Prev Page--Contents || Next Page--Geology

Introduction

Purpose and Scope

Irrigation by wells in Walnut Creek valley in Rush County during the dry 1950's demonstrated the economic importance of the ground-water resource. Because water supplies in the county are obtained principally from wells, ground water must be utilized in the best possible manner to ensure availability of this most important natural resource for future use.

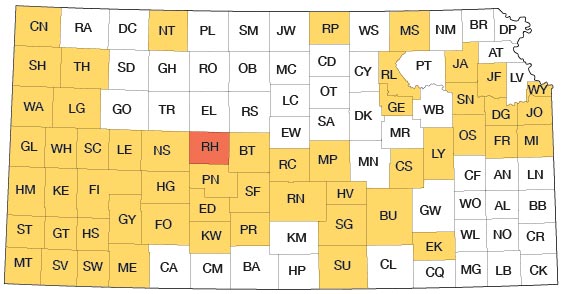

This investigation was begun in August 1959 to determine the occurrence, availability, chemical characteristics, and geologic controls of ground water in Rush County. The study is part of a continuing program of geology and ground-water-resources investigations that was begun in Kansas in 1937 by the U.S. Geological Survey and the State Geological Survey of Kansas, in cooperation with the Division of Sanitation of the Kansas State Board of Health (now the Division of Environmental Health of the Kansas State Department of Health) and the Division of Water Resources of the Kansas State Board of Agriculture. The present status of the program is shown on figure 1.

Figure 1--Index map of Kansas showing area described in this report and areas covered by other online geologic reports, as of Aug. 2008. For additional information, please visit the KGS Geologic Maps of Kansas Page.

Location and Extent of Area

Rush County, in central Kansas, is in the fourth tier of counties south of the Kansas-Nebraska border and is the sixth county east of the Kansas-Colorado border (fig. 1). The bordering counties are Ellis on the north, Barton on the east, Pawnee on the south, and Ness on the west. The county contains 20 townships from T. 16 S. to T. 19 S. and from R. 16 W. to R. 20 W., and has an area of 724 square miles.

Previous Investigations

Rush County and the surrounding area have been investigated and studied previously by several workers. Reports by these investigators are listed in the Selected References.

Methods of Investigation

Field work for this report was done in the fall of 1959, the summer of 1960, and a short time in the spring of 1961. Data collected at 222 wells included depth of the well and depth to water in the well, if measurable. Other pertinent data available were obtained from well owners. A total of 161 test holes were drilled in the county by the U.S. Geological Survey and the State Geological Survey of Kansas. The test holes were drilled with a hydraulic rotary drilling machine (24 holes) and with a pickup-mounted power auger (137 holes). Drill cuttings were collected and examined. Water-well drillers in the area furnished test-hole logs. Several hundred oil-well logs on file at the State Geological Survey of Kansas were studied. In addition, a few thousand shot-hole logs from several oil and seismic survey companies were obtained and examined.

Wells and test holes were located by aerial photographs and automobile odometer readings. The altitudes of inventoried wells and Survey-drilled test holes were determined by plane table and alidade.

Samples of water were collected by the author and analyzed in the laboratory of the Division of Environmental Health of the Kansas State Department of Health. Chemical analyses of water from some of the municipal wells also were obtained from the Department of Health.

Water levels in available irrigation wells have been measured annually at least six times since 1960. Monthly or quarterly measurements are continuing on eight observation wells at the present time (1973).

Geology was mapped on aerial photographs obtained from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and transferred to a base map compiled from maps of the U.S. Soil Conservation Service and State Highway Commission of Kansas.

