Prev Page--Geography and Topography || Next Page--Geologic Structure

Geologic Formations

Geologic time is extremely long. The most tangible indication of this is the thousands of feet of sediment that have been deposited in most parts of the world. The shales of to-day were formed by the deposition and later consolidation of clay or silt-carried into the sea by ancient streams. Sands transported in a similar manner became sandstones. The limestones were formed by the accumulation of calcium carbonate on the sea floor. This compound was carried into the sea in solution and was removed either by animals for the building of shells or by chemical precipitation. Our modern rivers are likewise transporting sand, silt, clay and calcium carbonate, which are deposited on the ocean floor, and the slowness of this deposition gives us some inkling as to the length of time which must have been necessary to build up a series of sedimentary formations hundreds and even thousands of feet thick.

Deposition of sediment is not going on everywhere. On the lands wind and water are removing the rock as it decomposes or disintegrates. In general all areas of the continent above sea level are being eroded, while those areas beneath the sea receive sediment. A study of the rock formations in Kansas shows that there were not only long periods during which the state was covered by the sea, and sand, gravel, silt and lime were being deposited, but there were extremely long times, also, during which the area was dry land and was eroded in exactly the same manner as the wearing-away of the rocks by wind and water at the present. time.

Geologic time may be divided into eras and periods. Eras are the major divisions and may be hundreds of millions of years in length. They are separated from each other by times of unusual crustal disturbance, when the continents were elevated and suffered more or less prolonged erosion. Mountains formed by the deformation of previously deposited rock strata were in some cases obliterated before deposition of sediments on the land was resumed. Periods are shorter than eras and they are separated from each other by lesser disturbances within the earth which cause the seas to shift and in most cases withdraw from the continent. A typical period is represented by thick beds of marine origin separated from beds above and below by an old surface of erosion, called an unconformity. The rocks deposited during a period contain fossils characteristic of the life of that particular time and show whether the beds were formed in the sea or on the land. Subdivisions of periods may be called epochs.

The table [shown below] shows the eras and periods of geologic time and the classification of the formations exposed at the surface in Cloud and Republic counties.

| Table of geologic time divisions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era | Period | Epoch | Rock divisions in area | Summary of events |

| Cenozoic "Recent life" (Age of mammals) |

Quaternary | Recent | Surficial deposits such as sand and alluvium of the flood plains, loess, and dune sand. | Erosion by wind and water. Deposition of silt, sand and gravel by streams and silt and sand by the wind. |

| Pleistocene | Gravel beds, loess. | Ice covered northern part of North America, including northeastern Kansas. Beginning of present drainage lines. Extensive erosion of older deposits. Deposition of gravel and sand in valleys. | ||

| Tertiary | Pliocene Miocene |

Belleville formation, consisting of sand, gravel and clay. | Uplift and rapid erosion of Rocky Mountains with wide-spread deposition over Great Plains as far east as Republic County. | |

| Oligocene Eocene |

Not represented. | Erosion of the land in this region. | ||

| Mesozoic "Middle life" (Age of reptiles.) |

Cretaceous | Carlile shale Greenhorn limestone (Pfeifer shale, Jetmore limestone, Lower Greenhorn) Dakota formation |

Deposition of sand, silt and alcium carbonate in shallow sea covering present area of Great Plains. Sandstone, shale and limestone formed from these sediments. | |

| Jurassic Triassic |

Not represented. | Erosion of the land surface in this region. | ||

| Paleozoic "Ancient life" (Age of invertebrates.) |

Permian Pennsylvanian Mississippian Devonian Silurian Ordovician Cambrian |

Red beds, marine shale, limestone and sandstone (concealed below the surface). | Deposition of marine beds penetrated by deep wells in Cloud and Republic counties. | |

| Proterozoic (Primitive life.) |

Commonly referred to as Pre-Cambrian. Probably represents more than one-half of geologic time. | |||

| Archeozoic (Beginning of life.) |

||||

Reference to the chart will show that the formations exposed in Cloud and Republic counties belong to the Cretaceous, Tertiary and Quaternary periods. The last-named includes the Pleistocene, when the northern part of North America was repeatedly covered by glacial ice, and the Recent, which includes all of the time that has elapsed since the ice disappeared. The Tertiary is the period before the Pleistocene, when there was rapid erosion in the Rocky Mountains and spreading of thick sands and gravels by streams over the neighboring lowlands.

During the Cretaceous, alone, of the periods represented by outcropping rocks in Cloud and Republic counties, was Kansas covered by the sea. This is indicated both by the composition of the Cretaceous rocks and by fossils such as shark teeth, vertebrae of marine reptiles, and shells of marine invertebrates in the sediments of that age. The withdrawal of the seas and the folding of the Rocky Mountains at the close of the period initiated the rapid erosion of the Tertiary. Climatic and other changes, due to the radical change in the earth's surface, caused the decline of the dominant reptilian life of the Mesozoic and led to the rapid development of the mammals during the Cenozoic.

Quaternary

Recent

Flood-plain deposits--The youngest deposits in Cloud and Republic counties are those formed by the present streams and by the wind. The former consist largely of sand and silt deposited over the flood plain in time of flood or under normal conditions in the channel of the stream. Beneath the finer surface deposits are layers of sand and gravel slightly older but of similar origin. These materials have a maximum estimated thickness in the Republican and Solomon river valleys of 50 to 60 feet. Laterally the flood plain deposits merge with the slope wash of the sides of the valley or with the loess or silt deposited by the wind on the bluffs.

In Cloud County the smaller valleys are partially filled with alluvium consisting of silt and clay. This is material derived from the uplands and washed into the valleys in relatively recent times. In Republic County the upland deposits consist of sands and clay, and consequently the creek valleys show a fill consisting of these materials which, in the western half of the county particularly, has a depth of 30 to 40 feet. An excellent exposure of such material may be seen along the creek a mile north and three-fourths of a mile west of Belleville in a bluff south of the road, where the following section was measured:

| Section of creek fill near NW cor. of sec. 34, T. 2 S., R. 3 W. | Ft. | In. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6. | Soil | 2 | |

| 5. | Silt, gray, calcareous. This material is structureless but contains numerous root holes through which water has circulated and has stained the silt a rusty brown | 8 | |

| 4. | Silt, gray, which is very fine-grained and breaks into conchoidal blocks | 2 | |

| 3. | Clay, gritty. This shows horizontal bedding and contains brown rusty layers | 2 | |

| 2. | White calcareous material | 2 | |

| 1. | Clay, sandy. This bed is gray in color, and in addition to being sandy, contains bits of shell weathered from older formations, and also shells of fresh-water snails or gastropods | 3 | |

The fresh-water gastropod shells in the lowermost division of this section are of recent origin, so all of the deposits here described are classed as Recent. The valley filling may, however, have begun as early as the Pleistocene and is undoubtedly going on at the present time.

