Kansas Geological Survey, Bulletin 86, Part 1, originally published in 1950

Next--Deep-seated Solution

Originally published in 1950 as Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin 86, Part 1. This online version has been created because the published version is currently out of print. This is, in general, the original text as published in 1950. The information has not been updated.

Undrained depressions of various sizes and shapes are a characteristic minor element of Kansas Great Plains topography. A review of depressions in all parts of western Kansas indicates that several processes of origin are required to explain the many diversified features. They are classed in two general groups: (1) solution-subsidence depressions where the soluble rock may be salt, gypsum, chalk, or limestone, and (2) nonsolutional features produced by variously differential eolian deposition or erosion, compaction, silt infiltration, and animal action.

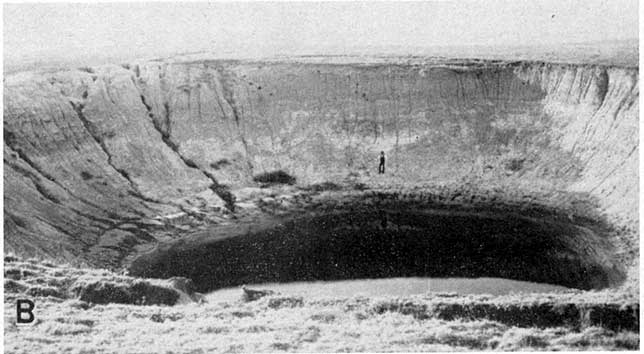

Undrained depressions of many sizes and shapes are characteristic of the topography of much of western Kansas (Schoewe, 1949, p. 314-324). In some areas they are quite closely spaced and their aggregate number is counted in thousands. The Colby quadrangle (Fig. 1) is typical of upland areas in the High Plains section. Here, the density of shallow depressions is indicated by the 748 intermittent lakes shown in the 252 square miles covered by the map. Great Plains depressions have diameters ranging from less than 10 feet to several miles, and their depths range from barely perceptible to more than 100 feet (Pls. 1, 2). Many are symmetrically circular or oval in plan, whereas others are elongate or irregular. The side slopes range from very gentle to precipitous cliffs (Pl. 2). A few depressions hold permanent bodies of water (Pls. 1, 2) but most of them contain lakes only after rains, if at all. They occur in rocks of Permian, Cretaceous, Pliocene, and Pleistocene (including Recent) age.

Figure 1--Drainage and intermittent ponds from the Colby 15-minute quadrangle, Thomas County, Kansas. Map by U.S. Geological Survey. Note the abundance of depressions, indicated by ponds, in the broad upland divide areas. These areas are underlain by about 30 feet of late Pleistocene loess 150 to 250 feet of Ogallala formation (Pliocene) and Pierre shale. A larger version of this figure is available.

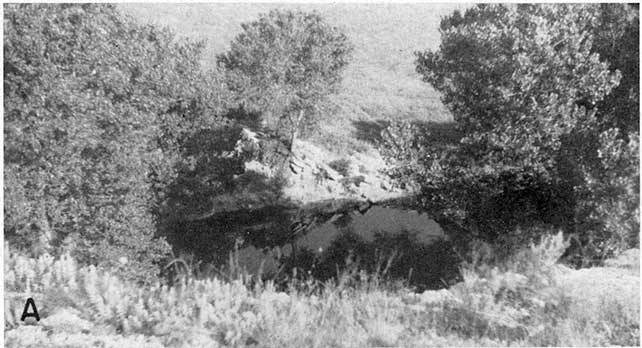

Plate 1--Solution-subsidence features. A, St. Jacob's well, west-central Clark County, Kansas, 1945. B, Meade "salt sink," 1½ miles south of Meade, central Meade County, Kansas. Photograph made in 1898 or 1899 by W. D. Johnson, U.S. Geol. Survey. This sink, which developed suddenly in 1879, is located just east of the Crooked Creek fault and is the result of deep-seated solution of Permian salt and gypsum. C, Meade "salt sink" as it appeared in 1939. Note erosion of sides and fill in sink bottom.

Plate 2--Great Plains depressions. A, Temporary pond in very shallow High Plains depression, north-central Thomas County, Kansas, 1943. B, Temporary lake in large High Plains depression, north of Sappa Creek, north of Levant, Thomas County, Kansas, 1943. C, Small High Plains depression on the Thomas-Logan County line (SE sec. 36, T. 10 S., R. 34 W.). This is one of the depressions where test drilling revealed no reflection of the feature in the Pierre shale surface at depth. 1943. D, Temporary lake in upland depression in sec. 25, T. 6 S., R. 35 W., Thomas County, Kansas, 1943. E, Rim of Ashland-Englewood basin showing Permian redbeds capped with Ogallala formation, north of Ashland, central Clark County, Kansas, 1940.

Undrained and formerly undrained depressions are noted in some of the early geological reports on the High Plains section, particularly Haworth (1896, 1897), Johnson (1901), and Darton (1905). They have been called "sinkholes, or swales, or lagoons, sometimes filled with water" (Haworth, 1897, p. 19). The abundance and varied nature of Kansas Great Plains depressions have invited several conflicting hypotheses of origin (Schoewe, 1949, p. 314-324). Also, they have been a subject of informal speculation and controversy among geologists concerned primarily with other aspects of Great Plains geology.

In connection with ground-water and stratigraphic studies during the past 12 years, I have had opportunity to examine many of the widely distributed depressions in the Kansas Great Plains region. Field observations and subsurface data have led to judgment that the depressions in central and western Kansas represent several modes of genesis, and that some indicate effects of more than one process.

The present paper undertakes to review pertinent features of these depressions bearing on their origin and the hypotheses of formation so far advocated, and to outline additional processes that may have played a part in their development. Schoewe (1949, p. 314-324) has recently described the appearance and distribution of variously sized basins in western Kansas. At least six distinct processes are judged to have played major or minor roles in the development of these basins. Therefore, it is appropriate to classify the depressions according to presumed dominant mode of their origin as follows: (1) deep-seated solution of salt or gypsum with accompanying surface subsidence or collapse; (2) solution of carbonate rocks at intermediate depths and subsequent collapse; (3) differential wind deposition and erosion, in some places accompanied by compaction of eolian silts; (4) differential silt infiltration; (5) animal action; and (6) faulting.

Acknowledgments.--Thanks are expressed to R. C. Moore, whose criticisms have improved the manuscript, and to Ada Swineford and A. R. Leonard for helpful advice.

Kansas Geological Survey, Geology

Placed on web September 2005; originally published March 15, 1951.

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

The URL for this page is http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/Bulletins/86_1/index.html