Prev Page--Introduction || Next Page--Geology

Geography

Topography and drainage

Norton and Phillips counties lie entirely within the area designated by Fenneman (1931) as the Plains Border section of the Great Plains physiographic province. The area consists predominantly of moderately fine textured topography having a local relief of 200 feet or less. Flat upland divide areas are present in western Norton County between North Fork Solomon Valley and Prairie Dog Valley and across central Norton County between Prairie Dog Valley and Sappa Valley. The most extensive areas of flat land occur on the prominent terrace surfaces which are well developed along each of the three major valleys.

On the whole, the area is well drained and sloping ground predominates. The lowest points in the area occur along the Norton-Phillips county line on the flood plain of the North Fork Solomon River, and on the flood plain of Prairie Dog Creek where it crosses into Nebraska in north-central Phillips County. At these localities surface altitudes range from 2,000 to 2,020 feet. The highest points in the area are on the major stream divides along the Norton-Decatur county line, where the surface altitude exceeds 2,550 feet.

The Plains Border section grades westward imperceptibly into the High Plains section and in many respects the topography of the Norton-Phillips County area is more comparable to the High Plains topography farther west than it is to the eastern part of the Plains Border section typically displayed in Jewell, Smith, Mitchell, and Osborne counties.

One of the most striking topographic features of this part of Kansas is the pronounced asymmetry of the major eastward-trending valleys. In this area, the valleys of both Prairie Dog Creek and North Fork Solomon River have gently sloping north walls and precipitous south walls. In Norton County the asymmetry of the valleys is so well developed that the drainage basin is also asymmetrical. The north-flowing tributaries are shorter and more numerous, and have steeper gradients than those flowing southward (Pl. 1). This particular characteristic seems to be peculiar to valleys in Kansas and it has been noted elsewhere in the state (Frye, 1945, p. 29; Bass, 1926, pp. 17-23). This feature is illustrated on the two north-south geologic cross sections shown in Plate 3.

Prairie Dog Creek and Sappa Creek, which constitute the major drainageways for central and northern Norton County, flow in a general east-northeasterly direction and join Republican River in southern Nebraska. North Fork Solomon River, however, flows in an easterly direction across Norton and western Phillips Counties but trends in a general southeasterly direction from south-central Phillips County to its confluence with Smoky Hill River at the Saline-Dickinson County line. All three of these major streams head on the surface of the High Plains in Thomas and Sherman counties, Kansas.

Although North Fork Solomon River flows in a slightly different direction from Prairie Dog and Sappa Creeks, the principal tributaries to the three streams exhibit a remarkable parallelism (Pl. 1). Most of the tributaries to the major streams flow either in a south-southeast or north-northwest direction. This alignment causes the north-flowing tributaries to Solomon River and the south-flowing tributaries to Prairie Dog Creek to join the main streams with an acute angle downstream and gives them a somewhat barbed appearance. Another feature that is particularly striking is the difference in texture of the drainage on opposite sides of Prairie Dog Creek. On the south side, where a thin mantle of silt overlies the Ogallala formation, tributary streams are short and closely spaced. This part of the area is well dissected and is used primarily for rangeland. On the north side of Prairie Dog Creek a considerable thickness of silt underlain by the Crete sand and gravel occurs and the drainage pattern is coarse-textured. Slopes are gentle and much of the area is cultivated.

In spite of the well-developed drainage net in Norton and northwestern Phillips Counties the area is not well supplied with surface water. The three major streams are the only perennial streams in the territory, the others carrying water only during and after rains.

Climate

Norton County lies in a region only moderately supplied with rainfall but well supplied with sunshine. The climate is of subhumid type, involving moderate precipitation, moderately high average wind velocity, and rapid evaporation. During the summer the days are hot, but, the nights are generally cool. The summer heat is alleviated by good wind movement and low relative humidity. As a rule the winters are moderate, with severe, cold periods of short duration and relatively light snowfall.

According to data presented by the United States Weather Bureau, the normal annual mean temperature for central Norton County is 52.8° F. In general, the hottest month is July, with a normal mean temperature of 78.5° F., and the coldest month is January, with a normal mean of 27.5° F. The average growing season--that is, the interval between the last killing frost in the spring and the first killing frost in the fall--is approximately 160 days. The normal annual precipitation in central Norton County is 20.81 inches and the normal annual precipitation at Long Island in northwestern Phillips County is 21.41 inches. The range in amount of annual precipitation since 1888 in central Norton County is 29.15 inches--from 9.64 inches in 1910 to 38.79 inches in 1891. The bulk of the precipitation occurs during the growing season, when the average precipitation for the 6-month period in this part of Kansas is approximately the same as that in the Dakotas and three-fourths of the average for Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio.

