Kansas Geological Survey, Educational Series 6, originally published in 1988

Previous Page--Fossils ||

Next Page--Maps, Glossary

Acansis, Canips, Caw, Ka Anjou, Kathasi, Kauzaus, Konga, Quaus, Ukasak. These are just a few of the ways early explorers spelled the name of an Indian tribe they found living in central North America. Because the Indians had no written language, their name had no official spelling. French explorers spelled it the way they thought it should be spelled in French, the Spanish based their spellings on Spanish, and the Americans used English. Later settlers named the territory after the Indians. They called it Kansas.

Just as Kansas has had many names, it also has many faces. Not all areas of Kansas are alike. Some areas are hilly, others are flat. Some parts have more rainfall and rivers, which means more trees and bushes. In areas with less rainfall, fewer trees and more prairie grasslands are found. In some areas the dirt is brown. In other parts it is red. Some places have water stored in rocks underground, while in other areas, ground water is not so plentiful.

The landscape in Kansas hasn't changed much in the past 4,000 to 5,000 years. The biggest changes have been made by the people who have made Kansas their home. Although the Indians did affect the environment, they lived more in harmony with nature. When settlers moved in, the big changes began.

Farmers plowed the soil and the prairie grasslands began to disappear. Holes and ditches were dug in the earth in search of minerals and building materials. Roads and buildings were constructed, and cities and towns grew. Most of this happened in just the past 150 years.

Today the Kansas landscape is a combination of natural landforms and human-made features. Natural landforms are features of the Earth such as hills, mountains, valleys, slopes, canyons, sand dunes, plains, and plateaus.

The landscape looks the way it does because of geologic activities in the past. In some places limestone is the rock at or closest to the surface and in other places sandstone is on top. In some areas hills were carved out by rivers that eroded the land. In other places, large rivers meandered around and flattened out the land for miles in all directions. Large slabs of rock are near the surface in some regions, making the soil rocky, while other regions have several layers of soil and sediment above the rock.

The state has been divided into regions based on rock type and age, landscape, and landforms. Some regions look alike but the rocks and soil in the regions were formed at different times. Differences also are found within a single region. Hilly regions have flat areas and flat regions usually have a few hills. The variety of landscapes and landforms in Kansas may surprise you.

Many people still form their opinion of Kansas by watching a Hollywood movie made in 1939. The Wizard of Oz, which, by the way, was not filmed in Kansas but in a Hollywood studio, depicts Kansas as hot, dry, dusty, flat, and tornado-ridden. The Ozark Plateau region, in the southeast corner of the state, doesn't come close to fitting this image.

This region of Kansas is the corner of the Ozarks, a hilly and densely forested region that covers a large area in Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. The limestone and flint in this region were formed during the Mississippian Period, 350 million years ago. They are the oldest surface rocks in the state.

Two minerals, lead and zinc, were once mined in this area. Rocks were crushed to get the minerals out. The lead and zinc are no longer mined here, but big piles of crushed rock called "chat" were left behind.

Figure 30. Tailings piles in Cherokee County.

The region northwest of the Ozark Plateau, the Cherokee Lowlands, differs from the Ozark Plateau in appearance. The Lowlands aren't as hilly as the Plateau and don't have as many trees, but the two regions have similar mining and industry backgrounds.

In the late 1800's and early 1900's, business was booming in southeast Kansas. Growth was based on thriving industries, such as coal mining and the cement, glass, brick, and tile plants that popped up around the area. All of these industries used the natural resources such as coal, zinc, clay, and limestone. But by the 1930's, many of the industries closed because they were no longer profitable. Some industry still exists in southeast Kansas and coal is still mined, but the mineral-based industrial heyday is over.

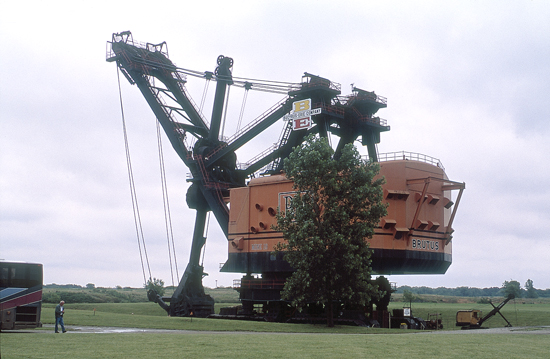

In Kansas, coal is removed by strip mining. Large, mechanical shovels are used to dig long, deep ditches to reach the underground coal. One of the world's largest shovels, Big Brutus, was used in Cherokee County. Big Brutus is retired from mining now and is used as a museum.

