Prev Page--Adjacent Units || Next Page--More on Stratigraphy

Stratigraphy of the Greenhorn Limestone

Lincoln Limestone Member

General Description

The Lincoln Member of the Greenhorn was the first part of the formation to receive a formal name. The unit was originally called Lincoln Marble by Logan (1897, p. 215) and was renamed Lincoln Limestone Member by Rubey and Bass (1925, p. 47). No type section was designated by these earlier workers but the writer (Hattin, 1969) has described as standard reference section the exposure in SE SE sec. 31, T. 12 S., R. 10 W., Lincoln County (Loc. 24) where the member is 24.1 feet thick and is well exposed in a recently excavated road cut.

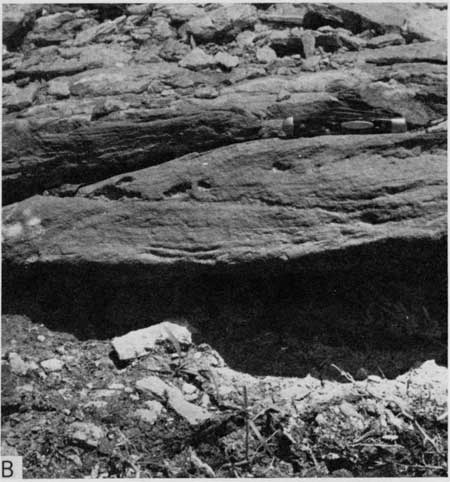

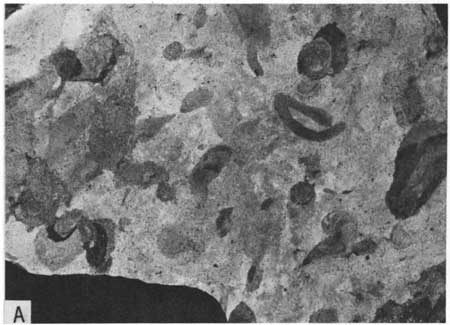

The member consists primarily of shaly chalk through which are scattered numerous, usually thin to very thin beds and lenses of well-cemented skeletal limestone, seams of bentonite, and a few, commonly discontinuous thin beds of chalky limestone. Chalky shale is included in the lower part of the member at a number of localities in north-central and westernmost Kansas. Unconsolidated skeletal sand occurs in the lower part of the member at Locality 24, and hard, fine-grained concretionary limestone occurs near the base of the member at locality 62. In Kansas, thickness of the Lincoln Member ranges from 16.2 feet (Loc. 12) to 33 feet (Loc. 4), averaging 23.1 feet for eleven measurements including two (Locs. 47 & 48; Locs. 16 & 17) that are composites. The lower contact of the member, defined in detail in the foregoing section of this report, is at a widespread unconformity in much of central Kansas but lies within a gradational lithologic sequence in north-central and westernmost Kansas. The top of the Lincoln is designated as the uppermost bed, group of beds and lenses, or zone of abundant lenses of skeletal limestone lying at the upper limit of the interval that is characterized by general abundance of such rock (Fig. 6,A). As thus defined in the area extending from Rush County northeastward to Washington County, the contact lies close to or at a widespread bentonite seam and between 0.12 to 3.9 feet below the more conspicuous, readily identifiable, highly fractured, burrow-mottled chalky limestone marker bed that is designated HL-1 elsewhere in this report and on Plate 1. I have assumed that the first bentonite beneath HL-1 is everywhere the same seam. At most localities a few very thin lenses of skeletal limestone lie above the contact as defined herein and represent the transition between typical Lincoln and typical Hartland depositional environments, but strata lacking conspicuous concentrations of such rock are better assigned to the Hartland Member. At Locality 6, Washington County, the abundance of skeletal limestone decreases gradually upward in the Lincoln so that the contact between the Lincoln and Hartland Member is not defined sharply. Wing (1930, p. 28) recognized this problem and did not separate the two members, referring instead to the combined Lincoln-Hartland interval as the lower Greenhorn shale. At Locality 8, Ford County, Lincoln-like skeletal limestone beds and lenses occur in the Hartland in an interval 13 feet thick, the top of which lies about 13 feet below the HL-1 marker bed, and are apparently equivalent to the upper part of the Lincoln as that member is developed farther to the northeast. However, this 13-foot-thick interval is separated from the main body of the Lincoln by a 25-foot-thick interval consisting of Hartland-like shaly chalk and chalky limestone beds. Paleontologic evidence, discussed below, suggests that in Ford and Hodgeman counties the basal part of the Lincoln is older than farther to the northeast (Hattin, 1965a, p. 44; 1968) and that much of the Lincoln, as developed in the latter area, passes southwestward into a Hartland-like section containing little skeletal limestone except for the 13-foot-thick interval mentioned above. Still father west, in Kearny County (Loc. 12) the top of the Lincoln lies 44.4 feet below HL-1 marker bed. Even at this locality a few very thin beds of calcarenite lie shortly beneath that marker and represent a horizon nearly equivalent to the top of the Lincoln in most of central Kansas, but by original definition of the Hartland (Bass, 1926) these skeletal limestones are included in the Hartland. In Kearny County, most of what is considered as Hartland is chronologically equivalent to Lincoln strata of the middle and northern parts of the central Kansas outcrop. At Locality 12, the top of the Lincoln is a chalky limestone bed that caps the uppermost portion of the part of the section that is rich in beds and lenses of skeletal limestone. Because the Lincoln does not consist predominantly of skeletal limestone, and because use of the term "limestone" does not, in the strict sense, distinguish this unit from overlying parts of the Greenhorn, I recommend that the name be simply "Lincoln Member."

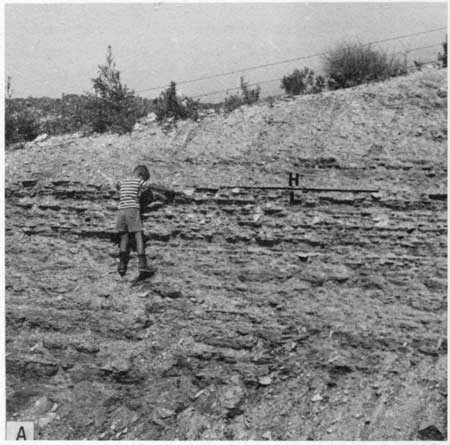

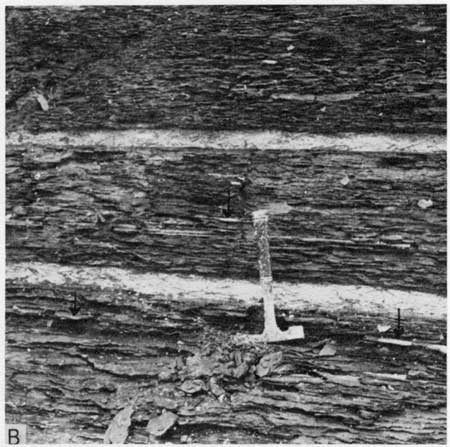

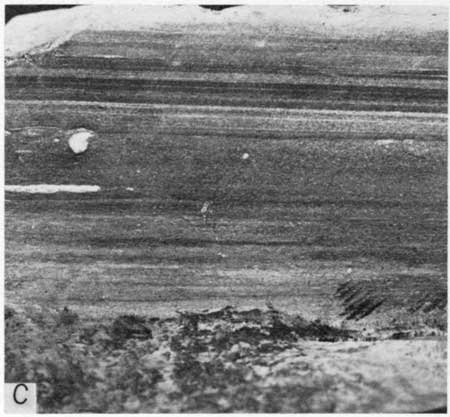

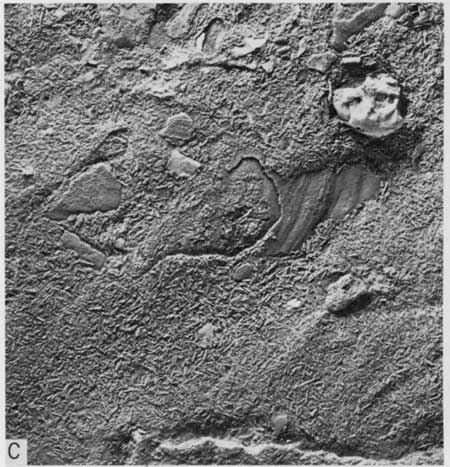

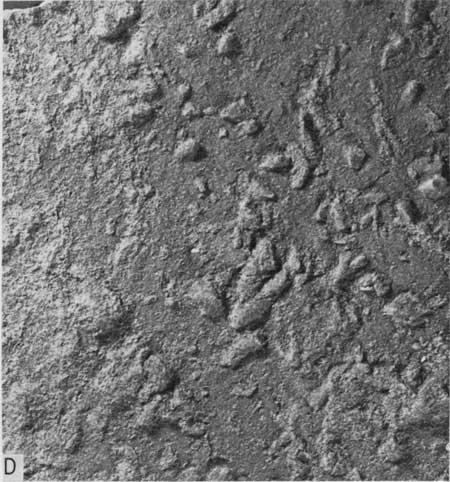

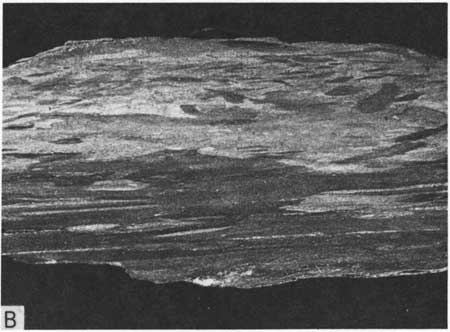

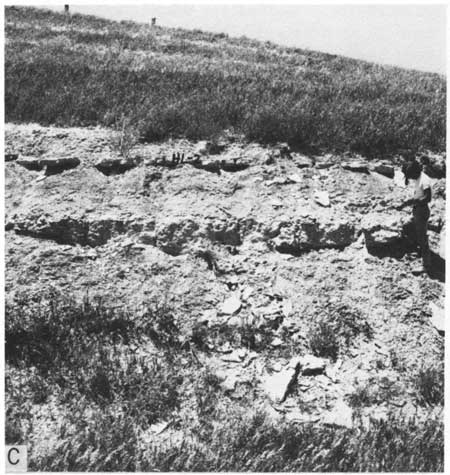

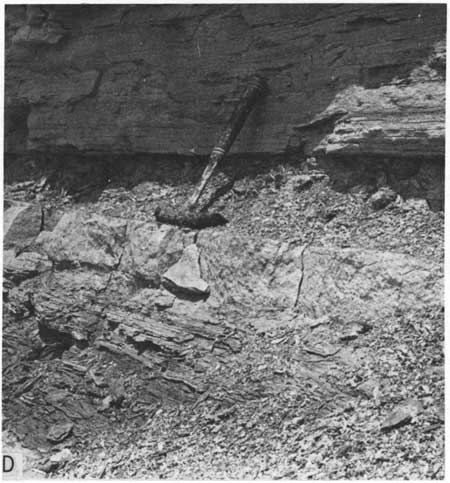

Figure 6--Stratigraphic features of Lincoln Member. A) Lincoln-Hartland contact (horizontal line) 3 miles north of Bunker Hill, sec. 18, T. 13 S., R. 12 W., Russell County (Loc. 3). Note abundance of thin beds and lenses of skeletal limestone at top of Lincoln. B) Typical exposure of shaly chalk in Lincoln Member, sec. 22, T. 6 S., R. 3 W., Cloud County (Loc. 47). C) Specimen of thinly laminated shaly chalk from middle part of Lincoln Member, sec. 18, T. 13 S., R. 12 W., Russell County (Loc. 3). X1. D) Concretionary masses of granular limestone lying 0.5 foot above base of Lincoln Member and on a bentonite seam (arrow), sec. 36, T. 12 S., R. 11 W., Russell County (Loc. 62).

