Prev Page--Introduction || Next Page--Stratigraphy

History of Stratigraphic Nomenclature

The earliest classification of Upper Cretaceous strata in the U. S. Western Interior region is that of Hall and Meek (1856), who divided the Missouri River section into units numbered from 1 through 5, in stratigraphically upward order (Table 1). These units were later (Meek and Hayden, 1861, p. 419) given the names Dakota, Fort Benton, Niobrara, Fort Pierre, and Fox Hills, respectively. The existence of chalk in Kansas, belonging apparently to the Niobrara division, was recognized in the 1850s, and Kansas strata comprising "light gray limestone with Inoceramus problematicus" were correlated with division No. 3 before the decade ended (Meek and Hayden, 1857, p. 130). The correctness of this correlation is in doubt, however, because in a later paper Hayden (1872, p. 67) described briefly "chalky limestone of the Niobrara Group filled with Inoceramus problematicus," which he saw at Wilson's Station (= Wilson, Kansas), a place at which the Greenhorn Limestone, rather than the Niobrara Chalk, crops out. Nevertheless, Hayden (1872, p. 67) identified correctly as No. 3 (= Niobrara) the massive beds of yellow chalk that crop out at the summit of a bluff situated 12.8 km (8 mi) west of Hays City [sic], at a place that today is called Yocemento. Mudge (1876, p. 219) accepted Hayden's identification of Niobrara for the beds exposed near Wilson's Station and concluded, because these beds lie directly upon the Dakota, that the Fort Benton is not represented in the Kansas section. Mudge (1878, p. 218) proposed the name "Fort Hays division" for the massive stratum of limestone lying beneath chalk and chalky shales of the "Niobrara proper," and included also within this division all beds lying between the limestone and sandstones of the Dakota. He opined (p. 219) that the lower portion of the Fort Hays (i.e., beds below the massive limestone) may be equivalent to the upper portion of the Benton. In a later work, Mudge (1878, p. 65) included the massive limestone unit in the Benton, and seems to have discarded the name "Fort Hays division" altogether.

Table 1--Historical summary of Upper Cretaceous stratigraphic nomenclature in Kansas, with detailed treatment of the Niobrara Chalk. Earliest uses of present geographic names applied to the formation and its divisions are shown by asterisks. 1, name abandoned; name not only preoccupied but another name has priority; 2, name abandoned, another name has priority; 3, name has priority; reason for abandonment not clear; 4, name abandoned; name preoccupied; 5, first official use of name by Kansas Geological Survey. The name "Niobrara Chalk" was used first by Beecher (1900, p. 267) in a short note concerning Uintacrinus socialis Grinnell.

| WESTERN INTERIOR | KANSAS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEEK & HAYDEN 1856 |

MEEK & HAYDEN 1861 |

MEEK & HAYDEN 1857 |

HAYDEN 1872 |

MUDGE 1876 |

MUDGE 1878 |

ST. JOHN 1883 |

|

| No. 5 | Fox Hills beds | Niobrara Group | Absent in Kansas | Absent in Kansas | Absent in Kansas | ||

| No. 4 | Fort Pierre Group | ||||||

| No. 3 | Niobrara* Division | No. 3 (lower part) |

Niobrara | Niobrara proper |

Niobrara | Niobrara | |

| -?-?-?- | |||||||

| Fort Hays* division (including beds equiv. to Benton) |

Fort Benton | Benton (lss. at top may be Niobrara) |

|||||

| No. 2 | Fort Benton Group | No. 2? | Fort Benton Group | ||||

| No. 1 | Dakota Group | No. 1 | Dakota Group | Dakota Group | Dakota Group | Dakota | |

| KANSAS | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAY 1889 |

WILLISTON 1893 |

CRAGIN 1896 |

LOGAN 1897 |

WILLISTON 1897 |

MOORE & HAYNES 1917 |

JEWETT 1959 |

|||||||

| (Green sand and clay of uncertain age) |

Not mentioned | Arickaree1 shales | Absent in Kansas | (Not represented in Kansas) | |||||||||

