| Kansas Geological Survey | Winter 2002 |

Vol. 8.1 |

|

Ogallala Aquifer

CONTENTS Ogallala Aquifer–page 1 Earth Science Teacher Honored–page 4

|

Declining

water levels in the Ogallala aquifer have gotten increasing attention

lately. Although most Kansans agree that something must be done to preserve

the Ogallala, the main water source for much of western Kansas, any plan

to conserve this crucial resource must take into account complex issues

and divergent viewpoints. Reaction to Governor Bill Graves' 2001 State of the State proposal, that

we stop depleting the state's aquifers by the year 2020, highlights the

range of opinion. While many said the 2020 goal for zero depletion—to

take no more water from the aquifer than is replenished by rainfall and

streamflow—would destroy the western Kansas economy, others argued

the goal wasn’t enough to preserve the aquifer for future generations.

About the only thing that no one disputes is that the Ogallala contains

a finite amount of water. The Ogallala is part of a larger aquifer system,

the High Plains aquifer, that extends under eight states in the Great

Plains. Measurements of ground-water levels in Kansas indicate that much

of the Ogallala has declined since the onset of large-scale irrigation

in the 1950's and 1960's. Based on past usage trends, researchers at the Kansas Geological Survey

made projections about the aquifer's usable lifetime, which varies considerably

from place to place. Although many parts of the aquifer should be able

to support pumping for 100 years or more, some parts are already effectively

exhausted: they've dropped below 30 feet of saturated thickness, the minimum

amount considered necessary to support large-scale pumping. Other parts

will be exhausted in the next 25 years. Despite the complex nature of both the problem and potential solutions,

some progress has been made towards developing a plan to conserve the

aquifer's remaining water. Two advisory committees appointed by the Kansas

Water Office developed recommendations that were finalized in a report

released in the fall of 2001. The committees, a management and a technical

advisory committee, were made up largely of people from western Kansas

and included staff from the KGS, Kansas Water Office, Division of Water

Resources (Kansas Department of Agriculture), Kansas State University,

Kansas Department of Commerce and Housing, U.S. Geological Survey, and

local Groundwater Management Districts (GMDs). "The report is a classic exercise in public decision making on a

complicated and fundamentally important issue," said technical advisory

committee member Wayne Bossert, manager of the Northwest Kansas GMD. "Somehow

we’ve got to get all the issues out there, and let the majority

of Kansans make a decision. This report is a pretty good effort at that." Chief among the report's recommendations was a proposal to divide the

aquifer into subunits. These aquifer subunits would be managed differently

based on their different characteristics—the saturated thickness

of the subsurface sediments, how easily they transmit water, and the rate

at which they are replenished by precipitation and streamflow. The three

western Kansas GMDs, locally managed political subdivisions, would be

responsible for delineating the subunits within their districts. To help the GMDs in this task, KGS water researchers are compiling and

evaluating a range of data, including best estimates of aquifer recharge,

ground-water levels, water usage, and climate trends for different parts

of the aquifer. The report also recommended using incentive-based programs (such as federal funds to buy and retire water rights) and improvements in technology and education to promote conservation and help extend the life of the aquifer. An educational resource center, the Ogallala Aquifer Institute, would further the educational part of these recommendations. The Institute is located at the Finnup Center for Conservation Education in Garden City, Kansas, and will provide education support activities for schools as well as adult education opportunities.

The Kansas Water Authority approved these recommendations for inclusion in the draft 2004 State Water Plan, the blueprint for managing the state’s water resources. The recommendations will be discussed during the March meetings of the 12 Basin Advisory Committees.

|

|

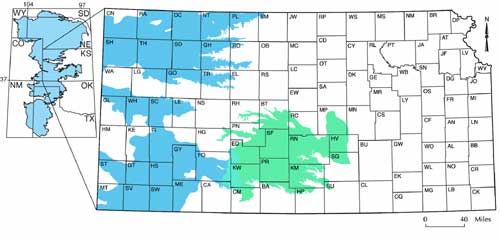

Extent of the Ogallala aquifer (shaded blue) within

the High Plains aquifer in Kansas. The Ogallala does not include the portion

of the High Plains aquifer in south-central Kansas (shaded green). |

|

| Next Page | Online February 10, 2003 Comments to: lbrosius@kgs.ku.edu Kansas Geological Survey URL:http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/GeoRecord/2002/vol8.1/Page1.html |