Kansas Geological Survey, Open-file Report 2007-18

by

Daniel F. Merriam and John R. Charlton

KGS Open File Report 2007-18

There is a fascination now about the trails west across the prairies to the gold fields of California, or the lure of the romantic Southwest, or homesteading on the plains. Much has been written on the subject, but little was recorded pictorially at the time on the conditions, hardships, and ordeals on the trails. The emigrants were subjected not only to the forces of nature, fire, drought, floods, wind and dust storms, tornadoes, heat, freezing weather and snow, and hordes of insects, but roaming bands of hostile Indians, bandits, and wild animals; many of these ordeals were recorded later by artists. Remnants of migration events are still visible on the ground in places in the form of trail ruts, remains of way stations, and restored forts and in museums.

The location of the trails across Kansas are well known and their history well chronicled, but only two trails are considered here: the Santa Fe Trail and the Oregon/California Trail (subsequently designated the Oregon Trail; Franzwa, 1989, 1990). The early history of the pioneers and frontier men on the trails is vague and hazy, but after the Civil War the fascination gripped the East and writers and artists were sent West to record the adventures in sketches, paintings, and even photographs. Sadly, many of the recordings were depressing and many of the happenings were outright disastrous. Depictions, however, are mostly of life on the frontier and of the emigrants and their problems.

After the Civil War, Kansas was being settled by hearty pioneers, but the life was still harsh. Taft (1953, p. 106) reports the following ditty by homesteaders living in dugouts.

The land of the bedbug, grasshopper and flea

I'll sing of its praises, I'll tell of its fame

While starving to death on my government claim.

This summarized life in the new land vividly.

The early travelers of the trails west, understandably, did not have the time nor where-with-all to produce art work on their trek across the prairies of Kansas. Later, however, some artists intrigued by the account of this mass migration followed in the footsteps of these hardy pioneers and recorded the arduous story in their art. Many of these recordings are in the form of emigrants wagon trains, natural land features such as springs and river crossings, or activities of the local native Americans; unfortunately, few of these were recorded in Kansas.

Numerous famous western artists and illustrators depicted life and times on the plains, some in Kansas and others that could have been in the state. These artists include Albert Bierstadt, George Catlin, Seth Eastman, William Henry Jackson, Fredrick Remington, and Charles Russell. We have selected a number of artworks by these and other professionals and amateurs as examples to illustrate the story and suggest some ways in which geology played a part in this American epic. Some of the examples are of trail markers; that is, famous geologic landmarks along the trails.

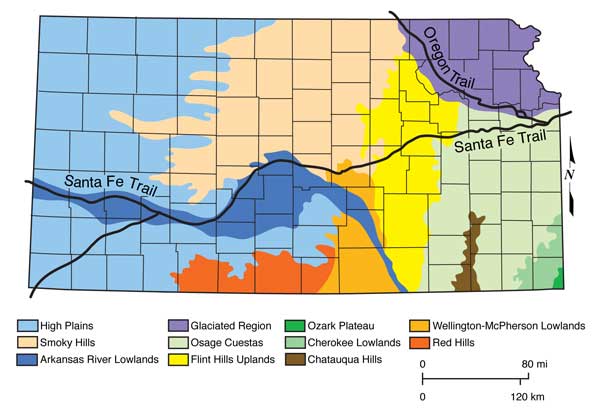

The Santa Fe Trail was in use from about 1825 to 1890, whereas the Oregon Trail was later and in a shorter time frame from 1841 to about 1869. Both trails started in Westport, now Kansas City, Missouri, and divided just west of present-day Gardner (Fig. 1). The Santa Fe Trail went diagonally across Kansas for some 450 miles crossing most of the major physiographic provinces in the state (Fig. 2). The Santa Fe continued on west and southwest to the southwestern corner of the state near Point of Rocks (the dry route) and on into the Oklahoma or continued west along the Arkansas River (the wet route) to Bent's Fort in Colorado in the shadow of the Rocky Mountains (Fig. 3). If the train chose the dry route, the trail crossed the Arkansas, at the Upper Cimarron crossing at Chouteau's Island near present-day Lakin in Kearny County. The Oregon Trail skirted across the northeastern corner of the state from Westport, Missouri, to Gardner, Kansas, and then northwestward toward Fairbury, Nebraska, to the Platte River and on west.