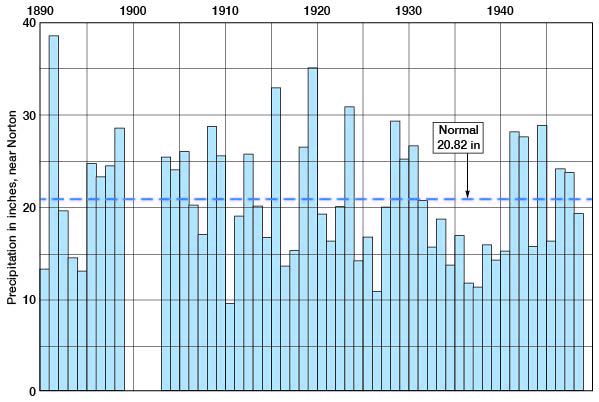

The annual precipitation for the period of record for the station in central Norton County is shown in Figure 3. Charts showing monthly precipitation for the period 1945 through 1947 and the relationship to normal for each month at Norton and at Long Island are presented in Figures 6 and 7.

Fig. 3--Graph showing annual precipitation near North for the period of record and normal precipitation at the station. (Records from the U.S. Weather Bureau.)

Population

According to the 1940 Federal census, the population of Norton County was 9,831, and for 1945 the Kansas State Board of Agriculture reports a population of 8,578 [Note: Norton County population was listed as 5,953 in 2000 U.S. census, with a population per square mile of 6.8 (KU Institute for Policy & Social Research).]. Since the census of 1890 the population of Norton County has shown an increase followed by a decline. In 1890 the population of the county was 10,617. By 1900 it had reached 11,325, and in 1910 it had climbed to 11,614. The 1920 census showed a slight decline to 11,423, but the 1930 census showed the maximum of 11,701. The decrease in population between 1930 and 1940 was 16 percent for the county as a whole, but the rural population declined 22 percent. The 1940 Federal census lists population figures for five cities in Norton County. At that time Almena had a population of 543 (469 in 2000); Clayton, 153 (66 in 2000); Edmond, 180 (47 in 2000); Lenora, 537 (306 in 2000); and Norton, 2,762 (3,012 in 2000). Long Island is the only city in the part of Phillips County covered by this report listed in the 1940 census; at that time it had a population of 257 (155 in 2000). The 1945 Kansas State Board of Agriculture census lists the following population figures for the same cities: Almena, 526; Clayton, 124; Edmond, 119; Lenora, 492; Norton, 2,635; and Long Island, 212.

Transportation

Norton County is crossed by the main line of the Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific Railroad from Omaha, Neb., to Denver, Colo., which traverses the county east-west along the Prairie Dog Valley, passing through Almena, Norton, and Clayton. A branch line of the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy from Alma, Neb., to Oberlin, Kan., also traverses the county east-west, along the Prairie Dog Creek Valley through Long Island, Almena, and Norton, and thence northwestward to Norcatur in west-central Decatur County. A branch line of the Missouri Pacific Railroad extends up the North Fork Solomon Valley from Downs to its terminus at Lenora in southwestern Norton County.

Several hard-surfaced Federal and State highways pass through Norton County and northwestern Phillips County. U. S. Highway 36 passes east-west through Norton County through the City of Norton. U. S. Highway 283 traverses Norton County from north to south through the City of Norton, and U. S. Highway 383 traverses the county diagonally from southwest to northeast, extending from Norton northeast along Prairie Dog Valley through Calvert, Almena, Long Island, and Woodruff. State Highway 9 passes east-west through southern Norton County along North Fork Solomon River Valley through New Almelo, Lenora, Edmond, and Densmore. The remainder of the area is served by numerous improved county and township roads (Pl. 1).

Agriculture

Agriculture is the chief occupation in Norton County and northwestern Phillips County. Virtually all the land in this area is in farms. According to the Kansas State Board of Agriculture, 230,240 acres of major crops were harvested in Norton County in 1945. The distribution of major crops for the years 1941 and 1945 are shown in Table 1. Winter wheat, corn, sorghums, barley, and hay were the predominating crops and a sizable percentage of land was used for grazing purposes.

