Prev Page--Contents || Next Page--Camp Funston

Chapter I—The Western Theater of War

By Major Douglas W. Johnson

Note: This chapter is reprinted by permission of the author and publishers, Henry Holt & Co., from "Topography and Strategy in the War."

Geological Features

The violation of Belgian neutrality was predetermined by events which took place in western Europe several million years ago. Long ages before man appeared on the world stage Nature was fashioning the scenery which was not merely to serve as a setting for the European drama, but was, in fact, to guide the current of the play into blackest tragedy. Had the land of Belgium been raised a few hundred feet higher above the sea, or had the rock layers of northeastern France not been given their uniform downward slope toward the west, Germany would not have been tempted to commit one of the most revolting crimes of history and Belgium would not have been crucified by her barbarous enemy.

Influence of Terrain

For it was, in the last analysis, the geological features of western Europe which determined the general plan of campaign against France and the detailed movements of the invading armies. Military operations are controlled by a variety of factors, some of them economic, some strategic, others political in character. But many of these in turn have their ultimate basis in the physical features of the region involved, while the direct control of topography upon troop movements is profoundly important. Geological history had favored Belgium and northern France with valuable deposits of coal and iron which the ambitious Teuton coveted. At the same time it had so fashioned the topography of these two areas as to insure the invasion of France through Belgium by a power which placed "military necessity" above every consideration of morality and humanity. The surface configuration of western Europe is the key to events in this theater of war; and he who would understand the epoch-making happenings of the last few years cannot ignore the geography of the region in which those events transpired.

The Natural Defenses of Paris

The Paris Basin

What is now the country of northern France was in time long past a part of the sea. When the sea bottom deposits were upraised to form land, the horizontal layers were unequally elevated. Around the margins the uplift was greatest, thus giving to the region the form of a gigantic saucer or basin. Because Paris to-day occupies the center of this basin-like structure, it is known to geologists and geographers as "the Paris Basin."

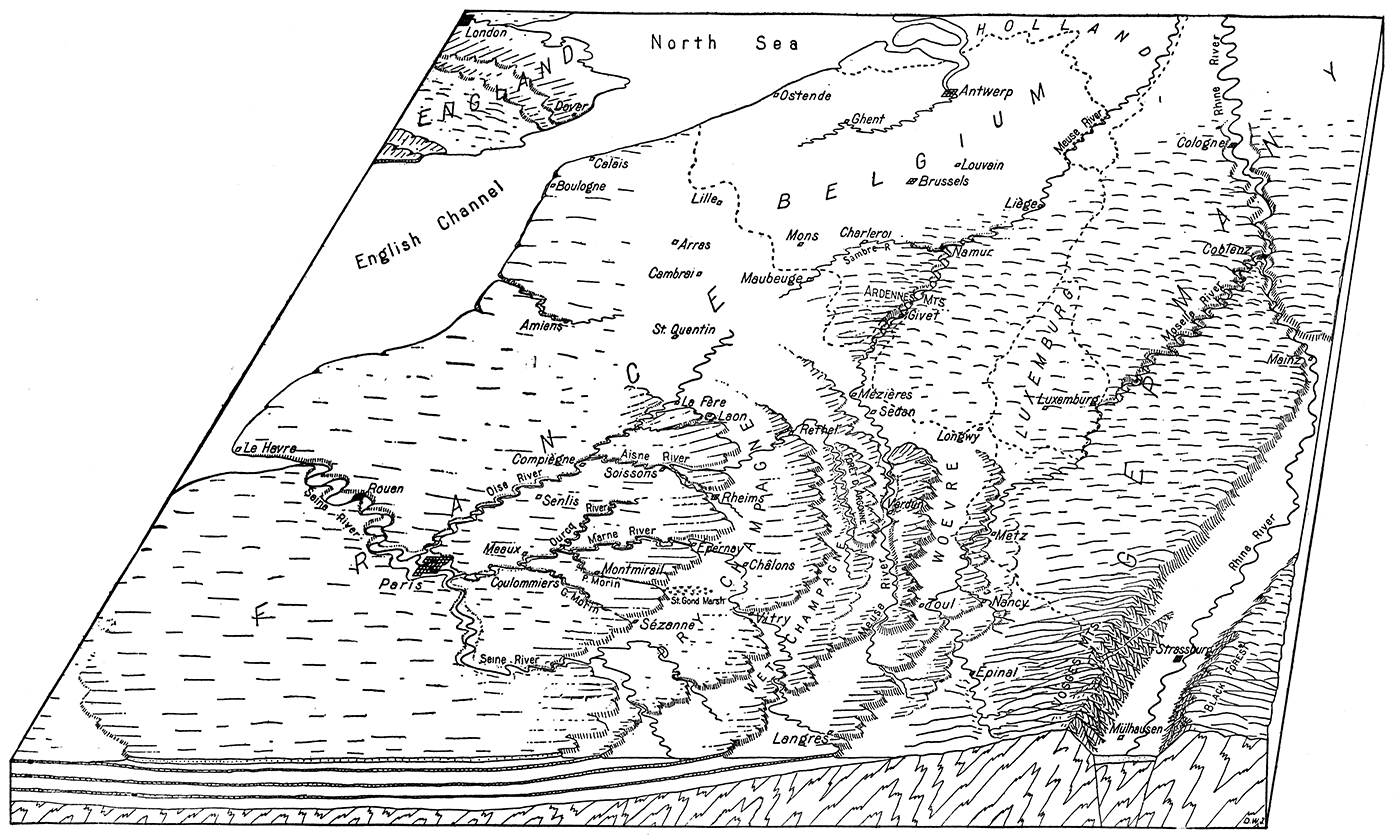

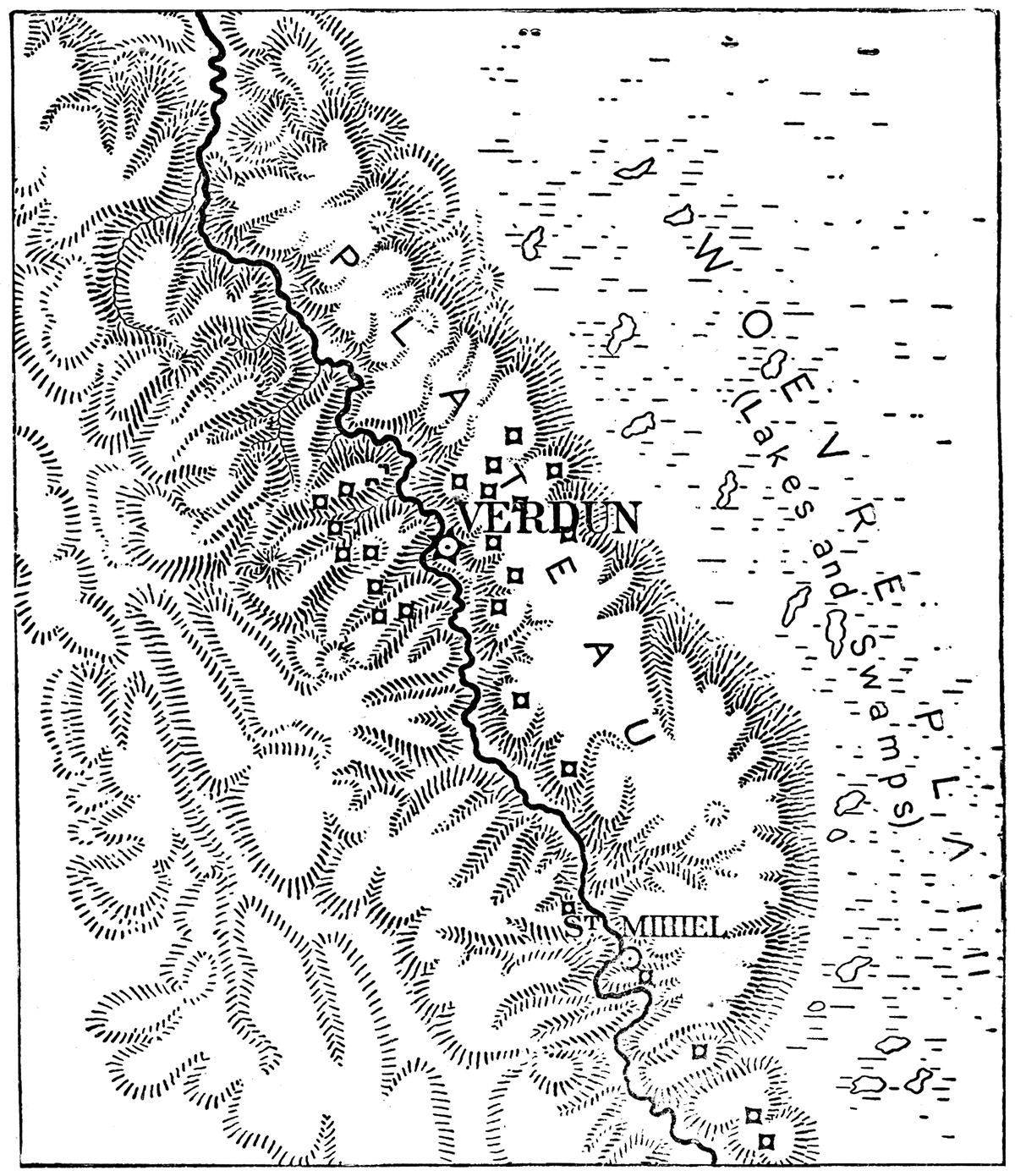

Since the basin was formed it has suffered extensive erosion from rain and rivers. In the central area where the rocks are flat, winding river trenches, like those of the Aisne, Marne, and Seine, are cut from three to five hundred feet below the flat upland surface. To the east and northeast the gently upturned margin of the basin exposes alternate layers of hard and soft rocks. As one would naturally expect, soft layers like shales have readily been eroded to form broad flat-floored lowlands, like the Woevre district east of Verdun. The harder limestone and chalk beds are not worn so low, and form parallel belts of plateaus, the "côtes" of the French. These plateau belts and the intervening parallel lowlands are best shown in bird's-eye view by a diagrammatic sketch of western Europe (Fig. 1). The diagram represents a block of the earth's crust, cut out so as to show in cross section the manner in which the hard rock layers have been eroded to form the plateau cliffs.