Shaly chalk

The predominant, though not characteristic, lithology in the Lincoln is shaly chalk, which occurs throughout the member (Fig. 6,B). In my detailed measured sections lithic units containing a preponderance of shaly chalk range in thickness from 6.7 feet to as little as 0.1 foot; however, thinner intervals of this kind of rock occur as interbeds in measured units consisting chiefly of skeletal or chalky limestone. Fresh shaly chalk is principally olive black and dark olive gray (5Y3/1), usually drying upon exposure to medium light gray or, less commonly, to medium gray. [Note: These number-and-letter designations are part of a standardized system of rock-color notations (Goddard and others, 1948).] This rock weathers mostly to grayish orange, dark- yellowish orange, or dark yellowish brown and less commonly to other shades of brown and to various shades of gray. The sequence of color changes during weathering is apparently as follows: olive black and dark olive gray → light olive gray → brown → grayish orange → dark yellowish orange. These changes reflect progressive loss of organic matter and oxidation of iron compounds. The highest degree of weathering is apparently reflected in heavily iron-stained chalk of dark yellowish orange color. Limonitized pyrite nodules were recorded in shaly chalk from the basal part of the member at Locality 4 and from a thick shaly unit lying above basal skeletal limestone beds at Locality 59. Fine grained, granular to powdery gypsum is a common weathering product along joints and bedding fractures in many exposures of the Lincoln Member. Most of the shaly chalk is apparently more or less thinly and, generally, evenly laminated (Fig. 6,C) although uneven lamination is common in rock containing an abundance of foraminifera, small shell fragments, or other organic debris. Most of the rock is speckled to a greater or lesser extent by minute (less than 1 mm long), nearly white, oblate spheroidal fecal pellets that are rich in coccolith remains (see Goodman, 1951; Hattin, 1962, p. 40, 106, for prior discussion of such pellets). These pellets are most evident in unweathered rocks and contribute importantly to the laminated character of the shaly chalk. Samples of shaly chalk are generally gritty, owing to presence of calcareous silt and fine sand which ranges widely in abundance. The coarser grains are mostly Inoceramus prisms and tests of planktonic foraminifera, both of which are common in thin sections of shaly chalk (see section on petrography). In fresh exposures the shaly chalk is very tough and tends to break into irregular-shaped blocks, but where even slightly weathered the rock splits readily into innumerable small chips the long dimensions of which lie parallel to bedding. Unlike noncalcareous clayey shales of the Kansas Cretaceous, exposures of shaly chalk remain firm when water soaked.

Shaly chalk lithology is completely gradational with related chalky shale- calcareous shale and nonlaminated chalky lithologies. The gradation with chalky shale and calcareous shale is especially evident in the Graneros-Greenhorn transition at Localities 1, 4, 6, 12, and 47; chalky shale is common in the lower part of the Lincoln at Locality 21, Mitchell County, and at Locality 12, Kearny County. Both calcareous shale and chalky shale are included in the lower part of the Lincoln at Locality 6.

Most shaly chalk units in the Lincoln contain thin to very thin discontinuous beds or lenses, the latter from 0.25 foot to less than 0.01 foot in thickness, of skeletal limestone. These limestones, described below in the section on petrography, range from calcisiltites, composed of Inoceramus prisms and/or tests of planktonic foraminifera, to calcirudites composed largely of oyster and Inoceramus shells or shell fragments, with all possible gradations in between. These skeletal limestones, as well as whole and fragmentary valves of Inoceramus, project from rain-washed surfaces of units containing such structures. The characteristic association of shaly chalk and skeletal limestone is the principal basis for recognition of the Lincoln Member.

Although ranging widely in abundance, nearly ubiquitous fossils in Lincoln shaly chalks include whole and fragmentary valves of Inoceramus prefragilis Stephenson, tests of planktonic foraminifera, and fish scales, bones, and teeth. The Inoceramus valves are generally flattened parallel to bedding. just as invertebrate debris is locally concentrated as lenses or laminae of skeletal limestone, fish remains are likewise concentrated locally, though in far less abundance, and the whole skeleton of a small fish was recorded in shaly chalk of the middle part of the member at Locality 3. Small, cylindrical, white-weathering, brown phosphatic coprolites are a common constituent of the Lincoln shaly chalks but these occur as isolated specimens. Flattened molds of ammonites, especially including forms referable to Eucalycoceras and Desmoceras are common in shaly chalk of the middle Lincoln at Locality 26, and lower part of the Lincoln at Locality 1.2. A few other forms were collected but ammonites are generally uncommon in shaly chalk of the member. Details of Lincoln biostratigraphy are presented in a later section of this report.

Chalk and Chalky Limestone

Every complete exposure of the Lincoln that I examined contains one or more beds, and at some places lenses, of nonlaminated chalk and/or chalky limestone. These are not characteristic of any one part of the member but, where several such beds or groups of lenses occur, tend to be scattered through the section. The more or less continuous units are mostly less than 0.3 foot thick but locally reach 2 feet (Loc. 8). In such lithic units the rock is mostly thin to very thin bedded. Lenses of chalk or chalky limestone range from less than 0.01 foot to as much as 0.5 foot in thickness. Lincoln chalk and chalky limestone is mostly olive gray (5Y4/1, 5Y3/2) to dark olive gray (5Y3/1) where fresh, and usually weathered to grayish orange or dark yellowish orange. Partly weathered rock is light olive gray (5Y6/1). All gradations exist between relatively soft, weakly resistant chalk to hard, well-lithified chalky limestone. Some of the chalky limestones contain thin, generally lenticular concentrations of skeletal debris that is cemented by sparry calcite to form hard calcarenite or calcisiltite. About 10 percent of the chalk or chalky limestone beds examined are at least in part thinly laminated. Unlike similar rocks in the overlying Hartland and Jetmore Members, chalk and chalky limestone of the Lincoln are virtually devoid of burrow structures. Some of the rocks examined contain pyrite nodules, or limonite nodules weathered from pyrite, and some rocks are banded with limonite. The most common fossils in these rocks are fish remains, Inoceramus prefragilis, and Inoceramus fragments, but a few molds of ammonites were collected, including Eucalycoceras sp. B. Some of these rocks contain an abundance of foraminifera or Inoceramus debris and are gradational between pure chalk and skeletal limestone.

At least two major kinds of chalk and chalky limestone are represented. The first is the common variety of very fine grained, relatively coherent rock much like that seen in the overlying parts of the Greenhorn and in the Fairport Member of the Carlile Shale. The second is a soft, granular rock that is invariably associated with bentonite seams and commonly occurs as lenses lying directly above bentonite seams. Excellent examples of the latter type include the following:

- Loc. 3, 1.6 feet above base of Lincoln, discontinuous bed

- Loc. 5, 9.1 feet above base of Lincoln, lenses

- Loc. 6, 9.5 feet above base of Lincoln, lenses

- Loc. 6, 12.2 feet above base of Lincoln, continuous? bed

- Loc. 6, 13.6 feet above base of Lincoln, continuous? bed

- Loc. 6, 20.1 feet above base of Lincoln, lenses

- Loc. 8, 15.5 feet above base of Lincoln, continuous? bed

- Loc. 24, 17.3 feet above base of Lincoln, lenses

- Loc. 47, basal unit of Lincoln, lenses

- Loc. 47, 11.3 feet above base of Lincoln, lenses

At Locality 24 and nearby Locality 62, about 0.6 foot above the base of the Lincoln, are white-weathering concretionary masses of fine-grained crystalline limestone up to 0.4 foot thick and 4 feet across (Fig. 6,D). These also lie on a bentonite seam and are apparently related genetically to the granular chalks tabulated above. In a few places the ordinary variety of chalk or chalky limestone lies on bentonite in the Lincoln, but even these rocks occur mostly as lenses. Most of the lenses of granular chalk associated with bentonite are poorly fossiliferous. It seems an obvious conclusion that such lenses are mainly diagenetic structures possibly resulting from precipitation or recrystallization of calcite by downward-percolating waters that were unable to penetrate a bentonite barrier. In a given section many bentonite seams apparently lack association with such rock, so that the mere presence of bentonite seams was obviously insufficient to produce lenses of granular or ordinary chalk and chalky limestone.

Skeletal limestone

The Lincoln Member is characterized by the abundance of thin to very thin beds and lenses of skeletal limestone. Some of these are chalky, indicating genetic relationship with chalk and chalky limestone through a gradational series from chalk wackestones to grain-supported, spar-cemented skeletal rock. These skeletal limestones range from nearly pure foraminiferal and/or Inoceramus-prism calcarenite or calcisiltite to conglomeratic limestone containing several kinds of coarse skeletal and rock debris.

