Prev Page--Stratigraphy--Nebraskan Stage || Next Page--Stratigraphy--Yarmouthian Stage

Pleistocene Stratigraphy in Kansas, continued

Kansan Stage

The Kansan Stage, which appropriately takes its name from Kansas, is quantitatively the most important of the Pleistocene stages in the State. During Kansan time a continental glacier advanced to a position far beyond the limits of the earlier Nebraskan ice and reached the south side of the Kaw Valley as far west as the mouth of Vermillion River. This glacier extended westward across the valley of Little Blue River south of the Nebraska state line. During the retreat of the Kansan glacier water-laid deposits of gravel, sand, and silt accumulated in most of the major valleys in eastern and central Kansas, as an alluvial plain in the Great Bend region, and in minor quantities in the valleys in the northwestern part of the State. The volume of glacial and fluvial sediments assigned to the Kansan Stage far exceeds that of any other Pleistocene stage in Kansas, although eolian sediments of this stage are virtually nonexistent. An event of paramount significance to Pleistocene stratigraphy occurred in latest Kansan time--the distribution over the State of shards of glassy volcanic ash now recognized as the Pearlette bed from a source to the southwest. The Kansan Stage contains the Atchison formation, the Kansas till, and the Meade formation which includes the Grand Island sand and gravel member at the base and the Sappa member with the Pearlette volcanic ash bed.

Definition--The name Atchison formation was proposed in 1951 by Moore and others (p. 15) from exposures in the vicinity of Atchison, Kansas, and particularly the deposits exposed along the creek bank in the SE SW sec. 2, T. 6 S., R. 20 E., Atchison County. A measured section at the type locality is given below. Earlier these deposits had been referred to as pro-Kansan sands (Frye and Walters, 1950, p. 149) and also as Aftonian sands and silts (Frye, 1941). The same deposits had previously been described in this area by Schoewe (1938) and in exposures along the Missouri Valley bluffs north of the City of Atchison by Todd (1920).

| Kansas till and Atchison formation at type locality of Atchison formation. Exposed in creek bank in the SE SWV sec. 2, T. 6 S., R. 20 E., Atchison County, Kansas. | Thickness, feet |

||

| QUATERNARY--Pleistocene | |||

| Kansas till (Kansan Stage) | |||

| 4. Till; clay, silt, sand, gravel, and boulders of limestone, igneous rocks, and pink quartzite, calcareous, tan, with streaks of blue-gray in lower part. The till thickens sharply to the southwest and upstream along the creek bank. | 8.0 | ||

| Atchison formation (Kansan Stage) | |||

| 3. Sand, fine to very fine, thin-bedded, well-sorted to extremely well-sorted, light-tan. | 47.0 | ||

| 2. Sand, coarse to fine, thin-bedded to cross-bedded, tan streaked with orange-brown. | 15.0 | ||

| 1. Sand and gravel, cross-bedded, locally cemented with calcium carbonate. From water level in creek | 8.0 | ||

| Total thickness exposed | 78.0 | ||

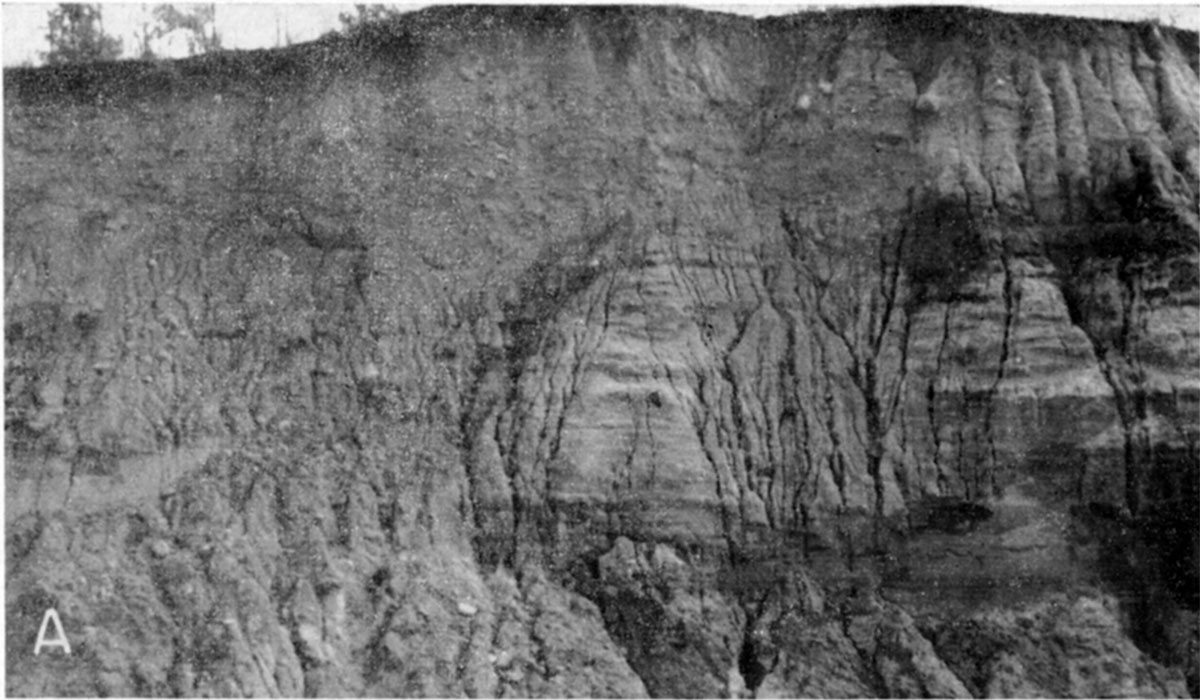

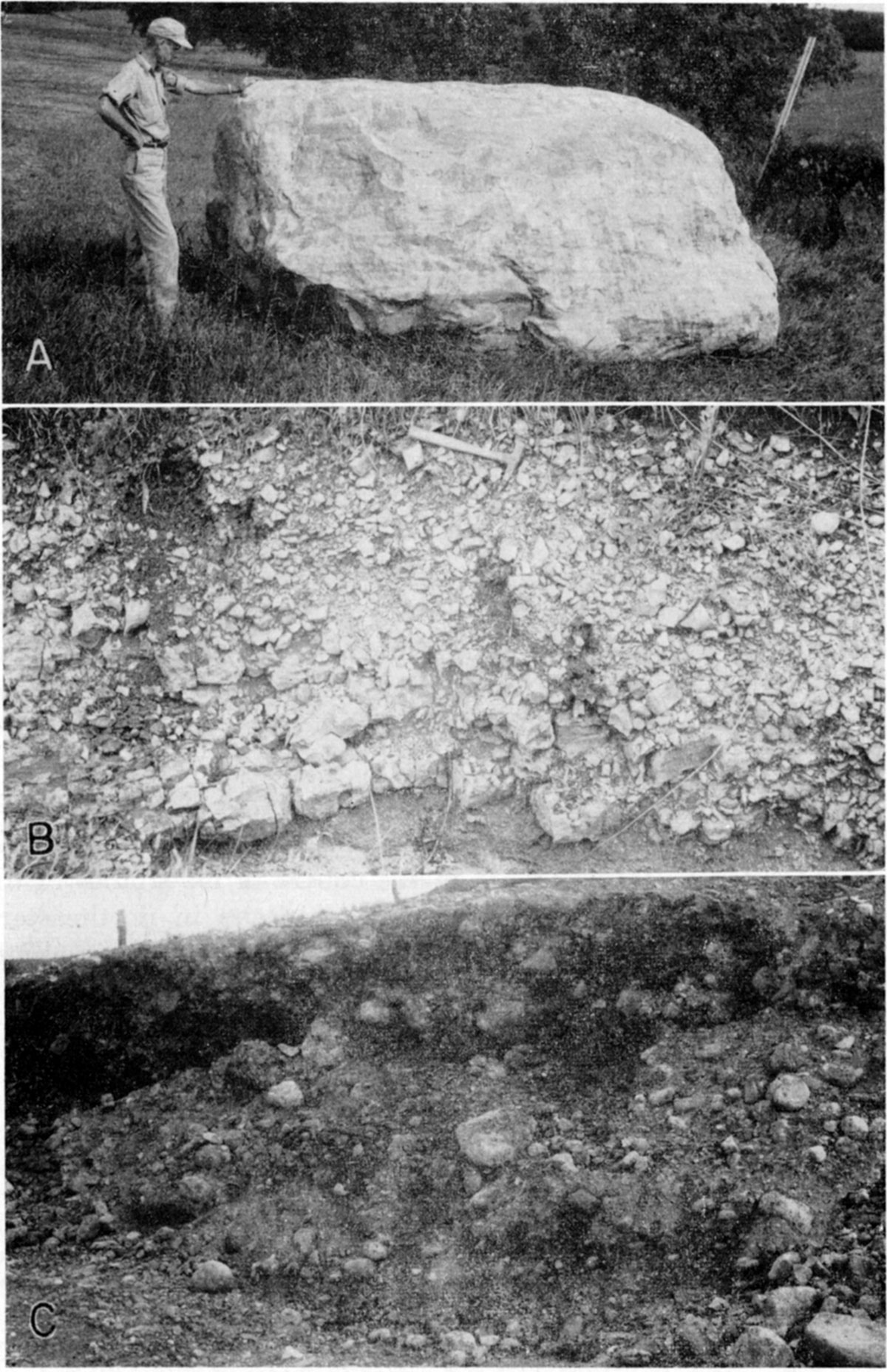

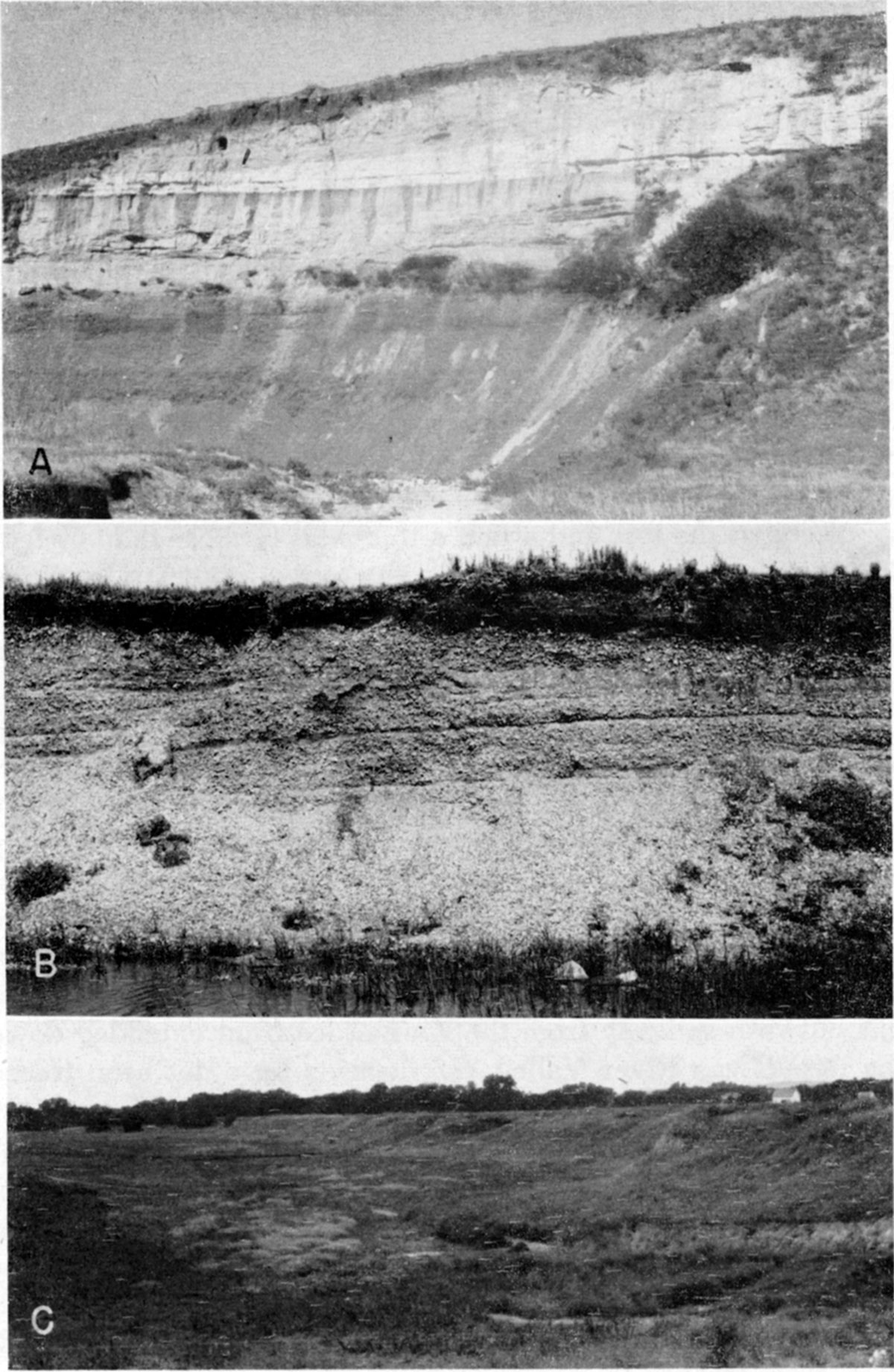

In their definition of the Atchison formation Moore and others (1951, p. 15) stated that the formation, which was not recognized beyond the limits of Kansan glaciation, comprised pro-Kansan outwash of early Kansan age. At the type exposures (Pl. 4A, 4B) 70 feet of Atchison is exposed and a maximum of nearly 100 feet has been penetrated in test holes farther west (Frye and Walters, 1950).