Figure 1—Diagrammatic view of the western theater of war, showing the principal plateaus and plains, mountains and lowlands, cliff scarps and river trenches which have influenced military operations. The underground rock structure is shown in the front edge of the block.

East-facing Scarps

The fact that the rock layers dip toward the center of the basin has one striking result of profound military importance. Every plateau belt is bordered on one side by a steep, irregular escarpment, representing the eroded edge of a hard rock layer; while the other side is a gentle slope having about the same inclination as the dip of the beds. As will be seen from the diagram, the steep face is uniformly toward Germany, the gentle back-slope toward Paris; and the crest of the steep scarp always overlooks one of the broad, flat lowlands to the eastward. The military consequences arising from this peculiar topography will readily appear. It is not difficult to understand why the plateau belts have long been called "the natural defenses of Paris."

Imagine yourself at Paris, and start on a tour of inspection eastward to the German border. First you traverse the central plateau of the Paris Basin, called the Isle of France, whose circular line of bordering cliffs were, according to an ancient theory, cut by the waves of the sea. Here and there, especially if you turn northward or southward in your journey, you will come suddenly upon the edge of a river valley trenching the plateau across which you are traveling. Descending the steep slopes of the valley wall, which are often clothed in forests, you reach the flat valley floor several hundred feet below, and make your way over the winding stream. Perhaps the season is wet, and you wade through marshes on both sides of the river until the dry land of the opposite valley wall is reached. Toiling painfully up the slope you at length come out again upon the flat upland of the plateau surface. Pausing to rest, you look back at the obstacle you have just traversed, and reflect that a number of such obstacles cross the plateau in parallel courses from east to west. You realize that they must prove serious barriers to the advance of armies moving southward or northward; and as you remember that two of these obstacles bear the names of the Marne and the Aisne, you have a fuller understanding of two notable chapters in recent military history.

As you journey onward you pass numerous quarries, some of them broad and deep. Cavern mouths tempt you to explore vast subterranean excavations where limestone or chalk in large quantities has been removed, leaving vast galleries and chambers which could easily house many thousands of troops safe below reach of the heaviest shell explosions. An army intrenched behind the natural moat of one of the east-west river trenches, as for example the Aisne, and utilizing surface quarries and underground caverns for the protection of its men, might well consider itself impregnable against every assault of the enemy.

The First Escarpment

Musing thus, you continue eastward, until suddenly you arrive at the brink of the first line of east-facing escarpments. Behind you stretches the plateau whose features you have just been studying. In front of you, to the east, spread out below like a gigantic map, is the level surface of the Champagne lowland. As you look down upon it you see roads, like narrow white ribbons, bordered on both sides by green vineyards, while the steep slopes of the escarpment itself are often cleared of their trees and cultivated. At your feet, where the west-flowing Marne cuts its gateway through the escarpment, lies the town of Epernay, while to the north the towers of Rheims cathedral mark the similar gateway of a branch of the Aisne. Southward the marsh of St. Gond occupies a former river valley on the flat floor of the plain, its boggy surface a trap which captured many pieces of German artillery. Far out over chalky flats to the east lies the famous armed camp at Châlone, Nothing is hidden from view in that broad panorama of plain.

View from the Crest

What a position is yours from which to check a westward advance upon Paris! Every enemy movement would be open to observation from the crest of the scarp, and could be broken up by fire from artillery concealed in ravines back from the plateau face. Assaults on intrenched positions on the slopes and crest of the scarp would be made with every advantage on the side of the defending troops. The level plain below offers little opportunity for the offensive to secure concealed artillery positions from which to make preparation for the uphill infantry charges. It was reported in early dispatches of the war that during the Battle of the Marne the German center, stretching eastward from Sézanne at the base of the cliffs farther south, was subjected to a disastrous artillery fire from the crest of the scarp which broke up concentrations of reserves on the plain and prevented the reinforcement of the German line at critical moments.

The Plain of Champagne

Profoundly impressed with the strength of this natural defense line before Paris, you descend to the plain of Champagne and move eastward over its surface. For thirty-five or forty miles your course is over a dry chalky soil, a region comparatively unfruitful, where only scattered growths of trees relieve the semi-desert aspect. This is known as the "Dry Champagne," as the rain which falls on the porous chalk soon sinks to depths which the plants cannot reach. Farther east is the "Wet Champagne," where a narrower belt of impervious clay keeps more of the water on the surface, there to form numerous brooks and marshes, and to support a goodly forest growth.

The Second Escarpment

Before reaching the Wet Champagne, you make a gradual eastward ascent which does not end until you stand, a second time, at the crest of an east-facing scarp. The lowland now spread out below you to the east is traversed in the north by the winding upper Aisne, slightly intrenched in the floor of the plain; and the main river gateways cutting through the escarpment are marked by the towns of Rethel and Vitry. Again you are impressed with the topographic advantages favoring the defenders of Paris from an attack from the east. The conditions are essentially those already noted from the crest of the first escarpment, save for the absence of the arid, chalky soil of the Dry Champagne.

The Third Escarpment

You push across the valley of the upper Aisne, on up the gentle back slope of the next plateau belt, until for a third time you stand at the crest of a steep east-facing escarpment, and look down upon a lowland spread out like a map at your feet. All about you the plateau is heavily forested, and cut here and there by the deep, wild gorges of numerous streams, which flow westward to the lowland just left behind, or eastward to the lowland at the base of the scarp. This wooded plateau belt is the Forêt d' Argonne, where more than one battle of France has been fought.

Verdun Escarpment

Descending the face of the Argonne scarp and crossing the valley of the Aire river, you continue eastward across a minor plateau strip and reach the winding trench of the Meuse. Past immortal Verdun and its outlying forts, you press on to the crest of the next great scarp. What a view here meets the eye! To the north and south stretches the long belt of plateau, cut into parallel ridges by east- and west-flowing streams—ridges like the Côte du Poivre, whose history is written in the blood of brave men. Below, to the east, lies the flat plain of the Woevre, whose impervious clay soil holds the water on the surface to form marshes and bogs without number. Here the hosts of Prussian militarism fairly tested the strength of the natural defenses of Paris, and suffered disastrous defeat. Moving westward under the hurricane of steel hurled upon them from above, their manoeuvering in the marshes of the plain easily visible to the observant enemy on the crest, the invading armies assaulted the escarpment again and again in fruitless endeavors to capture the plateau. Only at the south where the plateau belt is narrower and the scarp broken down by erosion did the Germans secure a precarious foothold, thereby forming the St. Mihiel salient; while at the north, entering by the oblique gateway cut by the Meuse river, they pushed south on either side of the valley only to meet an equally disastrous check at the hands of the French intrenched on the east-and-west cross ridges. Viewing the battlefields from your vantage point on the plateau crest, you read a new meaning in the Battle of Verdun. You comprehend the full significance of the well-known fact that it was not the artificial fortifications which saved the city. It was the defenses erected by Nature against an enemy from the east, skillfully utilized by the heroic armies of France in making good their battle cry, "They shall not pass." The fortified cities of Verdun and Toul merely defend the two main gateways through this most important escarpment, the river gateway at Verdun being carved by the oblique course of the Meuse, while the famous "Gap of Toul" was cut by a former tributary of the upper Meuse, long ago deflected to join the Moselle. Other fortifications along the crest of the scarp add their measure of strength to the natural barrier.

The Metz Escarpment

Once more you resume your eastward progress, traverse the marshy and blood-soaked plain of the Woevre, ascend the gentle back slope of still another plateau belt, and stand at last on the crest of the fifth escarpment. Topographically this is the outermost line of the natural defenses of Paris, and as such might be claimed on geological grounds as the property of France. [Note: A discontinuous, low scarp farther east is not here considered.] But since the war of 1870 the northern part of this barrier has been in the hands of Germany, who purposed in 1914 to widen the breach already made in her neighbor's lines of defense. Metz guards a gateway cut obliquely into the scarp, and connects with the Woevre through the Rupt de Mad and other valleys.

Nancy Gateway

Farther south is Nancy, marking the entrance to a double gateway through the same scarp. Here in the first week of September, 1914, under the eyes of the Kaiser, the German armies, moving southward from Metz, where they were already in possession of the natural barrier, attempted to capture the Nancy gateways and the plateau crest to the north and south. Once again the natural strength of the position was better than the Kaiser's best. From the Grand Couronné, as the wooded crest of the escarpment is called, the missiles of death rained down upon the exposed positions of the assaulting legions. The Nancy gateway was saved, and more than three years from that date is still secure in the hands of the French. The test of bitter experience has fully demonstrated to the invading Germans that it was no idle fancy which named the east-facing scarps of northern France "the natural defenses of Paris."

River Gateways

It is but reasonable to expect that many of the rivers of northern France should flow down the dip of the rock layers and converge toward the center of the Paris Basin, where the beautiful city itself is located. A glance at a map, or at the diagram opposite page 4, will show that this expectation is fully realized. Most of the river gateways through the concentric lines of escarpments have been carved by these converging streams, or by streams which did so converge before they were deflected to other courses by drainage rearrangements resulting from the excavation of the parallel belts of broad lowlands. Of course these natural openings through the plateau barriers have great strategic value, and must figure prominently in any military operations in the Paris Basin. Some of them constitute the only feasible routes along which armies and their impedimenta may cross the barriers, as elsewhere steep grades and poor roads are the rule. At each of them a town of greater or less importance has sprung up, and both town and gateway are protected either by permanent forts or hastily constructed field fortifications. So great is the strategic value of the principal gateways, such as those near Toul and Verdun, that we find them marked by some of the most strongly fortified cities in the world. The fortifications dominate the roads, canals, and railway lines which pass through the openings, and must be reduced before the cities can be occupied and the transportation lines freely used. This explains the significance of the frequent mention, especially in the war dispatches of the first year, of such towns as La Fère, Laon, Rheims, Epernay, and Sézanne guarding gateways in the first line of cliffs east of Paris; of Rethel and Vitry in the second line; of Bar-le-Duc at the south end of the third; of Verdun and Toul in the fourth; of Metz and Nancy in the fifth; to say nothing of other points in the same and lesser scarps not considered in this volume.