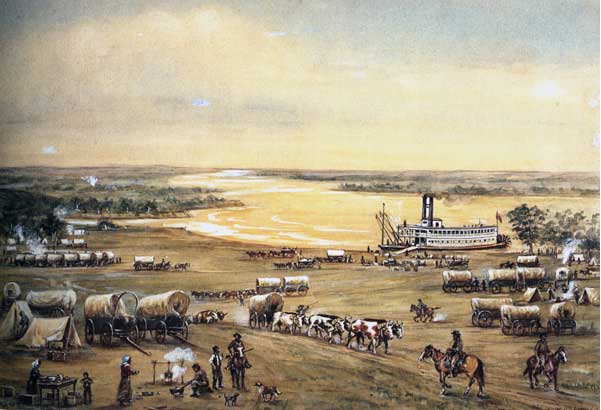

Figure 1--W.H. Jackson's rendition of Westport Landing signed and dated 1937 (Knudsen, 1997). At this stage of his life, Jackson was 94 years old. William Henry Jackson (1843-1942), worked in the West for the U.S. Geological Survey from about 1866 to 1878. An artist from New York, he was better known for his photography. He followed the Oregon Trail in 1866-1867 and later went on the Hayden Survey to the Yellowstone (Knudsen, 1997). During the Civil War he served with the Union Army and afterwards in his later years, he painted watercolors of his adventures in the West. Two of the watercolors are reproduced here (1) of the Westport Landing in Kansas City (Fig. 1) and (2) Alcove Springs in Marshall County (Fig. 19).

Figure 2--Generalized physiographic map of Kansas with route of Santa Fe and Oregon trails (Kansas Geological Survey).

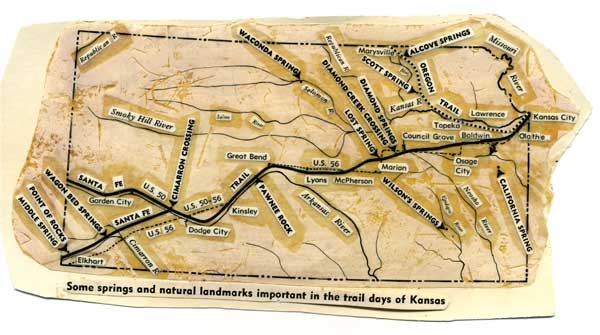

Figure 3--Some natural springs and geologic landmarks important along the Santa Fe and Oregon trails in Kansas (original drawing by Grace Muilenburg).

The routes generally followed animal or native American trails where possible. Thus, they took to the high ground so they could see what was coming, and the trek was made easier on firm, dry ground. The trails usually paralleled major rivers so that water and firewood were readily available. Known springs provided good campgrounds with an abundant supply of water, firewood, and some food for both the emigrants and animals alike. Overland treks between major river divides were more dangerous and exhausting.

As the trails became worn by use, they grew in size, that is in width, and many cutoffs and shortcuts were devised as needed or circumstances required. The most used one was the Cimarron Cutoff (in Gray County) which was a dry run but shorter and thus quicker than taking the wet route the long way through eastern Colorado to Bent's Fort and then south to Santa Fe. Because the wagon trains only made about 15 miles per day, the trip was arduous and many lost their lives along the way. The rewards, for those who made it, however, were ample and worth the effort.

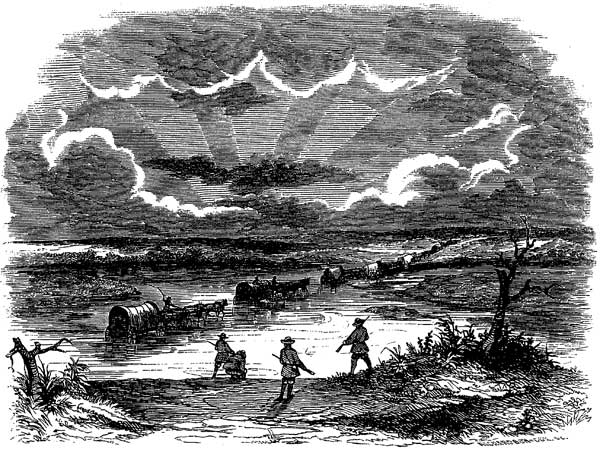

Mode of transportation in the early days before advent of the iron horse was by walking, horseback, or wagon. Hardships abounded in the westward trek as depicted by Paul Frenzeny's (1840-1902) etching of a Supply Train on the Plains in Winter (Fig. 4). Several famous western artists were attracted to the West including Russell, Bierstadt, Colman, Remington, and, of course, Frenzeny.

Figure 4--Paul Frenzeny's Supply Train on the Plains in Winter (from Harper's Weekly, 1882).

Charles Russell was fascinated by horses and wanted his epitaph to read, 'He Knew The Horse,' and he did. Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902), born in Germany and brought to America as an infant, painted The Oregon Trail in 1869. The scene is farther west than Kansas (there are mountains in the background), but shows the wagons and accompanying horsemen and herds of animals. Samuel Colman (1832-1920) also gave a rendition in oil of a wagon train in An Emigrant Train Fording Medicine Bow Creek, Rocky Mountains in 1870. Fredrick Remington (1861-1909) was a bit more imaginative in 1904 with his The Emigrants. Remington shows the wagon crossing a creek and being attacked by a band of marauding Indians. Fredrick Remington (1861-1909), born in Canton, New York, and a graduate of the Yale Art School, was related to the Indian portrayer, George Catlin. Remington had worked as a ranch hand, served as a war correspondent during the Spanish/American War, and lived in Kansas for a year in 1883 on a small ranch in northwestern Butler County. In this sense, Remington can be considered a Kansas artist. He also sold his sketches of the West to Harper's Weekly. The illustrations of a wagon train by Remington and Frenzeny, although not identified as to locale, could be in Kansas.