Eolian deposits--Recent wind deposits consist of loess and dune sand. Scattered sand dunes are found in both Cloud and Republic counties, but are not common. A number of small dunes lie in Republican river valley near Lawrenceburg, while a more prominent one is found east of the Republican four miles south of Norway. An unusually large dune, more than 60 feet in height, occurs 3 miles northwest of Scandia and west of the river. It is clear from the location of these dunes that the almost pure quartz sand of which they are composed came from sand bars along the bank of the river. From this source the sand was carried to its present location by the wind. Dunes in some areas migrate through the movement of the sand from one side of the dune to the other, but the ones that have been mentioned are covered with vegetation and are stationary. There are small areas in Republican river valley, however, where river sand is being blown and is not only making travel over some of the side roads difficult but is also covering valuable farm land. The most interesting dune topography is found alonog Otter creek, 3 miles northeast of Republic City, in Republic County. Here the dunes are small but are closely spaced and cover an area approximately 3 miles long and from one-half to a mile in width. There are no roads across this area, partially because of the difficulty of building and maintaining them, and also because the land is only suited for grazing, and there are consequently few houses in the area. The sand originates through the erosion by wind and water of the sandy formation underlying the uplands. Otter creek valley, with its steep sides, short rugged tributaries, and especially its sand dunes, presents a striking contrast to the fertile, almost flat farm lands surrounding it.

Pleistocene

The Pleistocene is the period during which ice accumulated to such a depth over great areas in Canada and the northern United States that it moved outward in all directions, but principally toward the south, where lobes of ice extended down the principal drainage channels. From the alternation of deposits of material carried by the ice with layers of soil formed during warmer intervals, geologists conclude that the accumulation of ice occurred at least five times. Deposits of clay, sand, gravel and boulders in the northeastern part of Kansas belong mainly to the second glaciation, which is termed the Kansan. Deposition of gravel in some of the principal streams and of wind-blown silt on the uplands was taking place outside of the glaciated area during this period.

The point nearest to the two counties concerned in this report that was reached by the ice of Pleistocene time is the valley of the Little Blue and its tributaries in Washington County. Here, according to Todd, a glacial lake, called Lake Washington, was formed by the damming of the waters of eastward-flowing streams by the ice. [Todd, J.E.: Report on the Glacial Geology of Kansas; unpublished manuscript in the office of the State Geological Survey.] The principal evidence for this lake, as interpreted by Todd, is the line of glacial boulders rafted by floating ice and deposited along the edges of the lake. The boulders are found at an elevation of 1,400 feet, and so it is possible that boulders and gravels of this origin may be found in the bottom of Mill and other creeks northeast of Cuba, where for a short distance the elevation is below 1,400 feet.

Loess--Much of the upland in western Kansas is underlaid by a fine, uniform-grained material that has been referred to as "plains loess." [2. Darton, N. H.: The Geology and Underground Water Resources of the Central Great Plains; U. S. Geol. Survey, Prof. Paper 32, p. 155, pl. 44; 1905.] It is found over a large part of Cloud and Republic counties and ranges in depth from a few inches to 30 or 40 feet. Excellent exposures may be seen on the bluffs south of Republican river and in many of the road cuts in the area. Plains loess consists of dust-like material that. has been derived from weathering of older formations. It is composed of clay particles, extremely fine sand grains and some calcareous and organic materials. When dry it is a light gray to light buff in color. It shows no bedding and is eroded into vertical columns where exposed along the face of a bluff. Small irregular calcareous concretions are found in it locally. Although it is easily pulverized, so that roads through it are extremely dusty during the dry season, it has the surprising property of standing in vertical cliff faces. It weathers to a loamy soil, making the best uplands soil in Cloud and Republic counties.

Plate VII--Loess exposed in road cut at the southwest corner of sec. 13, T. 1 S., R. 5 W., Republic County.

Plains loess is primarily Pleistocene in age. It is still being formed, however, as can be seen from the clouds of dust that rise from the newly plowed fields on a windy day, and the dust deposits formed by windstorms.

Gravel and sand--Gravel and sand of Pleistocene age occur in areas north of Solomon river between Glasco and Simpson, southeast of Glasco, and along the south bluff of the river in the same vicinity. The deposit north of the river near Simpson covers an area of several square miles and lies at an elevation of approximately 1,400 feet, while those to the southeast are 50 to 60 feet lower. The deposits are more or less continuous and not more than 30 feet in thickness.

The gravel varies in structure and coarseness even in one pit, yet the description of one serves to show the general character of the deposit as a whole. The gravel in the Chris Weaver pit in the northwestern quarter of sec. 32, T. 7 S., R. 5 W., has a thickness of 14 to 16 feet. The material ranges in size from fine sand to pebbles an inch in diameter (see analysis). Approximately one-tenth of the material is retained on, the 1/4-inch screen while at least 50 percent may be classed as medium to fine sand. The finer material is composed largely of quartz which is moderately well rounded, while the larger pebbles are nearly flat and are composed mostly of fragments of the near-by outcropping beds of Cretaceous (Lincoln and Jetmore) limestones. Some of the unusual features are (1) fragments of calcite from septaria of the Carlile shale which crops out many miles to the west, (2) shark teeth and reptile vertebrae that have weathered from the Jetmore limestone beds, and (3) bones of mammals that lived during the Pleistocene. The deposit is rudely stratified and cross-bedded with the cross-laminae dipping toward the south and southeast. At the base of the deposit are masses of clay 1 to 2 feet in diameter. While the sand and gravel are, in general, loosely consolidated, in some places the deposit is firmly cemented by calcium carbonate.

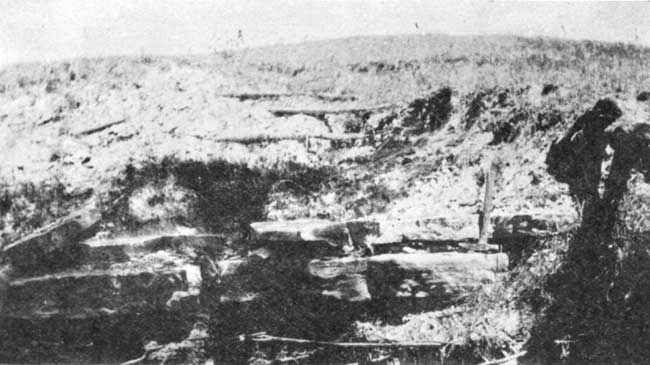

Plate VIII--Chris Weaver sand and gravel pit in the NW sec. 32, T. 7 S., R. 5 W., Cloud County.

The gravel deposits found south of Solomon river occur on the Hugh Beck farm, 4 miles southwest of Glasco, and on the Walter Butler farm, 4 miles south of Glasco. The latter is thicker and more extensive and contains much less clay. Both deposits lie at an elevation of 1,340 feet, which is the same as the lowest part of the deposit north of the river. The material ranges in size from fine clay and sand to boulders a foot or more in diameter. The finer sand and gravel is composed primarily of quartz and limestone while the larger pebbles and boulders are limestone fragments from the Lincoln and Jetmore beds, and ferruginous nodules from the Dakota sandstone in which the ancient valley was cut. The large percentage of calcite in the finer material is due to the presence of internal casts of shells of one-celled animals called Foraminifera, which were weathered from the older Cretaceous formations and washed into the sand. Two genera, Globigerina and Gümbelina, are present. These fossils are both interesting because of their shape and excellent preservation, and important because they are the source of calcite which cements the sand in all of the pits of this region.