The importance of the strategic gateways will readily appear if we consider their relation to principal railway routes. No railway of eastern France can traverse the country from the German frontier to Paris without seeking out several of these fortified gateways in succession. Take, for example, the main through line from Strassburg to Paris. After crossing the German border it follows the valley of the Meurthe a short distance to reach one of the two Nancy gateways. Turning west through this opening in the Metz-Nancy escarpment, it makes straight for the famous Gap of Toul in the Verdun-Toul escarpment. Once through the Gap, the line bends north to find an opening in the low continuation of the Forêt d'Argonne scarp near the town of Bar-le-Duc. Westward from here the route crosses the Wet Champagne to Vitry, where there is a gateway through the Rethel-Vitry escarpment. At Vitry the line divides, one branch turning northwest to cut through the innermost line of cliffs at the Epernay gateway, the other continuing west to make use of the notch at Sézanne. Evidently there are along this one line at least five strategically important defiles through a corresponding number of military obstacles, all of which defiles must be controlled by the armies which would make free use of the Strassburg-Paris route.

The Sedan Lowland

Toward the northwest the several lines of plateau escarpments gradually descend, and ultimately merge with the undulating plain of northern France. The low land between these fading escarpments on the one hand and the rough country of the Ardennes mountains on the other, gives a roundabout but easy pathway along which one might reach Paris by swinging west beyond the ends of the scarps. Longwy, Montmédy, Sedan, and Mézières are the important points along this route, which is followed by a railway of much strategic value and which was quickly seized by the Germans after they had reduced the antiquated fortifications affording it a poor protection. As a route for an advance on Paris it is too circuitous to be of prime importance.

The Vosges Mountains and Rhine Valley

Beyond the limits of the natural fortifications of Paris are three outlying regions, each possessing a peculiar topography which has indelibly stamped its impress on the western campaigns. These regions are: to the east, the Vosges mountains and the valley of the Rhine; to the northeast, the mountains of western Germany and southern Belgium; to the north, the plain of northern France and Belgium. Let us examine these regions in the order named.The Rhine "Graben."

It will be seen from the diagram, Figure 1, that the folded rocks underlying the horizontal layers of the Paris Basin come to the surface at the east, forming rugged mountains from which the later beds have been completely eroded. Originally this eastern rim of the Basin was a broad north-south arch, with a gently rounded summit; but a north-south block of rock extending along the crest, and bounded by two parallel fractures or rifts in the earth's crust, dropped down several thousand feet, giving the broad, flat-floored valley. of the middle Rhine, or the Rhine Graben as it is known to the Germans. The river has spread a thick mantle of sand and silt over the surface of the down-dropped block, and now swings in a gracefully curving channel in its own deposits. The fertile plains of this valley floor constitute that part of the province of Alsace which the French are most anxious to recover from the Germans.

The Vosges Barrier

The two remaining limbs of the former arch, facing inward toward the down-dropped central strip, are known as the Vosges mountains on the west and the Black Forest on the east. Each of these ranges has a gentle slope away from the valley, and a steep face toward the valley representing the once nearly vertical fracture surface now eroded into sharp crested ridges and narrow ravines. Both slopes of each range are sufficiently rugged to make agriculture difficult and the building of roads and railroads expensive; hence the ranges are but little developed, and much forested land remains. But it is on the steeper slopes which lead abruptly downward to the flat floor of the Rhine valley that the ridges are most rugged and the forest most unbroken. Here the movement of large bodies of troops is particularly difficult, especially if the must ascend the slopes in the face of a determined enemy.

Invasion of Alsace

It was not political expediency alone which led the French to invade southern Alsace at the beginning of the war. The international boundary line follows the crest of the southern Vosges, and it was much easier for the French to move up the gentle west slope of the Vosges, capture the passes, and then sweep down the steep eastern face upon the flat plains about Mülhausen, than it was for them to cross the boundary farther northwest, where no such advantage was furnished by the topography. A French soldier, writing home from the battle line in the Vosges, described the influence of topography upon the fighting in that district in the following words: "Our task has been much easier in the southern Vosges than farther north. In the south it is all downhill after we cross the border; but in the north we must fight uphill against the Germans after we have entered their territory, as there the boundary line lies west of the mountain crest."Figure 2—Güntherstal, a typical valley of the Vosges mountains.

It has been stated in press reports that a commander of German forces at Mülhausen, ordered to lead his men across the Vosges mountains into France, made three futile attempts to carry the heights of the range in the face of French artillery. Then came an urgent message from the Kaiser: "The crest of the Vosges must be carried at any cost." A fourth desperate assault by the intrepid commander ended in his defeat. Retiring to his quarters the unhappy general, according to the story, committed suicide, first sending to his Kaiser this message: "The Vosges cannot be crossed. Come and try it yourself." I would not care to vouch for the truth of the story, but it serves to illustrate the peculiar surface features of the Vosges which render their ascent comparatively easy from the French side of the border but very difficult from the German side. This is the key to the significant fact that after three years of desperate offensives the only place where the German troops have been unable to expel the French from German soil is on the steep eastern face of the Vosges mountains.

In this connection it is interesting to note that should the French succeed in pushing the Germans back to the east side of the Rhine, their further eastward advance in southern Germany would then be opposed by precisely the same topographic difficulties which have long retarded the westward movement of the Germans in southern Alsace. The Black Forest will replace the Vosges in immediate importance, and while the Germans hold the crest and more gentle eastward slope of this range the French will find assaults against the steep west-facing scarp both costly and difficult.

The Belfort Gateway

Not far south of Mülhausen, but beyond the limits of the drawing, Figure 1, the Vosges mountains descend to a low pass which connects the Rhine valley with the valley of the Saône in eastern France. In this pass, guarding the strategic gateway from one valley to the other, stands the mighty fortress of Belfort, the southernmost of the great fortifications erected against a German invasion. Entrance to France by this route is easy, so far as the natural physical features alone are concerned; and in the commercial intercourse between the two nations the gateway has played an important role. But the opening is narrow enough to be effectively defended by the fortress in its center and to permit the concentration of troops in such numbers as to render its passage by an invader extremely difficult. Whether the fortress which withstood the attacks of the Germans in 1870 can defy the guns which reduced Liége, Namur, Maubeuge, and Antwerp will be determined only in case the Germans can push the French field army back far enough to bring their heavy siege artillery within range of the walls of Belfort.

The Mountains of Western Germany and Southern Belgium

The Mountainous Upland

North and west of the Vosges mountains the older series of folded rocks, exposed at the surface around the margin of the Paris Basin, have not been raised so high as in the Vosges. Instead they form an upland of moderate elevation, which was once a nearly level erosion plane; but which, since the uplift, has been cut into hills and valleys by many branching streams. This hilly country is known as the Slate mountains, the Haardt, the Eifel, and by other names in Germany, and as the Ardennes in southern Belgium. Although usually described as mountainous, the most striking feature of the area is the remarkably even sky-line which appears in every distant landscape view, and which is proof that the much folded rocks were once worn down to a surface of faint relief, after which warping raised the surface to its present position and permitted its dissection by river erosion. The upland is now so badly cut up by streams that cross-country travel is difficult, and transportation lines tend to follow the valleys.

Valley Defiles

Two main rivers cut deep trenches across this upland from southwest to northeast—the Moselle and the Meuse; while the lower Rhine transects it from southeast to northwest. Despite its excessively meandering course the Moselle gorge has been, from time immemorial, one of the chief pathways through the broad mountain barrier, and the strongly fortified city at its junction with the Rhine bears a name, Coblenz, which reminds us of the fact that in Roman times this was recognized as an important "confluence." In the present war the Moselle has served as the chief line of communication for one of the German armies of invasion, but if the Allies succeed in driving the invaders out of Belgium and back toward the Rhine, the great natural moat of the Moselle trench would change its role, and become a military barrier of the first importance, behind which the Germans might hope to check the Allied advance.

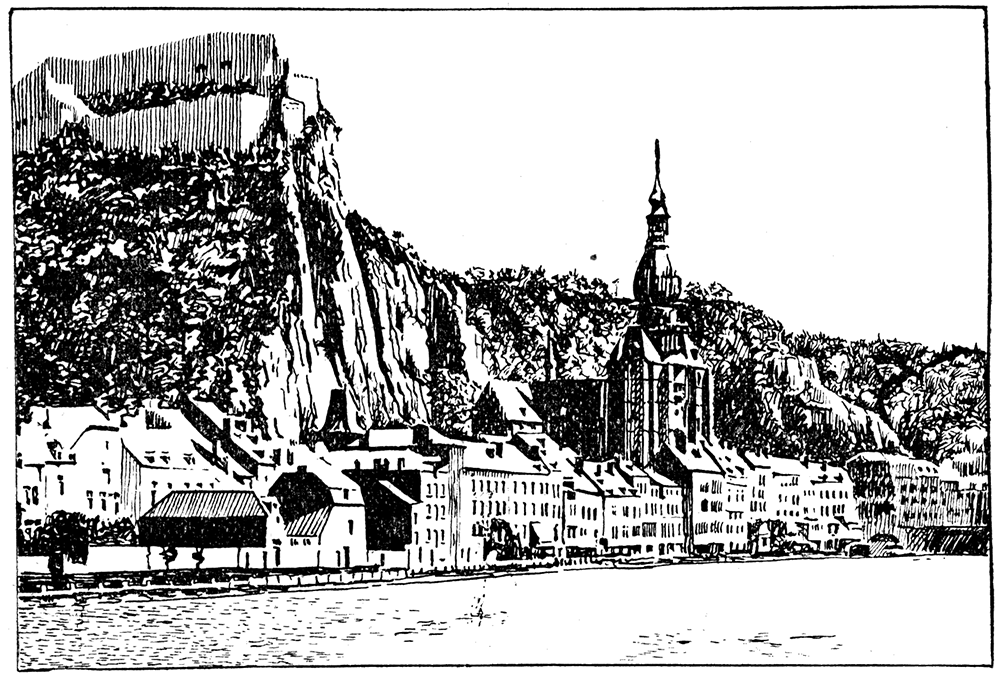

Figure 3—The gorge of the Meuse river at Dinant, showing steep, rocky sides of the gorge and the old fortress of Dinant. The Meuse river is a natural barrier of greatest importance in military operations.

