislature and Moore concentrated on his own research; while he provided input into determining the Survey's scientific priorities, he was not its only source of direction.

Moore and the Survey

The fourth area of Moore's activity, then, was his teaching at KU and his continued direction of the Survey. At the same time that Moore was establishing his own scientific credentials, the Survey continued to churn out, at the rate of just about one per year, books concerning the state's geology. Most were county geologic reports, standard reference works on the geology of Cloud, Republic, Mitchell, Osborne, Wallace, Ness, Hodgeman, Johnson, Miami, and several other counties. There is no obvious pattern to the Survey's study of the state's geology at that point. It does not focus on oil-producing counties, or even on those in one geographic part of the state.

In the mid-1930s, the Survey began to produce reference works that were basic to study of the state's geology. In 1935, Moore published the first reasonably complete and detailed stratigraphic column of Kansas, based on work done by the Survey (Moore, 1935). In 1937 the Survey published its first large-format, full-color geologic map of Kansas at a scale of 1:500,000 (Moore and Landes, 1937). The map was credited to Moore and Landes, with a tip of the hat to Max Elias and Norman Newell; the map also acknowledged the "active interest" of former Governor Alf Landon, who got his start as a southeastern Kansas oil man before he was governor of Kansas from 1934 to 1936, and then a Presidential candidate. The geologic map was a major contribution to geologic activity in the state; work had started on it in the late 1920s. A revised edition was issued in 1964.

Maxim Konrad Elias.

Moore made two other administrative commitments during the 1930s that may have been more important than any publication the Survey produced. Both were in response to contemporary state concerns. The first, in 1937, was the beginning of a formal cooperative relationship with the U.S. Geological Survey regarding water studies in the state (see Moore, 1940, p. 7). The economy of the 1930s, and accompanying drought and soil conservation problems, had an impact on the Survey's direction. Irrigation had long been used in western Kansas, where rainfall averages as little as 15 inches a year and surface water is scarce. Most of the early irrigation came through water diversions, first from springs and later from a number of ditches and canals that were built to take water from the Arkansas River, especially in southwestern Kansas. With the 1930s drought, the state began to experience problems even with domestic water supply for some of its cities. Where before basic geology and oil and gas had been the dominant focus of Survey study, and water was studied only on an emergency, irregular basis, ground water now took on a considerable, permanent role (although still not one equal to oil and gas). The first cooperative project between the state and federal surveys was in studying the Equus Beds, a shallow aquifer north of Wichita that was, and still is, the primary source of water for the state's largest city. The Equus beds, named after horse fossils that are present there, was among the early formations studied by Erasmus Haworth, but was the subject of renewed concern with the Dirty Thirties drought, Wichita's growth, and worries about saltwater ponds that may have allowed contamination of the water. The surveys studied the local geology and drilled test wells, eventually producing a report on water in the Wichita area. Moore's commitment to cooperative water projects with the USGS has continued up to the present, though the relationship has not always been harmonious. At the same time, the two surveys began cooperative studies of water in a number of southwestern Kansas counties, the Kansas Survey began cooperative projects with other state and federal agencies, including the Soil Conservation Service, the Water Resources Division of the State Board of Agriculture, the State Board of Health, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The Wichita Well Sample Library

While water may have been the focus of growing concern, oil and gas did not lack for attention. In 1938, Moore began work with the Kansas Geological Society to systematically accumulate cutting samples from oil and gas wells drilled in the state (Moore and Landes to Lindley, 26 April 1938, Lindley Collection, KU Archives). Oil production was regulated in the state, but no single repository collected rock samples produced by the drilling that had now shifted its focus from the south-central Kansas and the giant El Dorado field to the Central Kansas uplift of west-central Kansas. Without any systematic collection of samples, petroleum geologists had nowhere to go to study samples when they were considering drilling a well in a specific area. Unless a company had already drilled a number of wells in a given area--circumstances that usually only occurred in large oil companies--such information was not readily available. In Kansas, where the oil and gas business was increasingly dominated by independent operators, obtaining samples from previous wells was difficult.

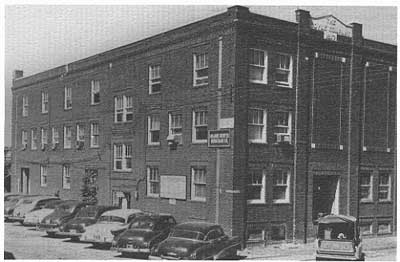

The first Wichita Well Sample Library in downtown Wichita.

The Survey teamed with the Kansas Geological Society to help solve the problem. The Society, based in Wichita, had been formed by the local geologists in 1924, with Moore as one of its charter members. The Society provided a regular forum for its members to meet and listen to lectures from other geologists; it organized field trips that served as the setting for geologists of the time to argue their theories (guidebooks from those field trips became classic references); and it established a well-log bureau where oil companies submitted logs of wells, which could in turn be examined by anyone who was interested. Well-cutting samples were voluntarily sent to the Survey in Wichita, but were not collected systematically, nor were they easily available to the public. That role clearly fit within Moore's concept of the Survey.