Plate IX--Texture of gravel at the face in the Walter Butler pit in sec. 2, T. 9 S., R. 5 W., Ottawa County, south of Glasco.

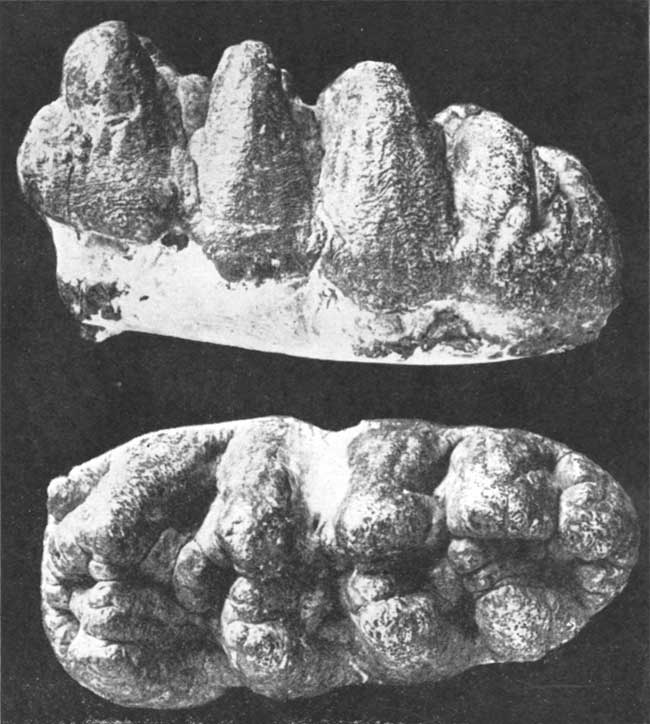

The age of the sand and gravel deposits was determined by the aid of other fossils which were indigenous. An excellently preserved lower jaw bone of a horse was found deep in the sand of the Chris Weaver pit by Lesley Teasley, of Asherville, and donated to the State Geological Survey. It is judged from the size of the bone that the horse must have been as large or larger than the modern draft horse, while the teeth are almost as complicated. The specimen is similar to the teeth and jaw of Equus complicatus Leidy of Pleistocene age. Consequently the deposits have been classified as Pleistocene and are probably equivalent to similar beds found in Russell and Ellis counties to the west and in McPherson county to the southeast. [Rubey, W. W., and Bass, N. W.: The Geology of Russell County, Kansas; State Geol. Survey of Kansas, Bull. 10, p. 19, available online; Haworth, Erasmus: The McPherson Equus Beds; University Geological Survey of Kansas, vol. II, pp. 285-295; 1896.]

Plate X--Side and top views of lower jaw bone of a horse (Equus complicatus Leidy) taken from the Chris Weaver sand and gravel pit near Glasco, Cloud County. About [one-half] natural size.

From the character and structure of the deposits it is clear that they were formed by the early Solomon river. Since their deposition, the river has not only largely removed a fill of 40 or 50 feet of sand and gravel in the valley, but has eroded the channel to a total depth of 60 to 70 feet.

Tertiary

Belleville Formation

Thick deposits of gravel, sand and clay were formed in the Great Plains during the Tertiary period by streams which rose in the Rocky Mountains and flowed eastward. A deposit of this kind, described here for the first time and named the Belleville formation, occurs in the northern half of Republic County. The most prominent feature of this formation is that it occupies a broad but well-defined channel approximately 200 feet deep extending from near White Rock, at the western edge of Republic County, to Chester, Neb. It also extends beyond the old channel onto the uplands, where it has a thickness ranging from 40 to SO feet. North of Belleville the base of the formation rests on an almost flat surface of Carlile shale which slopes gently northward toward the old channel. Farther east the deposit is slightly lower and is in contact in places with the "fence post" limestone. The surface on which the deposit rests has an elevation ranging from approximately 1,600 feet on the uplands near Belleville to about 1,400 feet in the old channel near Chester. The channel itself is nearly 100 feet lower near Chester than at Republic City, showing that the stream flowed eastward.

The limits of the Belleville formation are in some places difficult to determine, since sand and clay derived from it have been washed down the slopes. Near Belleville, however, the basal gravel of the formation is exposed where small streams have cut back into it. The Swierzinsky, McCullough and Hanslick gravel pits, northwest of Belleville, and the Hinal, Keperta, Wocal and Shimek sand and gravel pits, north of Cuba, are near the edge of the deposit. At a great many places along the creeks water seeping from the gravel at the contact with the underlying shale clearly defines the edge of the deposit.

The lithologic character of the formation was studied by an examination of the gravel and sand pits and through the records of water wells. While the formation differs a great deal from place to place, it consists primarily of clay or sandy clay in the upper one-half and sand or gravel in the lower part. Almost every well log shows thin lenses of sand or gravel in the clay and many of the wells pass through a bed or two of clay in the lower gravel. The lower-most few feet of clay in many of the wells are highly calcareous, white, and more or less compact. The clay is listed by the drillers as "magnesia rock." Lenses of this material are not uncommon, however, in other parts of the section, even in the lower gravel beds. The basal part of the formation, as shown in the pits, consists of quartz and feldspar ranging from very fine fragments to pebbles 1/4 inch in size. Most of the material passes through a 10-mesh screen but is retained on the 20-mesh. The quartz grains are moderately well rounded. The feldspar tends to be more rectangular and is gray to pink in color. Occasional pebbles of granite up to an inch in diameter, containing primarily quartz and feldspar, indicate the source of these two minerals. The original source of the granite was the Rocky Mountains.

The stream in which the Belleville formation was deposited flowed from the west. It was comparable in size to Republican river and followed approximately the present course of this river as far east as Republic City. From this point, however, the stream continued toward the north and east instead of turning south as does the Republican. As far as can be determined only one formation fills the channel, although this cannot be determined with certainty. It is clearly of Tertiary age and probably equivalent to a part of the Ogalalla formation of western Kansas, but because of great distance the correlation is made provisionally. [Darton, N. H.: The Geology and Underground Water Resources of the Central Great Plains; U. S. Geol. Survey, Prof. Paper 32, p. 11-8; 1905.]

A number of fossils have been found in the sand and gravel pits mentioned. Unfortunately, however, most of these have been destroyed or permitted to disintegrate by persons who did not realize their importance in determining the age of the beds. Middle Pliocene age is indicated by the identification of teeth of trilophodon, a bunomastodon or long-jawed Proboscidean represented among living forms by the elephant. [Identification by H. T. Martin and Dr. H. H. Lane, of the University of Kansas.] Two teeth were taken from the McCullough pit, of which one was donated to the State Geological Survey by Mr. McCullough and the other loaned for purposes of identification by Dr. W. R. Barnard, of Belleville.