The gorge of the Meuse is the second great natural highway through the upland barrier, and cleaves its way through the heart of the Ardennes mountains. Less winding than the Moselle, it is scarcely less important, especially if we include the branch gorge of the, Sambre, which joins the main trench at Namur. For the Sambre leads one southwestward to a low divide whence the headwaters of the Oise may be entered and followed directly to Paris. The combined Meuse-Sambre-Oise valley route is followed by a through railway line from Berlin to Paris, and for this reason was heavily guarded by the fortifications of Liége, Huy, Namur, and Maubeuge. Commanding the main gorge of the Meuse southward from Namur were-the forts at Dinant and Givet,

Both the Meuse and the Sambre trenches, now serving as principal lines of communication and supply for the German armies, were utilized by the Allied armies in August, 1914, as protective barriers behind which they waited to receive the first great shock of the German onslaught. The main Allied front faced north, and between Namur and Charleroi was protected by the lesser gorge of the Sambre; while the right flank enjoyed the admirable protection of the deep, steep-sided canyon of the Meuse. Those familiar With the steep, rocky walls of this larger trench will readily appreciate what a high defensive value it must have possessed. The causes of its ultimate abandonment by the Allied forces are touched upon in another chapter.

Gorge of the Rhine

The famous gorge of the Rhine, with its precipitous walls from which ruined castles look down upon the swift current of the great river, is better known to the world than the valleys of the Moselle and Meuse. From the earliest times it has been one of the chief routes of transportation and communication in western Europe, and today five important transport lines thread the narrow defile—two railways, one on either side of the river; two auto roads, one on either side; and the steamboat route on the river itself. In few places in the world can one find such a striking contrast as when, standing on the upper rim of the gorge, he looks out over the quiet farms and sleepy villages on the upland surface, then down upon the busy thoroughfare where trains, autos, wagons, and steamboats form a constant stream of hurrying traffic.

The two ends of the Rhine trench are guarded by Mainz and Cologne, two of the strongest fortified cities in Germany; while near the middle stands the strong fortress of Coblenz. Here then is a natural moat of impressive dimensions, carrying a swift, deep river, and heavily fortified at its most accessible points. German armies retreating from Belgium in the north could hope to check, along this trench, the most vigorous assaults of a pursuing enemy. Thus far, however, we are concerned With the Rhine trench as a line of communication connecting central Germany with military bases in the west from which attacks on France could most conveniently be launched. It is evident that two armies with headquarters at Coblenz and Cologne, and supplied by the railways, auto roads, and steamer routes which pass through the Rhine gorge, could attack France simultaneously if one ascended the Moselle to Luxemburg and the other passed from Cologne westward around the north side of the hilly country to the Meuse, and then followed southward up that valley. Hence it was that in the early weeks of the war we heard much of the "army of the Moselle" and the "army of the Meuse"; and the capture of Liége, Huy, Namur, Dinant, and Givet marked the progress of the latter army along the best pathway through the Ardennes.

The Plain of Northern France and Belgium

The Undulating Plain

Northward from Paris, and west of the fading belts of plateaus and scarps which characterize the eastern and northeastern sectors of the Paris Basin, stretches the undulating plain of Normandy, Picardie, and Artois. The underlying rock layers are practically horizontal and are exposed in picturesque manner along the coast where the waves of the sea have cliffed the margins of the land. Branching streams of moderate size have dissected the surface of the plain into a complex system of low hills with gently rounded slopes, those sufficiently large to be called rivers having eroded shallow valleys whose flat floors are not infrequently, as in the case of the Somme, covered with ponds and marshes. Above the valley bottoms the uplands are dry, and crossed by a network of excellent roads and railways. Even where valleys interrupt the surface the slopes are gentle, and in all this region there is not a single military barrier of the first magnitude. Marshy valleys of small streams, hill slopes, and occasional low ridges would figure in intensive fighting where opposing armies were deadlocked; but striking topographic barriers do not exist.

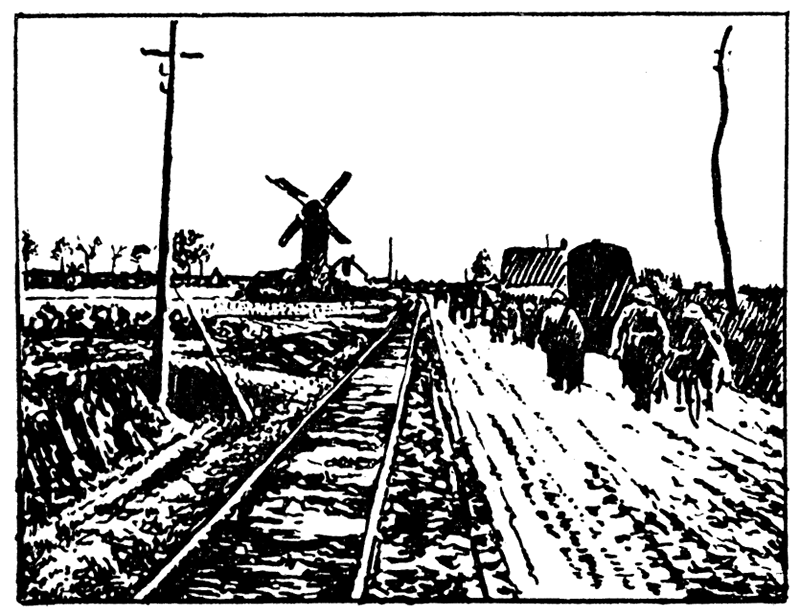

In Belgium the plain continues, but takes on a double aspect. From the margin of the hilly Ardennes northwestward toward the sea the surface is much like that described above, except that it is in general more gently undulating, even monotonously level over broad areas. Roads and railways make a dense network affording excellent communications in every direction. Nearer the coast, however, the land slopes down beneath the level of high tide, and becomes an absolutely flat, treeless plain. Belts of sand dunes along the shore and artificial dikes alone prevent the waters of the sea from flooding the land when the tide is high. Rivers crossing this belt must themselves be diked to prevent the indefinite spreading of their waters. Thus it happens that they are practically converted into canals, and like the lower Yser are called indifferently "canals" or "rivers." A close-set network of smaller canals helps to drain the flat, marshy surface, but forms an endless system of obstacles to free movement through the region. The level of permanent ground water is at or near the surface, and trenches dug in the marshy soil can scarcely be effectively drained. Trench life here is at its worst, and omnipresent mud adds its miseries to field life on the Flanders plain.

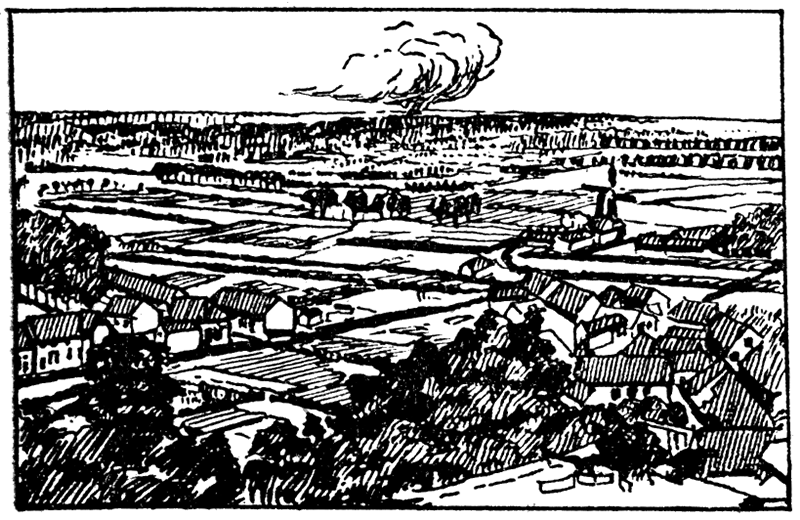

Figure 4—A typical scene on the flat plain of Flanders.

The higher parts of the plain, both in France and in Belgium, are covered with deposits of fine-grained loess and loam which afford a fertile soil easily cultivated. As a result the population is dense, and agriculture flourishes. Forests have been largely removed to permit the intensive farming of every available acre. It will be evident, therefore, that both the richness of the country and its favorable topography combine to make this plain a natural pathway from eastern and central Europe into France. It has, indeed, been called the gateway to northern France, and forms part of the greater plain belt over which one may travel by rail from northeastern Russia to the Pyrenees without passing through a single tunnel and without rising 600 feet above the level of the sea. From the military standpoint it presents four prime advantages: it is interrupted by no topographic barrier of serious importance; it is supplied with numerous parallel roads and railways by means of which to advance simultaneously different columns of troops; it is productive enough to supply food for the sustenance of large armies for long periods of time; and it passes close to important coal and iron deposits in the borders of the Ardennes, and has, indeed, important coal fields lying immediately below its level surface.

The Liége Gateway

In concluding our examination of the plain, let us note one peculiar feature of its position in eastern Belgium. Here the rugged country of the Ardennes reaches north to the vicinity of Liége, while Holland sends far southward a great peninsula of her territory in the form of the province of Limburg. The Belgium portion of the plain is thus narrowed to a neck of land only a few miles in width. German troops, desiring to enter the Belgium plain would thus find themselves confined between the hill country on the south and Dutch territory on the north. Across the narrow gateway cuts the valley of the Meuse river, and blocking passage of both river and gateway stood the forts of Liége. Manifestly free access to the broader plain beyond would not be possible until the forts had been reduced and their guns silenced.

Figure 5—The level plain of Belgium across which the main German advance on Paris was launched. Note the intensive cultivation of the plain. In the distance is the smoke of a burning town, set on fire by artillery.

Summary

We have completed our survey of the surface features of the western theater of war, and have found that the Vosges mountains, the mountains of western Germany and the Ardennes in Belgium, constitute a broad outer zone of comparatively difficult country, within which concentric belts of plateaus with east-facing scarps defend the most direct approaches to Paris. Only through Belgium into northern France is there a level pathway, free from obstacles, of great breadth most of the way, and provided with every facility for the rapid movement and prolonged sustenance of large armies. In the following pages we will see how profoundly these physical features affected the general plan of the German campaign and the detailed movements of the opposing armies.