Figure 31. Big Brutus is 160 feet tall from the ground to the top of the boom. This distance is about equal to the height of a 15-story building.

Companies must smooth out these ditches and plant trees and grass when they are finished mining. This is called land reclamation. After the land is leveled, it can be used for other things, such as farming and grazing.

Before 1969, companies didn't have to reclaim the land. Land that was not reclaimed can still be seen. Many of the abandoned ditches are now filled with water and have been stocked with fish.

North of the Cherokee Lowlands is the Osage Cuesta (pronounced kwesta) region. This area was once covered with shallow seas. During the Pennsylvanian and Permian periods, about 230 to 310 million years ago, these seas would grow and shrink due to sea-level changes. The changes were caused in part by fluctuation in the amount of ice in the polar ice caps. When more of the Earth's water was frozen at the poles, world-wide sea levels in other areas would drop. Sometimes the Kansas seas completely disappeared. When some of the ice at the poles melted and water was released, water levels rose again.

Today the sea level is lower than during the Pennsylvanian and Permian periods and land in the area has been uplifted, or raised, by changes in the Earth. Lower sea levels and higher land caused the seas to retreat. The rocks formed from sediment deposited by the seas were then buried several thousand feet. Uplift and erosion have now exposed these rocks and formed hills, called cuestas.

Cuestas have a steep slope on one side (an escarpment) and gentler slopes on the other sides. Cuesta is the Spanish word for cliff.

Figure 32. These cuestas are near Pomona. The arrow points to a steep slope called an escarpment.

The Osage Cuestas are composed of several alternating layers of sandstone, limestone, and shale. Not all of the hills in the Osage Cuesta region are cuestas with escarpments. Rolling hills and flat areas also can be found. Like all regions in the state, the cuesta region has variety.

West of the Osage Cuestas are the Chautauqua Hills, known for their thick layers of sandstone and usually densely vegetated with oak and other timber. During the Pennsylvanian and Permian periods, rivers and streams flowed into the sea in this area. Sand and other sediment collected at the mouths of the rivers, forming deltas. When the seas dried up, the sediments were buried and formed rocks. The sands became sandstone and the muds became shale. Uplift and erosion eventually exposed sandstone and shale outcrops at the Earth's surface.

Figure 33. Orso Falls in Chautauqua County is created where the Caney River runs over a limestone ledge.

Several glaciers, which are huge masses of ice, covered much of the northern United States hundreds of thousands of years ago. The glaciers grew and melted as the climate changed. Most of the glaciers did not reach Kansas, but at least two dipped down into the northeast corner. When the glaciers retreated, rocks and soil that had been carried into the area from the north were left behind. The force of the moving ice was so strong, it broke large quartzite boulders off outcrops in South Dakota, Iowa, and Minnesota and carried them over 200 miles into Kansas. The boulders can still be seen scattered throughout the area today.

Figure 34. Boulders, carried into northeast Kansas by glaciers, were deposited on a hill near Wamego.

The glaciers also left behind a layer of sediment. Finely ground silt, called loess, was sorted and carried by the wind. Thick layers of loess were deposited throughout the area. Fertile soils formed from loess are good for farming because they contain few rocks.

Figure 35. Gentle hills of loess farmland in Doniphan County.

When settlers first moved to Kansas, many of them passed the Flint Hills by. They wanted good farmland, and the rocky soil was too hard to plow. Although the area is now used for grazing cattle, not much of the land has been plowed to grow crops, and the Flint Hills remain, for the most part, a natural prairie grassland.

Figure 36. In 1868, the state began paying ranchers to build fences to keep cattle from roaming freely. Thousands of miles of limestone fences were built in the Flint Hills, including this stretch along K-99.

