Prev Page--Structure || Next Page--Fields

Oil and Gas Sands

The oil and gas sands of Anderson County are characterized by their limited extent. They are not sheet sands which were deposited uniformly over a wide area, but they are long, narrow bodies or small restricted patches of sand buried in the shales. The long, narrow trends are called "shoestrings" because their length is so much greater than their width. Frequently, the stratigraphic horizon of any of these sands may be detected by the presence of sandy shale.

The chief productive sands have been named in accordance with the depth at which they are found. They are the 300-, 600-, 800-, and 900-foot sands. The application of the depths at which they occur as the names of the sands is inaccurate because their depth is varied by the dip, by changes in thickness of the formations, and by the topography. Other sands, which are oil-bearing in other parts of Kansas, but which have not yet furnished commercial production in this area, are below those that have received the most development to date.

The 300-foot sand

Shallow, stray sands at about this depth are irregularly distributed in the northeastern part of the county. Sands at different stratigraphic horizons, but approximately at this same depth, are inaccurately referred to as the same sand. The one encountered most commonly is a gas sand near the top of the La Cygne shale, which furnishes wells of about one-quarter million feet initial volume. Its maximum thickness is 35 feet, Generally the shallow gas has commercial value only when produced in conjunction with the gas from the deeper wells with greater volume.

Another sand, in the Nowata shale, has produced heavy oil in a few wells. These sands have very little commercial importance.