Plate XI--Side and top views of tooth of trilophodon or bunomastodon, one of the long-jawed Proboscidia, taken from the McCullough sand pit northwest of Belleville. [About 80% of] natural size.

Cretaceous

The Cretaceous contains the only marine beds exposed at the surface in Cloud and Republic counties. Reference to the following table shows that four formations are represented--a lower sandstone famous as a water-bearing formation, an intermediate shale, a limestone member, and an upper shale division.

| Cretaceous formations in Cloud and Republic counties | |

|---|---|

| Carlile shale | Undifferentiated |

| Greenhorn limestone | Pfeifer shale Jetmore limestone Lower Greenhorn shale |

| Graneros shale | One member |

| Dakota sandstone | Five members. |

Carlile Shale

The Carlile shale is the uppermost Cretaceous formation exposed in Cloud and Republic counties. Because of its topographic position and its argillaceous character it has been removed by erosion to such an extent that only a thin and badly weathered layer is present capping the uplands. It is so covered with slopewash that relatively few exposures may be seen. The Carlile shale is the "blue slate" encountered by drillers beneath the Tertiary water gravels in Republic County. Where some of the streams have cut back into the gravel, a few feet of the underlying and basal part of the Carlile is exposed.

The total thickness of the Carlile is approximately 280 feet. To the southwest it has been divided into a lower calcareous phase called the Fairport member and an upper noncalcareous part named the Blue Hills shale member. [Rubey, W. W., and Bass, N. W.: The Geology of Russell County, Kansas; State Geol. Survey of Kansas, Bull. 10, p. 40.; Logan, W. N.: The Upper Cretaceous of Kansas; The University Geological Survey of Kansas, vol. 2, pp. 218, 219, 225; 1896.] Although these divisions can be recognized in Republic County the contact between them is not sharp, and consequently the Carlile is not subdivided in this report. While the total thickness is the same as that given for the Carlile in Russell and Ellis counties, the lower calcareous phase is much thicker in Republic County. [Rubey, W. W., and Bass, N. W.: The Geology of Russell County, Kansas; State Geol. Survey of Kansas, Bull 10.; Bass, N. W.: Geology of Ellis County; State Geol. Survey of Kansas, Bull. 11.] It is impossible from the scattered sections taken to give a complete detailed section of the Carlile in Cloud and Republic counties, but the following partial sections show the character of the lower and middle parts of the formation:

| Section of the lower part of the Carlile shale near the southeast corner of sec. 20, T. 12 S., R. 2 W., Republic County. | Ft. | In. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carlile shale: | ||||

| 11. | Limestone, reddish-buff at top | 5 | ||

| 10. | Shale, blue gray; calcareous. Contains numerous Ostrea shells | 5 | ||

| 9. | Limestone, dark buff. Varies greatly in thickness. Splits into thin layers | 3-7 | ||

| 8. | Shale, light gray. Calcareous | 6 | ||

| 7. | Limestone. Splits into three distinct layers. The two upper layers are separated by an ochre-red seam of clay along which the limestone is reddish-buff in color. Middle layer is more compact than the other two and is slightly banded. Lowermost layer is chalky and weathers rapidly | 8-9 | ||

| 6. | Shale, gray. Calcareous | 2 | 10 | |

| 5. | Limestone, gray. Intermediate 1/4-inch is cross laminated | 1 | ||

| 4. | Shale, gray. Calcareous | 2 | 6 | |

| 3. | Limestone. Lower part light buff; upper reddish-buff | 3.5-4 | ||

| 2. | Shale, calcareous | 2 | ||

| Greenhorn limestone-Pfeifer shale member: | ||||

| 1. | "Fence post" limestone | 9 | ||

| Section of the middle part of the Carlile shale exposed along bluff in the SW of sec. 2, T. 2 S., R. 5 W., Republic County. | Ft. | In. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14. | Clay, sand and gravel belonging to the Tertiary | 10-12 | |

| 13. | Shale, blue-gray. Contains lemon-yellow flakes and fragments of large-shelled Inoceramus | 23 | |

| 12. | Bentonite, thin white | 0.5 | |

| 11. | Shale, blue-gray. Contains numerous fragments of large-shelled Inoceramus | 10 | |

| 10. | Clay, brown, containing thin flakes and small crystals of gypsum. Has bentonitic seam at center | 2 | |

| 9. | Shale, blue | 5 | |

| 8. | Gray limestone bed containing many small shells of Inoceramus At the top of this is a zone containing small brownish concretions 1 to 4 inches in diameter | 4 | |

| 7. | Shale, blue | 5 | |

| 6. | Clay, similar to No. 10 | 3 | |

| 5. | Shale, blue papery; containing numerous fragments of large Inoceramus shell and Ostrea | 2 | |

| 4. | Clay, similar to No. 10 | 3 | |

| 3. | Shale, blue | 4 | |

| 2. | Clay, brownish | 1 | |

| 1. | Shale, blue, papery; contains numerous Ostrea shells | 12 | |

The upper 100 feet of the Carlile is not exposed in Cloud or Republic counties, but may be seen under the protecting edge of the Fort Hays limestone in the bluff across the line in Jewell County, a mile southwest of White Rock. Here it consists of papery, noncalcareous shale of light to dark blue-gray color. No fossils were observed in the shale in this locality, and there are only a few of the septarian concretions that are so prominent in this formation elsewhere.

The lower part of the Carlile is lighter in color than the upper. In its unweathered condition it is the same blue-gray, but where weathered it varies from yellow to buff. It contains numerous shells of Ostrea, fragments of a thick-shelled Inoceramus and casts of borings of the worm Serpula. In addition there are brownish fish scales and imprints of the coiled cephalopod Prionotropis woolgari. [Identification by J. B. Reeside, Jr., of the United States Geological Survey.] Because of the large number of Ostrea shells this lower division was first referred to by Logan as the "Ostrea horizon." [Logan, W. N.: The Upper Cretaceous of Kansas; The University Geological Survey of Kansas, Nol. 2, pp. 218, 219, 225; 1896.]

As may be seen in the section, there are a number of thin limestones in the lower part of the formation. The most prominent one occurs 17 feet above the "fence post" limestone and is approximately 5 inches thick. It varies in color from a light buff at the base to a reddish-buff at the top and so may be confused, especially when weathered, with the "fence post" limestone. The lower shale contains also thin but remarkably persistent bentonite clay, a substance that has been ascribed to the weathering of volcanic ash. Some of these layers appear to be unweathered and are white in color, but most are rusty brown. They are characterized by a texture as fine as that of clay, and by a lack of horizontal stratification. Fragments of the material crumble easily into many-sided, very irregular particles. Soil derived from bentonite clay has a peculiar salmon-brown color.

Greenhorn Limestone

The most prominent formation in both Cloud and Republic counties is the Greenhorn limestone. Because the resistance of the limestones in this formation is much greater than that of either the Carlile shale above or the Graneros shale below the Greenhorn is found outcropping along the brow and on the steep slopes of the hills. This formation is readily recognizable, for it contains the only limestones outcropping in either Cloud or Republic County. These white-layered rocks can be seen around the edges of the hills and in many road cuts. Some of the Greenhorn limestones have been extensively quarried and used for fence posts, flagging and building purposes. The top of the formation is the top of the "fence post" limestone and the bottom is the base of the lowest (Lincoln) limestone bed.