| Fort Pierre Group | Lisbon1 Shales | Fort Pierre group | Fort Pierre beds | Pierre shale | Pierre Shale | ||||||||

| Niobrara (incl. sh, w/concr.) |

Niobrara | Niobrara | Smoky Hill* chalk |

Niobrara | Pteranodon beds or Smoky Hill chalk |

Niobrara | Pteranodon beds |

Hesperornis beds Rudistes beds |

Niobrara fm. | Smoky Hill chalk member5 |

Niobrara Chalk 5 |

Smoky Hill Chalk Member |

|

| Benton | Fort Hays beds | Osborne limestone2 |

Fort Hays limestone |

Fort Hays beds |

Fort Hays limestone mbr.5 |

Fort Hays Ls. Mbr. |

|||||||

| Benton | Benton | Victoria shales3 Russell format.4 |

Benton | Benton | Benton formation | Carlile Shale Greenhorn Ls. Graneros Shale |

|||||||

| Dakota | Dakota | Dakota | Dakota formation | (Not mentioned) | Dakota sandstone | Dakota Formation | |||||||

At the time of Mudge's earlier writing, the term "Colorado group" was proposed by Hayden (1876, p. 45) to embrace the Fort Benton, Niobrara, and Fort Pierre divisions. White (1878, p. 21) redefined the Colorado Group, for paleontological reasons, so as to include only the Fort Benton and Niobrara. This concept of Colorado Group has continued to the present day, but in Kansas and most of Colorado lithologic heterogeneity of included strata renders the group of questionable validity and of little practical value.

In a lengthy sketch of Kansas geology, St. John (1883, p. 589) implied that the heavy (= thick) limestone horizons in the upper Benton may belong to the Niobrara, noting that the top of this limestone unit (= top of Fort Hays Member) is "for the most part obscure and difficult to trace." An alternate interpretation of Benton-Niobrara relations was published by Hay (1889, p. 101) who recognized Dakota, Benton, and Niobrara divisions, but included in the Niobrara a thick shale succession containing concretions and "occasional intercalations of limestone" that is now assigned to the Carlile Shale (see Fig. 1).

On the basis of baculite specimens identified by F. B. Meek, deposits at McAllaster Buttes, Logan County, formerly ascribed to the Niobrara, were assigned to the Fort Pierre group by Williston (1893, p. 110), this being the first clear recognition of the group in Kansas. In the same paper, Williston also recognized the Niobrara and Benton, but included the Fort Hays, for which he also used the term "stratified beds," in the Benton.

A major revision of Cretaceous stratigraphic nomenclature in Kansas was presented by Cragin (1896), who gave the entire Upper Cretaceous section the name "Platte Series." In this paper, a number of new formational names are proposed, including Russell formation for strata now referred to the Graneros Shale, Greenhorn Limestone, and Fairport Chalk Member of the Carlile Shale; Victoria formation (or clay) for strata now assigned to the Blue Hill Shale Member of the Carlile Shale; Osborne limestone for beds referred to earlier as the Fort Hays division of the Niobrara; Smoky Hill chalk for the upper division of the Niobrara; Lisbon shales for what is now called Pierre Shale; and Arickaree shales for Pierre beds that he believed equivalent to the lower part of Meek and Hayden's Fox Hills beds. Although three of Cragin's units-Osborne, Lisbon, and Arickaree-had valid formal names and the Russell formation was later divided among three other units, his divisions were based mostly on sound lithostratigraphic criteria, and the name "Victoria shale" certainly should have priority over the present Blue Hill for the upper part of the Carlile.