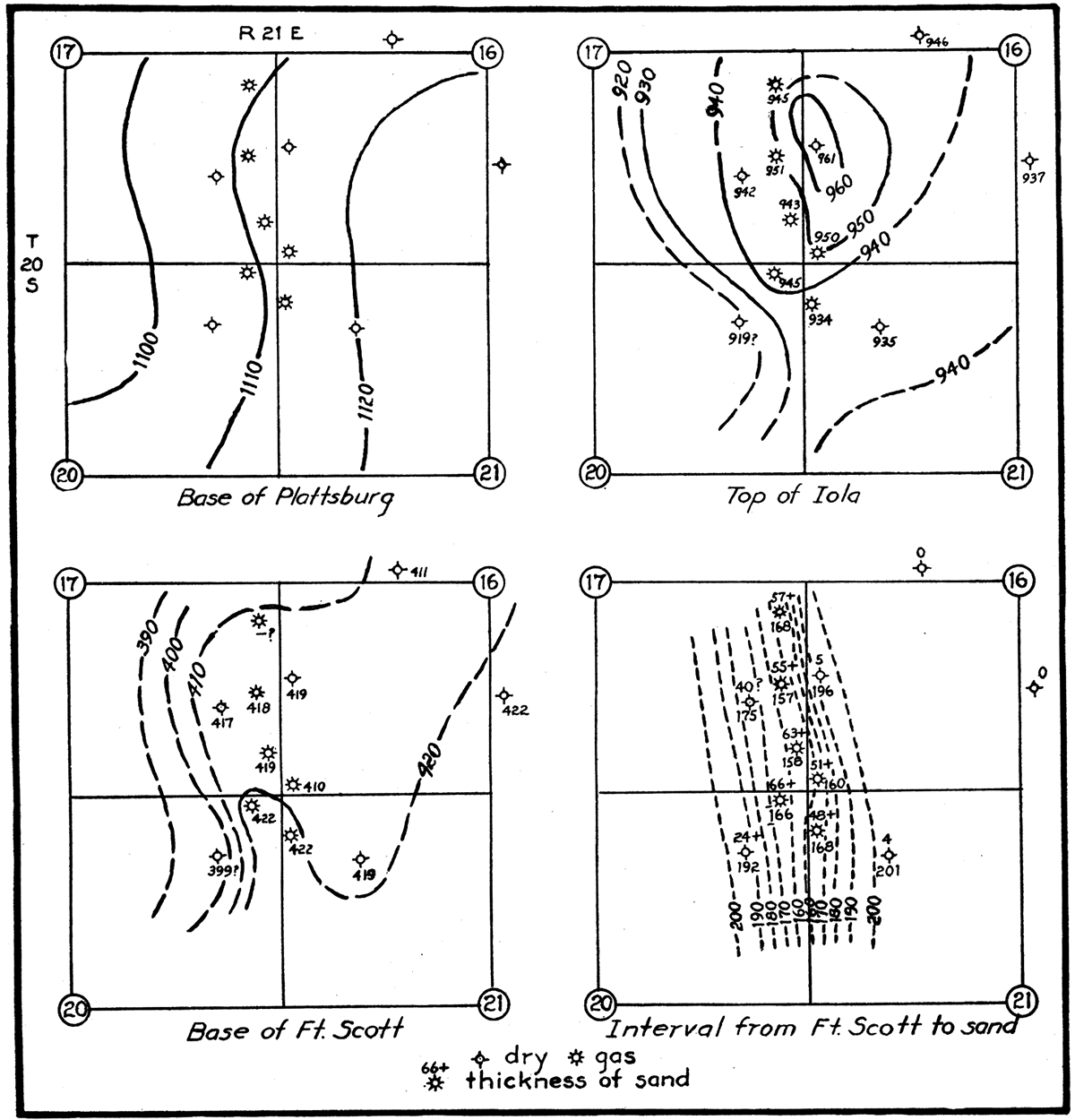

Figure 3—These plats indicate the unreliability of structural evidence in connection with small isolated sand deposits. Poorly recorded well logs, used in this instance without attempt for correction, account for some of the oddities of structure. The dip of the surface beds, as mapped on the base of the Plattsburg limestone, is practically normal. but the area shown is on the west flank of an anticline. If differential settling is the only cause of the flexure, the more pronounced dips should be in the Fort Scott limestone. The contours on the base of this member suggest that later westward tilting of the strata increased the "compaction-dip" above the down-dip flank of the sand body and decreased it above the up-dip flank. The plat at the lower right shows that the sand is a bar-shaped ridge with relief of at least 44 feet. The producers are confined to one row of wells along the crest.

The 600-foot sand

The 600-foot sand locally serves as a reservoir for gas. Deposits of this sand are chiefly straight, narrow bodies with convex tops. In many scattered wells throughout the county the sand contains only water. The maximum reported thickness is 60 feet. This sand was deposited at about the stratigraphic middle of the Bandera shale and is correlated with the Weiser sand of southern Kansas.

The 800-foot sand

The 800-foot sand, often referred to as the "shoestring" sand, produces most of the oil and some of the gas in Anderson County. It is very limited in extent and its thickness is equally variable. This sand occurs in two phases: (1) as long, narrow, sharply defined bodies with flat tops but convex bottoms, 800 to 1,400 feet wide, 0 to 60 feet thick, and several miles long, (2) as irregular patches covering 40 to 400 acres, and 0 to 30 feet thick. Both types of sand bodies are 20 to 50 feet below the top of the Cherokee shale and occupy approximately the same stratigraphic horizon