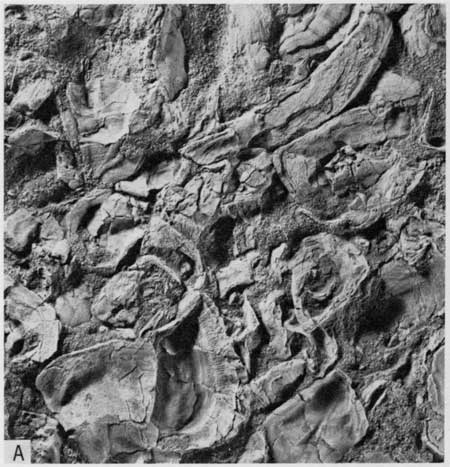

The coarsest-grained rock occurs at or near the base of the Lincoln and is especially well developed at Localities 2, 3, 5, 8, 23, 26, 27, and 69. At Locality 8, the basal bed of the Lincoln is 0.25 foot thick and consists largely of whole and broken valves of Ostrea beloiti together with Inoceramus prisms, bone pebbles, and a few shark teeth (Fig. 7,A). At Locality 23 the lowest 2.5 feet of the Lincoln contains two conglomeratic units. The upper of these is 0.45 foot thick, consists of 3 thin beds of limestone separated by thin interbeds of shaly chalk, and thickens locally to 1.5 feet. This unit consists dominantly of Inoceramus prisms together with abundant small shell fragments and contains small limestone clasts. Where thicker, the rocks in this unit consist mainly of coarse skeletal fragments, valves of Inoceramus, chunks of calcified wood, irregular-shaped pebbles of fine-grained lime- stone, and many large, mostly fragmentary molds of ammonites. The basal conglomeratic limestone at Locality 5 and the conglomeratic rocks at or near the base of the member at the other localities cited above consist principally of Inoceramus prisms, oyster and Inoceramus valves and shell fragments, bentonite pebbles, phosphatic coprolites, fish bone fragments, shark teeth, and quartz sand grains. At a number of other localities, similar rocks lie at the base of the member but are finer grained and not so obviously polygenetic. Most of the conglomeratic rocks in the basal part of the Lincoln consist predominantly of Inoceramus prisms and small fragments of Inoceramus valves and these rocks are thus a variety of rock described below as inoceramite (Hattin, 1962, p. 41). At several places, especially Localities 2, 3, and 69, the conglomeratic rock grades upward into adjacent fine-grained inoceramite. At the localities mentioned, conglomeratic limestone units range in thickness from 0.15 to 1.85 feet in thickness and are unevenly very thin to medium bedded. Some are laminated, and some are cross laminated to cross bedded (Fig. 7,B). At Locality 5 (Ellis County) crossbed data are: strike--N8°E, dip--9° NW; strike--N80°W, dip--17°NE. Data for cross beds in inoceramite at Locality 26 (Russell County) are: strike--N75°E, dip--10°NW; strike--N65°E, dip--14°NW. Cross beds in basal Lincoln inoceramite at Locality 69 are: strike--N18°W, dip--15 to 17°NE. These limited data agree with data on current direction determined by the writer (1965a, p. 53) for the Graneros Shale, namely, that the prevailing current direction in the area between the present Smoky Hill and Saline Rivers was generally toward the north. The conglomeratic limestones described above are mostly hard, brittle, and resistant, but where weathered are crumbly, as at Locality 69. Where freshly broken these rocks have a petroliferous odor.

Figure 7--Stratigraphic features of Lincoln Member. A) Upper surface of coquinoidal limestone lying at base of Lincoln Member, sec. 5, T. 25 S., R. 24 W., Ford County (Loc. 8), showing abundant valves and fragments of Ostrea beloiti. X1. B) Cross-bedded, conglomeratic skeletal limestone at base of Lincoln Member, sec. 18, T. 13 S., R. 12 W., Russell County (Loc. 3). C) Upper surface, parallel to bedding, of skeletal limestone from top of Lincoln Member, sec. 5, T. 25 S., R. 24 W., Ford County (Loc. 8), showing felt-like texture. Principal grains are isolated Inoceramus prisms. X2. D) Lower surface, parallel to bedding, of skeletal limestone from base of Lincoln Member, sec. 4, T. 12 S., R. 15 W., Russell County (Loc. 26), showing convex hyporeliefs believed to be fecal castings. X1.

Most abundant of Lincoln skeletal limestones are the inoceramites, well-cemented rock composed mainly of Inoceramus prisms and commonly containing much coarse skeletal debris, especially valves or fragments of Inoceramus, and, less commonly, oyster valves and fragments, and scraps of fish bones, scales, and teeth. Complete gradation exists between the conglomeratic skeletal limestones at the base of the Lincoln and the predominantly sand-sized inoceramites. Inoceramites composed mostly of Inoceramus prisms have a felt-like appearance (Fig. 7,C) and strongly oriented grains were observed in some such rocks, especially in the basal part of the Lincoln at Locality 26 where aligned prisms lie parallel to the current flow direction as indicated by cross bedding. Some inoceramites consist exclusively of Inoceramus valve fragments that are commonly stacked parallel to bedding or imbricated in the small lenses where these fragments are concentrated. Many of the inoceramites contain tests of planktonic foraminifera, and a complete gradation exists between pure inoceramite and pure foraminiferal limestone. Similarly, a complete gradation exists between sparry calcite-cemented skeletal limestone, chalky skeletal limestones and highly fossiliferous chalk or chalky limestone, but this gradation is more typical of rocks in the Pfeifer Member than in the Lincoln. The inoceramites are scattered throughout the Lincoln, occurring as thin to very thin beds and thin to very thin irregular lenses (Figs. 6,A,B). Some measured units consisting mostly of thin to very thin bedded inoceramite are as much as a foot thick and lie mostly in the lower half of the Lincoln, toward the base of the-member, but at many localities, more or less continuous thin or very thin beds of such rock occur also in the upper half of the Lincoln. Zones of thin to very thin lenses of inoceramite occur throughout the member and the uppermost such zone is regarded as marking the top of the member at several localities. In some shaly chalk units, however, inoceramite lenses are sparse to absent. Thus complete gradation exists between extensive, fairly thick units consisting solely of inoceramite and widely scattered small lenses of such rock. In general, the volume of inoceramite decreases upward in the section but there are many exceptions, especially at Localities 8, 21, and 37. At the last locality, the base of one inoceramite bed near the top of the Lincoln preserves interference ripple marks. Large pararipples with heights up to 0.5 foot and wave length up to 3.5 feet occur in the basal 0.85 foot of the Lincoln at Locality 54. The steep side of these ripples faces nearly east. In 1967 a possible pararipple was observed in the basal Lincoln at Locality 64 but that section is now covered and no directional measurement is possible.

Sparse subaqueous plastic flow structures were recorded in inoceramite near the top of the Lincoln at Locality 3. Many beds and lenses of inoceramite bear well-preserved, elongate-elliptical, convex hyporeliefs believed to be invertebrate fecal castings (Fig. 7,D).

Like the Inoceramus-rich skeletal limestones, Lincoln foraminiferal limestone occurs as thin to very thin beds and lenses. Many of the lenses are pure calcite-cemented foraminiferal rock, with gradation locally to foram-rich chalk or chalky limestone, but thicker, more continuous beds of foraminiferal limestone generally contain at least some Inoceramus remains and other skeletal debris. Foraminiferal limestone commonly occurs as very small lenses or stringers only a millimeter or two in thickness and as little as 2 or 3 cm in width. Collectively these limestones are light olive gray (5Y6/1, 5Y5/2) to olive gray (5Y4/1) where fresh, weathering to pale yellowish brown, pale grayish orange, or other shades of orange and brown. Like the inoceramites, the foraminiferal limestones are scattered throughout the Lincoln, but tend to be more numerous in the upper half of the member. Some of these rocks are thinly laminated, and a few are cross laminated. The beds and thicker lenses may have irregular surfaces, but the very small, very thin lenses are usually quite smooth. Most of these limestones are hard, brittle, and resistant, and project from slopes of rain-washed exposures. A petroliferous odor was detected in many freshly broken samples.

Bentonite

The Lincoln is characterized not only by its rich content of skeletal limestone but also by having a larger number of bentonite seams than other members of the Greenhorn (Fig. 6,B). In the central Kansas outcrop the number of bentonite seams ranges from 9 (Loc. 1) to 16 (Locs. 16, 47 and 48). The difference in number from locality to locality has three explanations. These are:

- Some of the recorded bentonite seams are less than 0.01 foot thick and could be missed during section measurement, especially in exposures that require much ditching.

- Some of the bentonite seams are discontinuous within a single exposure and may not be represented at adjacent localities.

- Some of the bentonites that are included in the Lincoln at one locality are included in either the Graneros Shale or the Hartland Member of the Greenhorn depending upon the selection of contacts in gradational sequences of strata.

At Locality 12, where strata assigned to the Lincoln are believed to be largely older than most of the Lincoln in central Kansas, the member contains only 8 bentonite seams. However, the overlying Hartland, which is believed to be largely coeval with the Lincoln of central Kansas, contains 10 bentonite seams at Locality 13, bringing the total for the combined section to 18 seams. The Lincoln Member contains 12 bentonite seams at Locality 8, Ford County, but here, too, the Lincoln is believed to be largely older than farther to the northeast, and Hartland strata believed to be coeval with much of the Lincoln farther to the northeast contain 13 bentonite seams.

Correlation of Lincoln bentonite seams is difficult. Not only does the number of seams differ from one locality to the next, but thickness and spacing of bentonites range widely, the latter condition possibly reflecting differences in local rates of sedimentation. Usually a few bentonite seams can be traced from a given section to nearby sections, but with increasing distance, such correlations become very tenuous or impossible. Bentonite seams believed to be correlative are so indicated by interconnecting lines on Plate 1.

In a given section different Lincoln bentonite seams may be less than 0.01 foot to as much as 0.5 foot in thickness. Individual seams were observed to range laterally from a featheredge to 0.35 foot in thickness within a few feet. Some are arched over, or downward beneath, adjacent lenses of chalky limestone. Color of fresh or nearly fresh bentonite ranges widely. Most commonly encountered colors, in decreasing order of occurrence, are light olive gray (5Y4/1, 5Y5/2), light gray, yellowish gray (5Y8/1, 5Y7/2) and bluish or light bluish gray (5B6/1, 5B7/1). Each of several other shades of gray, and yellow, and also olive and green, were encountered in one or two places. The normal weathered colors of these bentonites is nearly white, but in most places the weathered rock is stained grayish orange to dark yellowish orange by limonite. Uncommon weathered colors are very pale orange, moderate olive brown, and moderate brown. Lincoln bentonite seams are commonly slightly to moderately silty, although nonsilty to very slightly silty seams also were observed. Minute biotite flakes are sparse to abundant in some bentonite seams at a number of localities. Beds or lenses of granular chalk or chalky limestone associated with bentonite seams have been described above. At a few places, some seams of bentonite are underlain or overlain by seams of vertically prismatic selenite, a common feature of bentonites in other Kansas chalks, especially the Fairport Member of the Carlile and Smoky Hill Member of the Niobrara.

A few powdered samples of Lincoln bentonite were examined by X-ray diffraction techniques and found to consist almost wholly of montomorillonite, with trace quantities of kaolinite and quartz.