Plate 4A--Type section of Atchison formation, Kansas till at top of exposure; SE SW sec. 2, T. 6 S., R. 20 E., Atchison County (1951).

Plate 4B--Cross-bedded sand and gravel in lower part of Atchison formation, location of A (1951).

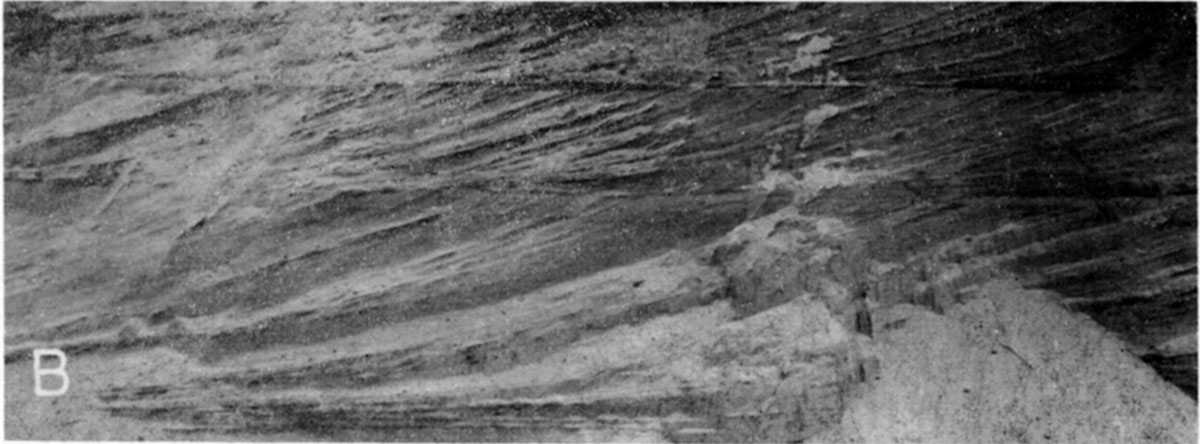

Character and distribution--The Atchison formation consists of silts, sand, and some gravel. At some localities, for example north of Atchison and in Marshall County (Pl. 4C), the coarse silts are extremely well sorted and thin-bedded to laminated. More than 90 percent of some samples of fine sands in the upper part of the type section fall into one Udden grade. Although it is not possible to obtain detailed information from cuttings from fish-tail hydraulic drilling, some samples from the subsurface of southern Nemaha County indicate a comparable lithology. In contrast, coarse gravels occur locally in the formation.

Plate 4C--Laminated fine sand of Atchison formation exposed in creek bank; Kansas till in adjacent exposures; Cen. E. line sec. 13, T. 5 S., R. 10 E., Marshall County (1951).

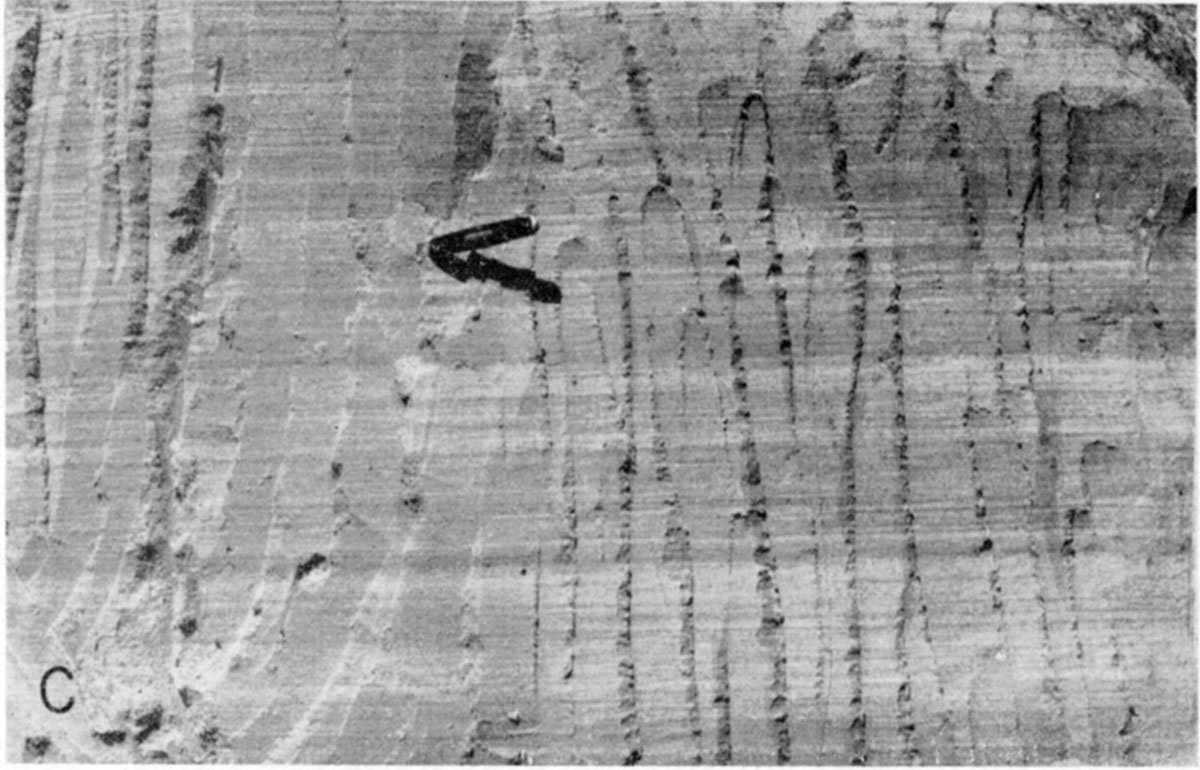

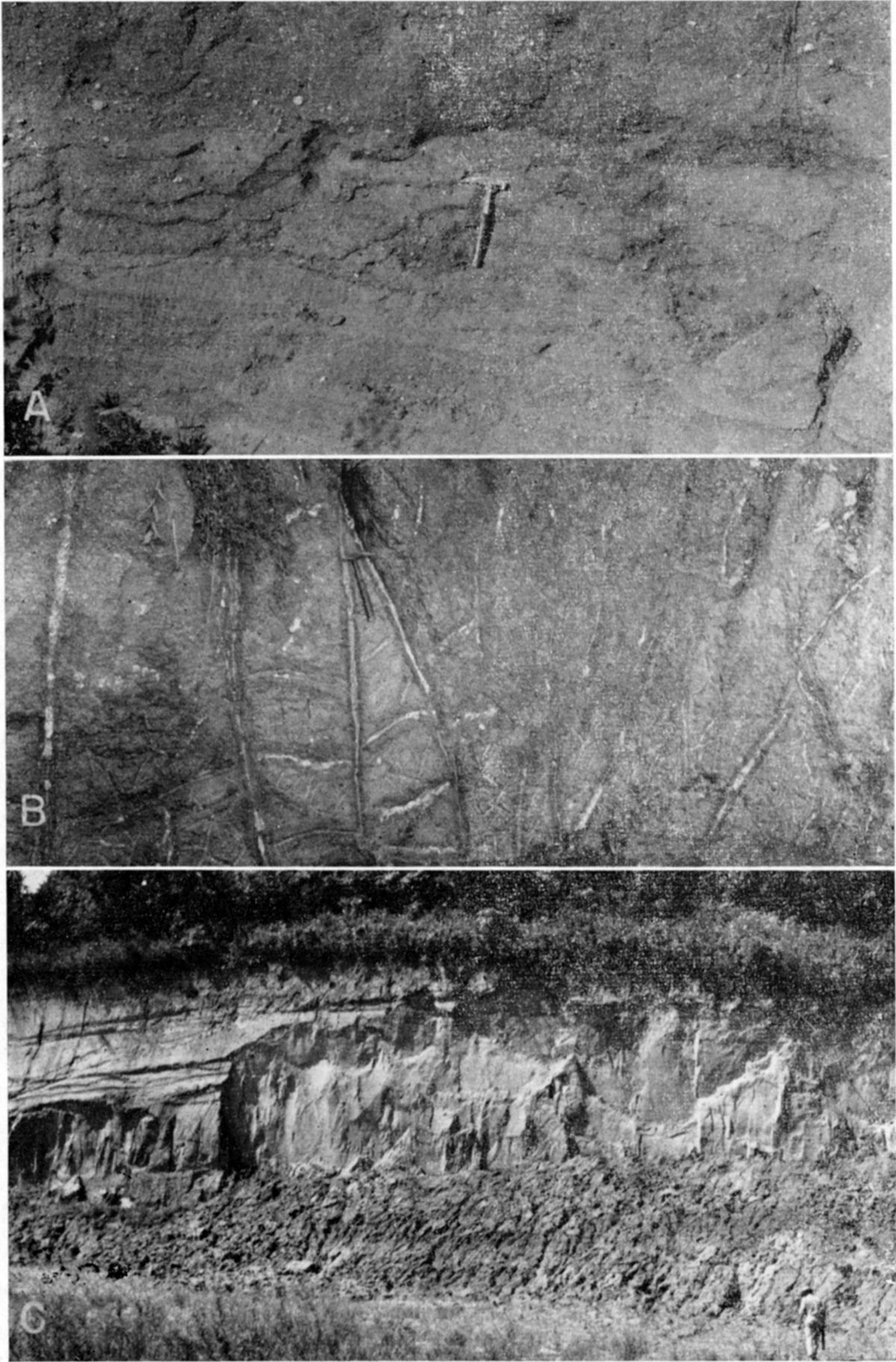

The relation of the Atchison formation to the Kansas till that everywhere overlies it indicates that this formation is genetically related to and only slightly older than the till. No evidence of weathering between the two units has been observed and at some localities till actually interfingers with water-laid sands. These relations suggest that the Atchison was deposited as outwash and lacustrine deposits in pro-glacial lakes produced by the advancing Kansan glacier. As the ice moved across an uneven topography it later overrode these associated water-laid deposits. At a few localities, exposures are adequate to show the effect of scour of these soft deposits by the overriding glacier and to demonstrate incorporation of Atchison sands as blocks and streamers in the overlying till (Pl. 5).

