Kansas Geological Survey, Bulletin 41, pt. 8, originally published in 1942

Originally published in 1942 as Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin 41, part 8. This is, in general, the original text as published. The information has not been updated.

The rocks exposed at the surface in Phillips County, north-central Kansas, consist of the Ogallala formation of Pliocene age, and the Pierre shale, Niobrara limestone, and Carlile shale of Cretaceous age. The known mineral resources of the county include oil, stone, sand and gravel, ground water, bentonite, volcanic ash, and an ever-present fertile soil. A brief discussion of the subsurface beds ranging in age from Precambrian to Cretaceous, and a description of the oil-producing areas are included.

Research by the Kansas Geological Survey has led to the conclusion that the mineral resources of the state are much greater than heretofore realized. Our already established mineral industries contribute between 100 and 150 million dollars worth of new wealth every year. In addition, there are untapped resources of great value; the Kansas Geological Survey is engaged in investigating these, anticipating that their exploitation will follow.

The known mineral resources of Phillips County include oil, stone, sand and gravel, ground water, bentonite, and volcanic ash. The discovery of oil was made after this investigation of the mineral resources of Phillips County had begun. No doubt more oil and gas remain to be found. The stone, sand and gravel, and ground water are but partially developed. At the present time there is no exploitation of the large bentonite and volcanic ash deposits mapped by the Kansas Geological Survey in Phillips County.

It is the purpose of this paper to present factual data concerning the geology and mineral resources of Phillips County. By making this information available to the public, it is hoped that the development of the mineral industries will be expedited in this part of the state.

Several weeks were spent in Phillips County by the senior writer, during the summers of 1938 and 1939, studying the surface geology and surveying the mineral resources. Walker Josselyn assisted in the field during the latter part of the investigation. Norman Plummer, assisted by John Romary, visited the county and mapped and sampled several of the bentonite exposures. E. D. Kinney, in 1941, made additional investigations of the bentonite and its utilization. Through the help of Roy McDowell, County Engineer, an allotment of National Youth Administration funds was secured, and a crew trenched and hand-drilled one of the most promising of the bentonite exposures. Mr. McDowell also supplied considerable information concerning the boundaries of the bentonite, ground-water supplies, sand and gravel deposits, and stone quarries. The writers and the Kansas Geological Survey are very grateful to him for this valuable cooperation.

Raymond P. Keroher has prepared the parts of this article dealing with subsurface geology and with oil and gas development. In his studies of the subsurface geology of Phillips County, he was assisted by Glen Gordon. Data concerning the regional structure of Phillips County and the ground-water supplies were generously furnished by the Carter Oil Company, through Phil K. Cockran and Ben H. Richards, geologists. S. W. Lohman and J. C. Frye have contributed to and have reviewed the section on ground water. K. K. Landes is the author of other parts of the report and has generally guided the entire investigation.

To the people named, and to the many interested citizens of Phillips County who aided in the progress of the investigation, grateful thanks are given.

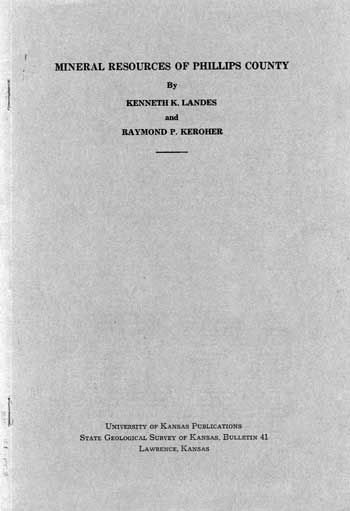

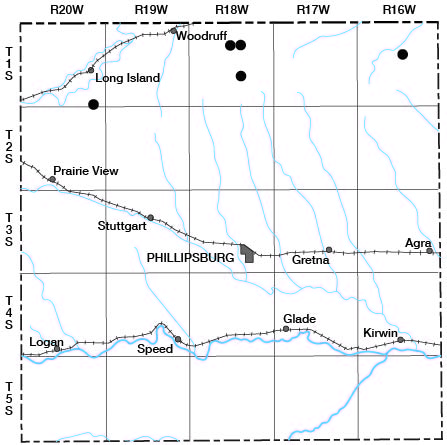

Phillips County lies in northwestern Kansas, immediately south of the Nebraska line, and between 99° and 100° meridians. Its location with respect to the other counties is shown on the accompanying map (Fig. 1). The population in 1940 (U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Census) was 10,435 [6,001 in 2000; Kansas Statistical Abstract 2009, KU Institute for Policy & Social Research, September 2010]. The largest city is the county seat, Phillipsburg, which lies almost in the center of the county. The population of Phillipsburg is listed as 2,109 [2,668 in 2000]. Other cities of the third class in Phillips County, with their populations, are Agra (406) [306 in 2000], Kirwin (392) [229 in 2000], Logan (703) [603 in 2000], Long Island (257) [155 in 2000], Prairie View (205) [141 in 2000], and Speed (111) [44 in 2000]. Unincorporated communities include Woodruff, Stuttgart, and Gretna.

Figure 1--Map of Kansas showing location of Phillips County. [Other reports placed online are also indicated, as on Aug. 2011]

Each of the towns and communities lies along one of three railroad lines that serve the county. The Lenora branch of the Missouri Pacific crosses the county from west to east, 6 to 8 miles north of the Rooks County line. It passes through Logan, Speed, Glade, and Kirwin. State Highway 9 parallels this railroad and passes through the same towns. The main line of the Rock Island crosses central Phillips County from west to east. Prairie View, Stuttgart, Phillipsburg, Gretna, and Agra are served by this railroad. U.S. Highway 36 runs parallel to the railroad but passes a short distance to the south of all these communities except Phillipsburg. Long Island and Woodruff lie on both the Oberlin branch of the Burlington railroad and on U.S. Highway 83. Both of these lines of communication cut across the northwest corner of the county. One state highway, Kansas Highway 1, crosses Phillips County from south to north, passing through Glade and Phillipsburg. The county is also crossed by three north-south and three east-west county roads. Both of the U.S. highways and K-1 are paved with asphalt. K-9 and some sections of the county roads are graveled. Access is easy to all parts of the county at almost any time of year.

The principal industry is farming and both wheat and row crops are raised. Phillipsburg is a division point on the Rock Island. A refinery was recently erected here to handle crude oil produced by the several fields to the south which lack pipeline outlets.

Phillips County lies in the Plains Border section of the Great Plains physiographic province, but in this part of the state the plains are highly dissected. The major streams and their many tributaries have eroded the surface to such an extent that the Tertiary Ogallala formation, the "caprock" of the High Plains, has been completely removed over the central and southeastern sections of the county, exposing the underlying chalk and chalky shale of the Niobrara formation. This rock is easily eroded; running water has carved it into patches of "badlands" at many places. Even where the Ogallala yet remains at the surface, as in the northwestern third of the county, it has been eroded into valleys and ravines that are separated by narrow divides. Consequently, almost the entire surface is rough, without, however, any great magnitude to the relief.

Phillips County is drained by two tributaries of Kansas River: the Republican, which flows eastward a short distance north of Phillips County in Nebraska, and the North Fork of Solomon River, which flows east across southern Phillips County. The divide between the two drainage systems lies in the north tier of townships, except on the western side of the county where it moves south into the second tier.

Only one tributary of the Republican River in Phillips County is a permanent stream. This is Prairie Dog Creek, which flows northeast across the northwest corner of the county. To the east, along the north tier of townships, are several northward-flowing intermittent streams which drain into the Republican.

The principal tributaries of the North Fork of Solomon River are Deer and Bow creeks, both of which join the Solomon near Kirwin. Deer Creek heads between Stuttgart and Prairie View and flows southeastward, passing by Phillipsburg about one-half mile southwest of the southwest corner of the townsite. Central Phillips County is drained by southward-flowing intermittent tributaries of this stream. Bow Creek runs across southwestern Phillips County and northwestern Rooks County, crossing and recrossing the county line several times before heading northeast into the Solomon.