Fossils

Biostratigraphy of the Greenhorn is treated in a separate section of this report; however, the various range and assemblage zones are not based on all fossils known from the various members. The following list is a compilation of all macroinvertebrate species recorded during the present study. Appearance in the list does not indicate co-occurrence of species. Starred species are the most common; those marked by a dagger are rare or are known only from a single Greenhorn locality.

| Bivalves: | |

| †Camptonectes sp. (undescribed), one specimen from Loc. 12 | |

| *Exogyra aff. E. boveyensis Bergquist | |

| Exogyra columbella Meek | |

| *Inoceramus prefragilis Stephenson | |

| †Inoceramus cf. I. rutherfordi Warren (late form) | |

| Inoceramus cf. I. tenuistriatus Nagao & Matsumoto | |

| Ostrea beloiti Logan | |

| Gastropods: | |

| †Lispodesthes? sp., single abraded specimen from Loc. 8 | |

| Ammonites: | |

| †Borissjakoceras cf. B. orbiculatum Cobban, crushed specimen from Loc. 12 | |

| Calycoceras? canitaurinum (Haas) | |

| †Desmoceras sp. | |

| †Desmoceras (s.l.) sp. | |

| †Dunveganoceras cf. D. pondi Haas | |

| *Eucalycoceras sp. A. | |

| *Eucalcoceras sp. B | |

| Acanthoceras wyomingense (Reagan) | |

| †Pseudocalycoceras sp. | |

| *Stomohamites cf. S. simplex (d'Orbigny) | |

| Cirripeds: | |

| †Calantica? sp. | |

| scalpellid, sp. | |

| †Stramentum sp. A (undescribed), Locality 3 only | |

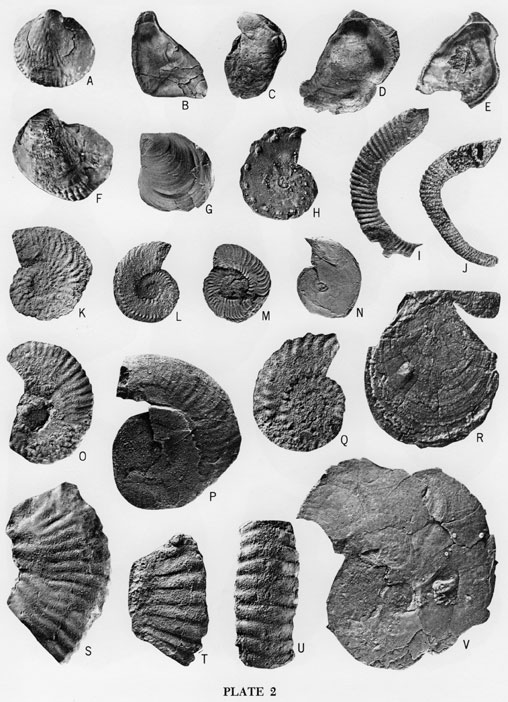

Lincoln macroinvertebrate fossils are illustrated in Plates 2, 3 and 4.

Explanation of Plate 2

Bivalves and ammonites from the Lincoln Member.

A,F, Exogyra columbella Meek: Exterior views of left valves, both X1, KU82083, KU82084, lower part of Lincoln Member at Locality 23.

B-E, Ostrea beloiti Logan: B, interior view of right valve, X1, KU82073, lowermost bed of Lincoln Member at Locality 8; C, exterior view of right valve, X1, KU82074, lowermost bed of Lincoln Member at Locality 8; D, interior view of left valve, X1, KU82072, lowermost bed of Lincoln Member at Locality 8; E, interior view of left valve, X1, KU82071, lowermost unit of Lincoln Member at Locality 28.

G, Inoceramus cf. I. tenuistriatus Nagao and Matsumoto: internal mold of left valve, X1, KU82094, middle part of Lincoln Member at Locality 12.

H, Acanthoceras? sp.: flattened internal mold, X1, KU82099, lower part of Lincoln Member at Locality 12.

I,J, Stomohamites cf. S. simplex (d'Orbigny): I, internal mold, X2, KU82122, lower part of Lincoln Member at Locality 23; J, crystalline-calcite internal mold, X2, KU82081, lowermost unit of Lincoln Member at Locality 3.

K-M, Q, Eucalycoceras sp. B: K, L, latex casts of external molds, K is X2, L is X1, KU82091, KU82090, middle part of Lincoln Member at Locality 26; M, latex cast of external mold, X1, KU82089, lower part of Lincoln Member at Locality 30; Q, internal mold, X2, KU82092, middle part of Lincoln Member at Locality 26.

N, Borissjakoceras cf. B. orbiculatum Stephenson: internal mold, X1, KU82100, lower part of Lincoln Member at Locality 12.

O, S-U, Eucalycoceras sp. A: O, latex cast of external mold, X1, KU82088, middle part of Lincoln Member at Locality 8; S, internal mold fragment, X1, KU82086, lower part of Lincoln Member at Locality 23; T, latex cast of external mold fragment, U, ventral view of internal mold fragment, both X1, KU82087, KU82085, lower part of Lincoln Member at Locality 23.

P, Desmoceras (s.l.) sp.: internal mold, X1, KU82082, middle part of Lincoln Member at Locality 26.

R, Camptonectes sp.: flattened valve, X2, KU82093, lower part of Lincoln Member at Locality 12.

V, Desmoceras sp.: flattened internal mold, X1, KU82189, lower part of Lincoln Member at Locality 12.

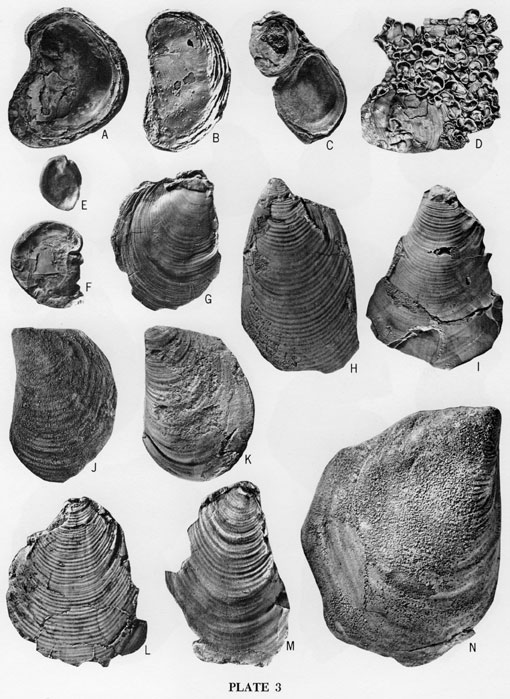

Explanation of Plate 3

Bivalves from the Lincoln Member.

A-F, Exogyra aff. E. boveyensis Berquist: A, interior view of left valve, X2, KU82080, uppermost unit of Lincoln Member at Locality 8; B, exterior view of right valve, X2, KU82078, uppermost unit of Lincoln Member at Locality 8; C, interior view of two left valves, X2, KU82076, lowermost unit of Lincoln Member at Locality 26; D, cluster of valves on Inoceramus, X1/2, KU82077, lowermost unit of Lincoln Member at Locality 26; E, interior view of right valve, X2, KU82075, lowermost unit of Lincoln Member at Locality 5; F, interior view of right valve, X1, KU82079, uppermost unit of Lincoln Member at Locality 8.

G, Inoceramus sp., partially crushed right valve, X2, KU82098, middle part of Lincoln Member at Locality 47.

H-N, Inoceramus prefragilis Stephenson: H, partially crushed internal mold of left valve, X1, KU82102, uppermost unit of Lincoln Member at Locality 8; I, flattened internal mold of left valve, X1/2, KU82107, lowermost unit of Lincoln Member at Locality 26; J,N, internal molds of left valve (J) and right valve (N), both X1, KU82096, KU82152, middle part of Lincoln Member at Locality 8; K, internal mold of left valve, X1, KU82097, basal unit of Lincoln Member at Locality 40; L, flattened internal mold, X1, KU82186, Graneros-Greenhorn transition beds at Locality 12; M, flattened internal mold of right valve, X1, KU82095, middle part of Lincoln Member at Locality 26.

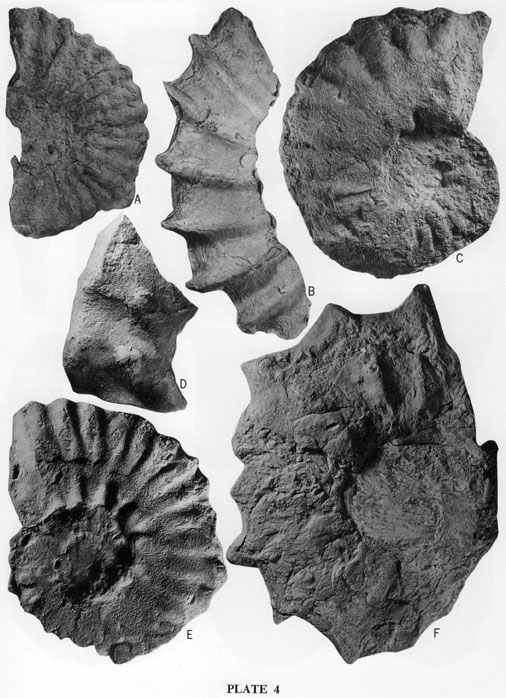

Explanation of Plate 4

Ammonites from the Lincoln Member.

A,C, Calycoceras? canitaurinum (Haas): A, internal mold fragment, X1/2, KU82105, basal unit of Lincoln Member at Locality 3; C, internal mold, X1/2, KU82104, basal unit of Lincoln Member at Locality 61.

B, Dunveganoceras cf. D. pondi Haas: latex cast of external mold fragment, X1/2, KU82103, basal unit of Lincoln Member at Locality 61.

D,F, Acanthoceras wyomingense (Reagan): D, internal mold fragment, X1/2, KU82153, lower part of Lincoln Member at Locality 23; F, internal mold, X1/2, KU82106, basal unit of Lincoln Member at Locality 69.

E, Pseudocalycoceras sp.: internal mold, X1, KU82101, lower part of Lincoln Member at Locality 23.

Specimens of Inoceramus are represented almost exclusively by isolated prisms, whole valves, or valve fragments representing only the calcitic, prismatic shell layer. The originally aragonitic nacreous layer is preserved only rarely in calcareous shale or chalky shale transitional from the Graneros to the Lincoln and nearly everywhere assigned to the former unit. Weathered limestones from the lower part of the Lincoln commonly contain molds from which the prismatic layer has been partially or wholly exfoliated. Lincoln oysters are preserved almost entirely as calcitic valves or valve fragments and are abundant only in skeletal limestones. The sole specimen of Camptonectes is a flattened, calcitic valve from shaly chalk in the upper half of the member. The only gastropod collected in the Lincoln may have been reworked from the Graneros Shale and is a single abraded conch collected from an Ostrea beloiti coquina lying at the base of the member at Locality 8. Ammonites from the Lincoln are known almost entirely as internal and external molds. These are most common in skeletal limestones, sparse in chalky limestones, and least common in shaly chalk. Specimens in skeletal limestones are commonly little compacted; those in other kinds or rock have been more or less flattened by compaction. The cirripeds are mostly preserved as isolated, calcitic valves in skeletal limestones. At Locality 3, many articulated, calcitic specimens were collected from a small area on a single bedding plane in shaly chalk lying near the middle of the Lincoln.

The number of Lincoln macroinvertebrate species observed in mutual association is everywhere small, nowhere exceeding 8 species. Even where that number occur together, some of the species are pelagic forms, i.e. ammonites and possibly some or all of the cirripeds. This suggests that bottom conditions were generally hostile. Detailed discussion of paleoecology and depositional environments is presented in another section of this report.