Exposures of the Atchison formation are not numerous. The formation is well exposed in the vicinity of the City of Atchison; in Marshall County (Cen. E. line sec. 13, T. 5 S., R. 10 E.; Cen. E. line sec. 13, T. 4 S., R. 10 E.; NW SE sec. 21, T. 3 S., R. 9 E.); and along the Menoken terrace of the central Kansas River Valley (Davis, 1951; Davis and Carlson, 1952). However, subsurface data indicate that the formation has considerable extent as the lower part of the fill in a pre-Kansan valley that extends from southeastern Marshall County, across southern Nemaha County (where it is overlain by as much as 300 feet of Kansas till), northeastern Jackson County, and central Atchison County (Frye and Walters, 1950). This extensive buried valley, which occurs under a present divide area, is judged to have been cut by a stream localized near the southern margin of the Nebraskan glacier and to have formed a basin of temporary pro-glacial lakes as the Kansan glacier advanced diagonally across it.

Age and correlation--The Atchison formation is by definition pro-glacial outwash and therefore is a stratigraphic unit of different ages at different places. As the Kansan glacier advanced pro-glacial lakes were formed and overridden, and other lakes were formed. Therefore, the Atchison at the type locality may be in its entirety slightly older than the formation where it is exposed in Marshall County and in the central Kaw Valley. In areas at the margin of the glacier the Atchison formation may be inseparable from the earliest phase of retreatal Kansan outwash.

In the plains region of Nebraska beyond the glacial limit, deposits assigned an early Kansan age and approximately equivalent to the Atchison formation have been called the Red Cloud formation (Schultz, Reed, and Lugn, 1951, pp. 547-549; Schultz, Lueninghoener, and Frankforter, 1951). It is named from exposures in Red Cloud Township, E2 sec. 28, T. 2 N., R. 11 W., Webster County, Nebraska. Although at a few localities in central and western Kansas local deposits may be comparable to the Red Cloud of Nebraska, as yet no deposit in Kansas has been firmly correlated with this Nebraska formation. Deposits of questionable correlation have been classed with the Grand Island member of the Meade formation.

The age assignment of the Atchison formation to early Kansan is based on (1) its interfingering relationship to the overlying Kansas till, (2) the universal lack of evidence of weathering in its upper part, (3) its lacustrine bedding and sorting, (4) its merging with retreatal outwash in marginal areas, (5) its lithologic similarity to water-laid material interstratified with the till near the margin, (6) its common occurrence on low bedrock below the expected position of Nebraska till, and (7) the questionable occurrence of eroded Nebraska till below the Atchison deposits at one locality in Atchison County.

Definition--The name Kansan drift was first applied by Chamberlin (1894, 1895) to the lower of the two tills in the vicinity of Afton Junction, Union County, Iowa. Subsequent work by Bain (1897) showed the upper rather than the lower of the two tills in the Union County area to be the one that extends southwestward and forms the surface till of northeastern Kansas. Chamberlin later (1896) transposed the name Kansan drift to the upper till. Although the original description of this formation was based on exposures in southern Iowa, the transposition of the name clearly implies that the surface drift of northeastern Kansas is the type for the unit.

Kansas till, as here used as a stratigraphic unit of formation rank, includes the deposits made directly by the Kansan glacier and some water-laid sediments interstratified with the till. It does not, however, include the pro-glacial silts, sands, and gravels deposited in front of the advancing glacier (Atchison formation) or the outwash deposits from the retreating glacier (Meade formation). A type locality within Kansas has not been specified for the Kansas till and the erection of a type section seems unnecessary after more than 50 years of acceptance of the unit. Appropriate sections of reference within the type area may be considered as the exposures in cut banks approximately one-half mile southwest of the type locality of the Atchison formation (Pl. 5), exposures north of Atchison along the Missouri Valley bluffs (Todd, 1920), and the Iowa Point section in Doniphan County.

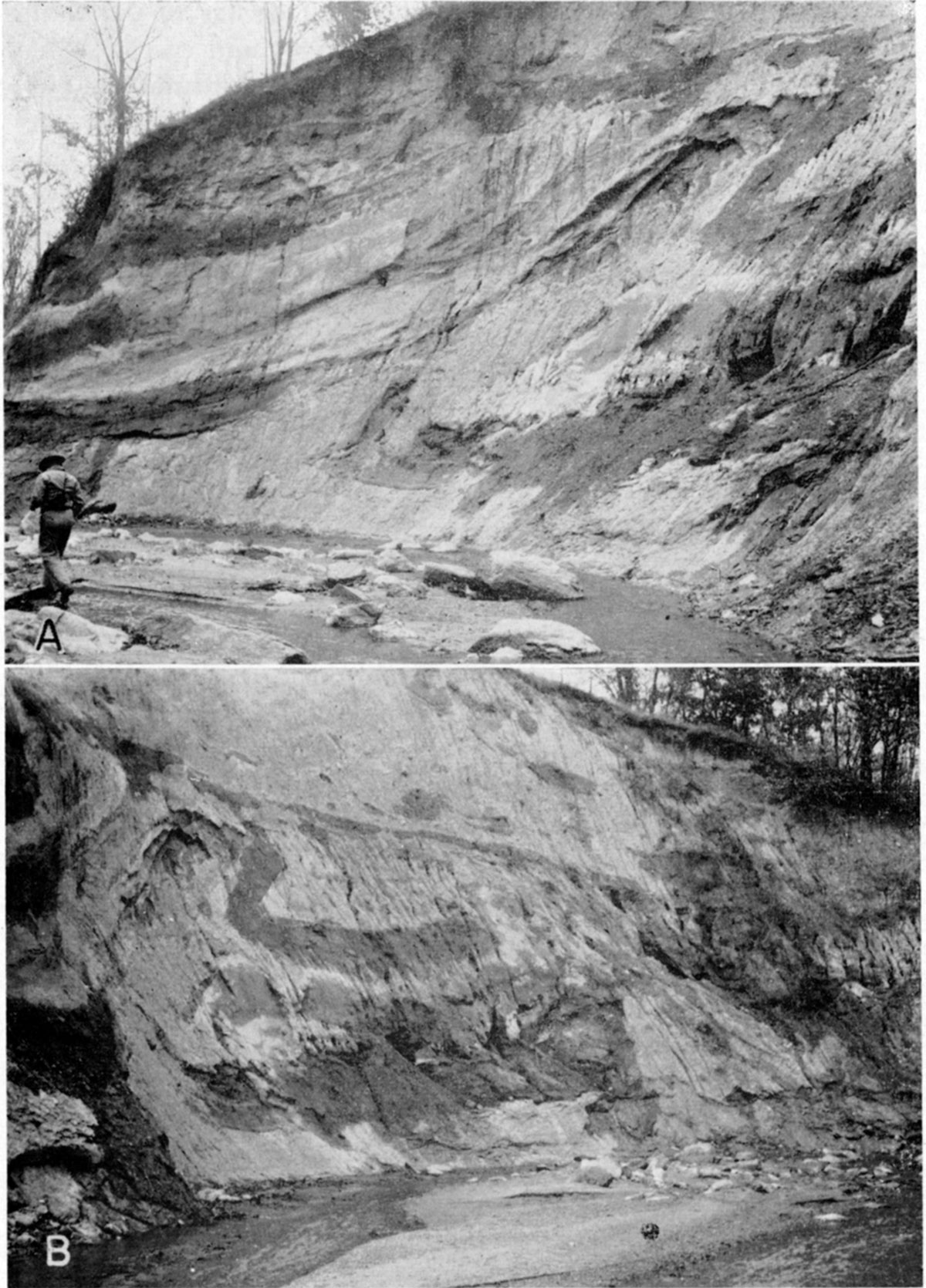

Plate 5--Kansas till southwest of Atchison, Kansas. A and B, Exposures in the NE sec. 10, T. 6 S., R. 20 E., Atchison County, west of type section of Atchison formation. The blue-gray Kansas till is quite uneven in texture and contains contorted "streamers" and "blocks" of well-sorted tan sand and silt, judged to have been derived from the plowing of the underlying Atchison formation by the overriding Kansan glacier (1951).

Character and distribution--Kansas till occurs in the State over much of the area north of Kansas River and east of Little Blue River (Pl. 1). Here, Kansas till, which constitutes the predominant surface material, is extensively exposed in road cuts and natural exposures, except in the parts of Brown and Doniphan counties where it is mantled with thick loess. In the part of the area eastward from central Marshall County and eastern Pottawatomie County little bedrock is exposed and the till is as much as 300 feet thick (Frye and Walters, 1950). At a few localities the Kansas till and the Atchison formation have a combined thickness of approximately 400 feet (Pl. 2).

The area of thick Kansas till terminates abruptly toward the west some distance within the glacial boundary. The deep accumulations of Kansas till are judged to have been importantly influenced by the bedrock surface over which the glacier advanced. A pronounced bedrock sag extends eastward across southeastern Marshall County, southern Nemaha County, northeastern Jackson County, and west-central Atchison County. This bedrock sag, generally containing Atchison formation sands and silts in the bottom and buried beneath the thickest Kansas till in the State, is now a general divide area. Another striking discontinuity in thickness occurs at the eastern scarp of resistant lower Permian limestones in Marshall County and eastern Pottawatomie County. The flat upland divides of north-central Pottawatomie County are mantled locally with 5 to 50 feet of till (for example, NE NE sec. 11, T. 7 S., R. 8 E.) consisting of a rubble of locally derived chert in the lower part (Pl. 6B) resting directly on bedrock, whereas to the north and east till thicknesses on lower bedrock beyond the east-facing scarp are generally from 100 to 200 feet. In northeastern Pottawatomie County thick till is "banked" against the east-northeast face of such a scarp whereas the upland flat west of the scarp is only thinly veneered with till.