The highest point in the county is along the divide between the Solomon and Republican River watersheds at about the middle of the south side of sec. 11, T. 2 S., R. 20 W. The elevation here is approximately 2,350 feet. The lowest point is where the North Branch of Solomon River leaves the county. The elevation of this point is about 1,670 feet, making a maximum relief for Phillips County of 680 feet.

The uplands in the northern half of Phillips County and south of Solomon River are strongly dissected, due to erosion by intermittent streams. The same condition exists in western Phillips County between Deer Creek and Solomon River. A relief of 200 feet in a mile is not unusual in these areas.

Because there are no upland flats of any great magnitude, the only extensive flat areas in Phillips County are the floodplains of the major streams. The Solomon River plain is from one to one and one-half miles wide. The towns of Logan, Speed, Glade, and Kirwin lie along it, and it is followed by the Missouri Pacific railroad and highway K-9. The Burlington right-of-way and U.S. highway 83 lie, for the most part, on the floodplain in Prairie Dog Creek. This plain is exceptionally wide in the vicinity of Long Island, exceeding 1 1/2 miles.

Practically all of Phillips County is floored by chalk and chalky shale belonging to the Niobrara formation of Late Cretaceous age. The next younger formation, the Pierre shale, is exposed in a few places in the northwest corner of the county in the valley of Prairie Dog Creek. Although not shown on the state geologic map, the Carlile shale, which underlies the Niobrara formation, is exposed in the southeastern part of the county, owing mainly to the presence of the Stockton anticline. The Ogallala formation of Tertiary age at one time covered the entire county, and large areas are still veneered with remnants of this formation. The uplands north of the north fork of Solomon River in the northwestern and northern parts of Phillips County are covered with Tertiary sediments. A smaller tongue of Ogallala lies in the southwestern part of the county between the north fork of the Solomon River and Bow Creek. A thin blanket of the even younger loess covers much of the county. Recent deposits, mainly sands and gravels, are confined chiefly to the river bottoms.

Sediments deposited during the Quaternary period are all of continental type. The youngest of these sediments are the sands and gravels composing the floodplains of the major streams and their tributaries. Before the dissection of the present topography, windborne loess was deposited over northern and western Kansas at about the same time that the Pleistocene volcanic ash deposits of central and western Kansas were formed (Landes, 1928; Smith, 1940; Frye and Hibbard, 1941). Phillips County contains one large Pleistocene ash deposit and several small ones. The large one lies in sec. 33, T. 5 S., R. 19 W. Further description of this deposit is found in the section on volcanic ash in this bulletin.

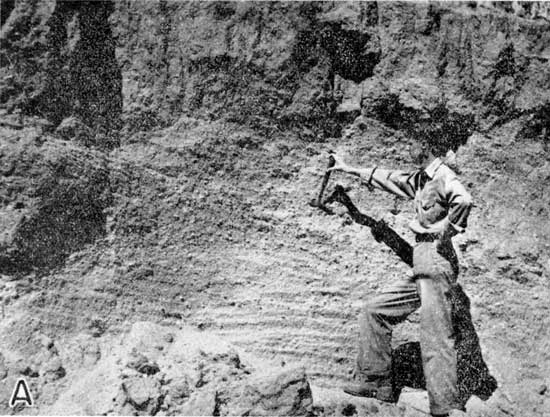

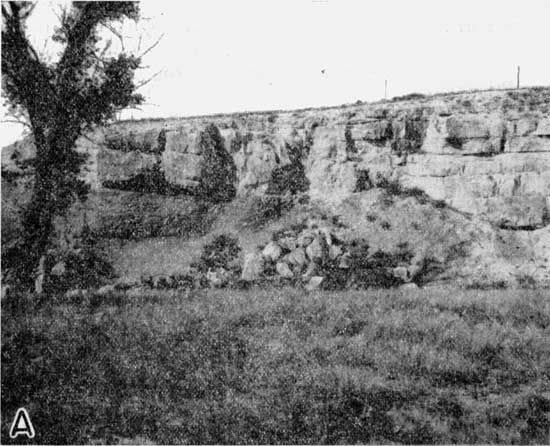

Next older are the high terrace gravels which are remnants of an older and higher drainage pattern (pl. 1A). Examples are to be found in the SE corner NE sec. 1, T. 1 S., R. 20 W., and in NW sec. 33, T. 4 S., R. 19 W. At both of these localities the sand and gravel have been quarried for commercial purposes and detailed descriptions will be found in the section on sand and gravel. The sand grains consist mostly of quartz that obviously were derived either from older Ogallala formations or from the crystalline rocks of the Front Range of the Rockies. Coarser material includes both granite fragments, which have had the same origin as the quartz grains, and fragments of chalk, some of which are silicified and which may measure as much as 6 inches across. The chalk came from local Niobrara beds.

Plate 1A--Gravel deposit in NE corner sec. 26, T. 2 S., R. 20 W.

The Ogallala formation, of Tertiary age, covers the uplands north and south of the north fork of Solomon River. Its maximum thickness probably does not exceed 50 feet, and this thickness is confined to the highest divides. Elsewhere, the Ogallala has been partly or completely removed by erosion. The formation consists of sands, silts, and some zones of coarser material. The so-called "mortar beds," which are grit layers cemented with calcium carbonate, are abundant in the areas of Ogallala exposures. The calcium carbonate in some of the mortar beds has been replaced by silica so that a quartzite or quartzitic conglomerate is formed (pl. 4A). Ferrous iron that is present in the silica gives the entire rock a green color. Some of the mortar beds contain pebbles of chalk, which are not completely silicified; and, upon exposure, this rock becomes pitted. The commercial utilization of the Ogallala is discussed in the section on stone.

All of the pre-Ogallala formations exposed in Phillips County belong to the Cretaceous System. All were deposited in marine waters that were parts of great seaways covering most of the Cordilleran and Great Plains areas.

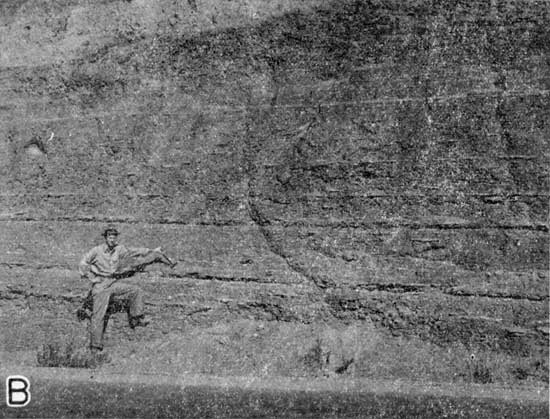

The youngest Cretaceous formation in Phillips County is the Pierre shale, and only the lowermost few feet of this formation occurs here. Exposures of this formation are very poor in Phillips County, but a good section is available a short distance north of the county in a roadcut on U.S. Highway 83 in Harlan County, Nebraska (pl. 1B). Here, the Pierre consists of a hard gray shale with gypsum streaks and zones of gypsum nodules. The shale breaks into small hard flakes. It contains, in addition to gypsum, a few thin hard layers of yellow bentonite and a few equally thin beds of limonite, having a sulfur yellow color. Calcium carbonate is present in this part of the Pierre, but is decidedly subordinate.

Plate 1B--Highway cut in Pierre shale between Phillips County and Republican River.

Other, but much smaller, exposures of Pierre shale were found in the valley of Prairie Dog Creek, especially in NE sec. 35, T. 1 S., R. 20 W., in the SW corner sec. 23, T. 1 S., R. 19 W., and farther east in secs. 10 and 11, T. 1 S., R. 18 W.

Economic interest in the Pierre shale lies mainly in the fact that possible commercial deposits of bentonite occur in the lowermost part of this formation. In fact, the bentonite zone lies so close to the Niobrara-Pierre boundary that some difficulty was encountered in determining to which formation it belongs. In the NW sec. 11, T. 1 S., R. 18 W., more than a foot of unmistakable black Pierre shale was found beneath the bentonite zone. Likewise, Pierre shale occurs below the bentonite exposures in the side of a ravine in NE sec. 35, T. 1 S., R. 20 W.