as the Squirrel sand of Oklahoma.P The Squirrel sand is equivalent to the Prue (Aurin, 1917; also, Glenn C. Clark, personal communication). The sand is brown, fine-grained, and micaceous and is very impure locally because of included laminae of silty shale. Anderson County probably represents about the outward limit of sand deposition during the time this particular stratigraphic horizon was being laid down.

The 900-foot sand

The 900-foot sand furnishes practically all the gas of the county. Operators frequently call it the Colony sand because the first major development in it took place on town lots at Colony. The largest body of this sand has been traced through a gently-winding course for 16 miles in the central part of the county. This sand body, 75 to 100 feet below the top of the Cherokee shale, attains a maximum thickness of 140 feet and maximum width of about one-half mile. Lenses of shale are included, and it grades into sandy shale and broken sand both laterally and vertically. In the eastern part of the county are other straight, lenticular bodies of sand with a general north-south direction that are correlated with the Colony sand. They are 150 to 180 feet below the top of the Cherokee shale and are thinner, narrower and more sharply defined than the large Colony sand body. Most of them are 500 to 1,000 feet wide and 0 to 50 feet thick. They yield gas wells with 1 to 8 million feet initial open flow. All the sand at the 900-foot level is fine-grained, gray, and micaceous and varies over a wide range in purity, according to the amount of shale it contains.

Some people refer to the Colony sand as the Bartlesville, a name applied freely to sands in the Cherokee shale, even to scattered deposits a long distance from the type locality of the Bartlesville. Although the 900-foot sand of Anderson County was laid down at or near the true Bartlesville horizon, it has not been determined definitely as of that age.