Table 1--Acreage of principal crops in Norton County in 1941 and 1945. (Data from 1, Kansas State Board of Agriculture biennial reports.)

| Crop | 1941 | 1945 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acres | Percentage | Acres | Percentage | |

| Winter wheat | 74,800 | 31.8 | 95,000 | 41.3 |

| Corn | 70,460 | 30.0 | 81,800 | 35.5 |

| Oats | 3,260 | 1.4 | 3,050 | 1.3 |

| Barley | 32,880 | 14.0 | 6,500 | 2.8 |

| Sorghum | ||||

| For grain | 16,56,0 | 7. 1 | 13,850 | 6.0 |

| For forage | 32,100 | 13.7 | 22,110 | 9.6 |

| All hay | 4,610 | 2.0 | 7,930 | 3.4 |

| Total | 234,670 | 230,240 | ||

Mineral resources

Norton County and northwestern Phillips County are endowed with a diversity of mineral raw materials. The more important mineral resources, aside from ground water, are oil and gas, volcanic ash, and construction materials.

Oil and gas

The first commercial production of petroleum in Norton County was developed by the Phillips Petroleum Company in 1941 when they discovered the Hewitt pool in sec. 11, T. 4 S., R. 21 W. Since that time exploration for petroleum has been active, particularly in the southeastern part of Norton County. It has resulted in the extension of the Ray pool from Phillips County into the extreme southeastern corner of Norton County, and the discovery in 1945 of the Ray West pool in Norton County in sec. 26, T. 5 S., R. 21 W. At the end of 1946 (Ver Wiebe, 1947, p. 58) the cumulative production of the Hewitt pool was 32,050 barrels and that of the Ray West pool was 23,180 barrels. Production is from the Kansas City-Lansing limestone and the Arbuckle dolomite, respectively. Data concerning oil and gas developments and production in the county are listed in the annual reports of the State Geological Survey published as Bulletin 42, covering 1941, and Bulletins 4S, 54, 56, 62, 68, and 75 for the succeeding years. All producing oil wells, abandoned oil wells, and dry wildcat, test holes drilled to the end of 1947 are shown on Plate 1. [Cumulative production as of the end of 2007 was 20,579,170 barrels. Additional information can be found at the oil and gas page of the Kansas Geological Survey.]

Volcanic ash

Volcanic ash is another important mineral resource of Norton County. Active mining of volcanic ash was started in the vicinity of Calvert in 190S and since that time one or more ash mines have been in almost continuous operation. At the present time one large mine is operated at Calvert by the Wyandotte Chemical Co. of Wyandotte, Mich. (Pl. 7A). The ash is mined by the open-cut method, rough-screened in the pit, and hauled by truck less than a quarter of a mile to a screening and storage plant along the rail siding at Calvert. Volcanic ash deposits occur at scattered points throughout the county, and have been mined in several other places. In addition, deposits of commercial thickness were observed at localities where no mining has been undertaken. The location of existing ash mines and unmined deposits of volcanic ash of commercial thickness are shown by symbols on Plate 1. Data on the occurrence and commercial usefulness of volcanic ash are given by Landes (1928) and Jewett, and Schoewe (1942). The results of a petrographic and chemical study of the various ash deposits of western Kansas with special emphasis, on the Norton County area are given by Swineford and Frye (1946).

Construction materials

Several varieties of durable stone uncommon in central and western Kansas occur abundantly in Norton County and northwestern Phillips County (Byrne and others, 1948; 1949.)

The silicified sand and gravel zones or "quartzite" that occur in the Ogallala formation represent, perhaps, the most unusual rock type of the region. This "quartzite" was produced by the cementation of sand and gravel by opaline silica into a very hard and durable rock. It occurs in lenticular deposits and crops out at several localities in southeastern Norton County and northwestern Phillips County. Frye and Swineford (1946) made a detailed petrographic study of this rock and evaluated its usefulness for various purposes. In their conclusions they state (pp. 62-64):

The data presented in this report, supplemented by meager information from local users, indicate that the Ogallala quartzite is far superior to any other deposit in the northwestern part of Kansas and in most cases will probably be suitable for railroad ballast and riprap, and possibly also for a local source of road metal. The unusual coloration and mottled appearance of some deposits should make them desirable for monuments and ornamental stone, and, if economical methods of quarrying and finishing are developed, the quartzite may be useful as a durable building stone. The rock is harder than many others used for such purposes; it is closely comparable in resistance and weathering properties to a good grade of granite. Although it has been reported that Ogallala quartzite has been used locally with success as concrete aggregate, it contains a large amount of opal and caution should be exercised when it is used in concrete or terrazzo, particularly if it is used in conjunction with high-alkali cement, until its suitability for such purposes has been more thoroughly investigated.