Well-Numbering System

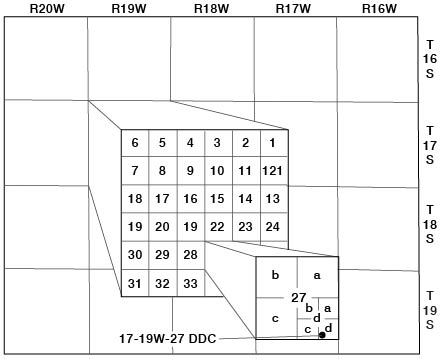

Well and test-hole numbers in this report describe the location of wells and test holes according to General Land Office survey procedure as follows: first number, township; second number, range; third number, section; first letter, 160-acre tract (quarter section) within that section; second letter, 40-acre tract (quarter-quarter section) within that quarter section; third letter, 10-acre tract ( quarter-quarter-quarter section) within that quarter-quarter section. The 160-acre, 40-acre, and 10-acre tracts are designated a, b, c, and d in a counterclockwise direction beginning in the northeast corner. For example, well 17-19W-27ddc is in the SW SE SE sec. 27, T. 17 S., R. 19 W. (fig. 2). When two or more wells are located in the same 10-acre tract, the wells are numbered serially in the order they were inventoried.

Figure 2--Well-numbering system used in this report.

Acknowledgments

Thanks and appreciation are expressed to the many county residents who permitted access to their property and supplied information on their wells, to the municipal officials who provided information on city water supplies, to well drillers who supplied well and test-hole logs, and to oil and service companies that provided shot-hole logs. Special acknowledgment is made to the owners of the irrigation wells that were used in aquifer tests, and to Mr. Jerry Oborny for the copy of water-level measurements of several years duration for his irrigation well.

Topography and Drainage

Most of Rush County is in the Smoky Hills section of the Great Plains physiographic province (Frye and Schoewe, 1953). The southeast corner of the county is in the Great Bend Region, and the northwest corner is in the High Plains.

The altitude of land surface in Rush County ranges from slightly more than 2,300 feet above mean sea level in the northwest and southwest corners of the county to slightly less than 1,850 feet in the northeast corner. The maximum relief is somewhat more than 450 feet, but local relief seldom exceeds 100 feet.

Approximately the north third of Rush County is in Smoky Hill River drainage basin, but the Smoky Hill River occurs in Rush County only in secs. 5 and 6, T. 16 S., R. 17 W. Big Timber Creek is the largest tributary to the Smoky Hill River in Rush County; it heads in northeastern Ness County, enters Rush County in the vicinity of McCracken, and enters Ellis County northeast of Liebenthal. Other Smoky Hill tributaries in Rush County include Shelter Creek, Duck Creek, and Eagle Creek.

The south two-thirds of Rush County is in Arkansas River drainage basin. The major stream in this part of the county is Walnut Creek, which heads in western Lane County about 55 miles west of where it enters Rush County near Alexander. Walnut Creek flows eastward across Rush County and enters Barton County east of Shaffer. Major tributaries to Walnut Creek from the south include Old Maid Fork, Sandy Creek, and Otter Creek. Alexander Dry Creek and Sand Creek are the major tributaries to Walnut Creek from the north. Dry Walnut and Dry Creeks trend east-northeast in the southeast quarter of Rush County and enter Walnut Creek in Barton County. Along the south side of Rush County are headwater areas for some tributaries of Pawnee River.

Walnut Creek is an underfit stream; that is, it appears to be too small to have eroded the valley in which it flows. Walnut Creek valley ranges from about 1 to 3 miles in width across Rush County. Prior to the development of extensive irrigation from wells in the valley-fill deposits, Walnut Creek was a perennial stream through Rush County except after long droughts.

Climate

The climate of Rush County is characterized by abundant sunshine, moderate precipitation, high rates of evaporation, moderate to high wind velocities, and frequent and abrupt weather changes. Hot days and cool nights are typical in summer. During winter, temperatures are moderate to cold with occasional short periods of severe cold. Thundershowers are prevalent in spring and summer, and blizzards occur in winter.