Stray sand

On the southeastern edge of the Colony gas field a well which found only sandy shale at the 900-foot sand level was deepened to 1,000 feet, where a flow of about one-half million feet of gas was obtained from a stray sand. The daily production and pressure declined very slowly, probably because only one well was drawing gas from the reservoir. In scattered areas throughout the county this deep stray sand has been discovered, but with the exception of the Colony well, which is high structurally, all other holes have found only salt water. It is very likely that it will be productive elsewhere under the proper structural conditions.

Burgess sand

A remarkably thick sand lies on top of the Mississippian limestone in the extreme western part of the county. Several dry holes south of Northcott and between Northcott and Westphalia have penetrated 100 to 180 feet of it. A dry hole 3 1/2 miles west of Harris had 150 feet. These widespread occurrences indicate this sand may extend the entire length of the western side of the county. A few gas wells about 2 miles south of Northcott produce from the upper 10 to 15 feet of the deposit. Water is under the gas. Showings of oil have been reported in two or three dry holes. Perhaps gas or oil will be found in the upper part in places where the sand is relatively high due to uneven deposition or folding.

Top of the "Mississippi lime"

In that southeastern portion of the county set off by a line between Lone Elm and Selma the upper part of the "Mississippi lime" contains a cherty, rotten zone that is very porous. This zone may be the result of weathering before the advance of the Cherokee sea. Almost every well which has been drilled through this zone has found a showing of gas or low-gravity black oil. As yet not enough oil has been found in any well to make it a commercial producer. The amount of the showings is apparently more dependent on the porosity of the limestone than on structural conditions.

"First break"

Any change of formation which includes shale, sandstone, or sandy limestone between 5 and 75 feet below the top of the Mississippian limestone is referred to as the "first break." Where the break is sand or sandy lime, it invariably contains salt water. No production has been secured from it in the county, and so far as the writer knows, no showings have been credited to it.

"Siliceous lime"

The widespread "siliceous lime" of the Midcontinent region underlies Anderson County at a depth 300 to 350 feet below the top of the "Mississippi lime." This porous zone is the truncated, weathered top of the Arbuckle limestone of Ordovician age. It is the only one of the "second break" or "Wilcox" sand series common to Oklahoma that has been found in this area. One of the nine wells drilled to this deep horizon is reported to have had a showing of oil, but the others encountered great quantities of sulphur water.

Suggested Origin of the Sand Bodies

The sands of Anderson County represent individual units of deposition that can be outlined and studied separately. Where it has considerable thickness, the sand is concentrated into forms that resemble bars, shallow-water or beach deposits, or the fillings of channels. Cross sections of the oil sand can be secured with a fair degree of accuracy from the logs of wells 300 feet apart that are drilled through the sand into the underlying shale. Sections of the 900-foot gas sand cannot be outlined as definitely because the wells are located farther apart and, to avoid encountering water, drilling is stopped before the sand has been completely penetrated.

Bars

The deposits that resemble bars are long and narrow, straight or gently curved. The underside is practically flat or partly convex downward and the top is convex or nearly flat. The sand thins gradually to the edges. In places the total thickness is replaced by sandy shale before all traces of the deposit disappear into the surrounding shale. Fingers of sand 10 to 25 feet thick project 500 to 2,000 feet from one or both sides of some of the bodies. There appears to be no way to distinguish between the landward and seaward sides, probably because data are not available to outline the sand in detail. The unexpected shapes of some "bars" which have little resemblance to familiar types may be traceable to marine erosion, migration during deposition, and possibly to inaccurate descriptions and measurements in well records. However, it is likely that their shape is truly variable and that ideal forms are the exception.

The general processes by which bars are formed are so well known that the writer does not consider it necessary to describe them here (Johnson, 1915). Bar deposits are represented among all three of the main sand horizons of the county.

Shallow-water or beach deposits

The sand bodies which are believed to have been laid down in rather shallow water, perhaps on the floor of an embayment, are quite uniform in thickness. Their upper and lower sides are clean-cut, but they grade laterally into sandy shale. They are irregular in outline and the majority of them are oblong. In many places several small patches of sand at the same horizon are separated by barren zones of shale. The patches have no systematic arrangement among themselves, but taken as a whole form a distinct trend. The slight irregularities in the thickness may be due to deposition on an uneven sea floor or to work of currents or waves. Perhaps the sandless areas indicate the former presence of islands. If these sands were ever above the strand-line, as beach sands, the wind may have shifted them about. It seems likely that these sand bodies were laid down along the edge of a low land occupied partly by swamps. Coal is occasionally found near the same horizon. These deposits have largest representation in the 800-foot sand near the top of the Cherokee shales.