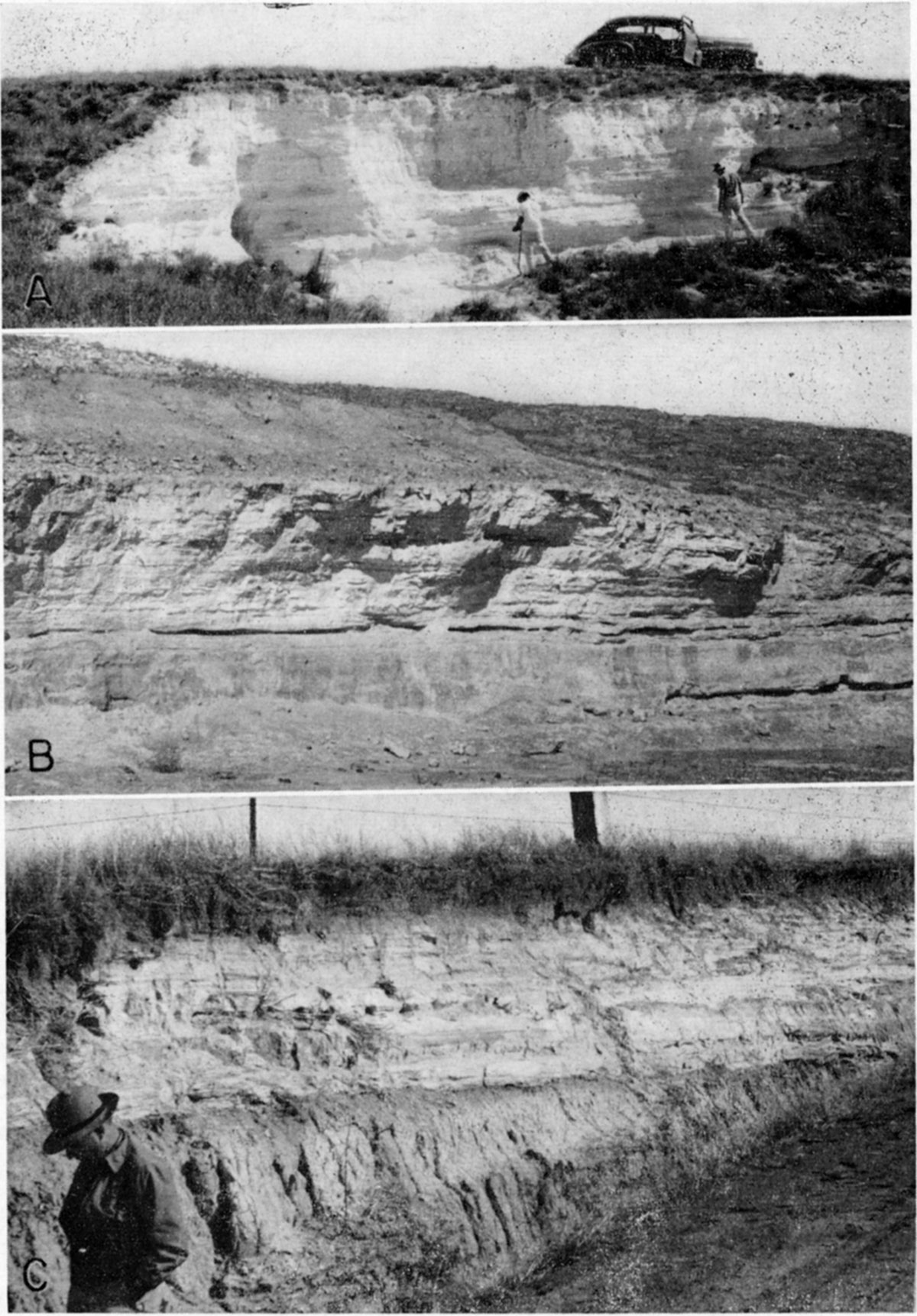

Plate 6--Kansan deposits in northeastern Kansas. A, Large boulder of pinkl quartzite from excavation in Kansas till; sec. 33, T, 3 S, R. 9 E., Marshall County (1951). B, Chert rubble in base of Kansas till on upland in NE NE sec. 11, T. 7 S., R. 8 E., Pottawatomie County. Till rests on Florence flint (1951). C, Kansan outwash (Meade formation) exposed in gravel pit east of Big Blue River Valley; SW SE sec. 16, T. 3 S., R. 7 E., Marshall County (1951).

Westward from central Marshall County, Kansas till is also generally thin and discontinuous. It is exposed west of Little Blue River Valley on the uplands (NW NW sec. 32, T. 3 S., R. 5 E.; SE SW sec. 13, T. 4 S., R. 4 E.) in Washington County. Near the Nebraska state line the westernmost exposure of Kansas till in the State occurs in road cuts in the SE cor. sec. 10 and the SW cor. sec. 11, T. 1 S., R. 4 E., Washington County. Here the till, which overlies sand, silt, and gravel that rests on Permian shale, is interstratified with sand and gravel. The upper part of the deposit contains boulders more than 2.5 feet in diameter.

Southward from northern Jackson County the Kansas till thins toward the Kaw Valley and at many places along the north valley wall has been removed by erosion. A particularly important area for correlation purposes is north-central Shawnee County. Here the Kansas till forms a continuous mantle from the uplands down the valley side where it interfingers with the water-laid deposits of the Menoken (Kansan) terrace of the Kansas River Valley (well exposed in gravel pit in the SW sec. 9, T. 11 S., R. 15 E.).

Exposures of Kansas till south of Kansas River are rare and the till that occurs on the uplands is thin and discontinuous (Pl. 1). At a few places in northern Wabaunsee County and northwestern Shawnee County there are surface concentrations of glacial boulders, but inconclusive evidence indicates that the till, nevertheless, is relatively thin.

Lithologically, the Kansas till is quite similar to the Nebraska till. It ranges from coarse bouldery till to clayey till with dispersed pebbles. Davis (1951) in the course of his studies of the lithology of various sand and gravel deposits in northeastern Kansas, analyzed the 4 to 8 mm size fraction of the Kansas till. He made the following statement as a result of this study (Davis, 1951, pp. 183, 187):

The coarser fraction was washed from four samples of unleached till and one sample of highly weathered till. One count was made of boulders which had been washed by rain from unleached till in an old gravel pit. The lithology of rock fragments in the till varies considerably; however, all unleached samples retained the same general characteristics. Fragments of pebble size and larger constitute less than 5 percent of the volume of the samples. The limestone group is the dominant constituent in the sizes investigated and the shale-sandstone group is next in abundance in the smaller fractions. The total amount of locally derived rocks in the unleached till is in excess of 70 percent. A diagnostic feature of the 4 to 8 mm size pebbles in glacial till and outwash is that the granitic group and the combined dark igneous, miscellaneous metamorphics, and pink quartzite groups occur in roughly equal abundance.

On the basis of 61 pebble analyses from 29 localities in northeastern Kansas Davis was able to recognize significant differences in deposits derived from several sources. He stated the following conclusions (Davis, 1951, p. 191):

Gravel lithology in eastern Kansas varies systematically with the mean diameter of the gravel; therefore, studies of gravel lithology must utilize carefully sized material to obtain the most satisfactory results.

The four most significant gravel types studied were pre-glacial gravel, glacial outwash gravel of Kansan age, gravel from Kansas till, and gravel of Illinoian to Recent age which was transported by Kansas River. The unleached pre-glacial gravel is characterized by a predominance of chert and limestone with lesser amounts of limonite, siltstone, and sandstone. Gravel in unleached Kansas till and in the unleached outwash associated with the till varies considerably in lithology from one locality to the next. However, both retain the following characteristics in the 4 to 8 mm grade size: (a) more than 70 percent of the pebbles are derived from local rocks; (b) limestone is the most abundant rock; (c) granitic rocks are the most abundant erratics; (d) pink quartzite constitutes less than 2 percent of the sample; and (e) the granitic group approximately equals in abundance the combined pink quartzite, miscellaneous metamorphics, and dark igneous groups.

Gravel transported by Kansas River has the following characteristics: (a) the dominating lithologic group in grade sizes larger than 16 mm is chert; (b) the granitic group is dominant in grade sizes between 2 and 8 mm and reaches a maximum of about 60 percent of the sample in the grade size between 4 and 8 mm; and (c) igneous and metamorphic rocks exclusive of the granitic group do not constitute more than 6 percent of any sample.

It is certain that the high percentage of granitic rock in post-Kansan sediments is due not to the introduction of glacial detritus but to the introduction of detritus from the Ogallala formation of western Kansas and southwestern Nebraska. This introduction of Ogallala detritus was initiated by drainage basin enlargements associated with the Kansan glaciation.

Although constituting a relatively minor part of the till volumetrically, pink quartzite resembling the Sioux quartzite of South Dakota is perhaps the most distinctive "marker stone" of the glacial deposits. The pink quartzite fragments are commonly of cobble to boulder size and some very large ones have been observed in areas near the glacial margin (Pl. 6A).

In areas where the Kansas till is thick it is commonly interstratified with sand and gravel deposits as shown by the log of a test hole in Nemaha County, given below. At a few localities (for example, NE NE sec. 14, T. 1 S., R. 10 E., Marshall County; SW NW sec. 27, T. 6 S., R. 14 E., Jackson County, shown in Pl. 7A) water-deposited sand and gravel interstratified with Kansas till is exposed. The sands and gravels at these localities are judged to be deposits of englacial streams or outwash deposited in response to minor oscillations of the ice front. Water-deposited sands of another origin also occur within the body of the Kansas till and are well exposed southwest of the City of Atchison (Pl. 5). Here "streamers," "wedges," and "blocks" of well-sorted sand occur in the till. As the material resembles the subjacent Atchison formation and shows evidence of distortion or movement it is considered to have been incorporated by the overriding glacier from the underlying Atchison deposits.

| Kansas till penetrated in test hole drilled by State and Federal Geological Surveys in the NE NW sec. 31, T. 4 S., R. 13 E., Nemaha County, Kansas. Samples studied by Kenneth Walters. | Thickness, feet |

Depth, feet |

||

| QUATERNARY--Pleistocene | ||||

| Kansas till (Kansan Stage) | ||||

| Clay, silty, noncalcareous, light-gray | 6 | 6 | ||

| Clay, silty, noncalcareous, gray mottled with black | 7 | 13 | ||

| Clay, silty, highly calcareous, gray and tan; contains a few caliche nodules | 4 | 17 | ||

| Clay, silty, with a small amount of sand and gravel, calcareous, tan with reddish-tan | 46 | 63 | ||

| Clay, silty, and sand and gravel with pebbles of quartzite, calcareous, tan | 9 | 72 | ||

| Sand, fine, with some silt and clay, tan | 8 | 80 | ||

| Silt and clay, sandy, calcareous | 5 | 85 | ||

| Gravel, coarse to fine; contains chert and dark igneous rocks; quartz sand | 15 | 100 | ||

| Clay, silty, gravel, and quartzite pebbles, slightly calcareous, tan | 10 | 110 | ||

| Clay, silty, calcareous, tan | 7 | 117 | ||

| Clay, silty, gravelly, calcareous, blue-gray | 6 | 123 | ||

| Sand, medium to coarse, and gravel containing limestone, quartz, and dark igneous grains | 7 | 130 | ||

| Sand, gravel, and clay, tan, calcareous | 5 | 135 | ||

| Clay, silty, sand, gravel, and pebbles of limestone, quartz, and igneous rocks | 70 | 205 | ||

| Gravel, medium to coarse; contains pebbles of pink quartzite, limestone, and dark igneous rocks; some blue calcareous silty clay | 10 | 215 | ||

| Clay, silty, and gravel of dark igneous rocks and limestone, calcareous, blue-gray | 17 | 232 | ||

| Gravel, coarse to fine; contains dark igneous rocks and limestone | 6 | 238 | ||

| Clay, silty, with some medium gravel, calcareous, blue-gray | 6 | 244 | ||

| Gravel, fine, and silty clay, calcareous, blue-gray | 6 | 250 | ||

| Clay, silty, with limestone gravel, calcareous, blue-gray | 50 | 300 | ||

| PENNSYLVANIAN--Virgilian | ||||

| Shale, calcareous, blue-gray | 10 | 310 | ||

| Shale, sandy, calcareous, gray-green | 19 | 329 | ||

| Limestone, light-gray | 1 | 330 | ||

The upper part of the Kansas till is commonly deeply weathered. Test drilling indicates that the depth to which calcium carbonate has been leached from Kansas till varies widely, but commonly does not exceed 10 to 15 feet. At most places the till is oxidized to a tan or brown color at depths considerably below the zone of leaching. A few test holes have penetrated 50 to 60 feet of oxidized till which grades downward into blue-gray unoxidized calcareous till. In many areas where the surface topography is gently rolling and the till is thick, well-developed joint systems occur to considerable depth in the till. These joints commonly have oxidized brown rinds and at many localities a concentration of calcite along the joint (Pl. 7B). This calcium carbonate accumulation has been observed to be as much as 2 inches thick.

Plate 7--Pleistocene deposits in northeastern Kansas. A, Sand and gravel interstratified with Kansas till; SW NW sec. 27, T. 6 S., R. 14 E., Jackson County (A.R. Leonard, 1949). B, Joints in Kansas till showing oxidized rinds and calcite fillings along joint plane, SW sec. 12, T. 2 S., R. 10 E., Marshall County (A.R. Leonard, 1949). C, Bignell and Peoria loess of the Sanborn formation, NE SE sec. 7, T. 2 S., R. 20 E., Doniphan County (Iowa Point section). Bignell loess is 35 feet thick, fossiliferous, and rests on deep Brady soil developed in top of Peoria loess near base of exposure (1948).