In some of the more recent work in western Kansas the Greenhorn has been subdivided into four members, but in Cloud and Republic counties only the upper two are recognized while the lower two are undifferentiated. [Rubey,, W. W., and Bass, N. W.: The Geology of Russell County, Kansas; State Geol. Survey of Kansas, Bull. 10, p. 45.]

| Members of the Greenhorn limestone with characteristics and thickness | Ft. | |

|---|---|---|

| Pfeifer shale: | ||

| "Fence post" limestone bed and underlying gray calcareous shale | 15-16 | |

| Jetmore limestone: | ||

| "Shell rock" at top and thin limestone beds below, alternating with gray calcareous shale | 13-14 | |

| Lower Greenhorn undifferentiated: | ||

| Blue-gray, calcareous shale containing thin crystalline limestones, numerous bentonite-clay layers, and a crystalline limestone bed at the base | 45-53 | |

Pfeifer shale member--The Pfeifer shale member consists largely of yellowish-gray, calcareous shale, although it contains, also, a number of thin limestones in its lower and middle parts and the well-known "fence post" limestone at the top. [Bass, N. W.: Geology of Ellis County; State Geol. Survey of Kansas, Bull. 11, p. 32.] With the exception of the "fence post" limestone the member is not resistant to erosion and consequently has been worn back from the face of the bluff where it outcrops above the Jetmore. The best exposures are seen along some of the creeks where surface wash and loess have been removed.

Plate XII--"Fence post" limestone bed exposed in creek near the southwest corner of sec. 6, T. 3 S., R. 1 W., Republic County.

The "fence post" limestone is the most resistant bed in the member as well as the most distinctive in color and texture. It is light cream-buff in color at the top and bottom, grading toward the center into a much darker band of buff. It is chalky in texture, soft enough to be cut when freshly quarried, but hardens considerably on exposure. It varies in thickness from 6 to 9 inches. Numerous fossils have been found in it, including vertebrae of reptiles and fishes, and among invertebrates imprints of the coiled-shelled cephalopod Prionotropis woolgari and shells of a small pelecypod belonging to the genus Inoceramus. The last-named have a higher, more rounded beak and different surface markings from the Inoceramus labiatus. The "fence post" rock has been quarried extensively in the area and used in building fences, bridges and buildings.

There is a 1- to 2-inch limestone bed just below the "fence post" limestone in Cloud County, but this is less prominent in Republic County than a 3- to 4-inch light buff limestone which occurs 2 inches above. A distinguishing mark is the remarkably persistent 1-inch seam of gray bentonite-clay 5 to 6 inches below the "fence post" bed. Two remarkably persistent limestone beds 2 to 3 inches thick occur 3 1/2 and 4 1/2 feet below the "fence post" limestone. Both are alike in containing thinly laminated layers and in having a background of light cream-buff color with irregular patches of blue-gray. In the lower part of the Pfeifer shale member are many thin layers of limestone which tend to vary in thickness and are discontinuous. These weather into discoidal concretions containing shells of a large but thin-shelled Inoceramus. The more persistent beds are found 14, 28, 36, 60, 70, 80 and 90 inches above the base of the formation.

The Pfeifer shale in this area differs from its exposures in Russell and Ellis counties. The succession of thin beds is not the same and the total thickness is 3 or 4 feet less. In general, however, the member shows the same characteristics and can easily be identified from descriptions given for outcrops, not only in Russell and Ellis counties but as far west as Colorado.

Jetmore limestone member--The Jetmore is the principal limestone member of the Greenhorn. [Rubey, W. W., and Bass, N. W: The Geology of Russell County, Kansas; State Geol. Survey of Kansas, Bull. 10, p. 51.] It consists of the prominent "shell rock" at the top and 12 or 13 thin limestone beds below, alternating with blue or gray calcareous shale. The "shell rock" is approximately 12 inches thick and is characterized principally by the fact that it is the thickest bed of the series. It varies in texture from chalky to finely crystalline, is white or light gray in color, and contains numerous shells of the pelecypod, Inoceramus labiatus. It is difficult to distinguish between the various thin beds of limestone in the lower part of the member except where they are found in place below the "shell rock." In general, however, shells of Inoceramus are more abundant in the upper part of the member, although.they are common in the entire section. Other fossils found are large, coiled cephalopods 5 or 6 inches in diameter, and shark teeth. The latter can be found in relatively great numbers on any weathered slope of the member, particularly after a heavy rain has removed the protecting clay.

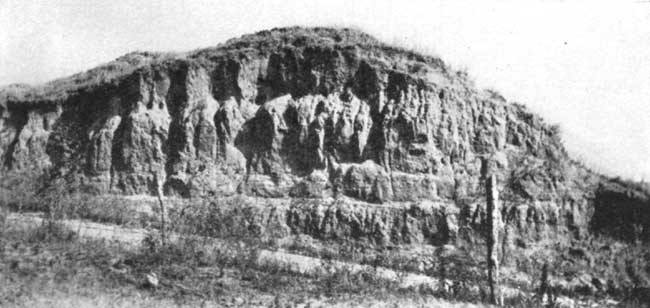

Plate XIII--Uppermost limestone beds of the Jetmore, including the "shell rock" at the top. South side of highway U. S. 36 two and one-half miles east of Belleville, Republic County.

Numerous sections of the Jetmore can be seen in both Cloud and Republic counties, and they show remarkable persistency of even the thinner beds. A single section, therefore, will be sufficient to show the character of the member over the entire area.

| Section of Jetmore chalk member taken from the center of the south Side of sec. 16, T. 6 S., R. 3 W. in road cut on U. S. highway No. 81. | Ft. | In. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 26. | Limestone, fine-grained; gray to light buff; massive, very fossiliferous | 10 | |

| 25. | Shale, thinly laminated; calcareous; light to gray in color; contains many thin limestone beds | 2 | 6 |

| 24. | Limestone, very fossiliferous; gray; fine-grained; compact | 3 | |

| 23. | Shale; thinly laminated; chalky | 1 | |

| 22. | Limestone, fine-grained; whitish-gray; compact; fossiliferous | 4 1/2 | |

| 21. | Shale, thinly laminated; light gray to buff; chalky | 9 | |

| 20. | Limestone, light gray; compact; fossiliferous (Ammonite shell) | 4 1/2 | |

| 19. | Shale, light gray to buff ; thinly laminated; calcareous | 1 | 3 |

| 18. | Limestone, very compact; brown streak in center, light gray | 2 1/2 | |

| 17. | Shale, light gray to buff | 5 | |

| 16. | Limestone, buff streak and limonite concretions in center | 2 1/2 | |

| 15. | Shale, thinly laminated gray to buff; lower 2 inches dark buff | 7 | |

| 14. | Limestone, chalky; gray | 3 | |

| 13. | Shale, thinly laminated; gray | 2 1/2 | |

| 12. | Limestone, fine-grained; white | 4 1/2 | |

| 11. | Shale, thin; light buff | 6 | |

| 10. | Limestone, fine-grained; gray | 2 1/2 | |

| 9. | Shale, thin; buff-colored | 5 | |

| 8. | Limestone, fine grain; light gray to buff | 2 | |

| 7. | Shale, light gray to buff | 5 | |

| 6. | Limestone, compact; light gray | 2 1/2 | |

| 5. | Shale, gray, buff, and tan-colored | 5 | |

| 4. | Limestone, fine grain, compact | 2 | |

| 3. | Shale, light buff and tan, gray | 6 | |

| 2. | Limestone, very compact; rust-colored, limonite concretions in center | 3 | |

| 1. | Lower Greenhorn shale | 17 | |

The "shell rock" and other beds of the member have been quarried extensively in Cloud County and in a few places in Republic County. In these places the more desirable "fence post" limestone is absent and the "shell rock," particularly, is used as a substitute in building fences and for other purposes.