The Niobrara section in Phillips County has a maximum thickness of about 650 feet. The base is exposed in the southeast part of the county and the top is found in the northwest part of the county where the Niobrara-Pierre contact occurs. The Niobrara-Ogallala contact is not, of course, the top of the Niobrara, because the Ogallala formation was deposited unconformably on eroded and truncated Niobrara beds. This contact is much lower stratigraphically in the Niobrara in the southern and northeastern parts of the country than it is near the northwest corner.

The Niobrara, as elsewhere in Kansas, consists of a lower massive chalk zone known as the Fort Hays member (pl. 2A) and the upper Smoky Hill chalky shale member. A good section of the Fort Hays chalk is exposed at an old quarry in the NW corner sec. 29, T. 5 S., R. 17 W. Here, the member consists of 5-foot beds of unusually white chalk. Much better exposure of this member is found a short distance over the line in Smith County in the SW corner NW sec. 36, T. 4 S., R. 15 W. Here, about 40 feet of white chalk is exposed on both sides of a road cut in state highway 9. The total thickness of the Fort Hays in this part of Kansas is about 50 feet. The upper few feet are gradational between the typical thick chalk beds of this member and the thinner shaly chalks of the overlying Smoky Hill member. Foraminifera are abundant in the bottom 10 feet of the Fort Hays limestone.

Plate 2A--Fort Hays chalk overlying Carlile shale in northern Rooks County, SW SW sec. 1, T. 6 S., R. 18 W.

The Fort Hays localities in Phillips County are largely confined to the region of the Stockton anticline, between the Faubion oil pool just south of the county line in Rooks County and the town of Glade. The rest of the county, where erosion has stripped off the loess and Ogallala formations, is floored by soft chalky shale of the Smoky Hill member. These beds tend to erode in typical badlands topography, so that after the soil cover has been removed the land soon becomes valueless for crop raising and even for pasturing. It produces striking scenery, however, for many of the layers in the Smoky Hill member weather to bright yellow and orange colors so that the buttes and pinnacles produced are brilliantly colored (pl. 2B).

Plate 2B--Smoky Hill chalk exposure in SW corner sec. 34, T. 2 S., R. 17 W.

Although underlying the entire county and at no great depth in the southeastern part, only one exposure of the Carlile formation was found. That is in SE SW sec. 36, T. 4 S., R. 18 W. Here the combination of the north-south-trending Stockton anticline with the low topographic position created by the valley of the north fork of Solomon River has brought a few feet of Carlile shale to the surface. The very top of this formation is also found a little less than a mile south of the Phillips County line in a ravine in the Faubion oil field in SE SE sec. 1, T. 6 S., R. 18 W. Exposures are abundant to the south in Rooks County along the valley of the south fork of Solomon River and to the east in Smith County in the lower valley of the north fork of Solomon River.

The upper part of the Carlile shale is a black noncalcareous shale, and a sandstone known as the Codell occurs at the top. The Codell in this part of the state is only a few inches thick and is of no commercial value except as a distinctive marker for the Carlile-Niobrara contact.

The regional dip of the bedrock formations in Phillips and adjacent counties is 8 to 10 feet per mile northward. Plunging northward down this monocline in the east-central part of Phillips County is the Stockton anticline. While this anticline does not destroy the general northward dip of the formations, it does modify the picture considerably, creating northeast dips on the east side of the axis and northwest dips on the west side.

One notable effect of the Stockton anticline is to bring up to the surface the Fort Hays member of the Niobrara formation in the southern part of the county. At one place, previously mentioned, even the underlying Carlile is exposed. Fort Hays exposures are common in that general area, and along the south boundary of the county in the SE corner T. 5 S., R. 18 W., in the SE corner NE sec. 3, T. 5 S., R. 16 W., in the SE SW sec. 19 in the same township, in the SW corner sec. 28, T. 4 S., R. 15 W., and in the NW corner sec. 29, T. 5 S., R. 17. At the last two localities the Fort Hays has been quarried. The Fort Hays and underlying uppermost Carlile strata are also exposed a mile south of the Phillips County line in the Faubion oil field, which lies close to the axis of the Stockton anticline.

Another large anticline, with a trend parallel to the Stockton, is the Cambridge, the axis of which is near the Norton-Decatur County line, one county west of Phillips County. Between these northward-plunging anticlines is a northward-plunging syncline, here named the Long Island syncline after the town in northwestern Phillips County. The axis of this downwarp crosses western Phillips County and reaches its lowest point in Kansas near Long Island. The effect of this fold has been to drop the Pierre shale so that it is exposed in the valley of Prairie Dog Creek for a distance of several miles, and so that the stratigraphically lower Niobrara crops out both upstream and downstream (see state geologic map). The Pierre formation is exposed in the SE corner NE sec. 35, T. 1 S., R. 20 W., and in the west bank of a ravine in SW sec. 23, T. 1 S., R. 19 W. Upstream at the latter place, in NW sec. 26, the Niobrara formation crops out at an elevation 15 feet higher. Either the dip on the flank of the Long Island syncline is unusually steep at this point or the Niobrara has been pushed up by a local anticline.

The Niobrara formation of Phillips County is faulted in a number of places, which is also characteristic of this formation in the upper Smoky Hill Valley. Seemingly this faulting is due to incompetency or brittleness of the chalk beds and it probably does not extend very far below the base of the formation. On the south side of the Phillips-Rooks County line near the center N line sec. 2, T. 6 S., R. 18 W., a fault in the Niobrara is exposed in a road cut. Thick-bedded massive chalk, undoubtedly belonging to the Fort Hays member, is faulted against thin-bedded chalk and chalky shale that is either uppermost Fort Hays or a part of the Smoky Hill member. This fault lies west of the axis of the Stockton anticline, and the west side of the fault is the dropped side. The fault zone itself is about one-half inch thick and the material in this zone is slickensided.

A small fault having an easily measurable displacement is exposed in the side of a draw in the southwest part of SE sec. 1, T. 6 S., R. 18 W. in the Faubion oil pool of Rooks County. The plane of this fault cuts through both lower Fort Hays and upper Carlile. The contact between these formations has been dropped about 3 feet on the east side of the fault. Several of the faults in southeastern Phillips County are marked by springs.

Phillips County is situated on the eastern flank of a broad buried arch known as the Central Kansas uplift, and on the western edge of the Salina basin. According to recent investigations (Koester, 1935), the Central Kansas uplift is a repeatedly

rejuvenated structural feature trending northwest-southeast across north-central Kansas.... It originated in pre-Cambrian time as a series of parallel batholiths and persisted as a positive element throughout much of Paleozoic time. Several periods of broad warping and erosion occurred during the Paleozoic Mesozoic eras.

The axis of the arch trends in a northwest-southeast direction across the western part of Norton County, deviating farther to the east near the southern edge of Norton County where it crosses the northeastern corner of Graham County and the northwestern corner of Rooks County.

The entire area of Phillips County lies on the eastern and northeastern flank of the uplift. Because of the decreasing elevation of the land surface eastward in the same direction as the dip of the subsurface beds, the depth to formations remains fairly constant across most of the county. The greatest depth occurs in local synclinal areas in the eastern part of the county. The highest well elevation recorded in the county is 2,233 feet, at the Cities Service Oil Company No. 5 Pinkerton well, located in SW NE SW sec. 29, T. 5 S., R. 20 W., in the southwest corner of the county. The lowest well elevation is 1,687 feet, at the Frost Drilling Company No. 1 Hull well, SW SE sec. 25, T. 4 S., R. 16 W., in the southeastern part of the county.

The highest elevation of the Precambrian surface found to date in the county is 1,430 feet below sea level, in the Cities Service Oil Co. No. 2-B Johnson well, located in NE NW SW sec. 32, T. 5 S., R. 20 W., in the southwest corner of the county, and the lowest elevation is 1,835 feet below sea level in the Phillips Petroleum Company No. 1 McKinley well, located in SE NE SW SE sec. 13, T. 5 S., R. 18 W., in the south-central part of the county. It is impossible to state closely the elevation on the Precambrian surface in the eastern and northeastern parts of the county because of very poor control. However, because of the considerable regional dip to the east which is interrupted locally only by small cross folds, it seems certain that the elevation on the Precambrian surface in the extreme northeastern part of the county is considerably less than has been found in any of the wells that have been drilled to date.