The Plan of Campaign

First Route of Invasion

If the reader will turn back to the diagram, Figure 1, he will see at a glance that four principal routes of invasion were open to Germany in her campaign against France. She could, for example, concentrate her main armies in the valley of the Rhine with bases at Strassburg and Mülhausen, and in the country about Metz to enter by the so-called Lorraine gateway. An advance westward from between Strassburg and Mülhausen would encounter the steep east-facing scarp of the Vosges mountains, a topographic feature which, as we have already seen, imposes practically impossible conditions upon a German offensive. On the other hand, the main advance from this region might; be made by turning either end of the mountain barrier, passing through the Belfort gateway between the Jura mountains and the southern end of the Vosges; or between, the north end of the range and Luxemburg, through the gateway of Lorraine. In the first instance the ring fortifications of Belfort block the way, and since they effectively command every transportation line through the pass, their complete reduction would be necessary before an advance would be possible. From the southern foothills of the Vosges to the neutral territory of Switzerland in the Jura foothills the distance is but ten or fifteen miles, and the narrowness of the gap would favor the defense and prevent satisfactory manoeuvering of the attacking forces. Firmly intrenched in the gateway, their left flank secure against the difficult Vosges and their right flank protected by the neutral Swiss hills, supported by one of the four strongest fortified camps of France and supplied by adequate rail connections with the rear, the French armies could render an advance into their country by this route at best a slow and costly undertaking.

In order to understand the German plan of campaign we must remember that rapidity of action was of its very essence. German strategists have long maintained, and German statesmen at the outbreak of the, war frankly asserted, that to win the war the German armies must drive swiftly to the heart of France and bring that country to her knees before Russia should have time to mobilize and become a pressing danger on the east. In the German plan no route of invasion was practicable which would impose on the advance any appreciable delay. German and Austrian heavy artillery might account for the permanent fortifications of Belfort within reasonable time once they were fairly under fire; but the topography favored a long and obstinate defense from field works, which would perhaps prevent the big guns from coming within effective range of their objectives. The Belfort gateway might become the scene of important subsidiary operations, but German necessities required a topographically more favorable route for the main invasion.

The Lorraine Gateway

The Lorraine gateway is broad and, since the war of, 1870, largely in German territory. Metz is an admirable fortified base and is connected with Strassburg by excellent rail communications, It was by this route that the Prussian armies passed in the former war, whereas at the gate of Belfort they knocked in vain. West of Metz the German border is closer to Paris than any other point. Here, then, would seem to be an appropriate point from which to launch the main attack upon the French capital.

But to reach this conclusion is to forget the surface configuration of the Paris' Basin. Just over the French border is the broad, marshy plain of the Woevre. Dominating it on the west is the steep escarpment crowned' at short intervals by permanent fortifications from Verdun to Toul, and offering exceptionally advantageous positions for temporary .field works commanding the plain below. At the two points mentioned the only practicable gateways through the barrier are heavily fortified. Beyond, to the west, the same unfavorable topography is repeated again and again; always a steep scarp toward Germany, commanding a plain over which the invading troops must advance; always a gentle back slope down which the defending armies might retreat to the next scarp if too heavily pressed, while rear guards on the formerly occupied crest held the invaders temporarily at bay. If victorious along one plateau scarp, the invading armies would be checked at the next and compelled to fight the battle anew. Delays at the fortified gateways must be expected even if the forts were invested and the main armies pressed on to the barrier next west. Narrow and few in number; the gateways afford insufficient lines of communication for vast armies advancing and fighting, while the construction of new roads suitable for heavy traffic up the escarpments and over the plateaus would be an engineering feat involving an enormous expense in labor and time.

Clearly the route from the middle Rhine country westward into France must be eliminated as the main path of invasion in a campaign demanding rapidity of action as its chief object. The failure of the Crown Prince's army to break through the gateway at Verdun, the failure to capture the plateau crest west of the Woevre, and the failure to secure the Nancy gateways and reach the Gap of Toul are sufficient vindication, from the military standpoint, of the German staff's determination to avoid the difficult terrain of northeastern France and the delays it would inevitably impose on military operations, The belt, of fortifications alone would probably have weighed but little in the Teuton plans. Their confidence in their heavy artillery was supreme, and was fully justified by the speedy fall of every fort coming effectively under its fire. But the defenses of Nature can not be blasted away by the devices of man, and it was these defenses and not the permanent forts which saved Nancy, Toul, and Verdun.

Second Route of Invasion

A second route of invasion is from the northeast, following the course of the Moselle trench to Luxemburg and thence into France by way of Longwy or Metz. Such an advance could base on Coblenz and Trier, and would in the one instance involve the violation of neutral Luxemburg, and in the other bring the armies to the same advanced base (Metz) used by the troops moving west from the middle Rhine. In either case the further progress of the armies would encounter the same difficult terrain of the Paris Basin which rendered impracticable the first route, as described above. Large armies must undoubtedly push through the Lorraine gateway, capture the important iron deposits within easy reach of Metz, and forestall any attempt of the French to invade Germany by this route. But the main striking arm of the German military machine must operate along some other path.

Third Route of Invasion

To a lesser degree the route from Cologne, around the north side of the Ardennes, past Aix-la-Chapelle, and so to the trench of the Meuse through the mountains, is open to the same objections. Once the invaders were in French territory the plateau scarps could be crossed near their western extremities, where they constitute less formidable obstacles. Nevertheless the terrain is far from favoring a speedy advance on Paris. The scarps are sufficiently pronounced to give commanding artillery positions and to restrict free movement to a limited number of gateways. The innermost line of cliffs is especially forbidding, and its gateways are guarded by the fortifications of La Fère, Laon, Rheims, and Soissons. Moreover, to conduct the main offensive, with its principal line of communications a single railway running back through a narrow mountain gorge in hostile territory would be inadvisable if more favorable conditions could be found a short distance to the west. The "army of the Meuse" was, therefore, destined to play a subsidiary role in the invasion.

Fourth Route of Invasion

There remains the fourth route, by way of the Belgian plain. Entering, as before, by the Liége gateway, invading armies could spread westward around the northern side of the Ardennes, through Louvain and Brussels, swinging gradually southwest past Mons and Charleroi, Cambrai and Le Cateau, on past St. Quentin, and so down to Paris. The left flank could profit by the Sambre-Oise valley route, while the right flank could swing as far out over the plain as circumstances required. The pathway here is broad and level and no topographic obstacle bars the way. It is a route which enables an invader to take in the flank the entire series of plateau barriers farther east. Roads and railways are excellent and numerous, permitting the rapid simultaneous advance of different columns of troops. The country is fertile and highly productive, providing sustenance for large armies. With the occupation of this route would go the conquest of deposits of coal and iron of immense importance to the invaders. Back of the armies operating in France would be a broad network of first-class lines of communication and supply. Assuredly of the four possible routes of invasion this is the one incomparably the best so far as its physical characteristics are concerned.

There existed, however, some serious objections to an advance on Paris by way of the Belgian plain. The distance from the nearest point on the Franco-German boundary, near Metz, to Paris is about 170 miles as the aeroplane flies. From the German-Belgian border to Paris, via the Belgian plain, the distance is approximately 250 miles. The latter route is, therefore, nearly fifty percent longer than the legitimate route directly from German territory into France. Not only this. The longer route involved the violation of Belgian neutrality, and if Belgium and England were faithful to their treaty obligations and true to their national honor, must inevitably bring the Belgian army and the British army and navy into the field against the invader. Yet this was precisely the route over which the great mass of the German armies were hurled. The smooth Belgian plain was to serve as the slot along which the German bolt should reach the heart of France.

Military Necessity

Surely the choice of an invasion through Belgium must have been dictated by some very compelling reason to justify it in the minds of the German general staff. That reason is to be found in the topographic features of western Europe, which rendered a swift advance on Paris impossible from the east, but comparatively simple from the north over the broad pathway of the Belgian plain. "He who is menaced as we are can only consider the one and best way to strike," said the, German chancellor. "Belgian neutrality had to be violated by Germany on strategic grounds," cabled the Kaiser to President Wilson. Military Necessity, the one true god of the Prussian autocracy, demanded the speedy death of France; and to gain the one secure route to the heart of the victim, German honor and Belgian peace were sacrificed on the altar of Prussian militarism.

The Invasion of France

The Advance

Attack on the Liége Gate

On the afternoon of the 4th of August, 1914, there appeared at the mouth of the Liége gateway small bodies of German troops. The first important operation of the great war was to shatter the defenses of this narrow pass and gain admittance to the Belgian plain. The gateway is only a dozen miles in breadth, and the forts of Liége effectively command the railway lines which converge to pass through it before spreading out again on the plain beyond. Evidently the gathering hosts of the Kaiser could not fling themselves over the plain upon France until the advance guard had opened the gate.

A few days later the city was entered, but most of the forts held out; A cavalry screen pushed through the gateway and advanced westward over the plain; but lacking proper support it was forced on the 13th to make a partial retreat before the brave little Belgian army. The battle for the possession of the pass was not yet decided, and in the meantime troops and supplies were congested at the entrance awaiting free passage before the real invasion could seriously commence. The delay was becoming dangerous, for the advantages to be reaped from a sudden sweep over the plain might be lost through failure to gain prompt admission to its level surface. Finally on August 14th or 15th, eleven days after the struggle for the gateway began, the westernmost fort, Loncin, with General Leman, the heroic defender of Liége, fell into German hands and the sweep toward Paris began.

Meanwhile, the French and British were taking advantage of the delay imposed by geographic conditions at the entrance to the plain, in order to prepare for the shock which would quickly follow the debouching of the main German armies through the gateway. Instead of setting themselves athwart the course of the main German advance over the plain, they selected a topographically more favorable position in the northern foothills of the Ardennes. This position possessed at least three notable geographic advantages: it occupied and, therefore, completely blocked the Meuse and Sambre passageways through the Ardennes; it was defended in front by the gorge of the Sambre from Namur to Charleroi, and on the right flank, the flank next the advancing Germans, by the deeper gorge and larger stream of the Meuse; and it flanked the course of the German advance, compelling the invaders to turn and fight on a line selected by the defense, since they could not continue over the plain with their flank constantly exposed to an Allied attack from the hills.