Hartland Shale Member

General Description

The Hartland Shale Member of the Greenhorn was named by Bass (1926, p. 69) for "calcareous shale 23 feet thick that is almost devoid of limestone and contains numerous layers of bentonitic clay . . ." and lying between the Lincoln Member and the overlying Bridge Creek. [Note: Hartland was a small town located 6Y2 miles southwest of Lakin, Kearny County. Although the name still appears on maps of the area, There is no longer a town.] Although no type section was designated specifically, Bass (1926, p. 69, 70) gave a generalized description of a section located halfway between Sutton, Kearny County and Kendall, Hamilton County noting that the section there contains a few lenses of dark gray fossiliferous limestone. [Note: Sutton consists of a labeled siding on the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad.] The exposure in NE sec. 32, T. 21 S., R. 38 W., Kearny County (Loc. 13) is designated as the type section because it is probably the one described by Bass. Because the only practicable boundary between the Lincoln and Hartland members is based on concentration of thin beds or lenses of skeletal limestone, the contact in the type section must be placed stratigraphically lower than indicated by Bass. As redefined here, the type Hartland is 44.5 feet thick. Strata included in the Lincoln by Bass, and here transferred to the Hartland, contain little, if any, skeletal limestone. The upper contact of the Hartland is placed at the base of the lowest of numerous, closely spaced, conspicuous hard beds of chalky limestone that characterize the Jetmore Member in central Kansas (Fig. 2,B; 8,A) and Bass' Bridge Creek Limestone Member of Kearny and Hamilton counties. This contact is diachronous as explained below, with burrow-mottled chalk beds of the upper Hartland in central Kansas passing southwestwardly to Hodgeman County, then westwardly to Kearny and Hamilton counties, into hard chalky limestone beds that resemble those of the central Kansas Jetmore.

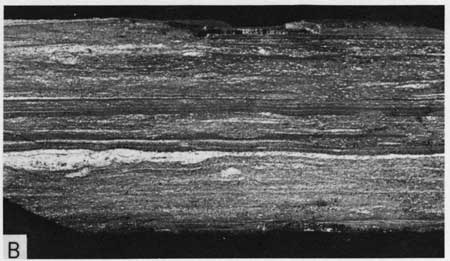

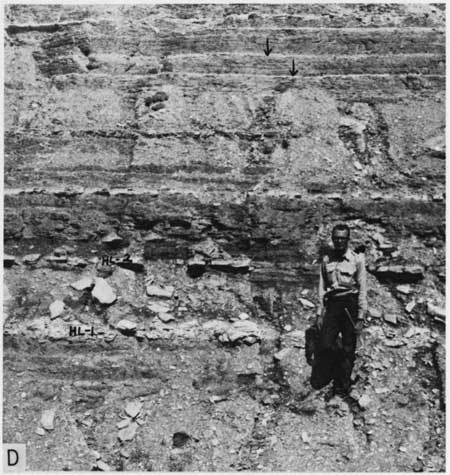

Figure 8--Stratigraphic features of the Hartland Member. A) Hartland-Jetmore contact (arrow), sec. 14, T. 9 S., R. 5 W., Ottawa County (Loc. 45). Reentrant beneath limestone bed at base of Jetmore is caused by weathering of thin bentonite seam nearly at top of Hartland Member. At this locality shaly chalk in upper part of Hartland has been hardened by weathering. B) Specimen of thinly laminated shaly chalk from upper part of member, sec. 18, T. 13 S., R. 12 W., Russell County (Loc. 3). X1. Light-colorled laminae composed mostly of planktonic foraminiferal tests. C) Shaly chalk bedding plane showing scattered, broken fragments of Inoceramus from middle part of member, sec. 32, T. 24 S., R. 38 W., Kearny County (Loc. 1.3). X2. D) Exposure of lower half of Hartland Member, sec. 18, T. 13 S., R. 12 W., Russell County (Loc. 3), showing scattered beds of chalky limestones and thin layers (arrows) of nonlaminated chalk. Marker beds HL-1 and HL-2 are labeled. Note highly fractured nature of HL-1.

In central Kansas the Hartland ranges in thickness from 8.6 feet at Locality 20, Jewell County, to approximately 68 feet in Ford and Hodgeman counties, averaging 26.6 feet for 14 measured sections of which that in the latter area is a composite of Localities 8, 9, and 11. The wide range of thickness is explained in part by the diachronic nature of the Lincoln-Hartland contact mentioned above, and partly by condensation of the section in Ottawa, Mitchell, Cloud, and Jewell counties where, with one exception, all of the principal marker beds are present but where member thickness is only about half that in counties lying directly to the south.

The Hartland does not consist of "shale" in the usual sense of the term, i.e., fissile clayey rock, nor does shaly chalk, the main type of rock, serve to distinguish this unit from adjacent members. Therefore it is suggested that the name be amended to simply "Hartland Member." Because the unit consists largely of nonresistant rocks the member is a slope former. Natural exposures are common at the bases of cliffs held up by the resistant limestones of the overlying Jetmore Member (Fig. 2,A).

Shaly chalk

As in the Lincoln Member, the Hartland consists chiefly of shaly chalk which, in sections measured by me, occurs in depositional units having thickness as little as 0.1 foot to as much as 11.1 feet. The fresh rock is mostly olive black or dark olive gray (5Y3/1), less commonly olive gray (5Y4/1), and dries to medium light gray. Partially weathered rock is mostly light olive gray (5Y6/1, 5Y5/2) or one of several shades of yellowish brown, or light- to very light gray. Where extensively weathered the shaly chalk is mainly grayish orange, very pale orange or pale grayish orange (10YR8/4) and is commonly stained yellowish orange by iron oxide. Other weathered colors include various shades of orange, yellowish gray (5Y7/2, 5Y8/1), pinkish gray, and pale yellowish brown. These colors exhibit all possible gradations. Nearly all of the shaly chalk is tough and breaks into irregular-shaped blocks where freshly ditched. After short exposure the rock breaks more or less parallel to bedding to form small chips. Weathered rock is soft and characteristically separates readily along laminations. Nearly all of the rock is thinly laminated (Fig. 8,B); the laminae are mostly even, but very irregular where the rock contains an abundance of foraminiferal tests. As in the Lincoln Member, most of the shaly chalk contains much calcareous silt or fine sand and is generally speckled by vertically compressed, nearly white, oblate spheroidal fecal pellets. Many of the shaly chalk units contain thin zones of nonlaminated, burrow-mottled chalk. Such chalk, and genetically related chalky limestone beds that were measured separately, is described in detail below. Some shaly chalk units contain very thin lensing beds or lenses of skeletal limestone like that characterizing the Lincoln Member. Most of these lenses lie in the Lincoln- Hartland transition interval, but skeletal limestone occurs also much higher in the section, even within the uppermost shaly chalk unit at some localities (e.g. 1, 2, 3, 13, 20). Hartland shaly chalk units locally contain thin streaks of ferruginous matter or granular gypsum. These may mark the position of very thin seams of bentonite that are now so weathered as to escape detection. In a few places shaly chalk lying adjacent to bentonite seams is waxy and less calcareous than usual. Such rock reflects dilution of calcareous mud by volcanic ash that has been altered to clay. Examples are mentioned below in the section on bentonite.

Hartland shaly chalk units are notably deficient in diversity of fossils. The only ubiquitous large invertebrates are species of Inoceramus. I. prefragilis ranges through most of the member and, in the central Kansas region, Mytiloides labiatus (Schlotheim) occurs in the upper few feet of the member. These fossils are represented by flattened, disarticulated valves and shell fragments (Fig. 8,C) that are locally so abundant as to litter the slopes with debris, but in some units these fossils are rare. Fish remains, including bones and bone fragments, teeth, and scales are present in most units and abundant locally. Valves of Syncyclonema? are abundant on some bedding planes at Localities 9 and 13. Rare specimens of Phelopteria have been collected from just below the middle of the member in central Kansas. Tests of planktonic foraminifera are distributed throughout the Hartland, commonly in sufficient abundance to cause a rough-textured surface on planes of fissility or to form thin lenses or laminae in the rock (Fig. 8,B). Rare molds of acanthoceratid ammonites and a few burrow structures comprise most of the remaining shaly chalk fossils.

Chalk and Chalky Limestone

Chalk or chalky limestone beds are distributed unevenly throughout the Hartland Member (Fig. 8,D). Such beds are as little as 0.05 foot to as much as 1.0 foot thick. Some of these beds pinch and swell within a single exposure, in some places expanding locally to two or three times the usual thickness. Some chalk or chalky limestone layers are discontinuous, and a few consist of widely spaced lenses. Nearly all of these rocks contain one or more types of discrete burrow structures and many are extensively mottled (Fig. 9,A). Shaly chalk directly adjacent to the chalks and chalky limestones is also more or less burrowed, with maximum density of such structures coinciding with the latter rocks. Lack of lamination in all but a few such beds suggests that lithologic homogeneity in the chalk and chalky limestone lithologies has resulted from burrowing activities of a mobile infauna (Hattin, 1969a; 1971). Laminations, usually faint or poorly developed and generally not extending throughout the bed, were observed in chalk and chalky limestone beds at a few localities. Such laminations are not restricted to a particular bed, but are more common in the lower part of the Hartland at Localities 8 and 13 than elsewhere in the section. Where laminated, these rocks contain few or no burrow structures. Complete gradation exists between shaly chalk, chalk, and chalky limestone lithologies. Contacts of the burrowed units are commonly gradational (Fig. 9,B), especially between shaly chalk and soft chalk units, but in weathered sections the chalk and chalky limestone beds are usually well defined with upper and lower surfaces apparently in sharp contact with adjacent shaly chalk. The chalk beds are generally soft, nonresistant, and generally thin; the chalky limestones range from relatively hard to very hard, resistant beds that project conspicuously from surfaces of rain-washed exposures. Some of the chalky limestone beds become soft and crumbly upon weathering and one bed, designated HL-1, tends to shatter irregularly, even where freshly exposed (Fig. 8,D).

Where fresh these rocks are most commonly olive gray (5Y4/1) or light olive gray (5Y6/1 in color. Dark olive gray (5Y3/1), olive black, or medium-dark to very light gray coloration is uncommon. In some exposures the latest-formed chalk-filled burrow structures are noticeably darker in color than the surrounding rock (Fig. 9,B). These rocks dry to light-gray or very light gray. Partially weathered rock is yellowish gray (5Y8/1) or less commonly, moderate yellowish brown. Where extensively weathered these rocks are usually grayish orange, pale grayish orange (10YR8/4), or very pale orange, and less commonly pale yellowish brown, yellowish gray (5Y7/2) or other light shades of yellow and orange. A majority of the chalk and chalky limestone units consist of a single massive bed, but some consist of two or more thin to very thin irregular beds. Where weathered, many of these units become slabby, often breaking apart so as to litter the underlying slopes with small rock chips. Most of these rocks are dominantly micrograined, but some consist largely of planktonic foraminifera and these have coarser texture. Inoceramus prisms are locally a prominent constituent in chalky limestone, as for example, in marker bed HL-1 (see Pl. 1) at Locality 29. Weathered surfaces of chalk and chalky limestone beds are commonly studded with foraminifera, especially those beds lying above the marker referred to in this report as HL-3, but markers HL-1, and HL-2 are also rich in foraminifera locally. Lenses of chalk or chalky limestone rich in forams lie 1 to 3 feet below HL-1 at Localities 3, 5, 11, and 34. These may be related genetically to one another. Maximum development of foraminiferal chalky limestone at that horizon is at Locality 34 where a flat-topped lens of such rock is 2 feet thick and 23 feet wide (Fig. 9,C). The lens is broadly convex below and gently cross laminated, the whole recording a rare episode of large-scale scour and fill on the sea floor during Hartland deposition. At Locality 11 a conspicuous, lensing bed of chalky limestone from 0.5 to 1.0 foot in thickness and lying 0.7 foot below marker bed HL-1 contains conspicuous thin laminae composed largely of planktonic foraminiferal tests.