Data from drill cuttings form the chief basis for the following discussion. Where drill cuttings were not available, however, or where they were not complete, it has been necessary to supplement sample information with data taken from drillers' logs.

The subsurface units are correlated with the divisions recognized by Betty Kellet (1932). In most cases, the minor subdivisions are not recognizable over the entire area; however, several beds may be correlated accurately over long distances. These correlation points are recognized and used by oil geologists when examining samples, and a few zones are sufficiently outstanding in character that they may be recognized and logged by drillers. This makes possible the use of drillers' logs in correlating a few formations.

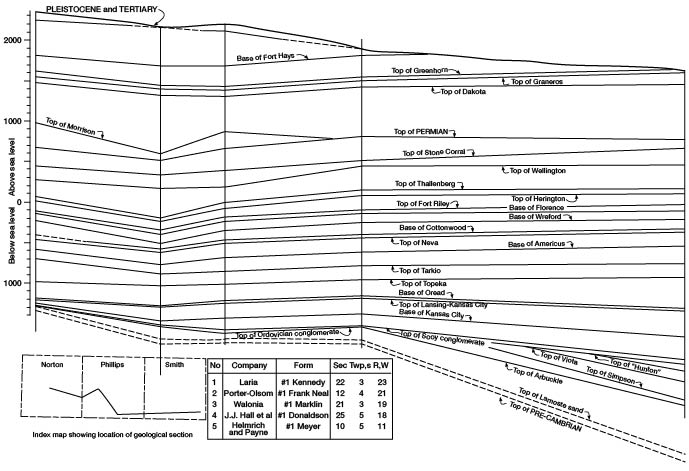

A fair degree of accuracy in correlating minor divisions may be obtained by reference to higher or lower beds that can be identified accurately. Even by this method it is almost impossible to recognize with certainty many of the small units. It is preferable, therefore, in this discussion to consider as units those rocks that are separated by fairly persistent marker beds. These units are defined by the top or bottom of recognizable beds in the accompanying geological section across east-central Norton County, southern Phillips County, and the southwestern part of Smith County (fig. 2).

Figure 2--Geological section across east-central Norton County, southern Phillips County, and southern Smith County.

The coarse sand that immediately overlies the Precambrian surface throughout western Kansas has been correlated with the Lamotte sandstone of Missouri and the Reagan sandstone of Oklahoma. Because of nearness to excellent exposures of Arbuckle rock in Missouri and the advanced state of classification of these rocks in the Ozark region of Missouri, it is desirable to correlate subdivisions of the pre-Mississippian rocks in Kansas with corresponding units that have been named in Missouri. Accordingly, the classification developed in the Ozark area, is used here, in so far as possible. Because the basal sandstone follows the irregularities of the Precambrian surface and underlies younger Paleozoic rocks progressively as they overlap on the flank of the uplift, it is obvious that this basal sand in places may be much younger than Cambrian. This is in agreement with Koester's (1935) opinion that "in wells near or on the uplift it is clearly Canadian or Ozarkian. Its correlation on the uplift with the Reagan or Lamotte is therefore untenable."

The maximum known thickness of the Lamotte sand is 53 feet in the Cities Service Oil Company No. 1 Ray well, located in the NE NW SE sec. 32, T. 5 S., R. 20 W. In places where the elevation of the Precambrian surface is much higher, the thickness of the Lamotte sand is considerably less; or, in places, the sand may be entirely absent. The Lamotte formation is a coarse-grained sandstone. The sand grains range from subrounded to angular and consist either of quartz or feldspar derived from the nearby granite that forms the core of the Central Kansas uplift.

The Lamotte sand is an important petroleum reservoir bed in a number of areas in western Kansas. The largest pool in Phillips County, the Ray pool, produces for the most part from the Lamotte formation.

Rocks of the Arbuckle formation underlie all except the extreme southwestern corner of Phillips County (fig. 2). Because of truncation of the Arbuckle beds high on the uplift, the thickness of Arbuckle rocks increases rapidly eastward and, locally, in synclinal areas even more rapidly. The maximum thickness reported in wells in Phillips County is 342 feet in the Lario Oil and Gas Company No. 1 Lynch Estate well, located in the CS SE SW sec. 24, T. 4 S., R. 20 W., in the southwestern part of the county.

Arbuckle rocks consist of coarsely crystalline sandy dolomite. Correlation of beds within the Arbuckle in Phillips County with those in other parts of the state is left to reports now in preparation.

Rocks of Ordovician age are absent over the greater part of Phillips County. However, in local synclinal areas both Simpson and Viola beds of Ordovician age are found.

Rocks of the Simpson formation are characterized by the presence of green shale and coarse, well-rounded, frosted sand grains. The maximum known thickness of the Simpson formation in Phillips County, 29 feet, was penetrated in the Helmerich and Payne No. 1 Loyd well, center east line SE SE sec. 6, T. 4 S., R. 17 W., in the southeastern part of the county. This thickness occurs in a local syncline, which extends into Phillips County from the east. Simpson rocks were removed by erosion from all but the eastern part of the county. This part of the county lies sufficiently far down the flank of the uplift that Simpson beds were not removed.

Rocks of Viola age have been reported in wells drilled in the east-central part of Phillips County. The thickness of the Viola rocks reported in the Helmerich and Payne No. 1 Loyd well, located in the center east line SE SE sec. 6, T. 4 S., R. 17 W., is 11 feet. Viola was also reported in the Carter No. 1 Munyon well, in sec. 5. T. 3 S., R. 16 W. Both of these wells have been completed so recently that samples are not yet available.

No known beds of Mississippian age have been encountered by the drill in Phillips County to date, although a considerable thickness of Mississippian rocks was found in the MidKansas Oil Company No. 1 Brogan, in the NE corner sec. 4, T. 2 S., R. 13 W., in Smith County. The relief on the pre-Mississippian beds is sufficient to indicate that Mississippian rocks have been removed from all but a very small area in the extreme east-central or northeastern part of the county.

Beds of Pennsylvanian age underlie the entire area of Phillips County at depths ranging from approximately 2,400 feet in the eastern part of the county to approximately 3,000 feet in the western part of the county.

The approximate thickness of Pennsylvanian rocks in Phillips County ranges from 900 feet in the southeastern part to 800 feet in the north-central part of the county. Beds of Pennsylvanian age become appreciably thinner in a westward direction from the eastern boundary of the county because of overlap on the pre-Pennsylvanian formations on the flank of the Central Kansas uplift.

Geologists familiar with the subsurface geology of western Kansas have found that there are five recognizable zones in the Pennsylvanian subsystem that are persistent throughout all of western Kansas. These are, in ascending order: top of the Sooy conglomerate, base of the Kansas City group, top of the Lansing group, base of the Oread formation, and top of the Topeka formation.

The top of the Sooy conglomerate marks rather indefinitely the top of the Pennsylvanian rocks of Marmaton or Cherokee age. The beds between the top of the Lansing group and the base of the Kansas City group in western Kansas probably include the beds classified as the Bronson group at the surface in the eastern part of the state. The beds between the base of the Oread limestone and the top of the Lansing group include the undifferentiated beds of the Douglas and Peedee groups. The beds between the base of the Oread and the top of the Topeka constitute the Shawnee group of the eastern part of the state. Immediately overlying the Topeka limestone is the Wabaunsee group, which includes the uppermost Pennsylvanian beds in western Kansas.

Because of the irregularity of the pre-Pennsylvanian surface, the thickness of the older Pennsylvanian beds is not constant over very great distances. The thickest beds were found in the east-central part of the county where a thickness of 256 feet of older Pennsylvanian beds is noted in Helmerich and Payne No. 1 Loyd well, located in the center east line SE SE sec. 6, T. 4 S., R. 17 S. This thickness undoubtedly would be considerably greater farther to the east, near the margin of the Salina basin.