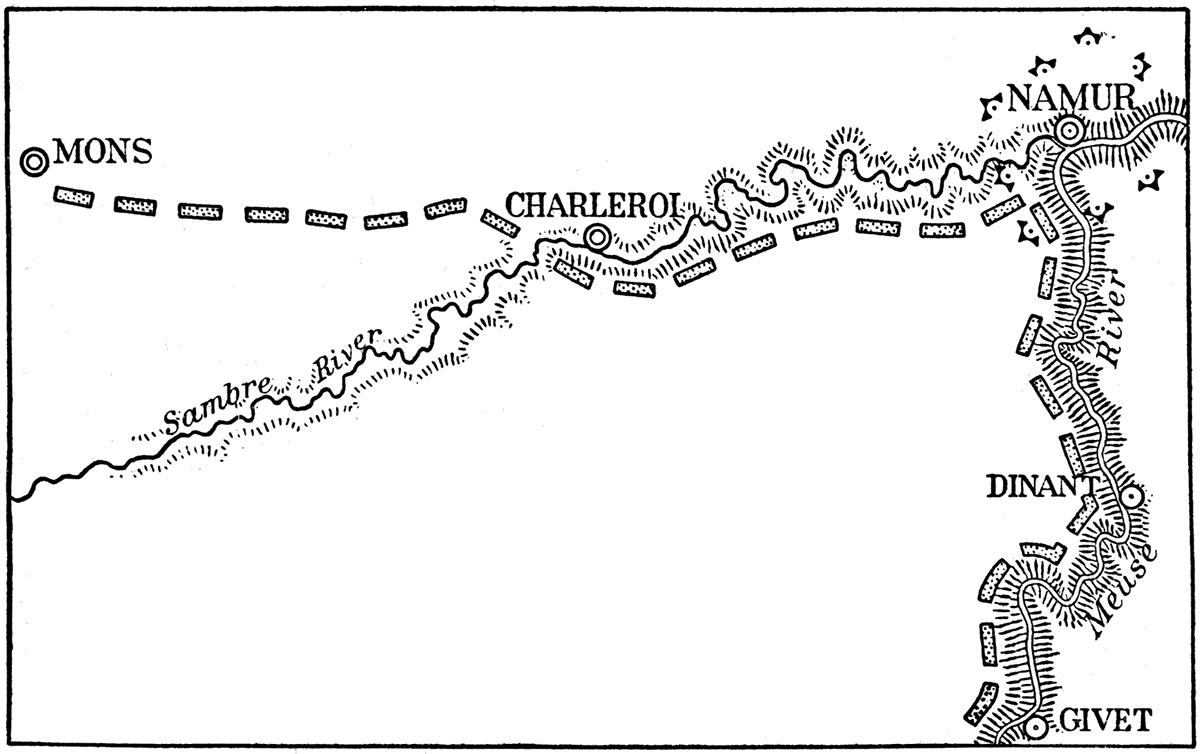

Terrain of the Battle of Mons-Charleroi-Namur

Let us look more closely at this first strategic position of the Allied armies. The main front faced north, and from Mons to Charleroi was constituted by the British Expeditionary Force, while the French Fifth army continued the line from Charleroi to Namur. Unfortunately the British had in front of them no protective topographic barrier of importance; but for all or most of its length the French Fifth army lay behind the gorge of the Sambre. In this portion of its course the Sambre is a strongly meandering river, which follows a winding trench cut 300 feet or more below the upland surface. The flat floor of the trench is 500 or 600 yards in breadth, and covered with open meadows. As a rule the southern wall of the trench is steep and forested. An enemy advancing from the north would, find it difficult to cross the exposed meadows, bridge the river, and dislodge the defenders from the wooded heights beyond.

Figure 6—Main defensive position of the Allied armies at the Battle of Mons-Charleroi-Namur.

With the Allied front facing north along the line of the Sambre, there was, of course, danger of a flank attack by German troops advancing from the east. Fortunately as a protection against this danger the main gorge of the Meuse was admirably located, and behind this natural moat lay the French Fourth army extending from Namur southward past Dinant to the fortress of Givet. This stretch includes the most formidable part of the Meuse trench. Less strongly winding than the Sambre, it is cut deeper below the Ardennes upland and has steeper walls. The river is deeper and broader, and practically fills the bottom of the trench. Precipitous cliffs of bare rock rise in places several hundred feet from the water's edge. Where the slope is less steep the walls are heavily forested. Without question this is the most formidable obstacle in the Ardennes district.

It will be seen that the combined Allied fronts formed a salient with both sides protected by topographic barriers of imposing magnitude, but with the apex thrust far out toward the advancing Germans. This apex being the junction of two principal natural pathways through the mountains, it was the locus not only of an important town, but also of the most valuable crossings over the two rivers. The strategic value of Namur was thus, very great, and for its protection there had been constructed a ring of modern forts. Located at the junction of the north-facing and east-facing Allied armies, and guarding passages across the rivers, which, if captured by the enemy, would enable him to breach both topographic barriers and flank both armies out of their positions, it is clear that fortified Namur was the key to the Allied defense; The fortress was, moreover, the solid support upon which the right of the main Allied front rested in supposed security.

On the 20th of August the German artillery opened fire on the forts of Namur. At the same time the German infantry had wheeled south from the plain to attack the main Allied front behind the Sambre, while the French Fourth army behind the Meuse was also feeling the enemy pressure. It now developed that the Allies had made some fatal miscalculations. In the first place, they had woefully underestimated the enormous strength of the German invasion by the way of the plain. Overwhelming masses of the best Prussian troops were hurled against the Sambre barrier, while the heaviest attacks of all were concentrated on the more remote but topographically unprotected western end of the line. At the eastern end the forts of Namur melted away with incredible rapidity under the German fire. Less than twenty-four hours after they opened fire German troops entered the city, and the next day controlled the vital passages over the Meuse and Sambre. On August 22 the defensive line of the Meuse-Sambre trench was abandoned, and there began the retreat which was not to end till the stage was set for the Battle of the Marne.

The phenomenal sweep of the German armies across the Belgian plain into northern France now proceeded apace. Von Kluck's great army swung far to the west and south, through Tournai, Arras and Amiens, overlapping the western end of the Allied line and constantly threatening to envelop it. The infantry advancing by parallel columns on different roads, and supplied by an efficient motor transport service, moved swiftly over the smooth surface. Ceaselessly pressed by the extreme rapidity of the German advance, the British army withdrew southwestward into France, along the margin of the plain just west of the Oise valley, turning to face more and more toward the northwest in order to defeat Von Kluck's efforts at envelopment. In time this brought the British contingent into a position parallel to the Oise valley, and the heart-breaking retreat was first checked when the exhausted expeditionary force put this important barrier between itself and the pursuing Germans on a line from Noyon to La Fère. Not before this had the plain offered an obstacle sufficiently serious to check the pursuit and afford the pursued a real breathing space. Here was a fairly large river meandering excessively through a series of marshes on the flat floor of a broad valley, with the wooded hills of Noyon protecting the left end of the line and the fortress of La Fère at the right. Although not a defensive barrier of the first importance, it offered temporary security. Meanwhile the French were falling back toward a concave line running from Paris to Verdun, in preparation for the offensive which was to bear the name of the Battle of the Marne.

Thus far the assault through the plain of Belgium had succeeded beyond measure. Germany had moved an incredible number of men at an incredibly swift pace across the low, level pathway into France. The Allied armies were in peril from the swift swing around the western end of their line, and it was believed Paris would soon fall before the heavy guns moving rapidly southward over the plain. Fate seemed about ready to set the final seal of approval upon Germany's choice of the topographically most favorable route into the enemy's country.