Additional data on the occurrence of silicified rocks of the Ogallala formation in Phillips County have been presented by Landes and Keroher (1942, pp. 305-308), and the location of all active and abandoned quarries in the area covered by this report is shown by symbols on Plate 1. The rock has been utilized in the construction of several buildings in Norton and other communities.

Still another rock type of commercial usefulness occurs within the Ogallala formation of Norton County. This is a soft light-gray to white limestone produced by calcium carbonate cement, which binds tightly together a sandy silt. The rock as quarried is predominantly calcium carbonate, and in some zones contains abundant molds of fossil snails. The limestone has been quarried east of Almena and south of New Almelo, where it is used as crushed rock and as building stone. A church and adjacent buildings at New Almelo are constructed from this rock. At some localities the bed that has been quarried is more than 10 feet thick, but at other places it is only 2 or 3 feet thick. Soft limestone is known to occur at several stratigraphic positions within the Ash Hollow member of the Ogallala formation. Active and abandoned quarries of limestone of the Ogallala formation are shown by the quarry symbol on Plate 1.

Although deposits of clean sand and gravel are not as abundant in this area as they are at some places in western Kansas, they have been quarried near Lenora and at several other places throughout the two counties. Sand and gravel mixed with silt is common at many stratigraphic positions within the Ogallala formation, and underlies much of the prominent terrace area along North Fork Solomon River, Prairie Dog Creek, and Sappa Creek. Also, the alluvium under the channel and flood plains of these streams consists partly of sand and gravel deposits.

Soft chalks and chalky shales of the Niobrara formation underlie all of Norton County and northwestern Phillips County. They crop out at the surface at many places along the major valleys. For the most part these chalky shales are too soft to be used for construction, but might be utilized as a source of impure calcium carbonate for some purposes. At a few localities the upper part of this chalky shale has been altered by the addition of silica and a hard flinty rock has resulted. This silicified chalk breaks very much like bottle glass when struck with a hammer, and it has been used to some extent as road material and riprap (Pl. 4B). Its occurrence in Phillips County has been described by Landes and Keroher (1942, pp. 305-308) and active and abandoned quarries in Norton County are shown by a symbol on Plate 1 of this report.

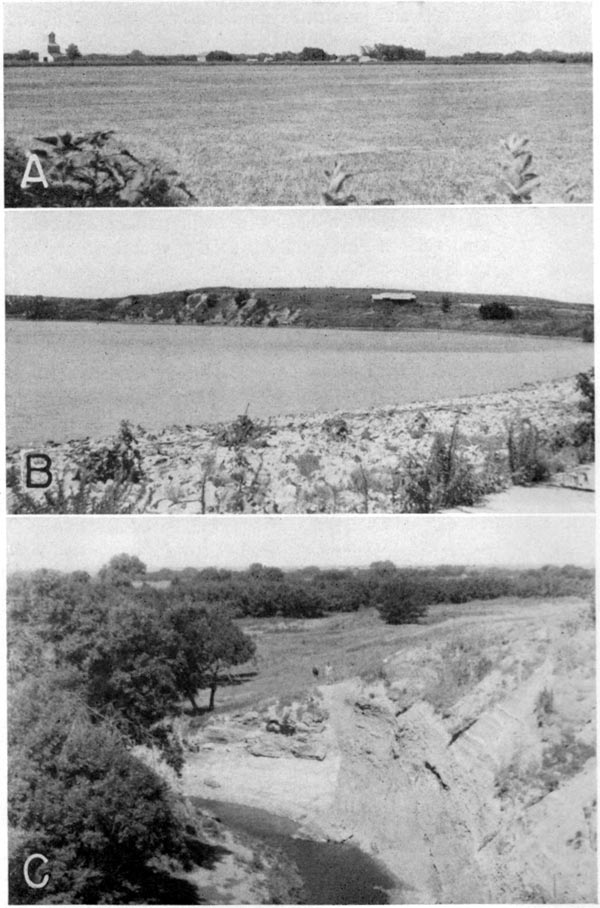

Plate 4--A, Surface of prominent terrace in Prairie Dog Creek Valley at Woodruff, Phillips County. B, Lake Lenora, east of Lenora, southwestern Norton County. Bluff of Niobrara chalk exposed on distant side of lake and riprap of Niobrara chalk on back of dam. C, Prairie Dog Creek Valley, Phillips County. A fault, Niobrara chalk against Pierre shale, is exzposed in the east bank of Prairie Dog Creek.