The Flint Hills region, which runs north and south through east-central Kansas, is one of the few large areas of native prairie grassland left in the United States. The grassland that covers the Flint Hills once covered most of central and western Kansas and the surrounding states. When people moved in, the prairie in other areas became covered with farms and cities. Away from the roads and buildings, the Flint Hills region looks much as it did 10,000 years ago.

Although the Flint Hills region is known for its rolling grasslands, it is named for flint, a type of rock that is found embedded in the limestone that forms the hills. Flint, also called chert, doesn't erode as easily as the softer limestone. When the limestone at the surface is eroded by wind and water, it eventually breaks down into soil. The exposed flint is broken down into gravel, which mixes with the soil and makes the ground rocky.

West of the Flint Hills is another hilly region called the Smoky Hills. The rocks in the Smoky Hills, like those in the Osage Cuestas, were formed from sediment deposited on or near a sea floor. While the Osage Cuestas were formed earlier during the Pennsylvanian and Permian periods, the Smoky Hills were formed from later deposits in the Cretaceous Period.

The Smoky Hills change from east to west. The eastern hills are capped with sandstone. This means the top layer of rock is sandstone with other layers, or beds, of rock underneath. The sandstone was formed from sediment carried by rivers into the shallow seas from the east.

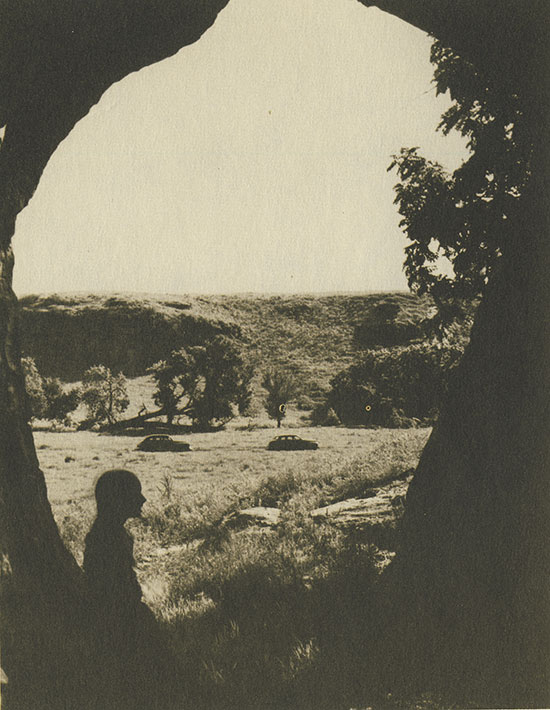

Figure 37. A view out of Palmer's Cave in Ellsworth County reveals sandstone outcrops in the Smoky Hills (photo courtesy of the Kansas Historical Society).

The hills in the middle are capped with limestone. This area of the Smoky Hills is known as post-rock country. Because wood was scarce, early farmers quarried limestone to use as fence posts. Although most of the newer posts are made of steel or wood, limestone fence posts can still be seen along many roads in the area. Limestone and sandstone in the Smoky Hills also are used for building.

Limestone in the Smoky Hills was formed from deposits in fairly shallow areas of the Cretaceous sea. Fossils of seashells and even sharks' teeth are frequently found in this area.

When the seas dried up in the western part of the Smoky Hills region, thick layers of sediment were left behind. The sediment was later buried between 1,000 and 2,000 feet underground and formed into chalk. Some areas of the chalk bed were later exposed by erosion. Today, much of the chalk at the surface has been eroded away by water. In some areas, tall, steep-sided chalk formations were left standing after the surrounding chalk eroded away. In Gove County, the Smoky Hill River carved out a large formation called Castle Rock and a series of formations called Monument Rocks. Chalk bluffs also can be found along the Smoky Hill River in Logan, Trego, and Gove counties.

Figure 38. This opening in Monument Rocks was formed over millions of years by erosion.

Chalk, like the post-rock limestone, contains marine fossils. Clams, small plants, sharks' teeth, and seashell fossils are fairly common. Fossils of large fish, giant swimming and flying reptiles, and swimming birds also have been found, but they are much rarer.