Lower Greenhorn shale--The lower part of the Greenhorn limestone consists of calcareous shale containing a moderately prominent limestone at the base and a number of thin crystalline limestones at various places in the section. The total thickness is from 45 to 50 feet. The lower Greenhorn is divided into the Lincoln and Hartland members in the counties to the west. The contact between the Hartland and Lincoln cannot be recognized in either Cloud or Republic County, and because of the similarity of the section from bottom to top they are not separated in this report. Crystalline limestones which are confined to the Lincoln member in Ellis and Russell counties are found within 5 feet of the base of the Jetmore in Cloud and Republic counties. Others occur at distances of 12, 15, 20, and 28 feet below the overlying limestone member, while a slightly more prominent layer occurs at the base of the formation. This lowermost bed was termed the "Lincoln marble" by Cragin, but as it is not a true marble it will be referred to as the Lincoln limestone bed in this report. [Cragin, F. W.: On the Stratigraphy of the Platte Series or Upper Cretaceous of the Plains; Colo. College Studies, vol. 6, p. 50; 1896.] The Lincoln limestone bed is coarsely crystalline, blue-gray when fresh and brownish when weathered. It breaks into very irregular slabs and emits a strong petroleum odor when freshly fractured.

An unusual bed occurs beneath the Lincoln limestone in secs. 22 and 27, T. 2 S., R. 1 W., north of Cuba in Republic County. It consists of a layer of transversely crystalline calcite from 3 to 6 inches thick, which in some places is in contact with the base of the limestone and in others is separated from it by 3 or 4 inches of sandy clay. The calcite has a radiating habit which gives the rock the appearance of cone-in-cone structure. Extending through the center of the bed is a very irregular stylolite seam. Although this layer is moderately thick it is extremely local and is not found beneath the Lincoln limestone in other parts of Cloud and Republic counties.

The thin crystalline limestone beds near the middle and top of the lower Greenhorn shale are white, gray, or blue in color, and range in thickness from a small fraction of an inch to 2 inches. Often a number of beds occur together in a thin zone. They are not as coarse in their texture as the Lincoln limestone bed, but emit the same petroleum odor when broken. In addition to limestone the lower Greenhorn contains many thin layers of bentonitic clay, which differ from the shale in being finer grained, buff in color, and not laminated. The bentonite contains no grit and is structureless. Its origin has been ascribed to the weathering of volcanic ash.

The following section shows the nature of the member in this region:

| Section of the lower Greenhorn in NE sec. 28, T. 7 S., R. 3 W. | Ft. | In. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 49. | Pfeifer shale member | 15 | |

| 48. | Jetmore limestone member | 13 | |

| Lower Greenhorn | |||

| 47. | Shale, flaky; calcareous; zone 18 inches below the top more calcareous and more resistant | 5 | |

| 46. | Bentonite; weathers brown; crumbly | 6 | |

| 45. | Clay, chalky; light gray to buff; not laminated. Contains thin seams of crystalline limestone | 3 | |

| 44. | Shale, calcareous; light gray; brown seam 5 inches from bottom; flaky | 1 | 4 |

| 43. | Clay, bentonite; plastic; dark buff, and blue-gray | 5 | |

| 42. | Limestone, light buff; seam 1 inch below top | 2 1/2 | |

| 41. | Clay, bentonite; light to buff | 3 | |

| 40. | Clay, bentonite; dark buff and blue-gray | 5 | |

| 39. | Shale, poorly exposed | 5 1/2 | |

| 38. | Limestone, crystalline; irregular in thickness; crystalline part blue-gray, remainder chalky; contains bits of shell | 2 | |

| 37. | Shale, calcareous; contains thin seams of limestone and broken bits of shells similar to bed above; grades laterally into blue and buff layered clay | 1 | |

| 36. | Clay, blue and buff; thin seams of crystalline limestone and bentonite | 1 | 6 |

| 35. | Shale, laminated; gray to buff | 2 | |

| 34. | Clay, bentonite | 1/2 | |

| 33. | Shale, blue and brown; layered; many bentonite seams; some slightly calcareous; contains fossils | 3 | 2 |

| 32. | Clay, bentonite | 1 | |

| 31. | Shale, thin layered; calcareous | 4 | |

| 30. | Clay, bentonite; brown and blue | 4 1/2 | |

| 29. | Shale, calcareous; thin layered; fossils | 10 | |

| 28. | Bentonite, clay; dark buff and blue | 3 1/2 | |

| Duplicated in part and continued in southwest corner NW sec. 22, T. 6 S., R. 5 W. | |||

| 27. | Shale, flaky; contains several thin bentonite seams | 2 | |

| 26. | Limestone, thin crystalline | 2 | |

| 25. | Bentonite, buff | 2 | |

| 24. | Shale, flaky; contains several blue-gray and brown bentonite seams and thin crystalline limestone bed | 4 | 2 |

| 23. | Bentonite | 3 1/2 | |

| 22. | Shale, gray | 3 1/2 | |

| 21. | Bentonite | 3 | |

| 20. | Shale, gray; several thin crystalline limestones in top and bottom | 11 | |

| 19. | Bentonite | 2 | |

| 18. | Shale, gray; calcareous | 2 | 7 |

| 17. | Bentonite | 1 | |

| 16. | Shale, gray; calcareous | 3 | |

| 15. | Limestone crystalline; petroleum odor | 2 | |

| Continued in southeast corner SW sec. 6, T. 4 S., R. 2 W. | |||

| 14. | Clay, bentonite; yellow where weathered | 6 | |

| 13. | Shale, thin crystalline limestone beds at top | 1 | |

| 12. | Limestone, banded gray and tan; finely crystalline; discontinuous | 5 | |

| 11. | Shale, tan and gray | 1 | 3 |

| 10. | Limestone, very hard; coarsely crystalline; blue-brown; very petroliferous; nonfossiliferous | 2 | |

| 9. | Shale, tan with gray zones | 11 | |

| 8. | Limestone, dark brown | 1/4 | |

| 7. | Shale, gray and yellow | 11 | |

| 6. | Limestone, gray-brown; fine; nonfossiliferous | 1 | |

| 5. | Shale, yellow brown | ||

| 4. | Limestone, dark brown; crystalline; less coarse and less fossiliferous than basal bed | 3 | |

| 3. | Bentonite clay, white and yellow | 1 | 2 |

| 2. | Shale, dark gray | 1 | |

| 1. | Limestone, dark brown; coarsely crystalline; very fossiliferous, (Lincoln limestone bed of this report) | 3 | |