Locally at the upland level in southwestern Atchison County, northern Shawnee County, Jefferson County, and Jackson County, a massive clay layer overlies the Kansas till. This clay layer has been informally referred to as the "Nortonville clay" from exposures in the NE sec. 12, T. 7 S., R. 18 E., Atchison County, along road cuts north of the City of Nortonville. At this locality it is a light-gray massive plastic clay nearly 30 feet thick. It rests on oxidized and calcareous till with nodules of caliche and is overlain by a few feet of leached Peoria loess. Although largely noncalcareous to the acid bottle, it contains a few nodules of caliche and some scattered sand grains in the lower part. It is framed stratigraphically between the Kansas till below and the Peoria loess above, and therefore its possible age is late Kansan to Sangamonian. Although its exact age and mode of origin are not known, present data are judged to indicate that these clays were deposited in slight initial depressions on the surface of the newly formed Kansas till plain as the Kansan ice front retreated, and perhaps in some places in ice margin lakes on the flat areas between outwash spillways. Supporting evidence for such an origin consists of its restriction to upland positions where the till plain is not deeply dissected, its unusually high clay content, and the absence of a fully developed soil profile on the till below the clay. Other suggested origins include the alteration of a layer of Loveland loess or solfluction deposits of Illinoian age. That it is not a soil gley layer, or gumbotil, which it superfically resembles, is demonstrated by its relation to the underlying till and the absence of resistant pebbles, common in the till.

It is probable that the "Nortonville clay" of northeastern Kansas is comparable to the material which occurs in a similar stratigraphic position in northern Missouri and was called "gumbotil" by Krusekopf (1948, pp. 413-414). He has described these Missouri clay deposits and it has been demonstrated (Hseung, Marshall, and Krusekopf, 1950) that they cannot be accounted for by soil-forming processes, but, by referring to them as "gumbotil" he has further confused the meaning of that term. As gumbotil is used by some workers in a genetic sense to apply to humic-gley soils or Planosols (for example the Afton soil at the Iowa Point section) and by others in an objective lithologic sense applying to sediments of diverse origins, the term is not generally used in Kansas literature.

Age and correlation--Kansas till has been generally accepted as type for the Kansan Age, the second glacial episode of the Pleistocene. The equivalence of deposits classed as Kansas till in Kansas with similarly named deposits in Nebraska and Iowa has been demonstrated by (1) tracing and (2) stratigraphic sequence. This stratigraphic unit was first traced southward from the Union County, Iowa, localities by Bain (1897) and has been traced extensively in Iowa (Kay and Apfel, 1929), Nebraska (Lugn, 1935; Condra and Reed, 1950), and by test drilling in northeastern Kansas (Frye and Walters, 1950). The second line of evidence is that those workers in Nebraska and Iowa have demonstrated, by delineating the southern limits of younger glacial deposits, that only the Nebraskan and Kansan glaciers could have extended as far south as Kansas. Therefore the conclusive evidence in Doniphan County, Kansas (the Iowa Point section, Frye and A. B. Leonard, 1949) of two tills separated by a significant weathering interval requires the correlation of the upper of these two tills with the Kansas till at localities to the north. Although molluscan faunas have not been obtained from Kansas till in the area north and east of Kansas, large faunas have been obtained from water-deposited sediments, locally associated with volcanic ash, framed between tills, and molluscan fossils have been obtained from the basal part of the Kansas till in Kansas.

The precise placement of various deposits of Kansas till within the span of the Kansan Age is difficult. Till, as a direct deposit from glacial ice, obviously cannot be laid down at a given spot before the ice front has reached it; also, as the ice front retreats, if it remains active, it will continue the deposition of till. Therefore the deposits of the Atchison formation (pro-Kansan) in Marshall County and along the central Kaw Valley may be wholly younger than type Atchison and the same age as the Kansas till that overlies type Atchison. Also, the earliest outwash deposits from the retreating Kansan glacier near its maximum extent are older than till made at the retreating ice front as it withdrew from Kansas.

Definition and subdivisions--The Meade formation was described in 1941 by Frye and Hibbard (p. 411) and the type locality specified as the Pleistocene strata overlying the Ogallala formation in sec. 21, T. 33 S., R. 28 W., Meade County, Kansas (section published by Frye, 1942, p. 98). This locality has been restudied and a measured section is given below. The name "Meade gravels" was proposed by Cragin in 1896 (p. 52) for fossiliferous gravels in central Meade County. Although the unit was inadequately defined, a type locality was not clearly specified and a measured section was not given, it is judged that Cragin's Meade gravels correspond to the Grand Island member of the Meade formation of present classification of the Kansas Geological Survey because Cragin stated that his "Meade gravels" were overlain by the Pearlette volcanic ash, with which they were frequently gradational, and that the gravels were equivalent to the Tule division of Cummings (in Texas). Only the Grand Island member satisfies these requirements. In 1949 Hibbard (1949b, p. 70) proposed that the beds at the type locality of the Meade formation be renamed the "Crooked Creek formation" and that the name "Meade formation" (Hibbard, 1949b, p. 66) be applied to deposits in the NW sec. 13, T. 30 S., R. 23 W., Clark County (about 35 miles east-northeast from Meade), and to beds exposed along Spring Creek Valley west of Meade, classed here as Blanco formation.

In 1941 (Frye and Hibbard, p. 411) deposits younger than those exposed at the type section were included within the Meade formation, an expedient which was defended (Frye, 1942) as an aid to mapping on conventional map scales. Frye, Swineford, and Leonard (1948, p. 521) restricted the span of the Meade formation to that represented by the beds at the type section. This restricted definition of the Meade has been accepted by the Kansas Geological Survey and is standard usage in all official reports (Moore and others, 1951, pp. 14-16). The name is used throughout Kansas and includes retreatal Kansan outwash in the glaciated area. Deposits equivalent to the Meade formation have been correlated from western Texas across western Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, and into southeastern South Dakota and western Iowa (Frye, Swineford, and Leonard, 1948).

| Meade formation, type locality, in the SE NE NE sec. 21, T. 33 S., R. 28 W., Meade County, Kansas, Measured in canyons south of State Highway 98 and east of Crooked Creek, August 9,1951. | Thickness, feet |

||

| QUATERNARY--Pleistocene | |||

| Meade formation (Kansan Stage) | |||

| Sappa member | |||

| 13. Sand with some silt, pale yellowish-brown (10YR6/2) to moderate yellow. Abundant large hard caliche nodules. Exposed to top of east valley wall of Crooked Creek at upland level | 5.0 | ||

| 12. Sand, fine, and silt, massive, pale yellowish-brown (10YR6/2) to moderate yellowish-brown (10YR5/4). Caliche throughout, more abundant at top, nodules range up to 1 foot in diameter | 7.0 | ||

| 11. Silt and fine sand, pale olive (10Y6/2), caliche concentration throughout | 6.0 | ||

| 10. Silt and fine sand, pale yellowish-brown (10YR6/2) with scattered caliche nodules. Stratigraphic position of the Borchers vertebrate fauna | 2.0 | ||

| 9. Silt and clay, pale olive (10Y6/2) to yellowish-gray (10Y7/2); a few caliche nodules near top | 5.5 | ||

| 8. Volcanic ash, Pearlette bed, weathered, yellowish-gray (5Y7/2) with yellowish mottling. In adjacent canyons the ash is fresh and displays the petrographic characters typical of the Pearlette bed. In commercial ash mines both north and south of this locality the Cudahy vertebrate fauna and a large molluscan fauna have been obtained from the beds immediately below the ash; at some localities fossil snail shells occur within the ash | 6.0 | ||

| 7. Sand with some silt, massive and free of caliche, pale olive (10Y6/2) slightly mottled with yellow | 3.5 | ||

| 6. Silt, sand, and clay, grayish-olive (10Y4/2), mottled with yellowish; caliche nodules disseminated throughout and coalesced into a cemented zone at top | 5.0 | ||

| 5. Silt, sandy, and clay, dusky-yellow (5Y6/4) with disseminated caliche | 1.5 | ||

| 4. Silt, with some sand and clay, light olive-gray (5Y3/2); disseminated caliche nodules | 2.5 | ||

| 3. Silt with some sand, clay, and gravel, moderate reddish-brown (5YR4/4), poorly sorted. Contains pebbles up to 1.5 inches in diameter; nodular caliche gives a mottled appearance on weathered surface | 8.0 | ||

| Grand Island member | |||

| 2. Sand and gravel, with some fine sand and silt; gravel arkosic, tan, grades into well-sorted sand and gravel at the base; large pebbles exceed 2 inches in diameter; small scattered caliche nodules in the upper part. Erosional unconformity at base | 10.4 | ||

| Total thickness of Meade formation | 62.4 | ||

| TERTIARY--Pliocene | |||

| Ogallala formation | |||

| 1. Silt and sand, pinkish-tan, unevenly cemented with calcium carbonate and containing large caliche nodules; contains a a few Biorbia fossilia seeds. Lower part is cross-bedded sand, gravel, and cobbles exposed to the level of Crooked Creek. Test hole penetrated Permian redbeds 17 feet below base of exposure on east side of Crooked Creek. | |||

| Total thickness of Ogallala formation | 84.0 | ||

In Kansas and generally throughout the Great Plains and central Missouri Valley region, deposits correlated with the Meade formation are coarse-textured in the lower part and grade upward into finer textured elastics. Lenticular deposits of volcanic ash occur within the formation at many localities. Although the strata comprising the Meade formation are conformable throughout, these contrasting lithologies merit recognition as named subdivisions. In Nebraska, equivalent deposits are classed as Grand Island and Sappa formations and these names have been adopted in Kansas to designate members within the Meade formation.

The Grand Island formation in Nebraska was described by Lugn in 1935, and named for a type section in the Platte River bluffs east of Hamilton bridge and in the Platte River Valley southeast of Grand Island, Hall County, Nebraska (Lugn, 1935, pp. 106,107). Lugn (1935, p. 103) stated concerning the Grand Island: "It is the inwash-outwash equivalent of the Kansan till and the early Kansan inter-till sands and gravels of eastern Nebraska. It ranges in thickness from 30 to perhaps 150 feet, but averages about 75 feet."

The Sappa formation in Nebraska was named by Condra and Reed (1950, p. 22) from exposures in the abandoned volcanic ash mine of the Cudahy Packing Company near Orleans in Sappa Township, Harlan County, Nebraska. The name was proposed as a direct replacement for the name Upland formation of Lugn (1935, p. 119), which prior to 1948 was in general use to designate these deposits. The type locality of Lugn's Upland formation is along West Branch Thompson Creek about 2 1/2 miles west of the town of Upland in Franklin County, Nebraska. Lugn (1935, p. 119) considered the Upland to be Yarmouthian in age but Condra and Reed (1950, p. 12) correlate the Sappa formation as late Kansan. The Sappa member was described in Kansas by Frye, Swineford, and Leonard (1948).

Plate 8--Pearlette volcanic ash. A, Pit in Pearlette ash in the NE SW sec. 21, T. 13 S., R. 26 W., Gove County. Beds immediately below the ash yielded large molluscan fauna (Norman Plummer, 1948). B, Pit in Pearlette ash in the NW sec. 34, T. 8 S., R. 23 W., Sheridan County. Maximum thickness of ash is 16 feet (1951). C, Pearlette ash in road cut in the NW SW sec. 27, T. 13 S., R. 10 W., Lincoln County, 7 feet of ash exposed. Large molluscan fauna (Wilson Valley faunule) and fossil vertebrates were collected from beds at the base (1951).