The Battle of the Marne

The Plan of Battle

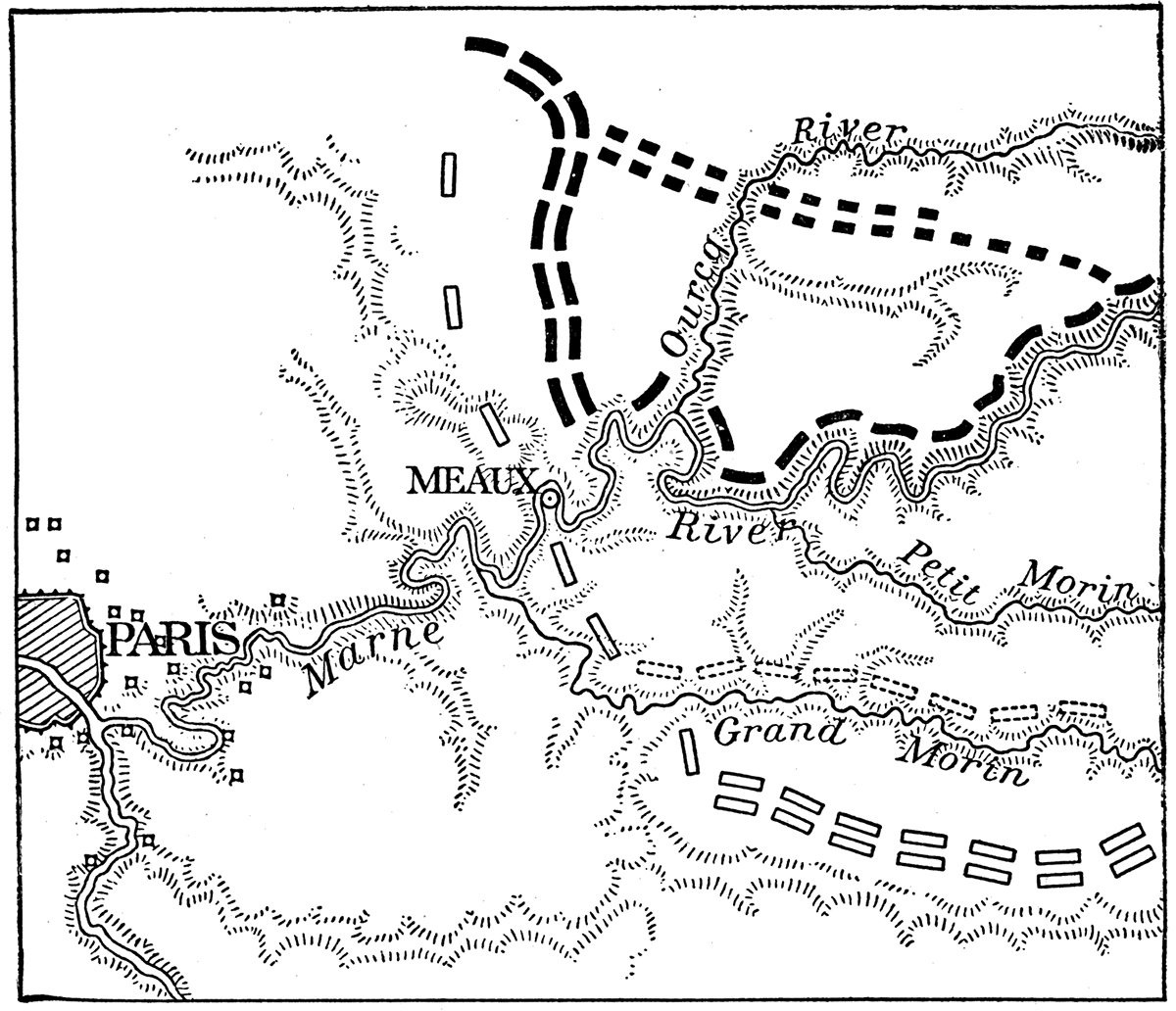

In its simplest terms the Battle of the Marne consisted on the part of the Germans, in an attempt to swing round the western end of the Allied line and envelop it from that direction, at the same time breaking through the Allied center far to the east and forcing the remainder of the western half of the line back on Paris, thereby completing the process of envelopment and creating a second Sedan on a grand scale. On the part of the French the intention was similar: a flanking movement around the west end of the German line, and a break through their center, which should split the invading forces, thus insuring the complete envelopment or precipitate retreat of the western half. It is notable that of these four movements the two flank attacks were begun on the plain north of Paris, while the two attempts to break the enemy's center were staged on the low plain of Champagne. Only subsidiary movements consequent upon the main efforts were assigned to the troops operating over the more difficult topography of the intervening plateau with its deep-cut river trenches.

Let us follow, in outline, the chief events in this most important battle of the war, noting as we go the role played by the surface features of the country over which two vast army groups were contending for a victory which should, in all likelihood, determine the course of world history for many centuries to come. Although called the Battle of the Marne, the trench of this important river cannot properly be said to have played a determining role in the issue of the struggle. Only once, in fact, were the opposing armies aligned on opposite sides of this natural barrier for any great part of its length, and then only for a brief space of time. It was the battle of the plateau of the Marne and of the Marne river and its tributaries, including especially the Ourcq, Petit Morin and Grand Morin; and the final issue was in fact determined on the low plain of Champagne farther east. Maps of the battle line at critical stages in the engagement usually fail to show that striking parallelism between army positions and topographic features which most readily gives one an appreciation of the influence of land forms on military operations. But it would be a serious mistake to draw from this the conclusion that such influence was any the less real.

Joffre's Strategic Retreat to Favorable Terrain

The Battle of Liége gave the Allied armies time to assemble in the triangle guarded by the Sambre and Meuse gorges. The Battle of Moris-Charleroi-Namur, in its turn, was not expected by the Allies to accomplish the impossible task of crushing the German armies, but was designed to afford time for troops to assemble farther south, where the final struggle might take place under conditions more likely to bring decisive victory to the Allied arms. Joffre's strategic retreat not only lengthened out the enemy's lines of communication through many miles of hostile territory, but compelled the German generals to leave behind them enormous forces to guard strategic passes over or through topographic obstacles, to mask fortresses which, like Maubeuge, guarded valley routes into France, and to rebuild bridges over marshes and river trenches. The retreat brought the enemy into the plateau country of the Isle of France, where the east-west gorges would impede the advance, and where the final struggle would take place with these obstacles in the enemy's rear, hampering his supply system and threatening his retreat in case of disaster.

Von Kluck's Enveloping Movement

Swinging west through Belgium and south into France, Von Kluck, with the main striking arm of the German forces, had, by the first week in September, traversed the level plain almost to the gates of Paris. The time had now come, in the opinion of the German high command, for Von Kluck to ignore the small French forces to the west and the exhausted British expeditionary force in front of him, and to strike boldly southeast, get in behind the Allied line east of Paris, and envelop it by a flank attack. The Allied center was already bent in dangerously, and might be broken at any moment. There followed that spectacular sweep of Von Kluck's army from the northern gates of Paris east and south across the Marne, a movement which surprised and puzzled those who looked for no check until the city itself was in German hands. But the destruction of the French army, not the mere occupation of the French capital, was the logical goal of the German general staff; and this goal could only be reached by the envelopment of the enemy's line. This enveloping action was now fully under way.

The French Countermove

The moment had arrived for the French to strike their blow. Within the circle of the Paris forts, and to the west and south of the city, a new French army, the Sixth army, had secretly been assembled. Waiting until Von Kluck had crossed over to the south side of the formidable Marne trench, still patiently waiting until he had also placed the trench of the Grand Morin in his rear, the French Sixth army at length fell on the thin screen of troops he had left west of the Ourcq to protect his flank, and began the process of cutting the lines of communication in his rear. Under pressure the German screen fell back slowly toward the trench of the Ourcq, where they might hope to find protection for a stand against French forces. The army which was seeking to envelop the Allied line was itself in grave danger of being enveloped.

At this point the Germans showed marked skill in turning the obstacles, which might have hampered their retreat, into defensive barriers against the Allied pursuit. How far this was due to failure of the British to press Von Kluck with unrelenting vigor cannot now be stated, but the fact remains that he was able to withdraw his forces north of the Grand Morin, leaving a rear guard of troops along that trench to hold the pursuers at bay, while he sent the bulk of his forces back north across the Marne to retrieve the disaster threatening his exposed right flank. Facing west and southwest against the French Sixth army, Von Kluck began to drive them back. In this new position his left flank was exposed to the British, with only the thin rear guard along the Grand Morin to serve as a protection. For precious hours the Germans tenaciously kept this steep-sided, flat-floored trench between themselves and their foe, while Von Kluck was redressing the balance farther north in favor of the invaders.

Figure 7—Approximate German positions at the battle of the Marne. Solid line open rectangles: Mass of German armies south of Grand Morin, thin screen of troops facing west to protect right flank, at beginning of battle. Broken-line open rectangles: Rear guard defending passage of the Grand Morin while bulk of troops are being shifted north to meet French attack on flank. Black rectangles: Main army facing west and seeking to envelop north end of French line, while screen of troops defends crossings of the Marne trench. Black dots: German armies withdrawing up the valley of the Ourcq.

The Battle for the Marne Trench

At length the British forced the crossings of the Grand Morin and the German rear guard fell back to the Petit Morin and then to the main great trench of the Marne. For a short time this trench now became the most important factor in the struggle. If the German rear guard could hold it some hours longer Von Kluck would be left unmolested to destroy the French Sixth army with his superior forces, the Allied line would be turned, and the war won by the efficiency of a militaristic autocracy. If the British forces could cross the trench without delay they could roll up Von Kluck's left flank and decide the battle, perhaps the war, in favor of the Allied democracies. Great issues hung in the balance along that natural moat on the afternoon of September 9.

Nature gave a clean decision to neither contestant. The obstacle was not sufficient to hold the British in check long enough for Von Kluck to complete the destruction of the French Sixth army. On the other hand, the British found it impossible to cross the barrier at once and involve Von Kluck's flank in disaster. According to reports they negotiated the obstacle first toward its eastern end where it is of smaller dimensions, and only later crossed its western reaches. The delay gave Von Kluck opportunity to swing his forces back toward the Ourcq and withdraw them up that valley, so as to face more nearly south toward the oncoming British.

At this moment there was in progress farther east a phase of the Battle of the Marne in which natural topographic barriers were playing no less important, a role than in the operations just described. If the reader will turn again to the diagrammatic sketch, Figure 1, he will see that the Petit Morin rises in the long east-west belt of the St. Gond marsh, and flows directly west through its gorge in the Marne plateau. We thus have an east-west barrier of no mean importance consisting of a marsh at one end and a river gorge at the other. It was along this barrier that the Battle of the Marne, and hence the issue of the war, was finally decided.

Deadlock at the St. Gond Marsh

While the British were struggling to cross the trenches of the Grand Morin and Marne farther west and assault Von Kluck's flank, the French and German forces faced each other across the St. Gond marsh and the Petit Morin gorge. By September 8 or 9 the French had been able to dislodge the Germans from the north side of the gorge, west of the plateau scarp, and drive them northward in hurried retreat. At the Marne the German armies paused, expecting to check their pursuers with the aid of the imposing river trench; but the impetuous French assaults carried them beyond the northern wall before German reinforcements could be brought up to hold the advantageous position. Farther east, however, the battle line curved southward, and at the east end of the Petit Morin gorge and along the marsh the opposing forces were, for a time, deadlocked. French efforts to push northward across the gorge and occupy the heights beyond were checked, while the marsh remained practically impassable for both armies.

Then began the final German attempt to smash through the French center. The assault progressed successfully across the dry ground beyond the east end of the St. Gond marsh, but back of the marsh and Petit Morin gorge the French line held firm. To increase the force of the blow farther east, the German armies north of the marsh were seriously depleted. At the same time the German line in this vicinity may have been stripped of men to assist Von Kluck out of his troubles farther west. The difficult nature of the marsh was relied upon to protect the weakened German line. The French commander; General Foch, saw, his opportunity. A thin screen of German troops behind the marshy barrier might, indeed, hold that part of their line secure. But Foch could strike with effect close to the east end of the marsh, where a strong German army connected with the thin line back of the obstacle. This junction was a point of weakness, especially when southward progress of the German offensive left an opening here which the depleted forces north of the marsh were unable to close. Here Foch struck with all the fury of the proverbial offensive power of the French army. To get the men for the stroke he withdrew an army corps from behind the Petit Morin gorge, near the edge of the plateau, where the difficult nature of the topography made the withdrawal comparatively safe. The stroke was a brilliant success. The French armies smashed through the gap. The German center was broken, and the German retreat to the Aisne began.