Figure 9--Stratigraphic features of Hartland Member and equivalent part of Bridge Creek Member. A) Burrow-mottled chalky limestone, cut parallel to bedding, from lower part of Hartland Member, sec. 10, T. 23 S., R. 23 W., Hodgeman County (Loc. 11). X1. Note that last-formed (cross-cutting) structures are of darker color than the others. B) Gradational contact between laminated, little-burrowed shaly chalk and lighter-colored, highly burrowed, chalky limestone from Hartland equivalent of Bridge Creek Member, sec. 22, T. 23 S., R. 42 W., Hamilton County (Loc. 14). Cut normal to stratification. X1. C) Lens of foraminiferal chalky limestone in Hartland Member, sec. 2, T. 14 S., R. 8 W ., Ellsworth County (Loc. 34), resulting from localized episode of scour and fill. Note resistant marker bed HL-2 at level of Dick Schuman's head. D) Hartland marker bed HL-3 (beneath hammer head) and superjacent seam of bentonite, sec. 27, T. 6 S., R. 9 W., Mitchell County (Loc. 63). Note thinly laminated character of overlying shaly chalk.

Many of the Hartland chalk and chalky limestone beds are speckled by the same kind of nearly white, spheroidal fecal pellets as characterize the intervening shaly chalk beds. Burrowing activities of a highly mobile infauna may have contributed to less uniform preservation of these pellets as compared to adjacent non-burrowed shaly chalk beds. Pellets are commonly more apparent in well-preserved burrow structures than in the surrounding rock, possibly because last-formed burrows are, in many places, of darker color than adjacent rock, and the pellets stand in marked contrast to the dark burrow fill.

Other than burrows, chalk and chalky limestone beds nearly all contain valves or molds of Inoceramus, most of which lie essentially parallel to bedding. Some of these valves are fragmentary, but large concentrations, or lenses, of such debris were recorded. Marker beds referred to as HL-1 and HL-2 (see Pl. 1), as well as a nearly equally widespread chalk or chalky limestone bed lying shortly above HL-2 contain elements of the most diversified fossil assemblage in the Greenhorn of Kansas, i.e., the Sciponoceras gracile (Shumard) assemblage. This contains numerous species of ammonites, 7 mostly rare species of pelecypods, a gastropod, a brachiopod, and sparse borings of acrothoracian cirripeds. In the upper part of the member, above marker bed HL-3, a few molds of Tragodesmoceras and Watinoceras have been collected from beds of chalk or chalky limestone.

In chalk or chalky limestone beds some burrow structures are partially or wholly filled with coarsely crystalline sparry calcite and/or pyrite, some of which has been oxidized to limonite in weathered beds. Locally, such rocks contain irregular-shaped blebs or nodules of pyrite or marcasite and, in weathered beds, limonitized remains of such nodules. At several localities in central Kansas, especially Localities 1, 3, and 5, the first widespread chalky limestone bed above HL-2 contains molds of Phelopteria, Baculites, and Calycoceras that are commonly enveloped by a thin black film that possibly represents the remains of organic matter contained in the original shell.

Marker Beds

Among the chalky limestone beds of the Hartland Member are three which can be traced widely and serve as useful marker beds. For convenience these have been assigned the alphanumeric code designations (ascending) HL-1, HL-2, and HL-3 which will be used throughout this report.

Marker bed HL-1 is the thickest chalky limestone in the Hartland (Fig. 8,D). In the area of central Kansas lying between Washington and Rush counties the bed lies 0.91 (Loc. 20) to 11.68 (Loc. 5) feet above the top of the Lincoln Member, this interval generally increasing towards the southwest. The interval increases from 10 feet in southeastern Rush County (Locs. 15, 17) to approximately 40 feet in Ford County (Loc. 8) owing to lateral change of lithofacies whereby the middle and upper parts of the Lincoln pass southwestward into rocks assigned in this report to the Hartland Member, as explained above in the section concerned with the Lincoln-Hartland contact. At Locality 8, only a small part of this 40-foot interval contains an abundance of skeletal limestones, the uppermost beds of such rock lying approximately 9 feet below HL-1, or very nearly the same horizon as the top of the Lincoln Member in Rush County. This westward change of facies is virtually complete at Locality 13 in Kearny County where the interval from top of Lincoln to base of HL-1 is 44.4 feet thick and contains almost no skeletal limestone. At locality 13, however, HL-1 is the basal bed of the Bridge Creek Limestone Member and beds equivalent to most of the central Kansas Hartland are represented by the lower 24 feet of the Bridge Creek Limestone Member.

In central Kansas marker bed HL-1 ranges in thickness from 0.4 foot (Locs. 1 and 68) to 0.9 foot (Loc. 6), averaging 0.56 foot for 14 measurements. In western Kansas the marker is 1.25 foot thick at Locality 13 (Kearny County) and 1.33 foot thick at Locality 14 (Hamilton County) where it is separated into two beds by a 0.13-foot-thick layer of shaly chalk. At nearly all exposures examined, including a large number not measured, this bed is extensively fractured (Fig. 8,D) and under the hammer shatters readily into sharp-edged slabs. The bed is everywhere rich in trace fossils, characteristic among which are threadlike, limonite-stained burrows named Trichichnus by Frey (1970, p. 20), Chondrites Sternberg, and cylindrical, non-branched, smooth-walled burrows 2 to 5 mm in diameter that are filled usually by pyrite, limonite, or calcite. Large-sized, chalky, limestone-filled, burrow structures referable to Planolites Nicholson are abundant, but not diagnostic. This marker is the lowest Greenhorn unit containing faunal elements of the Sciponoceras gracile Assemblage Zone, the full contents of which are discussed in the section on biostratigraphy.

Marker bed HL-2 lies anywhere from 1.1 (Loc. 6) to 2.5 feet (Loc. 11) above HL-1. The former is well developed at every Hartland exposure examined except that at Locality 20 where the normal stratigraphic position of HL-2 is occupied by 0.2 foot of dusky yellow to dark yellowish orange clay, the marker bed apparently having been removed there by intrastratal solution. At Locality 48 the bed is present but discontinuous. These two areas of abnormality may be related to factors which resulted in a condensed stratigraphic interval extending from HL-1 through the lower part of the Jetmore Member in the Jewell and Cloud counties area. Despite the drastic, localized thinning of this interval, every marker bed is present with the single exception of HL-2 at Locality 20. Overall sedimentation rates were obviously lower along a line from Randall, Jewell County, to just south of Concordia, Cloud County, and for a short distance on either side of this line, than elsewhere in the State, perhaps owing to slight shallowing of the sea in this area. This suggestion is supported by the unusual presence in this area of skeletal limestone lenses in the upper part of the Hartland at Locality 20 and between markers HL-1 and HL-2 at Locality 46.

Disregarding very localized discontinuity in an otherwise continuous bed, marker bed HL-2 exhibits its maximum and minimum thickness of 0.2 and 0.6 foot at Locality 6. Such wide range at a single locality is not common, and is largely the result of small areas of downward expansion of the bed. Normal thickness at Locality 6 is about 0.35 foot. Similar downward expansions to 2 or 3 times the normal thickness were observed at Localities 3 and 15. Not including local discontinuity and local downward expansions, the bed averages 0.28 foot in thickness for 14 measurements. This bed contains all but two of the species associated with the Sciponoceras gracile assemblage of Kansas, and is characterized by in-the-round preservation of highly inflated valves of Inoceramus prefragilis specimens. Nodules of pyrite, or their limonitized counterparts were observed locally, but in the Hartland are not unique to this bed, and a pyritized specimen of Inoceramus prefragilis was observed at Locality 3. This bed contains many burrow structures, the most common of which are slender, smooth-walled, mostly calcite-filled, nonbranched cylindrical forms, and large, branched, chalky-limestone filled burrows assignable to Planolites. The most striking attribute of this important bed is its remarkable resistance to weathering. Although relatively soft and subject to platy fracturing where freshly uncovered, this marker hardens upon exposure to become one of the most resistant beds in the entire formation (Figs. 8,D; 9,C). Slabs of this hard, brittle rock commonly litter slopes below a small bench held up by the bed. Marker bed HL-2 is readily recognizable by its highly diversified fauna, the abundance of well-preserved Inoceramus prefragilis valves, the hardness and resistance to erosion, and its proximity to the equally distinctive HL-1 marker. The thin shaly chalk interval separating these two beds contains a conspicuous seam of bentonite that ranges from 0.12 to 0.71 foot in thickness and lies only 0.3 to 0.7 foot above HL-1. Approximate parallelism of HL-1, HL-2 and the intervening bentonite over an extraordinarily long distance (at least as far west as Pueblo County, Colorado) together with remarkably uniform lithology over much of the Kansas outcrop, suggests that the two limestones lie parallel to isochrones. It is simpler to account for slight differences in intervals separating the bentonite from the two limestones at various localities by assuming differential sedimentation, which can be demonstrated in several parts of the Greenhorn section, than to suggest that these thickness differences reflect diachronism of the two marker beds. A full discussion and interpretation of apparently time-parallel burrow-mottled limestone beds in the Hartland, Jetmore, and Bridge Creek Members has been published elsewhere (Hattin, 1971).

I have chosen these limestones as marker beds, rather than the adjacent bentonite seam because the latter could not be identified consistently were it not for the association with the two limestones. The three beds together comprise a clearly recognizable group of markers that in Kansas cannot be mistaken for any other part of the Greenhorn section.

In central Kansas, marker bed HL-3 lies 1.85 feet (Loc. 48) to 5.5 feet (Loc. 15) above HL-2, this interval thickening generally toward the southwest (see Pl. 1). From Locality 15 the interval thins to approximately 4.7 feet at Locality 8, Ford County, thence maintaining uniform thickness westward to Hamilton County where the interval is 4.8 feet thick at Locality 14. At Locality 20, Jewell County, HL-3 lies only 1.0 foot above the clayey deposit representing the position of HL-2, but the original distance between HL-2 and HL-3 is unknown.