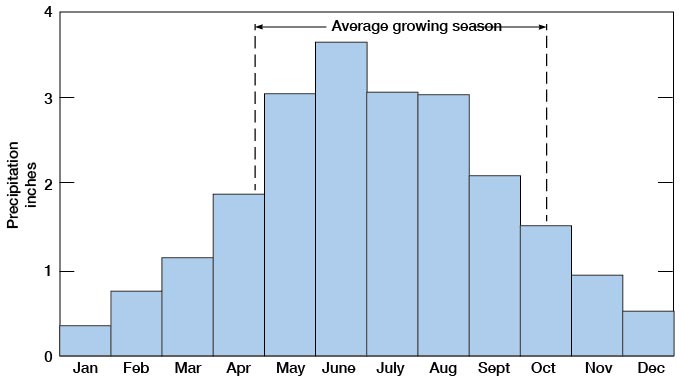

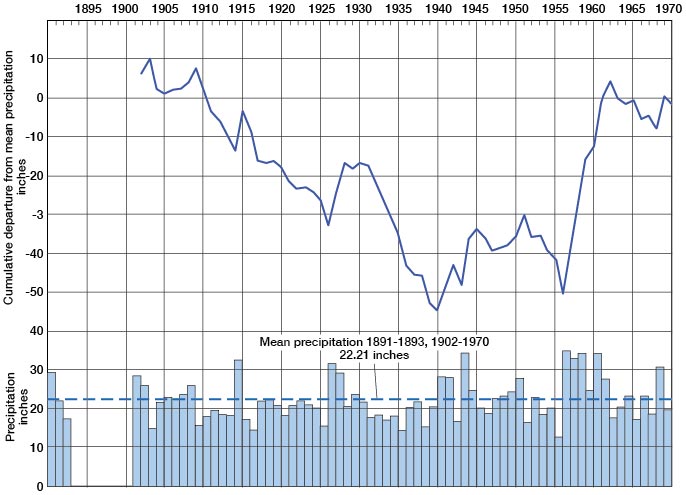

The first precipitation records of the National Weather Service (formerly U.S. Weather Bureau) for Rush County date from 1891 to 1893. Precipitation records resume in 1902 and, with temperature records, continue to the present. The weather station was at La Crosse until 1923, when it was moved to Bison.Three additional gages were installed at Alexander, Loretta, and McCracken in late 1940. Mean monthly precipitation through 1970 at Bison is shown on figure 3. Figure 4 shows the annual precipitation, the mean annual precipitation, and the cumulative departure from mean annual precipitation for the period of record at Bison (includes early record at La Crosse). Recorded annual precipitation in Rush County has ranged from 37.37 inches at Alexander in 1944 to 10.76 inches at Alexander in 1956.

Figure 3--Mean monthly precipitation 1891-93, 1902-70 and average growing season at Bison.

Figure 4--Annual precipitation and cumulative departure from mean precipitation at Bison.

Approximately three-quarters of the precipitation in Rush County occurs from April through September, which coincides with the growing season. The growing season at Bison has ranged from 140 to 207 days and averages 174 days.

The latest recorded date of a killing frost in the spring is May 27, 1907, and the average date is April 25. The earliest recorded date of a killing frost in the fall is September 17, 1903, and the average date is October 16. Recorded temperatures in Rush County have ranged from 116°F on July 13, 1934, to -25°F on January 12, 1912.

Population

The first settler in Rush County arrived in 1870 and the first family in 1871. Rush County was organized in 1874, and in 1875 counted 451 residents. In 1970 the county had a population of 5,117 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1971), of which 3,246 or 63.4 percent lived in incorporated cities and 1,871 or 36.6 percent lived on farms or in unincorporated communities [Note: Rush County population was listed as 3,551 in 2000 U.S. census (KU Institute for Policy & Social Research).]. The population decreased 16.9 percent between 1960 and 1970. La Crosse, the largest city and the county seat, bad a population of 1,583 in 1970 [1,376 in 2000]. Other communities and their 1970 population were: McCracken, 333 [211 in 2000]; Otis, 387 [325 in 2000]; Bison, 285 [235 in 2000]; Rush Center, 237 [176 in 2000]; Liebenthal, 169 [111 in 2000]; Alexander, 129 [75 in 2000]; and Timken, 123 [83 in 2000]. The average density of population in Rush County in 1970 was 7.1 per square mile as compared with 27.5 for the entire State [density of 3.9 in 2000, with state value of 32.9].

Agriculture

Agriculture is the dominant economic activity in Rush County. Crops valued at $6,996,960 and poultry and livestock valued at $5,017,220 were produced in Rush County in 1970 (Kansas State Board of Agriculture, 1971). The acreage and value of principal crops harvested in the county in 1970 are given in table 1.