The composition of the Sooy conglomerate differs considerably from place to place in the county. In the eastern part of the county, where the Sooy conglomerate immediately overlies beds of Ordovician age, a thick conglomerate zone consisting of material derived from the weathered Ordovician rocks is found. This is the "Ordovician conglomerate" of oil geologists. In these areas the chert is of smooth, white, weathered character, quite distinctive from that derived from the Arbuckle beds higher on the flank of the uplift. In areas where the Ordovician material is entirely absent and where cherts of Arbuckle derivation are not present, the chert is red, jasper-like, and highly weathered. It occurs in a matrix of red and green shale. In some places an abundance of fusulinids, similar to those in the lower Pennsylvanian rocks of eastern Kansas, show the Pennsylvanian derivation of a part of the material composing the Sooy conglomerate. In addition to chert fragments, large subangular sand grains are found cemented in a matrix of varicolored shale ranging from red to green or gray.

The beds between the base of the Kansas City group and the top of the Lansing group in western Kansas are predominantly limestone, but one or two thin, fairly persistent zones of red shale occur near the top. Studies now in progress indicate that further subdivision of the "Lansing-Kansas City" groups of western Kansas is possible.

The Lansing-Kansas City strata are the oldest Pennsylvanian beds that are continuous throughout the entire area of Phillips County. Beds of this age are considerably thinner over the higher points of the Central Kansas uplift than in adjacent structurally lower areas and in some wells less than 100 feet of those beds are present. To the eastward, down the flank of the uplift, the thickness increases appreciably to a maximum of 233 feet in the Helmerich and Payne No. 1 Loyd well, located in sec. 6, T. 4 S., R. 17 W., in the southeastern part of the county.

The Lansing-Kansas City rock division is one of the important oil-producing zones in western Kansas. Production is obtained from porous oolitic zones that occur near the top of the division. Two Phillips County pools, the Dayton pool and the Bow Creek pool, produce from the Lansing-Kansas City beds.

Rocks comprising the undifferentiated Douglas and Peedee groups occur between the top of the Lansing group and the base of the Oread formation. In Phillips County these beds are composed of red and gray shale and sandstone. A thin limestone logged in some wells between the top of the Lansing group and the base of the Oread formation may be the equivalent of the Haskell limestone.

The Shawnee group of eastern Kansas consists of the following formations named in ascending order: Oread limestone, Kanwaka shale, Lecompton limestone, Tecumseh shale, Deer Creek limestone, Calhoun shale, and Topeka limestone. The differentiation of the beds between the base of the Oread and the top of the Topeka in western Kansas is left to future studies. The western Kansas equivalent of those beds consists predominantly of limestone alternating with thin beds of red or black shale. A persistent black shale bed, a few feet above the base of the Oread, is correlated with the Heebner shale of eastern Kansas. This is a good marker bed over much of western Kansas.

Strata in western Kansas that commonly are correlated with the Wabaunsee group of eastern Kansas consist predominantly of alternating shale and thin limestone beds. A persistent fusulinid-bearing limestone in the lower part of this section is correlated with the Tarkio limestone of eastern Kansas.

Most subsurface geologists do not make an attempt to differentiate the uppermost Pennsylvanian beds from those of the lower Permian. The unconformity at the top of the Pennsylvanian and the base of the Permian is not easily recognizable in samples.

The terms Wolfcampian series and Leonardian series for the lower and upper subdivisions of the Permian in Kansas have been adopted by the Kansas Geological Survey. The Wolfcampian beds are characterized by the presence of alternating limestone and varicolored shale. The upper, or Leonardian, series is composed predominantly of shale beds, commonly red or gray, salt beds, and layers of gypsum or anhydrite.

Several persistent horizons or zones in the lowermost series of Permian rocks in western Kansas are recognized by subsurface geologists. These are, named in ascending order: base of the Americus limestone, Neva limestone, Cottonwood limestone, base of the Wreford formation, base of the Florence limestone, top of the Fort Riley limestone, Winfield limestone, Herington limestone, and Hollenberg limestone. These will be discussed in the order given.

Although most of the subdivisions of Permian beds recognizable at the outcrop doubtless are present throughout much of western Kansas, their differentiation becomes extremely difficult in well cuttings because of the thinness of the beds and because of the contamination of samples by material coming from higher beds while drilling is in progress.

The Americus limestone is a persistent stratigraphic unit, which is easily recognizable because of its position immediately overlying the shaly Admire group. The Americus is the lowermost member of the Foraker formation of the outcrop section. It is separated from the overlying Neva limestone by the thick Hughes Creek shale and by shale and limestone in the lower part of the Grenola formation.

The Neva limestone, which is the uppermost member of the Grenola formation of the outcrop section, is recognized by its position below the thick Eskridge shale, commonly more or less red, and above the Hughes Creek shale of the Foraker formation and lower shaly members of the Grenola formation.

The Cottonwood limestone is recognized by its position immediately above the Eskridge shale. It is separated from the overlying Wreford limestone by a considerable thickness of alternating limestone and shale beds in the upper part of the Council Grove group. The Cottonwood limestone is the lowermost member of the Beattie limestone formation of the outcrop section.

The persistent Wreford limestone is easily recognizable both because of the considerable amount of chert present and because of its position above the thick shale beds of the upper Council group and below the thick Matfield shale. The Wreford formation consists of three members: Threemile limestone at the base, Havensville shale, and Schroyer limestone. Both of the limestone members contain much chert. The relatively thin Havensville shale member is not commonly recognizable in subsurface studies.

The base of the Florence limestone, commonly logged as "Florence flint" by subsurface geologists, is easily recognizable by the presence of a large amount of a characteristic gray to blue fossiliferous chert. It is the lower member of the Barneston formation. Its position immediately above the thick Matfield shale also serves to make this unit distinct from lower beds.

The Fort Riley limestone, the upper member of the Barneston formation, is recognizable as being the first massive limestone below the upper Permian shale and anhydrite. It is separated from the Florence limestone by the Oketo shale, which is so thin throughout all of western Kansas that it is unrecognizable in either samples or drillers' logs.

The Winfield, Herington, and Hollenberg limestones are recognizable in drillers' logs principally by their position above the massive Fort Riley limestone and below the red shale, gray shale, and anhydrite of the lower Wellington. These beds consist of dolomite or dolomitic limestone. Because of the thinness of these deposits and the preponderance of red shale cavings and anhydrite from the overlying Wellington formation, they are difficult to log successfully in samples.

The lowest formation of the Leonardian series in Phillips County is the Wellington formation, which immediately overlies the Hollenberg limestone. This formation consists of anhydrite, red shale, and salt. Little is known about the thickness of the salt in Phillips County. Because of the solubility of salt, it is difficult to obtain samples when drilling wells with rotary tools. The thickness of the Wellington formation ranges from 200 to 300 feet, the thickest section occurring in the south-central part of the county.

Immediately above the Wellington formation is a thick bed of predominantly red shale known as the Ninnescah shale. The thickness of this formation is approximately 200 feet.

The Ninnescah shale is immediately overlain by rock known as the Stone Corral, which is a dolomite that in places contains considerable anhydrite. This formation is very persistent throughout western Kansas. Because of its position between two thick shale divisions, the Stone Corral is easily recognized, both in samples and by drillers. Consequently, it is an important marker bed through all of western Kansas.

The uppermost Permian rocks in Phillips County are the red shale and red sandstone of the Nippewalla group. The Nippewalla immediately overlies the Stone Corral throughout the entire county. The top of the Nippewalla in Phillips County marks the unconformity between beds of Permian and Jurassic (?) ages in the northern part of the county, and the unconformity between beds of Permian and Cretaceous ages elsewhere in the county.

Beds correlated with the Morrison formation of Jurassic age are found in the north half of Phillips County. These beds become thinner and pinch out southward. The maximum thickness found in wells drilled in Phillips County is 315 feet in the Frost Drilling Company No. 1 Hull well, located in SW corner SE sec. 25, T. 4 S., R. 16 W. These beds consist of red and green shale and reddish sandstone that are distinguishable from the overlying Cretaceous and the underlying sands and red shales of the Permian.

Subdivisions of beds of Cretaceous age commonly made by geologists working in Phillips County, are named in upward order: Dakota formation, Graneros shale, Greenhorn limestone, Carlile shale, Fort Hays limestone, and Pierre shale. Beds of Cretaceous age occur over the greater part of the county. The Cretaceous section is much thicker in the western part than in the east because of the eastward slope of the surface.