Early Permian seas helped shape the Flint Hills, the Osage Cuestas, and the Chautauqua Hills in eastern Kansas. Later Permian seas in central and western Kansas left behind thick layers of salt, which was buried by other sediment and remained hidden for millions of years until it was accidentally discovered in 1887 by drillers looking for oil and gas near Hutchinson. This salt turned out to be part of a large bed that underlies much of central and western Kansas. Today, salt mining is a major industry in Reno, Rice, and Ellsworth counties.

Figure 39. Much of the land in the Wellington-McPherson Lowlands is flat, making it good farmland. This view is towards Lindsborg.

Much of the salt is brought to the surface by miners who spend their workdays chipping, drilling, and dynamiting salt in caverns more than 600 feet underground. Most salt from underground mining is used in industry or to melt ice from roads in winter. Table salt, also mined in the area, is brought to the surface by drilling a hole deep in the ground and forcing water down it, dissolving the salt. The salt solution is then forced up to the surface where the water is evaporated, leaving the salt behind.

Because the salt contains no moisture, some of the caverns that are no longer mined are now used for storing things such as government papers and old Hollywood films. Underground salt is also dissolved to form caverns for storage of natural gas and similar products. Limestone and shale beds above and below the salt keep water out of the cavern.

The Red Hills, like the Ozark Plateau in southeastern Kansas, are probably not the image a tourist or even many Kansans would conjure up when thinking of Kansas. Though both regions are in the southern part of the state, they don't look alike. The Ozark Plateau in the southeast corner has tree-covered rolling hills. In contrast, the Red Hills in south-central Kansas don't get as much rainfall, so, except for cedars that dot the landscape, trees are sparse and the air is dry.

Figure 40. Many of the hills in the Red Hills region have unusual shapes.

Thick shales and soil in this region are red because they contain iron oxide, also known as rust. The hills, of course, got their name from their color but they just as easily could have been named Flat-top Hills because of their shape. Many of the hills in the region are flat-topped, a shape not commonly found in Kansas. Flat-topped hills known as mesas and buttes are more commonly found in the desert southwest in Arizona or New Mexico.

Sometimes hills and valleys are formed when underground rocks, rather than surface rocks, are eroded away. Big Basin and Little Basin in the Red Hills region in Clark County were formed when underground salt and gypsum deposits were dissolved by water, creating empty spaces between rock layers. The land above collapsed into the empty space, leaving a dip in the ground. Holes formed in this way are called sinkholes.

Sinkholes come in all sizes, some only a few feet across. Others are very large. Big Basin is a mile across, about 100 feet deep, and has a highway running through it. Many of Kansas' natural lakes and ponds are water-filled sinkholes. St. Jacob's Well, a pool in the bottom of Little Basin, was formed by a spring.

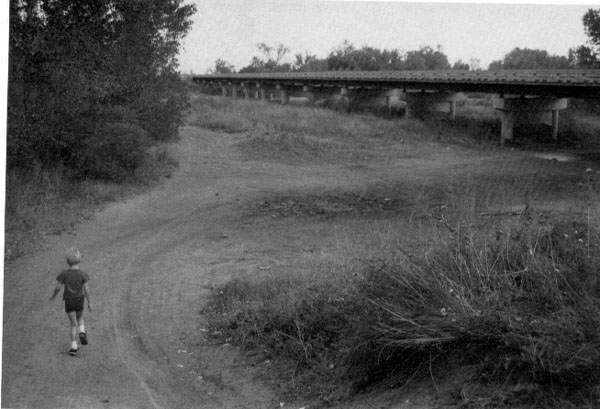

Cutting through western and central Kansas is a region carved out--or in most areas, flattened out--by the Arkansas River. The river has been pretty well tamed by the people who live along it. It doesn't flood much anymore and in some places it is dry most of the year because the water has been used faster than the rains can replace it. Some stretches in western Kansas were completely dry between 1965 and 1985. But in the past, before people settled along the Arkansas, the river frequently flooded and meandered, forming a flat area, called a floodplain, for several miles on either side of the river.

Figure 41. In 1872, a wagon crosses the Arkansas River near Great Bend. Although the river was shallow, it was 200 to 300 yards, or about one to two city blocks, wide. Now at this spot, it is only about 20 feet wide. (Photo courtesy of the Kansas Historical Society).