The Battle of the Aisne

The great trench of the river Marne is the most imposing topographic barrier in the plateau of the Isle of France. We should expect that behind its protection the German armies in retreat would make a desperate effort to halt their pursuers. Such, indeed, was the case. But the Marne trench was too close to the field of battle; it was, in fact, as we have seen, involved in one of the principal actions at the west. There was no space to manoeuver, no opportunity so to order the retreat that the retiring forces would arrive at the barrier in such dispositions as would enable them to align themselves along the northern bank without confusion before the pursuers could break across at one or more points and flank them out. The British forced a crossing east of the mouth of the Petit Morin and the French broke through farther east, at a time whim the Germans had retired north of the Marne near Meaux, and were still far south of it in the direction of Epernay. The German line crossed and recrossed the barrier, instead of paralleling it on its northern side. Desperate efforts were made to hold the trench in different sections, but here the French or British broke over with an impetuous assault, there the secure positions were outflanked by crossings made elsewhere. The retreat continued, and the whole valley of the Marne passed into French hands.

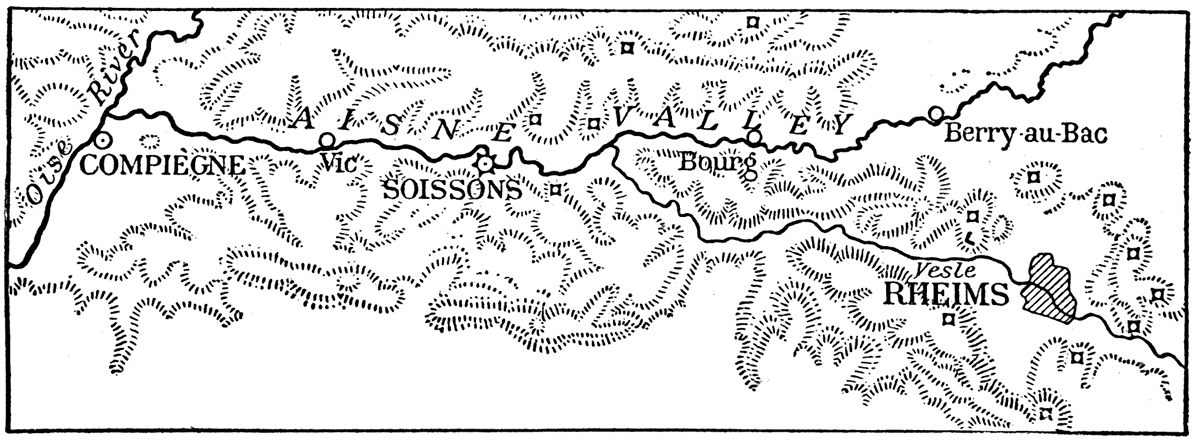

Terrain of the Aisne Valley

Northward there is not a single continuous trench from east to west until the valley of the Aisne is reached. Here, however, is a military obstacle of capital importance. Entering the plateau by a gateway near Rheims, the river flows directly west to join the Oise at Compiègne. For forty miles the great straight trench cleaves the plateau, its steep walls leading abruptly down to a flat floor several hundred feet below, over which the narrow but deep river pursues its meandering course through grassy meadows. In the edge of the plateau above are extensive quarries and vast subterranean galleries and chambers, left by the excavation of a limestone much used for building purposes. Patches of forest clothe the valley walls and are scattered over the upland surface. It was a foregone conclusion that the Germans would make every effort to stop their retreat along this natural defensive barrier.

About the 12th or 13th of September the main German armies arrived at the line of the Aisne, closely pressed by the French and British. Crossing to the north side the Germans destroyed the bridges behind them, and turned to pour a hurricane of steel into the valley. From trenches along the valley walls and on the plateau crest, from open quarry and cavern mouth, from every bit of woodland cover, machine guns and artillery rained death upon the meadows below, where in exposed positions the French and British pursuers worked feverishly to build pontoon bridges and rafts with which to cross the unfordable river. Heavy rains had been falling and the flood waters made the task doubly difficult and dangerous. Every advantage of nature lay with the invader. If he could not stop the pursuit here and hold the rest of northern France in his grip, he could hardly hope to pause again till the hills of the Ardennes had been reached.

Figure 8—Trench of the Aisne river.

From Soissons west to the Oise valley the French crashed against the barrier with an impetuous assault which carried them through the hail of steel and over the flooded Aisne. At the foot of the northern valley wall they paused to regain their breath. East of Soissons to Berry-au-Bac, the British met with less success. Baffled at first by the combined defensive of nature and man, they at length made a few precarious crossings. The morning of September 14 found the French over the stream and ready for an attack upon the steep northern wall of the trench, while the British had attained the northern bank only in places. The situation was not ideal for a further offensive, but time was precious; the odds were becoming greater every hour as the Teutons dug in more and more firmly along their naturally strong position.

An immediate assault on the plateau was ordered. Up the steep valley walls, and out over the plateau to the north swept the invincible Frenchmen. Night found the trench of the Aisne behind them, although the highest crests on the plateau were yet in the hands of the Germans. Farther east the British were still held at bay south of the trench for several-mile stretches east of Soissons and again east of Bourg. The French, unsupported by a corresponding British advance on their right, and with their lines of communication imperiled by a flooded river in their rear, were unable to hold their gains. In a day or two they were pushed back to the river, and the Battle of the Aisne was decided in favor of the Germans. The great moat, made formidable by nature and skillfully fortified by man, had proven too much for the offensive power of the Allied armies. The mobile war in the west was ended, and the war of the trenches had begun.

The Deadlock

The Battle of Nancy

Terrain of the "Grand Couronnè"

While the sweeping movements involved in the Battle of the Marne were in progress in the west, the war of fixed positions was beginning farther east, The Germans massed in the Lorraine gateway were making their first great attempt to smash the outer line of the natural defenses of Paris. As can be seen from the sketch, Figure 1, Nancy guards a double gateway through the easternmost plateau scarp. The crest of the escarpment, a line of heights overlooking the lowland to the east, is known to French military writers as "le Grand Couronnè," Along this crest the main positions of the French armies, under General Castelnau, were located, taking skillful advantage of a topography extremely unfavorable to the Germans. To defeat the French armies and capture the first plateau belt with the Nancy gateways, was the object of the Battle of the Grand Couronnè, or as it is popularly known, the Battle of Nancy.

Not far from 400,000 highly trained German troops were massed on the lower land in the course of the battle, and hurled against the wooded plateau scarp. French infantry in greatly inferior numbers intrenched along the higher levels, and French artillery concealed in folds of the undulating upland ground, in ravines cut back into the escarpment face, and in patches of woodland, poured their combined fire upon the assaulting columns below. In front of the main scarp are outlying mesas and buttes, erosion remnants which, like the positions on the main crest, command a wide field of fire. Wave after wave of the gray-clad invaders in mass formation swept up the lower slopes of the Grand Couronnè, withered away under the merciless hail of steel from the heights above, ebbed back to the lowland again in weakened currents, leaving a gray mark on the plateau face to mark the highest reach of each impotent wave.

The Impregnable Barrier

Day after day the slaughter went on throughout all the first third of September. The myth of German invincibility died hard; the impregnability of Nature's best fortifications, when manned by Frenchmen, was a hard lesson to learn. Forty thousand German corpses at the base of the scarp, one-fourth of the attacking forces on the casualty lists; such were the results of the Kaiser's introductory study of the natural defenses of Paris. Not, however, until he had pondered the bloody chapters of Verdun did he fully realize that the topographic barriers, which he well knew to be difficult, were, as a matter of fact, impregnable.

The Battles of Verdun

First Assault on the Verdun-Toul Scarp

On the 20th of September the German armies made their first serious attempt to break through the Verdun-Toul escarpment. The French line, pivoting on Verdun, swung far to the south on either side. If the eastern limb of the salient, along the plateau scarp, could be broken, the troops defending the western limb would be taken in the rear and Verdun isolated. The eastern limb was held by a comparatively thin line of French troops who depended upon the strength of the topographic barrier to maintain their positions. Occasional permanent forts along the crest added their measure of strength, although the known weakness of such fixed points had led the French to transfer many of the big guns to outlying field fortifications located with regard to the favorable configuration of the terrain.

From the low plain of the Woevre the waves of German troops were hurled westward against the escarpment. The slaughter was terrible, but for a moment German hopes ran high. Some-miles south of Verdun the scarp is broken down by erosion, and through several low passes one may quickly reach the Meuse river. Here the Germans secured a foothold on the eroded plateau, and brought their heavy artillery within range of several of the southern forts. Fort Camp des Remains quickly crumbled to ruins under the rain of heavy explosive shells. The Germans established themselves in St. Mihiel, and threw some forces across, the river. A general assault on the long escarpment had succeeded at the point topographically most favorable to the attacking troops, but had failed elsewhere; There resulted the famous "St. Mihiel salient," which was to persist through several years of strenuous warfare. The partial success of the German armies could not be pushed to victory so long as the more formidable positions of the plateau scarp remained in the hands of the French.

The struggle which will go down in history as "the Battle of Verdun" was not to begin until some months later, when the opposing armies had been long deadlocked in the war of the trenches. Struggles, which in previous wars would have counted as important battles, had shown that Verdun could not be taken except by military operations conducted on a colossal scale. On such a scale Germany prepared for her greatest effort of the war. The accumulations of munitions and the massing of men and guns exceeded anything previously dreamed of. The main attacks were made from the north. Entering the escarpment by the broad open gateway cut obliquely through it by the Meuse river north of the city, the German armies had already spread out on both sides of the valley, occupying cross ridges between some of the east-and-west trending branch ravines. An advance southward across these successive ridges was deemed more feasible than an attack from the east against the main scarp, although operations from that direction should accompany the major movement.