The Cretaceous beds in Phillips County, between the top of the Permian and the top of the Dakota formation, as indicated by samples from oil wells, seem to consist predominantly of sandstone. It is known from study of beds at the surface, however, that a relatively large amount of shale is present through the entire lower part of the Cretaceous section.

The Cretaceous of this area probably includes representatives of the Cheyenne sandstone and the Kiowa shale, below the Dakota formation. No attempt is made here to subdivide these lower beds.

The Graneros shale, immediately overlying the Dakota sandstone, is a dark-gray shale containing streaks of bentonite. The thickness of this shale is fairly uniform throughout the county, its average thickness being about 7 5 feet.

The Greenhorn limestone immediately overlies the Graneros shale and is persistent over the entire county. The Greenhorn consists predominantly of chalky limestone and contains an abundance of Foraminifera, among which species of Globigerina are most abundant.

The Carlile shale, which occurs directly above the Greenhorn formation, is a dark-gray shale. The average thickness of the Carlile shale is 260 feet. This formation is present in most of Phillips County.

The Fort Hays limestone, immediately above the Carlile shale, is a chalky limestone that lies at the base of the Niobrara formation. The Fort Hays member ranges in color from dark gray to white. The thickness is approximately 40 feet. The Niobrara formation immediately underlies the Pierre shale.

The Fort Hays limestone occurs at the surface in the eastern and southern part of Phillips County but in the western part is covered to considerable depth by overlying younger Cretaceous and Quaternary beds.

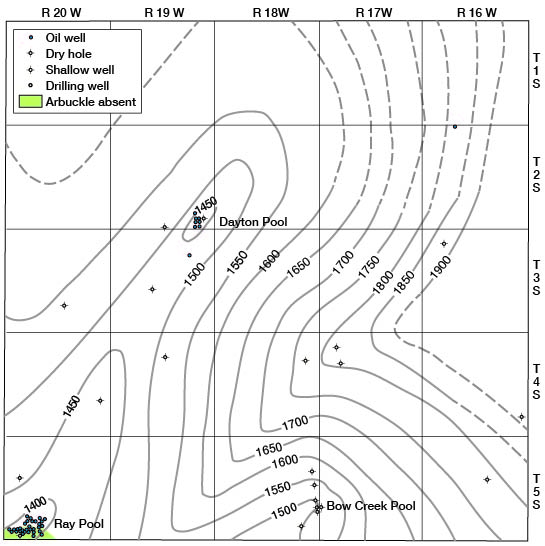

A structure contour map drawn on the top of the Arbuckle group (Fig. 3) indicates that the most prominent subsurface structural feature present in Phillips County is an anticline, the axis of which extends in a northeast-southwest direction across Phillips County. It intersects the southern line of the county in the extreme southwestern corner of the county. This anticline is flanked on the northwest by a syncline, and on the southeast by another, which is probably a westward extension of the Salina basin.

Figure 3--Structure contour map of Phillips County drawn on the top of the Arbuckle formation.

The point of highest elevation on the Arbuckle beds is in the extreme southwestern corner of the county at the contact of the Arbuckle and the Precambrian surface. A less pronounced "high" is indicated in the southeastern part of T. 5 S., R. 18 W.

The relief on the Arbuckle surface is more than 450 feet. The lowest point known is in the SW corner sec. 5., T. 3 S., R. 16 W. in the Carter Oil Company No. 1 Munyon well.

The Arbuckle surface dips from the crest of the anticline noted above southeastward at a rate of approximately 30 feet per mile and northwestward at a rate of approximately 35 feet per mile. The anticline plunges northeastward at a rate of about 5 feet per mile. Lack of control in the northern part of Phillips County prevents reliable determination of the configuration of the top of the Arbuckle in that part of the county. Future drilling will undoubtedly necessitate significant changes in the map of the subsurface of that part of the county. It is significant to note that each of the three oil pools that have been discovered to date in Phillips County are either on the crests of the small high in the south-central part of the county or along the axis of the anticline.

The axes of both of the high areas in Phillips County extend in directions transverse to the axis of the Central Kansas uplift.

Three oil fields have been discovered in Phillips County up to the present time. These are, named in order of importance: Ray pool, Dayton pool, and Bow creek pool. No gas in commercial quantity has been produced as yet in the county.

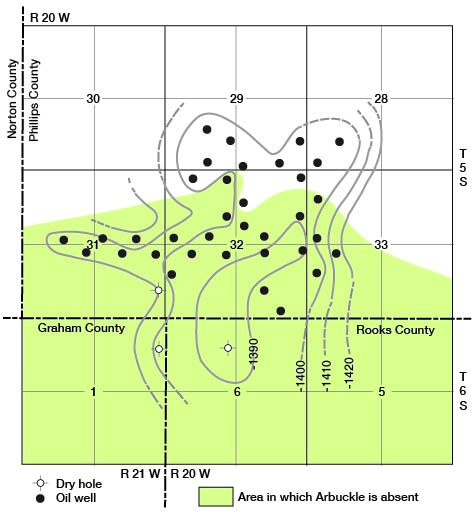

The Ray pool is located in secs. 28, 29, 31, 32, and 33, T. 5 S., R. 20 W., in the extreme southwestern corner of Phillips County. The total area of the pool is about 1,100 acres. Production is obtained from the Lamotte sandstone from the Arbuckle dolomite.

Accumulation of oil in the Ray pool is due to the wedging out of the Lamotte sandstone and the Arbuckle dolomite against the Precambrian surface on the Central Kansas uplift. At the present time there are 35 producing wells in the pool, of which 10 produce from Arbuckle beds and 25 from the Lamotte "sand." A structure map of the pay zone is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4--Structure contour map of the pay zone in the Ray pool.

The discovery well for the Ray pool was the Cities Service No. 1 Ray well, located in the NE NW SE sec. 32, T. 5., R. 20 W. This well was completed in July 1940, and was given a state potential of 2,135 barrels of oil per day. Most of the wells in the Ray pool are maximum wells.

At the present time the Ray pool is limited only to the south where the Lamotte is too thin for commercial production. The pay zone is thin or absent in three wells, one of which is located in sec. 6, T. 6 S., R. 20 W., another in sec. 1, T. 6 S., R. 21 W., and the third in the SE corner sec. 31, T. 5 S., R. 20 W. No other dry holes have been drilled in the area. There is, therefore, room for several locations around the other sides of the pool, all of which would offset wells capable of producing over 1,000 barrels of oil a day.

The discovery well for the Dayton pool was the Carter Oil Company No. 1 Friebus, located in the center west line SW NW sec. 36, T. 2 S., R. 19 W. This well was drilled to the granite, then plugged back to the Lansing-Kansas City zone. It was completed June 6, 1941, and was given a potential of 328 barrels of oil per day. All the wells in this pool produce from the Lansing-Kansas City at a depth of approximately 3,300 feet below the surface. Production is found in porous oolitic beds. At the present time there are five oil wells and two drilling wells in the Dayton pool.

One dry hole in the NW sec. 36, T. 2 S., R. 19 W. may limit the Dayton pool to the east. One other dry hole almost 2 miles to the west, in the SE corner sec. 34, T. 2 S., R. 19 W., may limit the pool in that direction. No other dry holes have been drilled within a significant distance. There is, therefore, room for several locations around the periphery of the pool.

The discovery well for the Bow Creek pool was the Blue Stem Oil Company No. 1 Donaldson well, located in the SE NE NE sec. 25, T. 5 S., R. 18 W. This well was completed June 7, 1939, and was given a potential of 820 barrels of oil per day from Lansing-Kansas City beds at a total depth of 3,164 feet. To date, three dry offsets have been drilled surrounding the discovery well.

The greater part of Phillips County has not yet been adequately tested by the drill. Thirteen townships that have not had as much as one well remain to be tested and nine others have had but one well each. A number of the wells were not drilled to a sufficient depth to test all of the possible producing formations in the county.

Most of the drilling activity to date has been concentrated in areas along the crest and flanks of the anticline in the central part of the county and in the area of the Bow Creek pool.