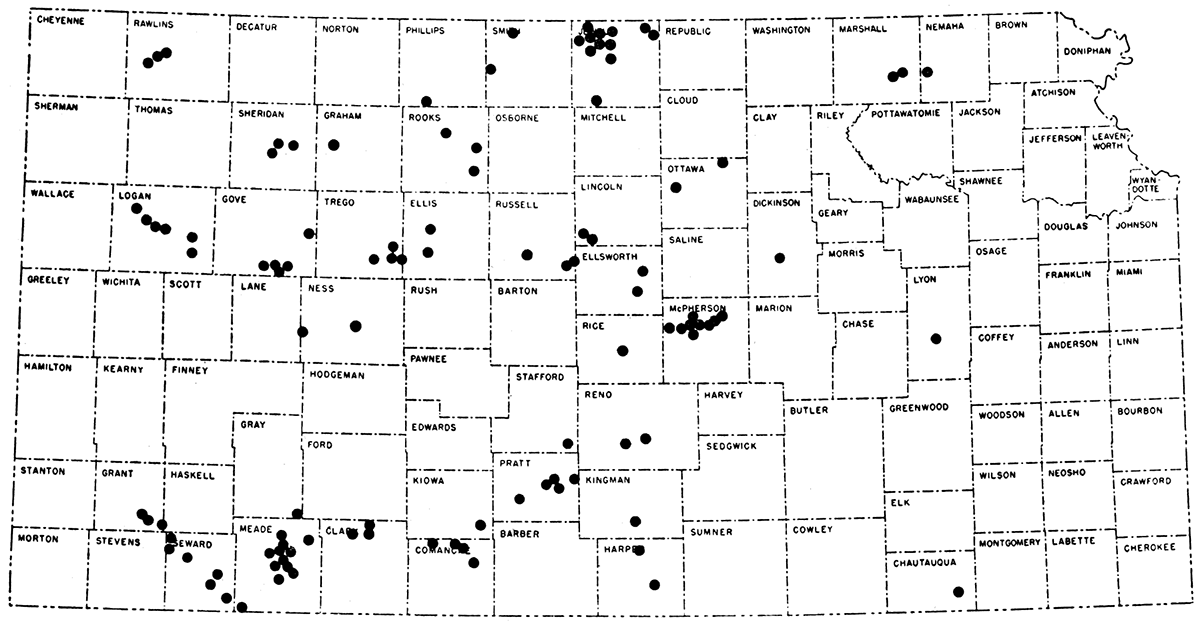

The Pearlette volcanic ash bed (Pl. 8) occurs as lentils within the Sappa member. The name Pearlette was proposed by Cragin in 1896 from outcrops in the vicinity of the long abandoned Pearlette post office, Meade County, Kansas. The Pearlette bed (Fig. 3) is present discontinuously in Sappa member, Tule formation, and equivalent beds in Texas, Colorado, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Missouri, Iowa, and South Dakota. The ash is judged to have been derived from a source in north-central New Mexico (Swineford, 1949). Its petrographic character has been studied (Swineford and Frye, 1946; Carey and others, 1952) and it has been correlated throughout most of the area of its occurrence (Frye, Swineford, and Leonard, 1948). The distinctive petrographic characters of the Pearlette volcanic ash have been described as follows (Frye, Swineford, and Leonard, 1948, p. 513):

- The color includes certain light shades of orange-yellow, which are not characteristic of fresh ash described from the Pliocene (Calvert mine).

- The refractive index is consistently 1.499-1.501.

- The shape of the shards is characteristically sharply curved, with thickened glass at the bubble junctures, which are commonly curved and branching at wide angles. Fibrous shards are present in all samples.

- Many shards have groups or clusters of elongate vesicles which are seldom found in ash of Pliocene age.

- The percentage of iron oxide is less than 2 as shown by eight of nine chemical analyses, with a range from 1.43 to 2.07 per cent. . . .

- The specific gravity ranges from 2.21 to 2.32. . . .

Figure 3--Map showing distribution in Kansas of the principal deposits of Pearlette volcanic ash. All known deposits of volcanic ash in Kansas are listed by Carey and others (1952).

Character and distribution--In Kansas the Meade formation occurs extensively as abandoned valley fillings in the southwestern and central areas, as chert gravel terraces in the east-central area, and as outwash terrace deposits along the Kansas, Blue, Little Blue, and other river valleys in the northeastern glaciated area. In north-central and northwestern Kansas the Meade formation occurs as discontinuous terrace remnants along several valleys but is quantitatively of minor importance (Pl. 1).

In the east-central area the Meade formation has been studied in detail only along the Neosho-Cottonwood Valley. In this important valley, Meade formation constitutes much of the fill under the Emporia terrace (Moore, Jewett, and O'Connor, 1951) which occurs almost continuously from Chase County southward to the Oklahoma state line. Along this valley the Emporia terrace surface has a height of 25 to 40 feet above the adjacent flood plain, but 40 feet is probably the more typical height. The formation here consists of chert gravels with some sand and beds of silt in the lower part (Pl. 9B) overlain by silts and sandy silts. At several places, for example the cuts along U.S. 50S west of Emporia, a well-developed soil overlain by a few feet of Peoria loess occurs in the upper part of the terrace silts. A distinctive lithologic element is the presence of Pearlette volcanic ash (Frye, Swineford, and Leonard, 1948) in the terrace deposits within the city limits of Emporia. In the east-central part of the State the Meade formation, except for a small percentage of limestone pebbles in the lower part and a lower percentage of red clay matrix in the upper part, is lithologically indistinguishable from the older chert gravel terrace deposits. It is recognized and traced by its physiographic position and dated by the contained Pearlette volcanic ash bed.

Plate 9--Terraces and terrace deposits. A, Meade formation, Grand Island member, overlain by Sappa member including Pearlette volcanic ash, with thin veneer of Crete gravels forming surface of Pfeifer terrace of Smoky Hill River Valley. Meade formation rests on Carlile shale (Cretaceous). NE SE sec. 28, T. 14 S., R. 21 W., Trego County (1950). B, Chert gravel assigned to Grand Island member, Meade formation, in pit in the Emporia terrace of Cottonwood River Valley. Terrace surface is approximately 35 feet above the level of adjacent flood plain. Cen. sec. 10, T. 19 S., R. 9 E., Chase County (1950). C, Scarp of Kirwin terrace on north side of Solomon River Valley; SE sec. 6, T. 6 S., R. 12 W., Osborne County. The Kirwin terrace is comparable to other alluvial terraces (Almena, Newman) of northern Kansas, and the sediments comprising its upper part are latest Wisconsinan to Recent in age (1950).

In other valleys of eastern Kansas chert gravel terraces in a comparable topographic position may be late Kansan in age and equivalent to the Emporia terrace. In Elk River Valley terrace remnants 20 to 30 feet above flood plain have been observed at Langdon and Howard in Elk County. Other possible equivalents were examined at Cen. E. line sec. 15, T. 20 S., R. 17 E. and in the SW sec. 1, T. 22 S., R. 11 E., Greenwood County, where the gravels are relatively near their source and angular pebbles predominate.

In northeastern Kansas the Grand Island gravels present a striking contrast in lithology with the chert gravels of the Emporia terrace. In the northeastern area the Grand Island gravels are outwash valley train deposits derived from the retreating Kansan glacier. They consist of cobbles (up to 18 inches in diameter) of limestone, igneous and dark metamorphic rocks, and pink quartzite (Pl. 6A, 6C). In the central Kansas River Valley where the Meade formation underlies the surface of the extensive dissected remnants of the Menoken terrace (Davis and Carlson, 1952) the relation of the Grand Island gravels to Kansas till is clearly demonstrated by the interfingering of till with the lower part of the gravels (for example, SW sec. 9, T. 11 S., R. 15 E., Shawnee County). This terrace, where it has been studied eastward from Topeka, stands approximately 80 feet above Kansas River flood plain and has a bedrock floor approximately 20 feet above the flood plain. A terrace equivalent to the Menoken has not been recognized in the Missouri River Valley of northeastern Kansas.

Grand Island outwash gravels are extensive and well exposed along the valleys of the Big and Little Blue Rivers and Mill Creek in Marshall and Washington counties. The earliest outwash deposition in this region is judged to have occurred when the Kansan glacier stood across the Big Blue River Valley. This is indicated by the occurrence of coarse gravels containing quartzite and other glacial rock types on the uplands west of the valley (SW SE sec. 25, T. 3 S., R, 5 E.; NW NW sec. 16, T. 4 S., R. 4 E., Washington County) and along Mill Creek Valley (pits southeast of the City of Washington). The topographic position of these deposits is markedly higher than the prominent outwash terrace along the valleys of Little and Big Blue Rivers which represent a later phase of Kansas outwash after the glacier had retreated from its maximum extent. The Grand Island outwash gravels along these present valleys are relatively well sorted, contain boulders (Pl. 6C) in the lower part but grade upward through well-sorted sand and gravel to a silty sand zone at the top, and attain a thickness of more than 50 feet. These gravels are well exposed in pits at the following localities: SW SE sec. 16, T. 3 S., R. 7 E.; SE cor. sec. 16, T. 4 S., R. 7 E.; NE NW sec. 30, T. 4 S., R. 7 E., Marshall County; NE cor. sec. 18, T. 3 S., R. 5 E., Washington County.

West of Washington County in northern Kansas, Kansan outwash (Meade formation) fills an abandoned valley that enters the Republican River Valley in northern Republic County, and some deposits of Meade formation in adjacent Jewell County may be outwash that was carried across the site of the present Republican Valley. The filling of the abandoned valley in northern Republic County was formerly called the Belleville formation (Wing, 1930; Fishel, 1948). Although it is probable that this outwash spillway from the Kansan ice front extended down the Republican River Valley, the deposits have not been traced through this area.

Within the area thickly mantled with Kansas till, few exposures of outwash gravels have been observed. Outwash deposits have been studied along the valley of Vermillion River, particularly west of Frankfort (Marshall County) where Pearlette volcanic ash occurs in the upper (fine sand and silt) part of the deposit, and in road cuts and a small pit in the NW sec. 31, T. 2 S., R. 13 E., Nemaha County.

Westward into central Kansas along the Kansas-Smoky Hill Valley, evidence concerning the Grand Island gravels is fragmentary. Southwest of Junction City sand and gravel with a lithology consistent with outwash rests on relatively high bedrock at a position only slightly below the upland level. As these sands and gravels on the north side of the valley are at a markedly higher position than the top of a terrace remnant, which is Illinoian in age, on the south side of the valley, they are judged to be Kansan outwash deposited by a westward-flowing drainageway at the time of maximum extent of the Kansan glacier. At the time of maximum glacial advance all possible courses to the east were blocked by ice, and as deposits along all valleys south of the present Kansas River divide and east of the Flint Hills crest contain deposits which conclusively deny the presence of outwash, glacial drainage, at least for a time, must have gone southwest and south through then existing valleys in central Kansas.

The approximate position of the floors of late Kansan valleys in the area south of Abilene, Dickinson County, is indicated by a small terrace remnant along Turkey Creek Valley (SW sec. 35, T. 14 S., R. 2 E.). Here Pearlette volcanic ash and a large snail fauna in the upper part of gravels and sand rest on bedrock significantly above the adjacent low terrace. As this drainage is from. the south, the gravels consist predominantly of Permian and Cretaceous rocks and do not reflect an outwash source, even though the depositing stream joined an outwash-carrying valley. Sands and gravels that occur in a comparable terrace position, masked partly by sand dunes, on the north side of Smoky Hill Valley in this area may be Kansan outwash (Grand Island member).

In contrast to the fragmentary record southwestward into the Salina area, the region to the south and west in central Kansas contains extensive deposits of Meade formation. These deposits occur principally as the fillings of former major valleys abandoned in post-Kansan time, and as dissected high-level valley fillings now under the surface of a prominent terrace along Smoky Hill Valley westward from Marquette. One of the largest of these filled abandoned valleys, called McPherson valley, extends southward under the present Smoky Hill-Arkansas divide through western McPherson County, Harvey and Reno counties, into Sedgwick County. The character of this valley and its contained deposits is known from the records of more than 100 test holes (Lohman and Frye, 1940; Williams and Lohman, 1949) and from the exposures of deposits constituting the fill at their dissected north end in west-central McPherson County. This valley carried southward some outwash from the northeast at the time of the Kansan glacial maximum as well as the drainage of the Smoky Hill basin from the west for a much longer time. The Meade formation in this valley (formerly classed within the broadly inclusive McPherson formation) consists of gravel and sand, attaining a maximum thickness of 100 feet, which grades upward into silt and sand containing Pearlette volcanic ash (Carey and others, 1952) in several exposures.