The Niobrara was accorded group status by Gilbert (1896, p. 566), who recognized two divisions in Colorado, the lower called Timpas and the upper called Apishapa. These names have since been abandoned in favor of Kansas terminology. The first detailed description of Upper Cretaceous strata in Kansas is by Logan (1897a), who recognized many of the Benton divisions to which formal names have been given subsequently. For the lower division of the Niobrara, Logan (1897a, p. 219) used the name "Fort Hays limestone," the upper division being called Pteranodon beds or Smoky Hill chalk. In the same volume, Williston (1897, p. 237 ff.) continued use of the name "Pteranodon beds," instead of Smoky Hill, for the upper division of the Niobrara, and divided these beds, on the basis of color differences, into lower Rudistes beds and upper Hesperornis beds. Logan (1899c) utilized the Williston (1897) classification of the Niobrara in a paper concerning correlation of Colorado formation subdivisions through much of the Great Plains and Black Hills areas. In this work, Logan (p. 91) correlated the Fort Hays limestone with the lower part of the Timpas beds of Colorado, and correlated the Pteranodon beds with the upper Timpas and Apishapa beds.

Moore and Haynes (1917) were first to rank the Kansas Niobrara as a formation, and gave member status to the divisions, namely Fort Hays limestone member and Smoky Hill chalk member. This classification has been in use in Kansas since that date, with the exception that the formational name has been changed to Niobrara Chalk (Jewett, 1959).

Adjacent Stratigraphic Units

Fort Hays Limestone Member, Niobrara Chalk

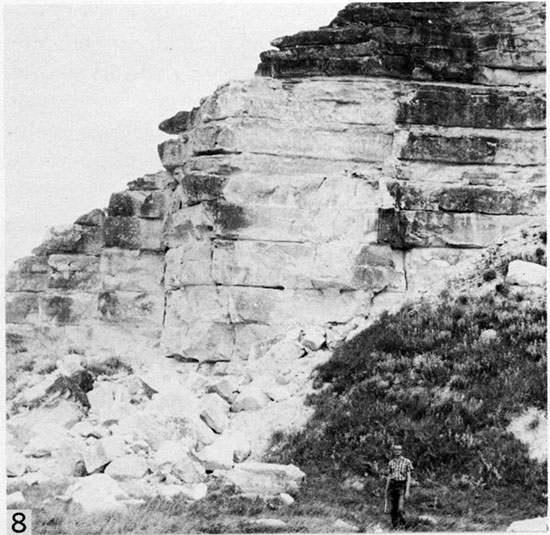

In the Smoky Hill type area, the Smoky Hill Member is underlain conformably by cliff-forming chalky limestone of the Fort Hays Member. An excellent exposure of the Fort Hays is situated in bluffs along Hackberry Creek, Trego County (Fig. 1, Loc. 1), and extends upstream for approximately two kilometers from the confluence of that stream and the Smoky Hill River. A detailed stratigraphic description and graphic column of this section is presented by me (Hattin, 1965, p. 46, 65), and records a thickness of 21.9 m (71.9 ft). The Fort Hays comprises a sequence of thin to very thick beds of relatively resistant, massive, almost entirely bioturbated chalky limestone (Fig. 8). Contacts between these beds are marked commonly by reentrants, some of which formed along very thin partings of shaly chalk and a few of which, in the upper part of the member, are formed along bentonite seams. Part of the section consists of shaly weathering chalk beds, which form major reentrants on the Hackberry Creek cliff face. The sequence of Fort Hays limestone beds, which are probably time parallel, is remarkably consistent along the Smoky Hill River valley (Frey, 1970, p. 9; 1972, p. 14). Principal macroinvertebrate species of the Fort Hays Member are large, bowl-shaped inoceramids, which are invariably encrusted, at least in part, by crowded specimens of Pseudoperna congesta. The oyster Pycnodonte aucella (Roemer) occurs in the lower 8.6 m (28 ft) of the Hackberry Creek section (Loc. 1). Inoceramus deformis Meek ranges approximately from 1.1 m to 8.6 m (3.6-28 ft) above the base of the Fort Hays. Inoceramus (Cremnoceramus) inconstans Woods? ranges approximately from 7.9 to 14.9 m (25.9-48.8 ft) above the base at Locality 1. In the same section Inoceramus (Cremnoceramus) browni Cragin occurs in the interval 9.6 to 14.9 m (31.5-48.8 ft) above the base of the Fort Hays. In the interval from the uppermost occurrence of I. (Cremnoceramus) browni to the uppermost bed of the Fort Hays, fragmentary remains of bowl-shaped inoceramids are relatively sparse, and positive identification of the species represented has not been accomplished. The uppermost bed of the Fort Hays contains well-preserved articulated specimens referred tentatively to Inoceramus (Volviceramus) koeneni Miiller.