Graneros Shale

The Graneros shale lies between the Greenhorn limestone and the Dakota formation. Its upper contact is moderately distinct since its shales differ from those above in not being calcareous, and the Lincoln limestone bed lies at the base of the Greenhorn. The lower contact, however, is more difficult to determine, due to the fact that the sandstones in the upper part of the Dakota are massive in some places and thin-bedded and shaly in others. Where the former condition exists the contact is placed at the top of the sandstone. In places where the sandstone is absent the contact is recognized by a change from dark-colored shale containing small flakes of gypsum to sandy powder-blue shale below.

The Graneros shale is a noncalcareous clay shale varying in color from dark blue to black. It contains numerous lemon-yellow flakes of sandstone and transparent crystals of gypsum. In some places there is a bed of brown sandstone near the center and thinner rusty-colored lenses both above and below. The shale weathers to a heavy clay which shows numerous desiccation cracks during the dry season. The formation thins to the north and east. It has a thickness of 60 feet in Hamilton County, 40 feet in Russell County and 30 to 20 feet in Cloud and Republic counties. In its general characteristics, however, the formation is the same in all three localities.

Dakota Formation

Nearly 400 feet of the Dakota formation outcrops in Cloud and Republic counties. This consists of sandstone and shale, the relative proportions being nearly equal but varying from place to place. In general three sandstones can be recognized which, with the intervening shales, constitute five divisions in all. The lowest sandstone crops out in the extreme southeastern corner of Cloud County, where its maximum thickness is approximately 100 feet. Its upper few feet may be seen in the creeks near Miltonvale, while almost its entire thickness is exposed in the creek valley three miles south and a mile east. The following section shows the character of this member.| Section of the lower sandstone member of the Dakota formation center of SW sec. 34, T. 8 S., R. 1 W. | Ft. | |

|---|---|---|

| 5. | Sandstone, medium coarse, dark brown, resistant; caps hills in this region | 10 |

| 4. | Sandstone, fine-grained, buff color, friable | 30 |

| 3. | Sandstone, dark brown, medium coarse; cross-bedded; causes distinct bench | 5 |

| 2. | Sandstone, fine-grained, massive; some of beds cross-bedded | 40 |

| 1. | Sandstone, very fine-grained; cross-bedded | 24 |

The next overlying member is composed of mottled clay shale. It is approximately 100 feet thick and is overlaid in turn by the 20- to 40-foot intermediate sandstone. The latter outcrops at the top of the hills two miles northeast of Miltonvale. The character of these two members is indicated by the following section:

| Sections of parts of the lower shale and intermediate sandstone members of the Dakota formation | Ft. | |

|---|---|---|

| Section 1. Center of NE sec. 19, T. 8 S., R,. 1 W. (200 yards south of Miltonvale station) | ||

| 3. | Sandstone; coarse-grained, brown; cross-bedded with laminae dipping toward south and west | 3 |

| 2. | Shale, clayey, light-colored; light gray, mottled with buff, chocolate red and lavender colors; contains thin seams of rust-colored sandstone and lenses of massive fine-grained sandstone. (Basal part of lower shale) | 34 |

| 1. | Sandstone. (Upper part of lowest sandstone member.) Lower part fine-grained and more or less massive; light buff. Upper part coarser and redder; contains numerous clay-pebble concretions which leave surface pitted | 16 |

| Section 2. Southwest corner NW sec. 11, T. 8 S., R.. 1 W. | ||

| 4. | Sandstone, coarse-grained, dark brown in color; very resistant; causes hills to be flat-topped with sharp edges and steep slope below. (Lower part of middle sandstone member) | 8-10 |

| 3. | Shale, clayey, mottled red, light gray and chocolate color. (Upper part of lower shale member) | 45 |

| 2. | Sandstone, gray: Very hard | 2 |

| 1. | Mottled clay shale similar to that above | 10 |

| Section 3. Northwest corner SW sec. 22, T. 7 S., R. 1 W. South side of creek. | ||

| 2. | Sandstone, medium coarse. (Lower part of middle sandstone member.) Ochre-yellow to dark brown; individual beds 6 inches to 2 feet thick; cross-bedded; lamina average an inch in thickness and dip five degrees to 30 degrees toward the south, southeast and southwest; cross-bedding sharply defined in upper part, indistinct in lower; contains much coarser sand in lower part; top portion of individual beds a conglomerate in which the pebbles are composed of gray clay balls average 1/2 inch in diameter. As these weather out the surface becomes pitted and very rough. Sandstone also contains numerous concretions of different composition. These have been separated into the following:

| 8-10 |

| 1. | Clay-shale, measured from edge of water in creek. Light green, gray, buff and chocolate red; contains fine sand near base but coarse near top. Numerous small concretions resembling worm borings | 24 |

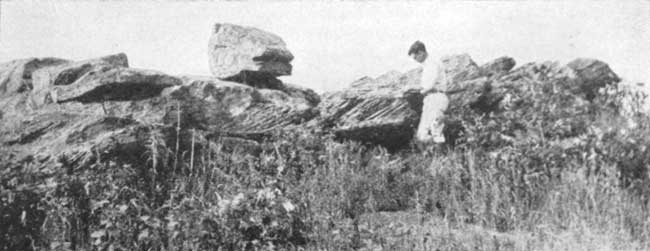

Plate XIV--Cross-bedded Dakota sandstone occurring east of the southwest corner of sec. 25, T. 7 S., R. 1 W., Cloud County.

The upper shale member is similar to the lower in texture and color. It ranges in thickness from 80 to 100 feet and is overlaid by the upper sandstone member, which is 40 to 80 feet thick. The latter outcrops on the hills southwest of Glasco, on the higher hills between Glasco and Miltonvale and on the bluff south of the river near Concordia. Other prominent outcrops occur on the higher knolls in the southeastern part of Republic County. The following section shows the character of the two upper members:

| Section of the two upper members of the Dakota formation, southeast corner sec. 27, T. 8 S., R. 5 W. | Ft. | |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | Sandstone on top of hill; ochre-yellow, red brown, or black; fine to medium-grained; ferruginous; contains numerous concretions and gnarled layers; some of cross-bedding. Beds at 10, 60 and 85 feet above base cause knobs or rough sandstone knolls | 80-85 |

| 1. | Shale; argillaceous; massive; variegated light gray, blue-gray, reddish-purple, red. Small grains of hematite cause red spots. Basal portion grades by long gentle slopes into flood plains | 55 |

As stated previously, the top of the Dakota formation consists in places of shale containing thin lenses of sandstone, but this is not sufficiently persistent to constitute a sixth member.