Marker bed HL-3 ranges from 0.2 to 0.45 foot in thickness, averaging 0.32 foot for 12 measurements. Except at Locality 14, Hamilton County, where the unit is brittle chalky limestone, HL-3 is generally soft, burrow-mottled chalk that is in most places rich in tests of planktonic foraminifera and that crumbles readily upon exposure to weathering. Ready recognition of the bed is afforded by association with a prominent, overlying seam of bentonite that ranges from 0.25 to 0.6 foot in thickness, averaging 0.46 foot for 18 measurements, and that is nearly everywhere thicker than any other bentonite seam in the Greenhorn of Kansas (Fig. 9,D). The top of this bentonite is only 4.28 feet below the base of the Jetmore at Locality 20, Jewell County, but this interval thickens northeastward to 6.0 feet at Locality 6 and southwestward to 18.7 feet at Locality 15, Rush County. From Rush County this interval thins southwestward to 16.7 feet at Locality 51, Ford County, thence thinning further to only 14.8 feet at Locality 14, Hamilton County where all of the section in question is classified as a part of the Bridge Creek Member.

In most Kansas localities, three additional markers are recognized in the Hartland or in its Bridge Creek equivalent. These are bentonite seams and include 1) the first bentonite seam below HL-1, lying less than 2.5 feet below HL-1 from southeastern Mitchell County northeastward to Washington County, and between 3.6 and 7.8 feet below HL-1 between western Mitchell County and Rush County. Correlation of this bentonite seam is uncertain south of Rush County. 2) A bentonite seam lying approximately 2/3 to 3/4 the distance from HL-3 to the base of the Jetmore (JT-1), and lying 19.7 feet above the base of the Bridge Creek Member in Hamilton County. This bentonite seam can be traced throughout the State and is labeled HL-4 on Plate 1. 3) A bentonite seam 0.04 to 0.13 foot thick lying 0.0 to 0.19 foot below to base of the Jetmore. This seam is traceable throughout the Kansas outcrop and lies 23.8 feet above the base of the Bridge Creek Member in Hamilton County. These bentonites are not traceable on their field characteristics alone but must be identified according to stratigraphic position with respect to other marker beds, or, in the case of the last-mentioned seam, by its close association with the hard, brittle, chalky limestone bed that marks the base of the Jetmore Member in central Kansas.

Facies Changes in Hartland Member

Both lower and upper parts of the Hartland Member grade laterally, by gradual change of facies, into rocks assigned to other members of the Greenhorn. The Lincoln-Hartland contact descends stratigraphically in a southwestward direction from the northern part of central Kansas to Ford County as has been remarked above. The evidence may be summarized briefly, as follows: 1) In the area from Washington County to Hodgeman County the interval separating the top of the Lincoln from Hartland marker HL-1 increases irregularly from 2.5 feet at Locality 6 to at least 12.4 feet at Locality 11. 2) Still farther southwest, at Locality 8 (Ford County) this interval is 40 feet thick and consists mostly of shaly chalk of Hartland aspect, i.e., nearly free of skeletal limestone. However, within this 40-foot interval are approximately 13 feet of shaly chalk containing Lincoln-like lenses and a few thin beds of skeletal limestone. The top of the skeletal-limestone-bearing interval lies 12.7 feet below HL-1 and is regarded as the approximate lithostratigraphic equivalent of the top of the Lincoln in Rush (Locs. 15, 17) and Ellis (Loc. 5) counties. In Ford County the Lincoln would thus appear to be mostly older than farther to the northeast. This conclusion is borne out by biostratigraphic evidence. 3) To the west of Ford County the top of the Lincoln lies 44.4 feet below HL-1 and therefore lies nearly the same distance below that marker as in Ford County. Fossils in the upper part of the Lincoln in Ford and Kearny counties are species found in the lower part of the Lincoln farther to the northeast.

At Locality 6 in western Washington County, the Hartland contains only three chalky limestone beds, namely HL-1, HL-2, and HL-3. In addition, a single burrow-mottled shaly zone lies near the top of the Hartland, above HL-3. Southwestward from Locality 6 additional chalky limestone beds and zones of burrow-mottled chalk characterize a progressively thicker interval between HL-1 and the top of the member (see Pl. 1). Thus, at Locality 4 (Mitchell County) a burrow-mottled chalk bed is present between HL-2 and HL-3, and there are four burrow-mottled chalk beds between HL-3 and the top of the Hartland. At Locality 3 (Russell County) the HL-2 to HL-3 interval contains a burrow-mottled chalky limestone bed probably equivalent to the burrow-mottled chalk bed at Loc. 4 and, below this, a discontinuous layer of chalky limestone lenses. A 0.1-foot thick bed of burrowed chalk lies 0.7 foot below HL-3 at Locality 3. Above HL-3 the section contains six burrow-mottled chalk layers. At Locality 15, Rush County, the HL-2 to HL-3 interval contains the same burrow-mottled chalky limestone as at Locality 3 and also a burrow-mottled chalk layer 0.6 foot below HL-3, but the discontinuous chalky limestone bed of Locality 3 is missing. Above HL-3, the Hartland contains four, perhaps five, beds of burrow-mottled chalky limestone and three beds of burrow-mottled chalk, as well as three non-burrowed chalk beds. At Locality 9, Hodgeman County, the interval from HL-2 to HL-3 is not exposed, but above HL-3 are ten beds of chalky limestone, most of which are harder and thicker than chalk or chalky limestone beds in this interval farther to the north. Burrow mottling is evident in all of these beds either here or at a more weathered section that is exposed one mile to the northeast (Loc. 50). Although I have made no effort to trace regionally the individual chalky limestone beds above HL-3, it is apparent from the spacing and relationship to marker beds that some of those at Localities 9 and 50 represent beds that occur farther to the northeast. Because of the regionally widespread character of Hartland marker beds and nearly all limestone beds in, the Jetmore it is suggested that each of the Hartland burrowed chalk beds lying above HL-3 in the more northeasterly areas of central Kansas are represented by one of the chalky limestone beds at Localities 9 and 50. Thus, as one traverses the outcrop from northeast to southwest, in the Hartland interval above HL-3 the number of burrow-mottled beds is greater, individual beds are thicker, and lithology changes from chalk to chalky limestone. At Localities 9 and 50 the chalky limestones are not as hard or resistant to weathering as in the overlying Jetmore so that despite considerable resemblance to the Jetmore this part of the section was not included in that member by Moss (1932, p. 29). In western Kansas, at Locality 14 (Hamilton County) two hard burrow-mottled chalky limestone beds lie between HL-2 and HL-3, HL-3 is also harder than to the east and northeast, and several chalky limestones lying between HL-3 and the base of the Jetmore equivalent are hard and burrow mottled as in the Jetmore. At this locality the section between the base of HL-1 and the Fencepost limestone is more homogeneous than in central Kansas, consisting essentially of thin to medium beds of hard chalky limestone alternating with thicker units of shaly chalk. The entire interval was called Bridge Creek Limestone Member by Bass (1926, p. 67) and the term Bridge Creek has been widely adopted for this part of the Greenhorn section in Colorado. The term "Bridge Creek" is retained for this interval in the present report, although I can easily recognize in the member the exact equivalents of the middle to upper Hartland, the Jetmore, and the Pfeifer of central Kansas. There is no doubt whatsoever that the middle and upper parts of the central Kansas Hartland pass laterally into the lower part of the Bridge Creek Member, with the result that the Hartland-Bridge Creek contact of Hamilton County represents an older horizon than does the Hartland-Jetmore contact in central Kansas. In central Kansas the base of HL-1 lies as little as 0.9 foot above the base of the Hartland (Loc. 20). At Localities 13 and 14 (Kearny and Hamilton counties) the base of HL-1 is at the top of the Hartland. From these facts stems the conclusion that nearly all of the type Hartland is older than the Hartland of the northern part of central Kansas. This conclusion is supported fully by biostratigraphic data that are discussed in detail below.

Skeletal limestone

Thin to very thin, usually small lenses or very thin beds of hard skeletal limestone are distributed sparingly in the Hartland Member. In most central Kansas exposures a scattering of such limestone occurs in the lower few feet of the member testifying to the gradational change of depositional environment that led from the Lincoln to the Hartland kind of sedimentation. Sparse skeletal limestone occurs locally between Hartland marker beds HL-1 and HL-2 (Loc. 46), shortly above marker bed HL-2 (Locs. 3, 20, 24) and in the upper part of the Hartland (Locs. 20, 24). At no place in central Kansas does hard skeletal limestone comprise a characteristic feature of the member. At Locality 8 (Ford County) a portion of the Hartland that is judged to be equivalent to the middle and upper Lincoln of areas farther to the northeast contains numerous thin beds and lenses of skeletal limestone, but at Locality 13 (Kearny County) the same part of the section contains little rock of this kind. At Locality 14 (Hamilton County) the lower part of the Bridge Creek Member contains a little skeletal limestone above marker bed HL-3. At several localities thin laminae or lamina-like lenses of planktonic foraminiferal tests help to impart a laminated appearance to the section, especially in the upper part of the section (see Fig. 8,B).

Most of the Hartland skeletal limestones are of the kind I call inoceramite, i.e., composed largely of Inoceramus prisms and commonly containing larger pieces of broken Inoceramus valves. A few are composed principally of planktonic foraminiferal tests, chiefly Hedbergella, and there are gradational varieties comprising mixtures of these two components. These rocks are most commonly pale yellowish brown, weathering grayish orange, but a few are light olive gray (5Y5/2) or, rarely, yellowish brown (10YR5/2). Some of the lenses or very thin laminae of foraminiferal limestone occurring above marker bed HL-3 are light gray in color.

Skeletal limestones of the Hartland usually emit a petroliferous odor when freshly broken. The rocks are usually hard and brittle, owing to tight cementation by sparry calcite, and are resistant to erosion. The thicker lenses and beds project prominently from weathered slopes but rarely litter the surface with slabs as in the Lincoln Member.

Bentonite

Various exposures of the Hartland Member contain differing numbers of bentonite seams. In a section that contains so many widespread limestone and bentonite seams the fact that the number of bentonite seams differs from one area to another needs explanation. Possible reasons are: 1) the Hartland of Ford County (Loc. 8) and Kearny County (Loc. 13) embraces a part of the section that is largely older than the Hartland elsewhere in Kansas and therefore does not contain the same sequence of seams; 2) some bentonite seams are very thin (less than 0.01 foot thick) and are difficult to detect, especially in weathered sections; and 3) some bentonite seams, especially very thin ones, may be discontinuous. The minimum number of bentonite seams observed in any of the detailed measured sections is 6, at the northeastern end of the central Kansas outcrop (Locs. 4, 6, 20). Towards the southwest this number increases to 7 at Locality 1, 8 at Locality 3, 9 at Localities 5 and 15, and 10 at a composite section including Localities 9 and 11. The increase in number of bentonite seams parallels the southwestward increase in number of Hartland chalk and chalky limestone beds. At Locality 8, where the Hartland includes beds that are older than farther to the northeast, the member includes 21, or possibly 22, bentonite seams. In Kearny and Hamilton counties a composite section (Locs. 13 and 14) equivalent to the Hartland at Locality 8, and including the lower part of the Bridge Creek Member contains 20, or possibly 21, bentonite seams.