Two wells on what seems to be the crest of the Stockton anticline, one located in the NE corner SW sec. 21, T. 3 S., R. 19 W., and the other located in the center south line SE SW sec. 24, T. 4 S., R. 20 W., were unsuccessful. Both of these were drilled to the Arbuckle dolomite. These two wells, however, are the only dry holes that have been drilled along the crest of the anticline which extends from the Ray pool in the southwestern corner of the county to the Dayton pool in the SE corner of T. 2 S., R. 19 W.

Oil from the Ray pool is transported by pipeline to the refinery of the Cooperative Refinery Association at Phillipsburg, which has a capacity of 3,000 barrels of crude oil per day. The oil from the Dayton pool is transported by truck to the same refinery. In addition to oil obtained in Phillips County, the refinery also obtains oil from the Layton pool in Rooks County.

Bentonite, which is a clay or claylike material derived from the alteration of volcanic ash and which has a variety of commercial uses, occurs in Phillips County in an outcrop belt ranging in width from one-half to three-fourths of a mile and extending from 3 miles due south of Long Island to sec. 11, T. 1 S., R. 18 W. The location of the best exposures of bentonite are shown in figure 5. At some places the bed reaches a thickness of as much as 20 feet. A somewhat detailed description of the bentonite of Phillips County was given in Bulletin 41, part 3 (1942), and a study of the physical properties and uses of Kansas bentonite is now being carried on by the State Geological Survey.

Figure 5--Map showing location of bentonite deposits in Phillips County.

Phillips County contains but one known volcanic ash deposit of commercial size. This lies southwest of Speed on the Beckley farm in the east half and northwest quarter of sec. 33, T. 5 S., R. 19 W. (Landes, 1928, p. 39, 40). It is one of the first, if not the first, volcanic ash beds to be worked in the state. A mill was erected there some time before 1900. Only the foundations of this mill were left when the property was leased on February 2, 1900, for a period of 99 years. This lease is now assigned to the Pumicite Company, but there has been no production of ash for many years. The deposit has been estimated to contain 500,000 tons. The ash is of Pleistocene age and is white.

The so-called "blue" ash, of Tertiary (?) age, occurs in at least two places in the northern part of Phillips County. One locality is on the north side of the NW sec. 9, T. 2 S., R. 17 W. Here a bed of fine volcanic ash, 28 inches thick, the uppermost 2 inches calcareous, is exposed in a road cut beneath a 6-inch Tertiary (?) limestone. This stone is covered by 3 feet of soil. Along the east side of the road in the NW sec. 25, T. 2 S., R. 19 W., 30 inches of gray volcanic ash grading into sand at the base is exposed in a road cut and nearby shallow ravine. This deposit is overlain by a 3-inch zone of calcareous nodules and 6 inches of soil.

The stone resources of Phillips County include both the Fort Hays and Smoky Hill chalk members of the Niobrara formation of Cretaceous age and the Ogallala formation of Tertiary age. Beds in both the Smoky Hill member and Ogallala formation have been silicified in part and most of the commercial production of stone in the county has been of such material.

The Fort Hays limestone has been quarried for building stone where the member is brought up by the Stockton anticline. One locality is in the SE SW sec. 36, T. 4 S., R. 18 W., where the entire basal portion of the Niobrara is exposed on the face of the cliff lying on the east side of a gully tributary to north fork of Solomon river. The Fort Hays has also been quarried southwest of Glade along the south side of Solomon River valley and in the NW corner sec. 29, T. 5 S., R. 17 W., where massive 5-foot beds of unusually white chalk have been uncovered. Recent investigations by the State Geological Survey on the quality of the chalk exposed in southwestern Smith County led to the exploitation of this material. The chalk beds of southern Phillips County seem to be of comparable grade.

One building stone use of unsilicified Smoky Hill chalk was noted. It has been quarried in the northeastern part of Phillips County for flagstone. About 0.4 mile east of the NW corner sec. 30, T. 2 S., R. 16 W., an 8-inch dense chalk bed is exposed south of a pond dam. This bed, which has been quarried to a small extent for use as flagstone, is similar in thickness and somewhat resembles the famous "postrock" so widely utilized in north-central Kansas. It has been "case hardened" at the base but is much softer, even somewhat "punky," at the top. The same or a very similar bed is exposed near the center of the SW sec. 24, T. 2 S., R. 17 W. (pl. 3A). In this vicinity both flagstone and a higher bed of silicified chalk are quarried. In utilizing the flagstone it has been the custom to trim off the upper soft part, yielding stones about 4 1/2 inches thick.

Plate 3A--Niobrara flagstone quarry near center of SW sec. 23, T. 2 S., R. 17 W.

The quarrying of silicified chalk is a new industry in northwestern Kansas. In widely scattered localities throughout this area, the shaly chalk of the Smoky Hill member of the Niobrara formation has been partially or entirely replaced by silica. This replacement, like petrification of wood, has taken place without changing the color or general appearance of the original material. Where the original chalky shale was yellow, orange, or red, as is true of much of the chalk in this part of the section, the silicified chalk has the same color. It is, of course, many times harder, and cannot be scratched with a knife where nearly complete silicification has occurred. The rock is also very brittle, breaking with a conchoidal fracture. The source of the silica deposited in solution was probably the highly siliceous Tertiary and perhaps younger materials, which at one time veneered the surface throughout this area.

The most extensive exploitation of silicified chalk in Phillips County has been in the NW sec. 23, T. 2 S., R. 17 S. (pl. 3B). Here, a large scale W.P.A. project, sponsored by the county, has been carried on. In this vicinity are three sets of quarries: on the west side of a ravine where the rock crusher is located; directly across from the rock crusher, on the east side of the ravine; and southeast of the last-mentioned locality, along a tributary gully. The maximum thickness quarried at the first locality is 8 feet. All stages of replacement, from no replacement whatever to nearly 100 percent, were noted in the faces of these quarries. Not only are the colors, such as white, yellow, buff, and brown, of the original chalk retained in the silicified beds, but also considerable chalk shows various shades of green. As green is not a normal color of the chalk, it is assumed that this hue is due to the presence of ferrous iron in the ground water descending from the overlying siliceous beds. In some instances replacement was by layers, but it was also found that some replacement was in the form of lenses or very irregular masses with apparently little or no conformation to the stratification.

Plate 3B--Silicified chalk quarry, NW sec. 23, T. 2 S., R. 17 W.

The silicified chalk quarry near the center SW sec. 24, T. 2 S., R. 17 W., was mentioned in a preceding paragraph.

Where silica-bearing solutions have penetrated the Ogallala formation, the original sandstone has been so silicified as to form a true quartzite. The fracture, although conchoidal in type, makes a fairly smooth break through sand grains and cement alike. The color of this rock is green, no doubt due to the presence of ferrous iron in the silica-depositing solutions. The Ogallala quartzite is an exceptionally durable rock. It is harder than limestone and very resistant to abrasion. It contains little or no mineral matter vulnerable to alteration or decay through the action of atmosphere or water.

The largest deposit of quartzitic Ogallala beds is in the northwest corner of the county. During the summer of 1939 the Tobin quarries in the north half of the SE sec. 5, T. 1 S., R. 19 W., were being worked (pl. 4A). The zone of quartzite worked here is about 12 feet thick. Nearby in the SE NW sec. 4, T. 1 S., R. 19 W., are older abandoned quarries. It has been reported that the rock from these old quarries was used in paving Lincoln, Nebraska. Other, but unexploited, deposits of this rock cap the hills to the southeast in the vicinity of sec. 6, T. 2 S., R. 17 W.

Plate 4A--Silicified Ogallala quarry in the N/2 SE sec. 5, T. 1 S., R. 19 W.