While the various members of the Dakota thicken and thin, and the shale in some places contains lenses of sandstone and the sandstone layers of shale, the five members outlined are sufficiently prominent to be identified readily in the field. As may be seen in figure 2 these divisions can be recognized also in the logs of wells drilled in Cloud and Republic counties, although there is a tendency for the lowest sandstone member to thin to the north. The five-fold development of the Dakota in Cloud and Republic counties resembles many of the sections of the same formation in Colorado, while if the relatively thin intermediate sandstone is ignored the upper and lower sandstones separated by shale resemble the Dakota, Fuson and Lakota of the Black Hills.

Fig. 2--Graphic presentation of the Dakota formation as shown in well logs.

Many of the characteristics of the different Dakota members are sufficiently general to apply to the entire formation. The shale is argillaceous and mottled. It contains salt and gypsum, which have aided in the disintegration of the rock and have caused salt marshes in some of the creeks tributary to Republican river. The sandstone is commonly brown and contains varying quantities of iron cement, which results in many curiously shaped, gnarled and twisted forms. Concretions are common, although not confined to any particular horizon. At least four types are recognizable as follows: (1) Pyrite concretions found in the shale, (2) masses or balls of sandstone cemented with iron oxide, (3) ferruginous shells filled with loose sand, and (4) concretions similar to the last-described but containing a filling of gray-colored clay.

Black lignite has been reported from various horizons in the Dakota. The only bed observed in Cloud and Republic counties is the one mined near Minersville between Belleville and Concordia. Here the coal is approximately 2 feet thick and is divided slightly above the center by a seam of "black jack" or impure coal. It occurs 12 feet below the top of the upper sandstone member of the Dakota.

The Dakota has been used to a slight extent as a building stone although its lack of uniformity in color, texture and structure prevent its extensive use in this way. Many of the wells in the region obtain water from one of the Dakota sandstone beds. Although the Dakota has been an important source, and much of the water is of excellent quality, in certain areas it contains salt, gypsum and iron and is not suitable for domestic use.

The Dakota formation shows a greater diversity in its surface features than any other formation exposed in Cloud or Republic counties. In eastern Cloud County and along most of Republican river east of Concordia the Dakota country is gently rolling. The same is true of much of the region north and east of Glasco. In relatively small areas, however, such as those already mentioned near Miltonvale, at the twin mounds 10 miles southeast of Concordia, and in a few places east of Talmo, there are relatlvely high ridges and knolls capped by rough brown sandstone. The slopes are steep and strewn with sandstone boulders, while the soil is thin and the land used principally for grazing.

Concealed Rocks

Just as the Dakota underlies the stratigraphically higher and younger formations which occur at the surface toward the west, so the Dakota is underlaid by older formations which appear successively at the surface to the east. One may study these older rocks either by driving eastward across the state or by examining records and samples of deep wells that have been drilled in Cloud and Republic counties.

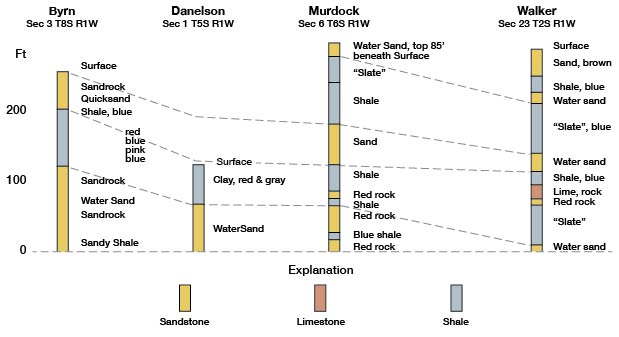

A number of wells have been drilled. Records of two of the more recent ones in Republic County and three from Cloud County have been studied by Dr. J. W. Ockerman of the State Geological Survey, who plotted them as in the accompanying figure. The purpose of the plotting was to show the nature and thicknesses of the formations penetrated by the drill, rather than to indicate structure.

As will be seen from the sections, only the Murdock well (sec. 6, T. 6 S., R. 4 W.) began as high stratigraphically as the Jetmore beds of the Greenhorn limestone. The Walker well (sec. 23, T. 2 S., R. 1 W.) and Kouba well (sec. 24, T. 4 S., R. 2 W.) began practically at the top of the Dakota sandstone, while the Danielson well (sec. 1, T. 5 S., R. 1 W.) began in the lower shale member of the Dakota, and the Byrns well (sec. 3, T. 8 S., R. 1 W.) at the top of the middle sandstone.

The series of shales 300 to 400 feet thick, immediately below the Dakota, is assigned to the Wellington formation of the Permian. The base of this formation, which is so well marked by salt in wells farther south and west, is not as distinct in this area because the salt is missing. It is placed purely on lithologic evidence at the top of a heavy limestone series reached at a depth of between 600 and 700 feet. Absence of salt in the Wellington causes the formation to be much thinner than in wells to the south and west. The limestone unit, 500 to 600 feet thick, lying beneath the shale includes formations of the Marion, Chase and Council Grove groups. The Fort Riley limestone, which is prominent on the bluffs near Manhattan and other limestone beds exposed along the Blue river a short distance east of Cloud and Republic counties, occurs in these groups. Below the limestone series is a shale 500 to 600 feet thick containing a number of thin limestones, which is correlated with the Wabaunsee, Shawnee and Douglas groups. The sandstone found at the base of this unit is thought to be equivalent to similar beds occurring at the base of the Douglas group in Douglas County. Also, in the Douglas group is the Oread limestone caps the hill on which stand the buildings of the University of Kansas.

The heavy series of limestones, ranging from 500 to 600 feet in thickness, below the Douglas is correlated with the Lansing, Kansas City and Marmaton groups. The unusual percentage of thick limestones encountered by the wells corresponds to the thicknesses observed where these formations are exposed at Kansas City and elsewhere in the eastern part of the state. The base of the Pennsylvanian is reached at a depth of slightly more than 2,500 feet, or approximately 2,200 feet below the base of the Dakota formation. Only the Murdock well went into rocks older than the Pennsylvanian. It is believed from a study of the Murdock log that rocks of Mississippian age are absent in the area. The white and green shales in the last 400 or 500 feet may belong to a system of rocks as old as the Ordovician.

While there may be some question concerning the correlation of the units mentioned, there is general agreement on the placing of the base of the Cretaceous at the bottom of the sandstone, from 200 to 400 feet beneath the surface, and the placing of the base of the Pennsylvanian beneath the heavy limestone unit correlated in this report with the Marmaton-Kansas City-Lansing groups. Regardless of the age of the heavy limestone unit, it contains near its middle the Oswald limestone, from which oil is produced in Russell County. This horizon lies between 2,300 and 2,600 feet beneath the surface in Cloud and Republic counties.

Prev Page--Geography and Topography || Next Page--Geologic Structure

Kansas Geological Survey, Geology

Placed on web July 24, 2008; originally published May 1930.

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

The URL for this page is http://www.kgs.ku.edu/General/Geology/Republic/03_form.html