Channel fillings

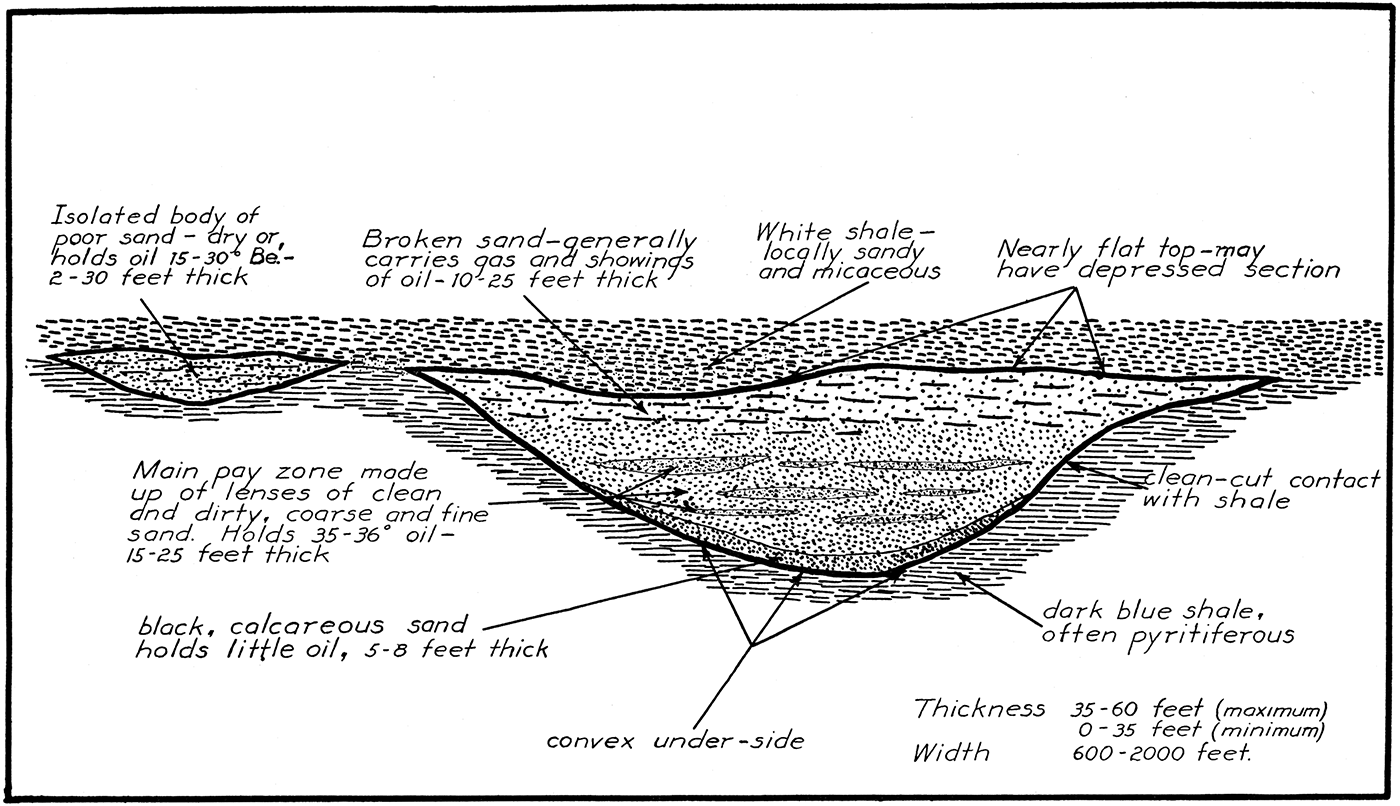

The channel-shaped deposits, which may be several miles in length but only a few hundred feet in width, are the most extraordinary of all the sand bodies. Such deposits in this district are gently curved but maintain the same general direction for 6 to 8 miles. The minimum amplitude of any of the curves is 2 miles. Their cross sections have considerable variation in shape but the cross-sectional area remains about the same. Where the channel is narrow, it is relatively deeper. The sections are not always symmetrical, but the deepest part swings from side to side. The top of the sand is nearly flat in most instances, but places exist where a shallow, channel-shaped depression has been carved in the sand, probably the final work of the current of the stream. In contrast to the depressions are convex portions projecting above the average level. They have the appearance of bars such as are commonly thrown up at the bends of streams. In some places sand or sandy shale is spread out in a thin layer 1/4 to 1/2 mile wide in the horizon of the top or slightly above the top of the main channel deposit. Developments to date have not shown that these isolated patches are always connected with the main body of sand. Dry holes that had no sand have been drilled between the thin deposits and the main sand body, but it is reasonable to expect that somewhere they are connected to the main body by narrow necks of sand that represent temporary cut-offs of the stream. The isolated deposits locally furnish small wells with oil of lower gravity than that in the near-by shoestring.

Figure 4—Typical cross section of a channel deposit to show its various features. The small body of sand at the side is a local feature. (Not drawn to scale.)

The channel filling varies in quality, but everywhere remains in: the class of fine-grained sand. The best is fine, sugary sand containing very little foreign material. Most of it has much silt and a large percentage of mica in the form of tiny flakes. Thin streaks of silty shale show that the material is cross-bedded.

The process by which the channels that were carved in the soft Cherokee shales were later filled to the top with sand seemingly cannot be explained by ordinary stream deposition. Present-day streams whose channels are nearly filled with sand flow in sharply meandering courses. The buried channels of' Anderson County are only gently curved. It is suggested that the history of the filling process which did not induce meandering is about as follows:

Sluggish streams that carried mostly mud emptied into a shallow embayment of the Cherokee sea whose low, marshy shore was several miles east of the Anderson County area. The sea bottom was a smooth marine floor that sloped very gently, providing shallow water several miles from shore. After uplift of the region, the sea began to retreat slowly, and as it retreated, the streams advanced their mouths and thus lengthened their courses on the lower end. Perhaps an increased gradient helped them cut rather straight channels, 40 to 50 feet deep, in the soft, freshly exposed sea bottom over which they made new paths to the sea. Their steep gradient and entrenched channels prevented their meandering. Sand, a product to be expected in a rejuvenated stream, was carried by these streams. Some of the sand came to rest on the channel bottoms; some was transported into the sea and was drifted along the shore by currents, finally to come to rest as beach sands and low bars. When subsidence of the land took place and the sea started to regain its former boundaries, it advanced first up the river channels. The sand which the rivers were carrying was dropped when it reached the quieter, deeper water and was added to that which already partly filled the channels. As the edge of the sea continued to advance, the sand-clogged part of the channels was pushed upstream. Probably a stage of tidal ebb and flow during the silting-up of the channels is responsible for the intricate lamination of mud with fine-grained sand. The surplus sand, beyond that needed to level up the filling, was spread out on the sea floor along the sides. This took place mostly at the western ends of the stream courses. Finally the entire area was submerged more deeply and a blanket of mud was deposited over the long strings of sand before any form of subaqueous erosion could disturb them.