Deposits of the Meade formation extend southward through McPherson valley, under the Hutchinson dune tract, into the valley of Arkansas River (Pl. 2) where they join (Pl. 1) comparable deposits of Meade formation that constitute the fill of buried valleys extending toward the west and northwest (Fent, 1950, 1950a; O.S. Fent, in preparation [Indicates study of geology and ground-water resources of Reno County in progress.]). As the McPherson valley carried the major drainage of the area southward, it was cut below the level of the adjacent Nebraskan Blanco deposits and the Pliocene Ogallala formation (called Delmore formation by Williams and Lohman, 1949) in northern McPherson County. Southward along Arkansas Valley from the junction of McPherson valley with the system of valleys containing Fent's (1950) Chase channel, the topographic position of the Meade formation progressively rises to a high terrace position just north of Ninnescah River Valley west of Arkansas River. Here (sec. 27, T. 30 S., R. 1 E., Sumner County) the Kansan terrace is only slightly below the upland to the northwest which is veneered with Blanco formation.

South of Ninnescah River Valley the Meade formation caps the uplands east of Arkansas Valley. These deposits are largely assignable to the Grand Island member as they consist of gravel and sand (SW NW sec. 36, T. 31 S., R. 1 E.; W2 sec. 1, T. 32 S., R. 1 E.; SE sec. 21, T. 33 S., R. 1 E.; NE NE sec. 36, T. 34 S., R. 2 E., Sumner County) and where exposed in a small abandoned pit in the SW NW sec. 25, T. 34 S., R. 2 E., Sumner County, a heavy soil profile with a reddish B horizon is developed in these slightly arkosic gravels.

On the east side of Arkansas Valley gravels occur in the Cen. W2 sec. 21, T. 34 S., R. 5 E,, Cowley County, at approximately the same topographic position with respect to the Arkansas Valley but markedly below the Flint Hills upland several miles farther east. At this locality the lithology of the gravels is typical of those of the Flint Hills. These gravels, containing rocks characteristic of the Permian bedrock in the area north-northeast from where they occur, rest on the eroded surface of the Fort Riley limestone. In spite of their strong lithologic contrast with the gravels west of the Arkansas Valley they are classed as Meade formation because of the similarity of topographic position and because the gravels on the west side of the valley contain a small but persistent percentage of Permian chert pebbles requiring a source east of the present position of Arkansas River Valley. These facts, and the regional relationships, lead to the judgment that the principal southward drainageway across this area in late Kansan time was located west of the present Arkansas River Valley and that it had important tributaries from the northeast which drained the west flank of the Flint Hills uplands area.

In the region of central Kansas along the Arkansas River Valley and in the area to the south included within the great bend of the Arkansas, the Meade formation has its most extensive development in the State. In this area it has been studied by the use of several hundred test holes and logs in Rice (Fent, 1950), Barton and Stafford (Latta, 1950), Reno (O. S. Fent, in preparation), Pratt (D. W. Berry, in preparation [Indicates study of geology and ground-water resources of Pratt County in progress.]), and Pawnee and Edwards (McLaughlin, 1949) counties, and its relation to early Pleistocene filled valleys has been discussed by Fent (1950a). Although the Meade formation is generally not well exposed in this area, several good exposures of Pearlette volcanic ash and associated molluscan faunas are afforded by small pits in southwestern Reno County (SE cor. NE sec. 1, T. 25 S., R. 7 W.; SW SE sec. 6, T. 25 S., R. 7 W.). Pearlette volcanic ash has been studied at several localities in Pratt and Kingman counties (Carey and others, 1952) and has been penetrated in several test holes drilled in Rice County (Fent, 1950). In this area the Meade formation is composed largely of sand and gravel (Grand Island member); it occurs as the lower or intermediate part of the filling of valleys cut in the bedrock (Pls. 1, 2) and in much of the area is overlain by the Illinoian Crete gravels and Wisconsinan dune sand and alluvium.

In the northern part of the Great Bend region the Grand Island gravel member reflects a source in adjacent central Kansas to the northwest. The Grand Island is more arkosic than the older Blanco formation gravels, indicating that during late Kansan time the Ogallala formation was being eroded throughout a more extensive region. In the southern part of this area (Pratt County) the Grand Island has a larger percentage of granitic pebbles than in the north, its lithology approaching that of the late Pleistocene alluvium of the Arkansas River.

In the northern two tiers of Kansas counties west of the influence of outwash from continental glaciation, the Meade formation is known from scattered small deposits. These few localities establish that most of the major valleys of this area formerly contained late Kansan alluvial terraces that have subsequently been largely removed by erosion. In Prairie Dog Creek Valley a remnant of Grand Island gravels, containing a diagnostic molluscan fauna, occurs within the anomalous loop of that stream northwest of Woodruff, Phillips County, and is well exposed in a cut of the C. B. and Q. Railroad (erroneously identified by Frye and A. R. Leonard, 1949, as Crete). Fossiliferous Sappa silts overlying Grand Island gravels are also exposed in a dissected terrace remnant south of Long Island, Phillips County, and at both of these localities the deposits are distinctly higher in the topography than the adjacent Crete sand and gravel member of the Sanborn formation. Fossiliferous Meade formation occurs at several localities along the North Fork Solomon River in south-central Norton County, and Grand Island gravels resting on Cretaceous Niobrara chalk are well exposed in a cut along Highway U.S. 283 in the NW SW sec. 19, T. 5 S., R. 22 W. Here, also, this dissected remnant of late Kansan terrace stands topographically higher than adjacent deposits of Illinoian age, but its position indicates that the valley floor had been cut to a level slightly below the base of the adjacent Ogallala formation before deposition of the Meade formation. Perhaps the relation of Kansan, Illinoian, and Wisconsinan terraces along the Solomon River system is most clearly discernible in the area west of Portis, Osborne County (A. R. Leonard, 1952). Here the fossiliferous Sappa and Grand Island members of the Meade formation are well exposed in a pit in the NW cor. sec. 11, T. 6 S., R. 13 W., in a large remnant of the high level (Kansan) terrace and extensive intermediate (Illinoian) and Kirwin (Wisconsinan) terraces occur in the same segment of the valley. The same general relation of terraces is demonstrated westward along South Fork Solomon Valley by a terrace remnant in the S2 sec. 12, T. 8 S., R. 27 W., Sheridan County, where two small pits expose Grand Island gravels (on Ogallala formation) overlain by Sappa silts containing Pearlette volcanic ash, and an abandoned pit in Pearlette volcanic ash in the NW sec. 34, T. 8 S., R. 28 W., Sheridan County.

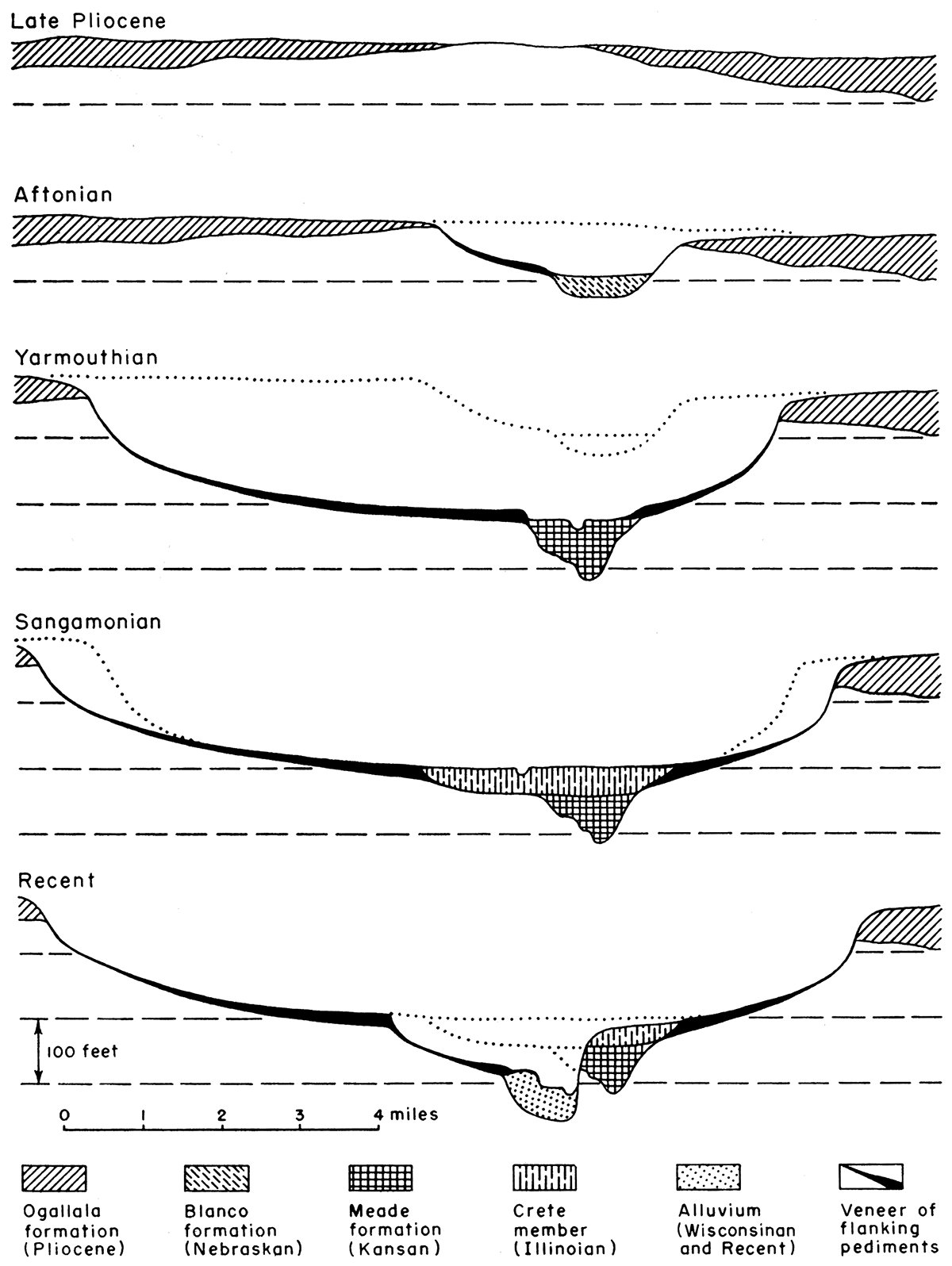

In north-central and northwestern Kansas along the Solomon River system and the streams tributary from the south to Republican River, the Pleistocene deposits, although fragmentary, clearly demonstrate a physiographic terrace sequence--the older deposits occur on higher terraces and the younger deposits on progressively lower terraces. This relation is in strong contrast to the situation in part of central Kansas where, although incised deeply below the Pliocene Ogallala, progressively younger Pleistocene deposits overlie older units in the filled bedrock valleys in a normal stratigraphic sequence. The Smoky Hill River system, which stands between these areas geographically, is also intermediate in physiographic relations. In this system there is record of (1) moderate incision below the Pliocene surface followed by late Nebraskan alluviation; (2) deep incision, almost to the level of the present flood plain, followed by late Kansan alluviation; (3) Illinoian alluviation across the top of late Kansan deposits with virtually no downcutting; (4) deep incision in early Wisconsinan time to the bedrock floor of the present valley followed by alluviation, and then minor cut and fill during Recent time (Fig. 4). The complex Kansan-Illinoian terrace has been traced almost continuously from western Logan County to eastern Ellsworth County (Frye, Leonard, and Hibbard, 1943; A. R. Leonard and D. W. Berry, in preparation [Indicates study of the geology and ground-water resources of the central Smoky Hill River Valley in mils County and southeastern Trego County, Kansas, in progress.]), and into the dissected deposits at the north end of the abandoned McPherson valley in northwestern McPherson County (Pl. 1).

Figure 4--Idealized cross sections showing the development of the Smoky Hill River Valley during Pleistocene time. Data are from western Kansas and the sections are particularly generalized from south-central Gove County, Wisconsinan and Recent dissection by minor tributaries is ignored.