Figure 8--Typical exposure of Fort Hays Member. Cliff near mouth of Hackberry Creek, Sec. 25, T. 14 S., R. 25 W., Trego County, Kansas. Note massive beds of chalky limestone, which are characteristic of the member.

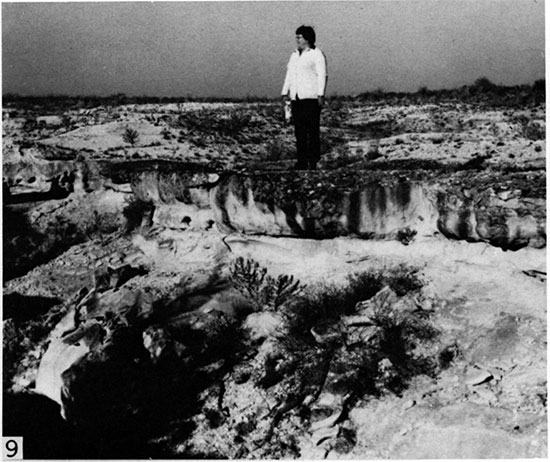

Figure 9--Fort Hays-Smoky Hill contact, Sec. 24, T. 14 S., R. 25 W., Trego County, Kansas. Marge Hattin is standing on a prominent bench formed by the uppermost bed of the Fort Hays. Low slopes in background are formed by less resistant beds in lower part of Smoky Hill Member.

The bed containing Inoceramus (Volviceramus) koeneni is uppermost in a continuous sequence of cliff-forming, bioturbated chalky limestone beds and forms a major bench along the cliff top at the Hackberry Creek site (Loc. 1). The top of this bed marks a conspicuous change in overall appearance of the stratigraphic section (Fig. 9) from ledge-forming chalky limestone to slope-forming, mostly laminated chalk and is designated as the Fort Hays-Smoky Hill contact (Hattin, 1965, p. 65).

Sharon Springs Shale Member, Pierre Shale

Beds of the Sharon Springs Member lie conformably and gradationally on the Smoky Hill. Near the top of the Niobrara section the Smoky Hill comprises chalky shale that grades upward into a calcareous shale interval that contains a few thin beds of noncalcareous gray shale. In the composite section, at Locality 21, the Smoky HillSharon Springs contact is drawn at the stratigraphic horizon above which all of the shale is noncalcareous, and at which a distinctive color change is obvious (Fig. 7). As thus established, the contact lies approximately midway between two thin seams of bentonite, the lower 4.9 cm (0.16 ft) and the upper 4.5 mm (0.015 ft) in thickness. The upper of these bentonites forms a prominent white streak across the exposure.

Lower strata of the Sharon Springs consist mostly of soft, dark gray, silty, flaky-weathering shale and the upper part comprises harder, buttress-forming, organicrich dark gray shale overlain by a thin interval of phosphatic shale (Gill and others, 1972). Basal beds of the Sharon Springs Member contain almost no macroinvertebrate fossils. Field work and drilling suggest that the Sharon Springs is approximately 69 m (225 ft) thick (Gill and others, 1972, p. 7).

Prev Page--Introduction || Next Page--Stratigraphy

Kansas Geological Survey, Geology

Placed on web Feb. 20, 2015; originally published Dec. 1982.

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

The URL for this page is http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/Bulletins/225/03_nomen.html