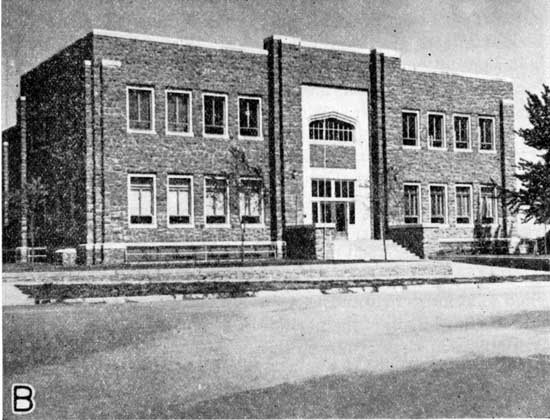

South of the north fork of Solomon River, the uplands are capped by the Ogallala formation in the western half of the county, and in at least two localities this formation has been made quartzitic by the action of ground water. The stone used in the community building in Phillipsburg (pl. 4B) was quarried in the NW sec. 15, T. 5 S., R. 18 W. This material is very similar in appearance to that obtained in the northwestern part of the county. In the NE corner sec. 23, T. 5 S., R. 19 W., the same type of rock has been quarried and stock-piled at several places on both sides of the county road.

Plate 4B--Phillipsburg community building, constructed with silicified Ogallala stone.

A so-called "soft sandy lime" is exposed in the north half of the NW sec. 33, T. 1 S., R. 16 W. This material also occurs in the road ditch on the north side of the road, 0.3 mile from the SW corner sec. 28, in the same township. Although less gritty and containing more calcium carbonate than the average Ogallala material, this bed belongs in that formation. It is planned to use this rock for road surfacing on the county highway system.

Most of the sand and gravel production in Phillips County has been in the western part of the county. All of the deposits examined are of the high terrace type, owing their origin to deposition in ancient streambeds which had steeper gradients than the streams draining this part of the state today. These streams, therefore, were floored with relatively coarse sediment. One commercial sand pit is in the NW sec. 33, T. 4 S., R. 19 W. The deposit has a maximum thickness of 15 feet. It consists of quartz and granite sand grains associated with some pebbles up to 4 inches in diameter. The pebbles are mostly chalk, but make a small percentage of the total.

A gravel deposit having a maximum exposed thickness of 21 feet, near the NE corner sec. 26, T. 2 S., R. 20 W., has been exploited in the past. Many of the pebbles have a diameter range between 1 and 2 inches, with a maximum of 4 inches, but the average is closer to one-half inch. Quartz, chalk, jasper, and other types of chalcedony, granite, and quartzite were among the minerals and rock fragments identified in the pebbles. Obviously this deposit is a mixture of sediment derived from the Rocky Mountains and fragments from local chalk beds. The gravel is crossbedded and an unconformity occurs at the top. Above the gravel is darker-colored fine sand containing a few pebbles. This upper zone is as much as 4 feet thick. Similar quarries are in the SW sec. 24 in the same township.

Another gravel pit is located in the SE corner NE sec. 1, T. 1 S., R. 20 W. This deposit immediately overlies Niobrara bedrock, and the sand at the base is filled with water. The "gravel" is mostly sand, rounded quartz grains predominating. Within the sand are irregular gravel zones containing pebbles up to 6 inches across. Most of the pebbles are chalk, and some are silicified. The maximum thickness of this deposit is 18 feet. The overburden is thin and consists of loess.

In common with other counties in northwestern Kansas floored largely by the Niobrara formation, Phillips County is not too well supplied with water-yielding formations (aquifers). For a discussion of the water-bearing formations of Kansas, the reader is referred to Moore (1940). The wide belt of alluvial deposits underlying the floodplain of the north fork of Solomon River is the most productive source of ground water in the county. Water occurs in the coarser lenses of sand and gravel composing a part of the alluvial deposit. The municipal and railway supplies of Phillipsburg are obtained from wells dug into the alluvium on the south side of the river. From the wells the water is pumped approximately 6 miles into Phillipsburg. Logan, Speed, and Kirwin likewise obtain their supplies from the alluvium beneath the floodplain of Solomon River, on which they are located. Long Island, near the northwestern corner of the county, obtains its water from the belt of alluvium along Prairie Dog Creek. Obviously, the farmers living along these stream flats have little difficulty in obtaining water for domestic and stock use.

In the vicinity of Phillipsburg and southeast of the townsite, the residents are fortunate in that a coarse high terrace sand, as shown in Plate 1A, lies beneath the soil mantle and directly on top of the impervious Smoky Hill chalk bedrock. It has been reported that wells drilled into this sand yielded supplies of water adequate for domestic or stock use even during the worst drought years (Richards, B. H., Jr., personal communication).

Over much of the upland part of the county, ground water is much more difficult to obtain. The Ogallala is a very important water-bearing formation in western Kansas in counties that are covered by a considerable thickness of this porous formation. As pointed out above, however, in Phillips County a large part of the Ogallala formation has been removed by erosion, so that thin patches of the formation remain only in the uplands in the northern, western, and southwestern parts of the county. The maximum thickness of the Ogallala in these parts of the county probably does not exceed 50 feet. The Ogallala is sufficiently thick over most of this upland area to provide adequate supplies for farm use, however. The community of Prairie View is supplied from wells that tap the Ogallala.

The principal source of water in the Ogallala is a zone of sand at the base of the formation, immediately overlying the relatively impervious Smoky Hill member of the Niobrara formation. It may be counted on as a source of water almost everywhere in the parts of Phillips County in which the Ogallala formation is present in any appreciable thickness.

The chalks and chalky shales of the Niobrara formation are notably poor water bearers, for the consistently fine texture of these rocks prevents the passage of water. The only exception occurs where the chalk beds are fractured and water occurs in cracks in the otherwise impervious rock. A few farm wells obtain water from such cracks and fissures, but as there is no rule covering the occurrence of such openings, finding water under these circumstances is a matter of luck. In a few places water has accumulated in fault zones. A spring that issues from a fault in the SW sec. 32, T. 3 S., R. 15 W., has yielded, according to local reports, a tankful of water a day for more than 35 years. Most of the farmers in the outcrop area of the Niobrara have to utilize surface ponds or depend upon shallow wells dug to the base of the thin soil zone where some accumulation of ground water may have taken place. The latter source of supply is very unreliable as a general rule.

In some parts of western Kansas the Codell sandstone, which lies below the base of the Niobrara formation at the top of the Carlile shale, is sufficiently thick and coarse to yield water to wells. In practically all, if not all parts of Phillips County, however, the Codell sand is much too thin to yield appreciable quantities of water. The underlying Carlile and Greenhorn formations consist of impervious shale and thin beds of chalk, neither of which carry water. The still deeper Dakota formation is an important aquifer in parts of the Great Plains area. In northern Kansas, however, the water in the Dakota is too strongly mineralized to be usable for drinking. A well drilled into the Dakota formerly was used as a source of water for the swimming pool on the west side of Phillipsburg, but the pool has been abandoned. The water from this well is rather closely similar in composition to the mineral water from Waconda Springs in Mitchell County, which also comes from the Dakota formation. Highly mineralized water was obtained in a well drilled to the Dakota on the Jackson farm in SE sec. 28, T. 5 S., R. 18 W.

Frye, J. C., and Hibbard, C. W., 1941, Pliocene and Pleistocene stratigraphy and paleontology of the Meade basin, Kansas: Kansas Geological Survey, Bulletin 38, pt. 13, p. 389-424, figs. 1-3, pls. 1-4. [available online]

Jewett, J. M., Schoewe, W. H., and others, 1942, Kansas mineral resources for war-time industries: Kansas Geological Survey, Bulletin 41, pt. 3, p. 69-180, figs. 1-13.

Kellett, Betty, 1932, Geologic cross section from western Missouri to western Kansas: Kansas Geological Society, Sixth annual field conference, 1 pl.

Koester, E. A., 1935, Geology of the central Kansas uplift: American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Bulletin, v. 19, p. 1405-1426, figs. 1-5.

Landes, K. K., 1928, Volcanic ash resources of Kansas: Kansas Geological Survey, Bulletin 14, p. 1-58, pls. 1-5, figs. 1-3. [available online]

Moore, R. C., 1940, Ground-water resources of Kansas: Kansas Geological Survey, Bulletin 27, p. 1-112, figs. 1-28, pls. 1-34. [available online]

Smith, H. T. U., 1940, Geologic studies in southwestern Kansas: Kansas Geological Survey, Bulletin 34, p. 1-212, figs. 1-22, pls. 1-34. [available online]

Kansas Geological Survey

Placed on web Aug. 19, 2011; originally published in August 1942.

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

The URL for this page is http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/Bulletins/41_8/index.html