The gradient of the surface of the Kansan-Illinoian terrace of the Smoky Hill converges with and diverges from the gradient of the late Wisconsinan terrace and the flood plain in response to bedrock control. The Ft. Hays and Greenhorn limestones are relatively resistant units and as valley cutting has proceeded the points of valley crossing of these units have migrated upstream and therefore interruptions in the stream profile have migrated upstream.

In the western part of the State the Kansan Smoky Hill Valley was relatively narrow and the Meade formation is confined to a sharply constricted bedrock trough. In contrast, the overlying Crete (Illinoian) gravels are more extensive laterally and the terrace surface marked by their top grades into the surface of the flanking pediments cut on the Cretaceous bedrock. The stratigraphic sequence under this terrace surface is shown by the following measured section from Gove County.

| Section of Meade formation and Crete member, Sanborn formation, exposed in side of tributary valley, south of Smoky Hill River in the NW NE sec. 26, T. 15 S., R. 29 W., Gove County. | Thickness, feet |

||

| QUATERNARY--Pleistocene | |||

| Sanborn formation--Crete member (Illinoian Stage) | |||

| 7. Sand and gravel, granitic, well-sorted, contains pebbles up to 1.5 inches in diameter. Unconformable on Meade formation and adjacent Niobrara chalk | 6.6 | ||

| Meade formation (Kansan Stage) | |||

| Sappa member | |||

| 6. Silt, massive, strongly calcareous, light-gray, contains disseminated sand grains and pebbles. Superficially resembles weathered chalk | 10.7 | ||

| 5. Silt, even-bedded, with some sand. Lenses of Pearlette volcanic ash ranging in thickness up to 1.5 feet. Lenses of fine even-bedded sand | 8.0 | ||

| Grand Island member | |||

| 4. Sand and gravel, fine to medium | 2.6 | ||

| 3. Silt with some sand, compact, light-gray and tan, weathered surface superficially resembles chalk | 1.5 | ||

| 2. Sand and gravel, granitic and local Cretaceous and Ogallala pebbles. Pebbles range up to 3 inches in maximum diameter. Irregular unconformable surface at base | 5.2 | ||

| Total thickness of Pleistocene deposits | 34.6 | ||

| CRETACEOUS--Gulfian | |||

| Niobrara formation--Smoky Hill chalk member | |||

| 1. Shale, chalky, thin-bedded, blue-gray and tan. | |||

A few miles eastward along this terrace in Gove County a gravel pit exposes the thick channel gravel phase of the Grand Island overlain by discontinuous eroded remnants of fossiliferous Sappa member and thick coarse channel gravels of the Crete member of the Sanborn formation (Cen. N. line sec. 29, T. 15 S., R. 28 W., Gove County). In this area, where the unconformity at the base of the Crete is cut entirely through the Sappa member, the Crete gravels are indistinguishable lithologically from the Grand Island gravels.

Farther east along Smoky Hill Valley excellent exposures of the Meade and Crete underlying this terrace surface occur in eastern Trego County. Here the Meade formation rests on Cretaceous Carlile shale, contains Pearlette volcanic ash (Pl. 9A), and is overlain by thick deposits of coarse gravels of the Crete member. In this area detailed test drilling (A. R. Leonard and D. W. Berry, in preparation) has shown the character of the constricted deep Kansan channel filled with Meade formation and overlain by the broader fill of Crete gravels.

Eastward into Russell County the Kansan-Illinoian terrace becomes progressively wider, attaining a maximum width of nearly 5 miles, and the flanking pediments become less distinct. In this segment of the valley several good exposures show the Meade and Crete near the mouths of entering tributary valleys where the deposits under the terrace surface are thinner than in the central part of the valley and the lithology of these units reflects a local source (SW sec. 35, T. 14 S., R. 11 W.). A measured section from this area is given below.

| Kansan and Illinoian deposits under terrace of Smoky Hill Valley, SW sec. 35, T. 14 S., R. 11 W., Russell County. | Thickness, feet |

||

| QUATERNARY--Pleistocene | |||

| Sanborn formation--Crete member (Illinoian Stage) | |||

| 6. Upper part of interval covered, may contain colluvium and some Peoria loess. Lower part is cross-bedded irregularly sorted sand, gravel, and silt and contains caliche nodules near surface. Gravel contains pebbles of Cretaceous chalk | 20.0 | ||

| Meade formation (Kansan Stage) | |||

| Sappa member | |||

| 5. Sand, fine, and silt; massive in upper part, thin-bedded in lower part with lenses of sand, tan and buff. Contains fragments of fossil vertebrates and snails | 10.6 | ||

| 4. Pearlette volcanic ash; thickens to the west | 0.2 | ||

| 3. Silt and fine sand, gray to greenish-gray, with thin beds of sandy clay, some pebbles in lower part. Terrestrial snails occur in lower 5.5 feet, aquatic snails in upper 1 foot below volcanic ash (Tobin faunule) | 6.5 | ||

| Grand Island member | |||

| 2. Gravel and sand, cross-bedded, interbedded with thin beds of silt. Gravel predominantly of Cretaceous chalk and sandstone with some granitic pebbles. Cobbles of chalk and sandstone as much as 0.7 foot in maximum diameter | 3.9 | ||

| Total thickness of Pleistocene deposits measured | 41.2 | ||

| CRETACEOUS--Gulfian | |||

| Dakota formation | |||

| 1. Shale, siltstone, clay, and sandstone, red, brown, tan, and gray; to level of flood plain of Smoky Hill River | 40.0 | ||

During Kansan time a major tributary from the northwest joined the early Smoky Hill Valley in western Ellsworth County. The lower course of this tributary is recorded by abandoned "Wilson valley," and its contained deposits, which extend across the present divide between the Saline and Smoky Hill Rivers (Frye, Leonard, and Hibbard, 1943; Frye, 1945b). The surface of the floor of Wilson valley is accordant and continuous with the surface of the Kansan-Illinoian terrace of the Smoky Hill Valley, but to the north the dissected valley floor stands more than 150 feet above the channel of Saline River. The deposits under the floor of this abandoned valley consist largely of Meade formation containing Pearlette volcanic ash (Pl. 8C) and associated molluscan fauna. The lack of Crete gravels--in contrast to the Smoky Hill Valley--indicates that Wilson valley was abandoned after Kansan time and prior to Illinoian time. Thin Loveland silt containing Sangamon soil overlain by thin Peoria loess locally mantles the Meade formation. The maximum thickness of Pleistocene deposits under the floor of Wilson valley, indicated by outcrops and a line of test holes along the Ellsworth-Lincoln County line (Berry, 1952) is about 75 feet.

The foregoing data show that the Kansan deposits of the Smoky Hill Valley, abandoned Wilson valley, abandoned McPherson valley, and south-central Kansas including the Great Bend area and Rice County, all fit an integrated stream pattern and are all genetically related. The contrasting topographic positions of the Meade formation in various parts of this region are due to post-Kansan drainage changes.

In southwestern Kansas the Meade formation is not present or is poorly exposed except along the valley of Crooked Creek in central Meade County, the Cimarron Valley, and Bluff Valley in northwestern Clark County. In these areas the formation and its contained Pearlette volcanic ash are well exposed and have been studied intensively (Frye and Hibbard, 1941; Frye, 1942; Hibbard, 1944; McLaughlin, 1946; Byrne and McLaughlin, 1948; Frye, Swineford, and Leonard, 1948; A. B. Leonard, 1950; Carey and others, 1952). The type locality of the formation is in this area. It consists of exposures in the east valley wall of Crooked Creek south of the City of Meade; more than 30 localities of Pearlette volcanic ash are known in the southwestern area (Carey and others, 1952); abundant molluscan faunas have been described (A. B. Leonard, 1950); and the bulk of the fossil vertebrates known from the Kansan deposits of Kansas have been collected in this area (Hibbard, 1944, 1949a, 1949b).

The lithology of the Meade formation of central Meade County contrasts with the lithology of the formation in the central Kansas region in that the Sappa member constitutes a much larger part of the total volume of the unit, and along the trend of the Crooked Creek fault, suggests deposition in slack water. The Grand Island member, although containing similar rock types, is generally finer. However, some exposures along Cimarron River Valley (particularly near Arkalon in Seward County) display thick coarse gravels in the Grand Island member.

Age and correlation--Correlation of beds equivalent to the Sappa member of the Meade formation has been established with certainty through a region extending from west-central Texas across western Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska and into southeastern South Dakota and western Iowa. This has been possible largely due to the association in these deposits of a petrographically distinctive volcanic ash bed with a large and definitive molluscan fauna, although the more common techniques of tracing alluvial terraces and lithologic units and stratigraphic sequence were also used extensively.

For many years deposits of volcanic ash have been known to occur at several stratigraphic positions in the Miocene, Pliocene, and Pleistocene deposits of the central Great Plains region. Petrographic studies of ash from these several stratigraphic positions revealed that each fall possessed distinctive physical properties and therefore it became possible to identify the Pearlette bed from uncorrelated deposits (Swineford and Frye, 1946; Frye, Swineford, and Leonard, 1948). When a unique lithology such as this became combined with a molluscan faunal assemblage of more than 60 species containing first appearances, last appearances, and restricted species, a means was provided for making long-range correlations that could be extended with safety across major drainage divides and between deposits from different sources.

Not only has the Meade formation (Sappa member) been correlated with certainty across a region embracing parts of seven states, but also its stratigraphic framing is almost equally well established. In Kansas, Sappa member with Pearlette volcanic ash has been studied in Marshall and Nemaha counties where it occurs unconformably on Kansas till, and at many localities in central and western Kansas it occurs unconformably on Blanco formation. At several localities in the Missouri Valley area of Nebraska, Iowa, and South Dakota, deposits correlated with the Sappa member by Pearlette volcanic ash or molluscan fauna are judged to occur stratigraphically above Kansas till (Frye, Swineford, and Leonard, 1948). These data establish the Meade formation as post-Kansas till deposition. At several score localities in Kansas and also at a few localities northward from Kansas along the Missouri Valley, Sappa member is overlain uneonformably by Loveland loess (Illinoian) containing in its top the Sangamon soil. Also, near Santee and other localities in northeastern Nebraska the Sappa is overlain by Iowa till (Frye, Swineford, and Leonard, 1948). These data clearly frame the Meade formation between the times of maximum advance of the Kansan glacier and that of the Illinoian glacier but do not place it more precisely within this interval.

Placement of the Meade formation within this framed interval is judged to be possible from several other lines of evidence. (1) A small but diagnostic molluscan fauna has been collected from the base of the Kansas till at the Iowa Point section, Doniphan County, Kansas, and all species obtained are characteristic of the Sappa fauna. (2) An evaluation of the relationship of alluvial cut and fill to times of glacial advance (Frye, 1951) has been presented elsewhere in this report and indicates that this deposit is genetically related to the retreat of the Kansan glacier. (3) In the marginal area of the Kansan glacier, particularly the central Kaw Valley, Atchison formation, Kansas till, and Grand Island member form a conformable sequence, and in fact Grand Island gravels and Kansas till interfinger at a few places. (4) Yarmouth soil, with a degree of development comparable to Sangamon soil in the same area, and developed on Sappa silts is overlain by Loveland loess (Illinoian) at a few localities. These data demonstrate that the Grand Island member is retreatal outwash of the Kansan glacier, and in areas remote from glaciation equivalent in age to such outwash; and that the Sappa member (conformable and gradational with the Grand Island) is a continuation and later phase of this episode of alluviation, perhaps culminating at or slightly after the dissipation of the Kansan glacier. Therefore, the Grand Island is classed as late Kansan and the Sappa as latest Kansan and perhaps earliest Yarmouthian.

Prev Page--Stratigraphy--Nebraskan Stage || Next Page--Stratigraphy--Yarmouthian Stage

Kansas Geological Survey, Pleistocene Geology

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

Web version August 2005. Original publication date Nov. 1952.

URL=http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/Bulletins/99/05_strat2.html