Table 1--Acreage and value of principal crops harvested in 1970 (Kansas State Board of Agriculture, 1971 ).

| Crop | Acres | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Wheat | 143,000 | $5,300,000 |

| Sorghum, all purposes | 24,800 | 962,300 |

| Corn, all purposes | 2,900 | 333,100 |

| Oats | 280 | 6,300 |

| Barley | 360 | 8,900 |

| Hay, all purposes | 7,300 | 370,800 |

| Other crops | 210 | 15,560 |

| Total | 178,850 | $6,996,960 |

Mineral Resources

The mineral resources of Rush County include oil and gas, helium, sand and gravel, "quartzite," and limestone, in addition to ground water. The U.S. Bureau of Mines (1971) lists petroleum products, helium, and sand and gravel, having a value of $6,749,354, as minerals produced commercially in Rush County in 1969.

Oil and Gas

The first recorded drilling for petroleum products in Rush County was in 1903 when a dry hole in the southeast corner of sec. 33, T. 17 S., R. 17 W., reached a depth of 2,004 feet and another dry hole in the southwest corner of NW sec. 34, T. 17 S., R. 17 W., reached 2,095 feet (Landes and Keroher, 1938). A third unsuccessful attempt was made in 1924 in the SW sec. 3, T. 16 S., R. 16 W. In November 1928 the Danciger Oil and Refining Co. completed a gas well having a flow potential of 13 million cubic feet in the center of the NW sec. 27, T. 17 S., R. 17 W., which was the beginning of successful petroleum operations in Rush County. The first oil well was completed on September 21 1931, in the SW sec. 17, T. 19 S., R. 16 W.

The most important producing field, the Otis-Albert gas and oil field, dates from March 1930 when the discovery gas well in sec. 11, T. 18 S., R. 16 W., was completed. The first oil in the field was discovered in 1934. Other important fields are the Ryan, discovered in 1945, the Rush Center, discovered in 1947, the Reichel, principally gas, discovered in 1953, and the Webs, discovered in 1954. Cumulative oil production in Rush County was 15,759,679 barrels through 1970. In addition to natural gas, helium gas has been extracted by a plant at Otis from 1943 to 1945 and from 1951 to the present time. The cumulative production, the number of wells, the producing zones, and other statistical data for all fields in the county are presented in annual reports by the Mineral Resources Section of the State Geological Survey of Kansas. [For current information on oil and gas production, see the Survey's oil and gas page for Rush County.]

Sand and Gravel

Deposits of sand and gravel are not extensive in Rush County. Remnants of Ogallala Formation provide sand and gravel in T. 17 S., R. 19 W., and in T. 19 S., Rs. 17-20 W. Pleistocene deposits in T. 16 S., Rs. 16-18 W., have been used for road gravel, and a deposit of sand and gravel in sec. 3, T. 18 S., R. 20 W., was the source of part of the material used to build the asphalt-surfaced road between Alexander and McCracken. Small deposits of sand and gravel are present along stream courses within the county.

"Quartzite"

A silicified deposit of Ogallala crops out in the SW sec. 6 and the NW sec. 7, T. 16 S., R. 20 W., and extends westward into Ness County. The quantity of material in the Rush County deposits is not large, but the material could have local use as aggregate or building stone.

Limestone

The Fence-post limestone bed at the top of the Pfeifer Shale Member of the Greenhorn Limestone has been quarried extensively along the line of outcrop. No quarries are presently operating but reserves are very large. The limestone was and is used for fenceposts, as the name implies, over a wide area of central and north-central Kansas. In addition to fenceposts, the limestone has been used for foundations and buildings. The Catholic Church at Liebenthal is a fine example. The stone may be crushed and used as aggregate and for road material. Other limestone beds in the Greenhorn Limestone, and in the lowest part of the Carlile Shale, also have been quarried.

Prev Page--Contents || Next Page--Geology

Kansas Geological Survey, Geology

Placed on web Aug. 22, 2008; originally published July 1973.

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

The URL for this page is http://www.kgs.ku.edu/General/Geology/Rush/02_intro.html