Hartland bentonite seams range in thickness from less than 0.01 foot to a maximum of 0.71 foot. The bentonite seam lying on marker bed HL-3 (Fig. 9,D) has the greatest average thickness, 0.45 foot for 19 measurements, and ranges from 0.25 foot at Locality 14, where it is included in the Bridge Creek Member, to 0.6 foot at Localities 1 and 4. The bentonite lying between marker beds HL-1 and HL-2 is the second most conspicuous, ranging from 0.12 foot (Locs. 6 and 20) to 0.71 foot (Loc. 15), averaging 0.31 foot for 16 measurements.

The bentonites are seen mostly in a deeply weathered state. The most common coloration is nearly white, very light gray, grayish orange and, overwhelmingly dominant, dark yellowish orange. The last two colors are believed due to limonite staining. A wide variety of other colors were recorded, mainly including several shades of grayish yellow, yellowish gray, and olive gray. Coloration of apparently unweathered bentonite is medium gray, light bluish gray, or medium olive gray but such rocks are rare. In many places the bentonite is noticeably gritty owing to small amounts of quartz silt that has been detected in X-rayed samples, and possibly to undevitrified glass. Biotite was observed in bentonite seams at several localities. The seam lying nearly at the top of the member is most consistent in containing minute flakes of a biotite-like mineral. Seams of granular selenite occur commonly above and/or beneath Hartland bentonite seams and small crystals of selenite are incorporated in the seams at a few places. Pyrite nodules, or limonite nodules altered from pyrite, were recorded in bentonite seams at a few localities but are rare compared with those found in bentonite seams of the Smoky Hill Member of the Niobrara Chalk. Not all Hartland bentonite seams are continuous. Seams that can be traced to a featheredge within a single exposure were noted at two localities and the differing number of seams noted at various places is owing at least in part to such discontinuities.

Several samples of Hartland bentonite were analyzed by X-ray diffraction techniques. These include two samples of the bentonite lying between marker beds HL-1 and HL-2, four samples of the bentonite lying on marker bed HL-3, one sample of the bentonite labeled HL-4 on Plate 1, and five samples from seams lying below HL-1, including three from the type Hartland. Of these samples 8 are composed dominantly of montmorillonite and 4 are composed dominantly of kaolinite. All of the kaolinite-rich samples are from Localities 13 and 14 in Kearny and Hamilton counties; however, two samples from these localities are dominated by montmorillonite. At Locality 3 the bentonite lying between HL-1 and HL-2 is nearly pure montmorillonite and contains a trace of quartz; at Locality 13 this same bentonite contains kaolinite. At both localities the adjacent rock can be described as unweathered. The bentonite lying on marker bed HL-3 is pure montmorillonite at Localities 3, 4, and 6, central Kansas, but is composed mostly of kaolinite at Locality 14 (Hamilton County). Locally this bentonite contains a little feldspar. Quartz is present mostly in trace quantities in half of the samples analyzed. Gypsum, a product of weathering, was recorded in two of the samples. Trace quantities of feldspar and/or mica (probably biotite) were recorded in a few of the X-rayed samples.

Macroinvertebrate Fossils

The biostratigraphic zonation of Hartland strata, treated in a later section of this report, is not based on all macroinvertebrate species in the member. The following list includes all forms recorded in the Hartland and equivalent Bridge Creek strata during the present study. Inclusion of a taxon in this list does not indicate co-occurrence with all of the other species. Common forms are preceded by an asterisk. Rare forms, or those known from only one locality, are preceded by a dagger.

| Brachiopods: | |

| †Discinisca sp. | |

| Gastropods: | |

| *Cerithiella sp. A (undescribed) | |

| Bivalves: | |

| Inoceramus flavus Sornay | |

| *Inoceramus (Mytiloides) labiatus (Schlotheim) | |

| *Inoceramus prefragilis Stephenson | |

| Inoceramus cf. I. tenuistriatus Nagao & Matsumoto | |

| †Martesia? sp. | |

| †Plicatula? sp. | |

| Phelopteria sp. A (undescribed) | |

| Syncyclonema? sp. | |

| †Teredolithus sp. | |

| Cephalopods: | |

| Allocrioceras annulatum (Shumard) | |

| *ammonite molds, unidentified fragments | |

| *Baculites sp. (smooth) | |

| †Calycoceras cf. naviculare (Mantell) | |

| †Calycoceras? sp. | |

| Desmoceras (s.l.) sp. | |

| Eucalycoceras sp. B | |

| Hemiptychoceras reesidei Cobban & Scott | |

| *Kanabiceras septemseriatum (Cragin) | |

| Metoicoceras whitei Hyatt | |

| †Pseudocalycoceras dentonense (Moreman) | |

| †Puebloites sp. | |

| †Scaphites brittonensis Moreman | |

| Sciponoceras gracile (Shumard) | |

| †Stomohamites? sp. | |

| †Tragodesmoceras bassi Morrow | |

| *Watinoceras reesidei Warren | |

| *Worthoceras vermiculum (Shumard) | |

| Worthoceras gibbosum Moreman | |

| Cirripeds: | |

| acrothoracian barnacle borings | |

Hartland macroinvertebrate fossils are illustrated in Plates 5 and 6.

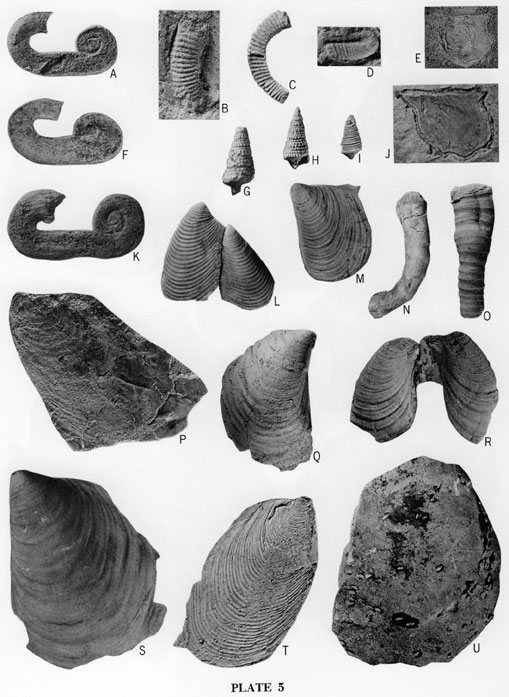

Explanation of Plate 5

Mollusks from the Hartland Member

A,F,K, Worthoceras vermiculum (Shumard): A,F, crushed internal molds, both X2, KU82116, KU82115, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 11; K, internal mold, X2, specimen collected by W. A. Cobban, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 3.

B,C, Allocrioceras annulatum Shumard: internal mold fragments, B is X2, C is X1, KU82125, KU82124, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 6.

D, Hemiptychoceras reesidei Cobban & Scott: latex cast of internal mold, X2, KU82123, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 2.

E,J, Phelopteria sp. A: E, flattened left valve, X1, KU82138, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 5; J, interior view of right valve, X1, KU82137, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 3.

G,H,I, Cerithiella sp. A: G, calcite replica, X2, KU82140, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 66; H, recrystallized shell, X2, KU82141, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 11; I, recrystallized shell, X1, KU82139, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 35.

L,M, Inoceramus prefragilis Stephenson: L, internal molds of two left valves, X1, KU82129, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 35; M, internal mold of left valve, X1, KU82128, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 3.

N,O, Martesia? sp.: calcareous tubes, both X1, KU82135, KU82136, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 35.

P, Mytiloides labiatus (Schlotheim): partially preserved, flattened right valve, internal aspect, X1, KU82131, lower part of Bridge Creek member equivalent to upper part of Hartland Member of central Kansas, Locality 14.

Q,R, Inoceramus flavus Somay: Q, latex cast of interior of right valve, X1, KU82190, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 3; R, paired internal molds of deformed specimen (possibly I. prefragilis Stephenson), X1, KU82130, middle part of Hartland Member at Locality 13.

S, Inoceramus cf. I. tenuistriatus Nagao & Matsumoto: internal mold of left valve, X1, KU82133, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 4.

T, Inoceramus sp.: Flattened internal mold of right valve, X1, KU82132, upper part of Hartland Member at Locality 9.

U, Acrothoracian barnacle boring impressions on internal mold of Inoceramus, X1, KU82134, lower part of Hartland Member at Locality 5.

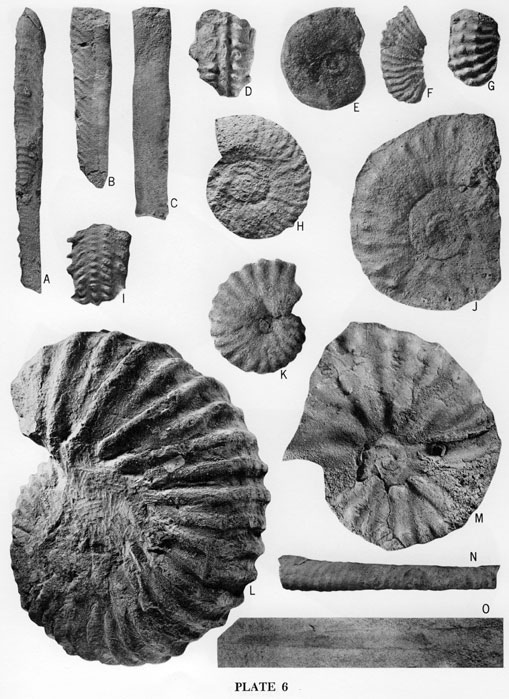

Explanation of Plate 6

Ammonites from the Hartland Member

A,B,N, Sciponoceras gracile (Shumard): A, latex cast of external mold, X1, KU82109, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 24; B, fragment of internal mold, X1, KU82110, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 26; N, internal mold, X1/2, KU82108, float from marker bed HL-2 at Locality 3.

C,O, Baculites sp.: C, internal mold fragment, X1, KU82111,

marker bed HL-2 at Locality 26: O, flattened mold, X1, KU82112, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 11.

D,I, Kanabiceras septemseriatum (Cragin): internal mold fragments, ventral aspect, both X1, KU82119, KU82120, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 3.

E, Desmoceras (s.l.) sp.: internal mold, X1, KU82121, middle part of Hartland Member at Locality 13.

F,G, Pseudocalycoceras dentonense (Moreman): F, fragment of internal mold, X1, KU82114, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 11; G, latex cast of external mold fragment, X1, KU82113, marker bed HL-2 at Locality 11.

H, Tragodesmoceras bassi Morrow, internal mold, X1, KU82127, upper part of Hartland Member at Locality 51.