Figure 42. The Arkansas River southwest of Great Bend is nearly dry much of the year. This photograph was taken in 1986 within a few miles of the location of the 1872 photo.

The Arkansas and the Missouri (which forms the northeast border of Kansas) are the only rivers in Kansas that begin in the Rocky Mountains. So while the river has flattened out the land, it also has deposited sand and other sediment carried in from the Rockies and other points along its path. Sand dunes, created by wind and water, can be found in many places along the river.

Most of the sand hills don't change much anymore because they are covered with grass and other vegetation. However, some dunes in southwest Kansas are still active. Active dunes have little grass growing on them so they are always changing. Wind and water create new patterns in the sand and alter the shape of the hills and dunes. Although these changes usually don't happen overnight, the sand hills are more greatly affected by the environment than hills made of solid limestone or sandstone.

As you drive across Kansas from east to west you are gradually going up in elevation. Although the rise is so gradual that you don't notice it, you go up more than 3,000 feet if you start at the lowest point of 700 feet in Montgomery County and end up at the highest point of 4,039 feet in Wallace County. The highest point in Kansas is named Mount Sunflower, although it's just a small hill, not a mountain. Mount Sunflower is in a region known as the High Plains. The High Plains, an area of open expanses of flatlands and gently rolling hills, were once covered by a short-grass prairie. Now, much of the land has been farmed and only small areas of prairie remain.

This region was once crossed by many rivers. When the Rocky Mountains were forming millions of years ago, sediment such as sand and gravel was carried in by the rivers from the mountains. Some of the loose sand and gravel was naturally cemented to form a porous and permeable rock called mortarbed. Porous means it contains holes and permeable means the holes are interconnecting so that water can seep through. However, not all of the sand and gravel was compacted or cemented. Layers of tightly packed, but uncemented, sand and gravel are found in the subsurface in western Kansas. This layer of sand, gravel, and porous rock is known as the Ogallala Formation.

Most of the Ogallala Formation is underground, but in some places the porous rock crops out. Elephant Rock in Decatur County is an outcrop of the Ogallala Formation. Other good examples of Ogallala outcrops can be found in the bluff area around Scott County State Lake.

Figure 43. Elephant Rock in Decatur County was formed from an outcrop of porous rock from the Ogallala Formation.

When it rains in the High Plains, water seeps into the ground and is stored in the Ogallala Formation. Since the region doesn't get much rainfall, people in the area have to rely on this ground water for their water supply. Much of the water in eastern Kansas is taken directly from rivers, but in western Kansas it is often necessary to dig water wells. The ground water also is used by farmers to irrigate their crops.

People originally thought the water from the Ogallala Formation would last forever and pumped water out to be used by cities, industries, and crop irrigation. Geologists began monitoring wells in the area and have recorded fairly steady water-level declines in the Ogallala over the past 20 to 30 years. The sparse rain in the area hasn't replaced the water as fast as people have pumped it. Now we know that if it isn't used carefully, much of the water could be exhausted.

Next time you take a trip through Kansas, look around. At first glance, the landscape of Kansas seems simple and straightforward. There are no Rocky Mountains. The highest point in Kansas is just a small hill. There is no 5,000-foot-deep Grand Canyon. Kansas has its share of small ravines, but most are less than 100 feet deep, and none is much deeper than 300 feet.

Kansas has no geological features that attract hordes of tourists. But the changes that have taken place in Kansas over time, and the results of those changes, are still amazing.

Geologists, paleontologists, and other scientists have studied the rocks, minerals, fossils, landforms, water, and other natural resources for many years and have made many exciting discoveries. They have found evidence of ancient seas, glaciers, giant dust storms, buried hills and valleys, giant flying and swimming reptiles, dinosaurs, camels, woolly mammoths, and much more.

New discoveries continually add to our knowledge of the Earth around and beneath us. Scientists have found that the Earth is a very complex place. After years of exploration, there is still a lot to learn. Even Kansas, with its seemingly simple flat lands and gentle rolling hills, has a wealth of hidden information.

Previous Page--Fossils || Next Page--Maps, Glossary

Kansas Geological Survey

Placed on web Feb 11, 2016; originally published 1988, reprinted 1995.

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

The URL for this page is http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/Bulletins/ED4/04_regions.html