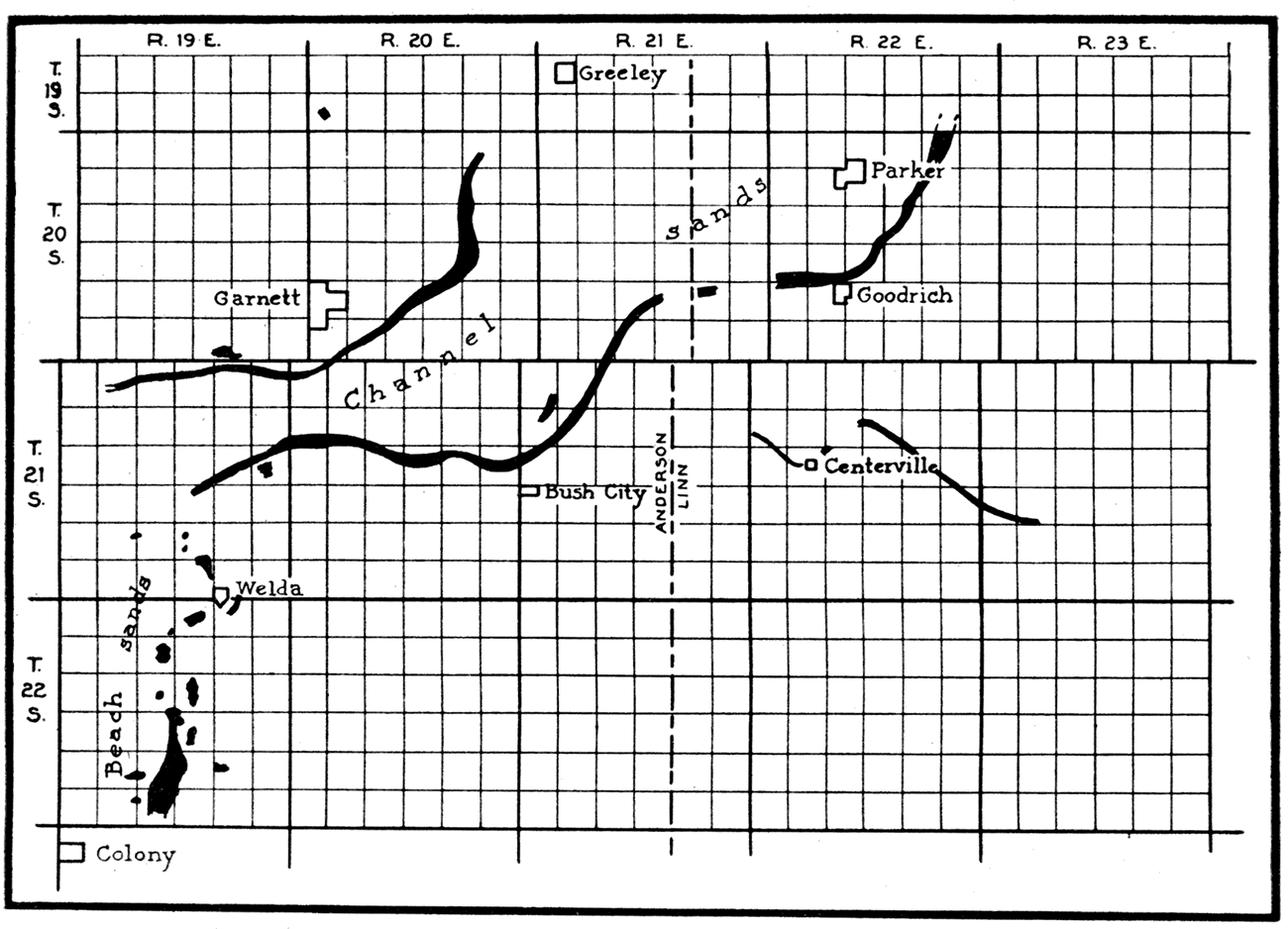

The theory thus outlined provides for an ordinary drainage system made up of trunk streams and their branches that were generally confined to single channels but locally may have sent part of their "raters down small natural depressions near the established courses to form temporary cut-offs. The comparatively straight channels already traced out do not suggest to the writer the existence of a braided-stream pattern. The ground plan of the "system" of channel deposits in Anderson and Linn counties (Fig. 5) indicates westward drainage. As yet none of these branches has been joined by drilling, but the outlook seems good for this to happen. In the older and more thoroughly developed Humboldt-Chanute district of Allen and Neosho counties, shoestring trends join each other like stream branches.

Figure 5—Deposits of the 800-foot, or "shoestring" sand, in the Anderson-Linn county district. The two types of sand bodies at the same horizon throw some light on the paleogeography of the time. It seems likely that other channels are in the area south of Bush City and Centerville. (Base map after Rich.)

The idea that these channel deposits are the fillings of delta distributaries does not appear acceptable, because the sand is confined to one horizon. The remains of a delta should contain much sandy shale and many fragments of channel fillings that were made by several distributaries continually changing their courses to the sea. A delta results from a building-up process and occupies !1 considerable stratigraphic interval composed of a large proportion of arenaceous material.

Prev Page--Structure || Next Page--Fields

Kansas Geological Survey, Geology

Placed on web Feb. 6, 2018; originally published June 15, 1927.

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

The URL for this page is http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/Bulletins/6_7/05_sands.html