Ceramic materials

Clay of a type usable for certain ceramic products occurs widely in Norton and northwestern Phillips counties. Deposits of bentonitic clay are known in the basal part of the Ogallala formation in northwestern Phillips County. Data concerning the usefulness of the bentonitic clays have been presented by Kinney (1942). The ceramic character of the widespread loess mantle of the region is described briefly by Norman Plummer in paragraphs immediately below.

Detailed ceramic tests have been made on samples collected from the several members of the Sanborn formation exposed in cuts north of the City of Norton. Data obtained from these tests are presented in Table 2. The firing range was determined to be relatively short (over a range of 5 cones, or approximately 150° F.) but sufficiently great to allow commercial usefulness. Although significant differences among the several members of the Sanborn formation were determined, their characteristics were sufficiently comparable to permit ceramic utilization of the entire thickness of the Sanborn silts at this locality. These clays work well both by hand molding and by stiff mud extrusion, even though they are slightly lean. They are particularly adaptable to stiff mud extrusion. Also, the drying characteristics are good.

Table 2--Ceramic properties of the Sanborn formation, 1 mile north of Norton, central Norton County (Data furnished by Norman Plummer).

| Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Sample 4 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic Properties | ||||||

| Water of plasticity, percent | 20.3 | 23.3 | 21.7 | 25.6 | ||

| Linear drying shrinkage, percent | 3.5 | 4.5 | 2.1 | 6.1 | ||

| Fired Properties | ||||||

| At cone | At cone | |||||

| Fired color 5 | 02 | O | O | Lr | 01 | Lr |

| 4 | Dr | Dr | Dr | 3 | Dr | |

| Linear firing shrinkage | 02 | . 1 | 1.3 | .4 | 01 | 4.8 |

| 4 | 8.9 | 9.3 | 10.7 | 3 | 9.5 | |

| Total linear shrinkage | 02 | 3.6 | 5.7 | 2.5 | 01 | 11.0 |

| 4 | 12.4 | 13.8 | 12.9 | 3 | 15.6 | |

| Absorption (5 hours in boiling water) | 02 | 20.0 | 18.0 | 23.7 | 01 | 12.1 |

| 4 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 3 | 3.0 | |

| Absorption (24 hours in cold water) | 02 | 16.3 | 15.5 | 19.9 | 01 | |

| 4 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 3 | ||

| Saturation coefficient | 02 | .81 | .86 | .84 | ||

| 4 | .64 | .64 | .58 | |||

| Apparent porosity | 02 | 34.3 | 32.0 | 38.1 | 01 | 23.8 |

| 4 | 4.1 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 3 | 6.8 | |

| Apparent specific gravity | 02. | 2.62 | 2.61 | 2.60 | 01 | 2.57 |

| 4 | 2.35 | 2.40 | 2.38 | 3 | 2.45 | |

| Bulk specific gravity | 02 | 1.72 | 1.78 | 1.61 | 01 | 1.96 |

| 4 | 2.25 | 2.29 | 2.27 | 3 | 2.28 | |

| Hardness, as to steel 6 | 02 | S | S | S | 01 | Sh |

| 4 | H | H | H | 3 | H | |

| Firing range (cones) | 02-3 | 01-3 | 01-3 | 02-3 | ||

| Pyrometric cone equivalent (cone) | 8 | 8 | 6-7 | 10 | ||

| 1. Composite of 4 feet of Bignell silt member. | ||||||

| 2. Composite of 2 feet of Brady soil (top of Peoria silt member). | ||||||

| 3. Composite of 12 feet of Peoria silt member. | ||||||

| 4. Composite of 19 feet of Loveland silt member. | ||||||

| 5. O, orange; Lr, light red; Dr, dark red. | ||||||

| 6. S, softer than steel; H, harder than steel; Sh, steel hard. | ||||||

These data, given in Table 2, show that the silts of the Sanborn formation are suitable for the manufacture of red brick, hollow tile, and other structural clay products. Their usefulness for the manufacture of artificial aggregate and railroad ballast has been described by Plummer and Hladik (1948). The several silt members of the Sanborn formation present a uniform aspect and it is probable that throughout the area covered by this report their properties as a ceramic raw material are essentially the same.

Prev Page--Introduction || Next Page--Geology

Kansas Geological Survey, Geology

Placed on web July 18, 2008; originally published Dec. 1949.

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

The URL for this page is http://www.kgs.ku.edu/General/Geology/Norton/03_geog.html