A state survey is a continuing institution--a scientific bureau which, through periods of years, gathers and preserves geological information which in many cases might otherwise be lost. The value of such a repository for geological data in a state is seen, for example, in the records of deep wells, samples of drill cuttings, rock specimens and fossils which are brought together for permanent record and reference (Moore, 1924).

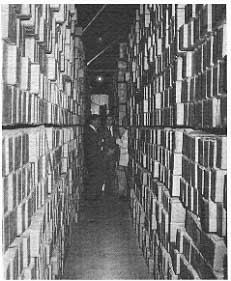

Beginning in 1938, the Survey worked with the Geological Society to make those cuttings available, essentially establishing a joint office in Wichita whose first manager was geologist Raymond P. Keroher. That office has today grown into the Wichita Well Sample Library. In its building on Wichita's west side, the Library houses and makes available cuttings from more than 120,000 wells in the state and continues to collect cuttings from wells in localities not previously represented in the Survey's collection. That facility was built through a fund-raising drive led by the Society, and later expanded using money generated by a fee on every intent-to-drill form filed for oil and gas wells in the state. The Survey also maintains a downtown office, only a few blocks from the Geological Society, that provides information and publications. For a number of years, the Society operated a sample-preparation operation that would wash and dry cuttings, for a charge, before they were submitted to the Survey for archiving. In 1987, the Survey took over the sample-preparation part of the operation, so that it now collects, cleans, archives, and loans the library samples.

Boxes of cuttings at today's Wichita Well Sample Library.

The cooperative program with the U.S. Geological Survey and the establishment of a branch office in Wichita were two of Moore's more successful attempts to deal with state service problems. By teaming with the USGS, he was able to help study state water problems without committing his own resources to the extent that would have otherwise been required. Through the Wichita Well Sample Library, Moore gave the Survey an important presence in Wichita, which had grown into the center of the state's oil industry and had a natural clientele for the Survey's products. Clearly these were both appropriate ideas, ideas that allowed the Survey to carry on its service role without dramatically detracting from the emphasis on basic geology that Moore had picked as his priority.

Moore established one other component of the Survey that has survived into the present. In 1937, he created the Mineral Industries Council, a group of 12 people from outside the Survey who met once or twice a year to provide statewide input on research direction and Survey policies. The members were generally selected to provide geographic and vocational diversity, although their role was also equally political. Examples of early members were Howard Carey, of the Carey salt family, and Kenneth Spencer. Later the name of the Council was changed to the Geological Survey Advisory Council, and it regularly included at least a couple of legislators.

By the end of the 1930s, then, Moore had established the Survey as a larger, far more consequential organization than he inherited 15 years before, both in terms of service activities and academic accomplishment. The Survey of 1940, for example, had a staff of 20 full-time employees divided into five sections: administration; stratigraphy, paleontology, and areal geology; economic geology; subsurface geology; and mineral resources. In addition, the Survey supported staff in cooperative ground-water projects and topographic mapping with the USGS. It also had a part-time staff that boasted some impressive names, including Walter Ver Wiebe, Walter H. Schoewe, and H. T. U. Smith (for more on Smith, see Nichols, 1977).

Moore did not accomplish all those things, scientific and administrative, however, without help. Beginning in 1937, Kenneth Landes was made co-state geologist as well as assistant director, and he handled many of the day-to-day administrative chores related to running the Survey (for more on Landes, see Dorr, 1984). With Moore's increasing involvement in national scientific affairs and overseas travel, such administrative aid was necessary. So necessary, in fact, that when Landes left the Survey to move to the University of Michigan, he was replaced by John C. Frye in 1941. The combination of Moore's scientific work, and his absence for much of the time from 1942 to 1945 working with the Army, meant that Frye was more than looking after day-to-day administrative details. In a real way, he was directing the Survey and looking out for its fortunes.

The Survey changed, then, from the time that Moore assumed its leadership until the late 1940's. It grew. Primarily through Moore's work, it solidified its scientific credentials, and went far to establish the working questions that have dominated midcontinent stratigraphy ever since. It published the books and maps that were the basic tools and references for the state's geologists. With the establishment of cooperative relationships, the Survey moved into an expanded role in state government, going beyond basic geology and oil and gas. As Landes and then Frye took on larger administrative loads, the Survey made evolutionary changes in the nature of its leadership, even though Moore remained tacitly in charge. In the end, however, nearly all those changes revolved, in one way or another, around Raymond C. Moore.

Prev Page--From Haworth to Moore || Next Page--Post-World War II

Kansas Geological Survey, KGS History

Web version February 2003. Original publication date 1989.

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

The URL for this page is http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/Bulletins/227/10_moore.html