Several artists were intrigued by the Indians and their culture. One of the outstanding examples of an artist who recorded their lives was George Catlin (1796-1872). Apparently, although he never visited Kansas for any length of time, he did stop at Ft. Leavenworth on his way north to the upper Missouri. Seth Eastman (1808-1875), a former captain in the army, however, in 1849 painted Squaws Playing Ball on the Prairie, a setting that could have been on the high plains of western Kansas.

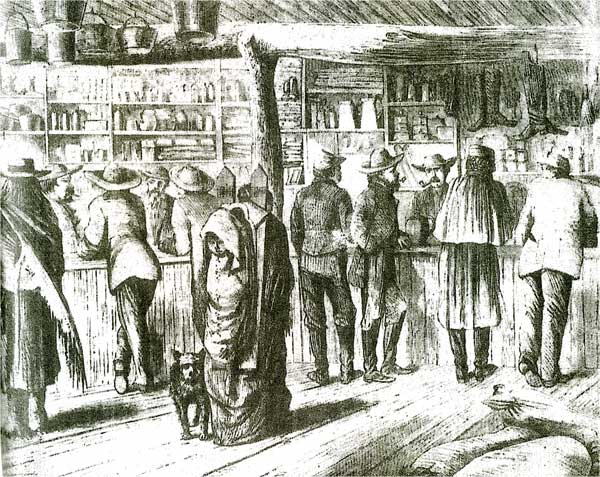

Theodore R. Davis (1840-1894) was a traveling correspondent during the Civil War chronicling many of the conflicts. After the war, Davis was commissioned by Harper's Weekly and sent West to record activities on the plains. Traveling west along the route of the Santa Fe Trail he witnessed several Indian/Army skirmishes. Supply stores, stage stations, or trading posts sprung up along the trails, and one of Davis' sketches was of the interior of Sutler's Store at Fort Dodge, Kansas, near Fort Larned. Several other illustrations in Kansas were made by Davis in the summer of 1867. He was appalled by the slaughter of buffalo and depicted his observations in Slaughter of Buffaloes on the Plains.

Paul Frenzeny and Jules Tavernier (1844-1889) were two Frenchmen also commissioned by Harper's Weekly in 1873 to make an expedition to the American West and record their findings in sketches reproduced in a series of etching for the magazine. These pictorials chronicled the life and times of the West. Part of the experience was in Kansas, especially along the Santa Fe Trail, which by this time could be followed in relative comfort aboard an iron-horse train. The two spent time in Wichita and followed the Santa Fe Trail from Emporia west to Colorado. They were particularly impressed by the hardships of the emigrants, depicted in A Prairie Wind-Storm and Fighting the Fire, probably made near Emporia (Taft, 1953). The artists were overwhelmed by the destruction of animals by hunters and recorded this slaughter in some of their illustrations.

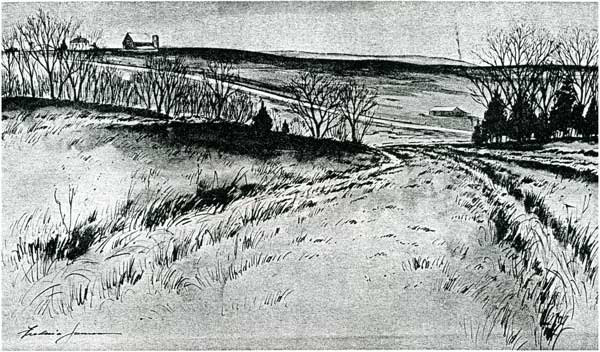

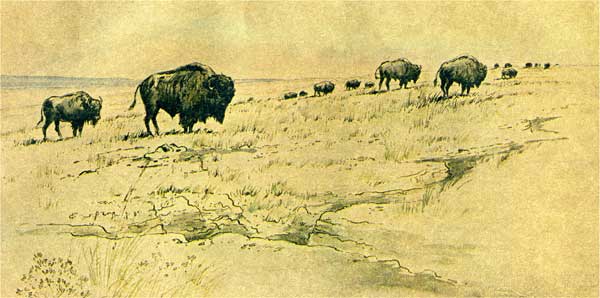

Frederic James (1916- ), a native Kansas City artist, member of the American Watercolor Society, and a former teacher at the Kansas City Art Institute, retraced and sketched scenes along the trail in 1973 for the Kansas City Star. Just west of the Oregon Trail turnoff, ruts of the trail are visible near Black Jack Park between Edgerton and Baldwin (Fig. 5). In addition, he rendered sketches of Diamond Spring (Fig. 6), Kansas, and a herd of buffalo on the Kansas prairie (Fig. 7).

Figure 5--Preserved ruts on the Santa Fe trail in the Black Jack State Park between Edgerton and Baldwin, Kansas by Frederic James in 1973. From the Sunday Magazine of the Kansas City Star, 5 May 1974.

Figure 6-Diamond Springs, southwest of Wilsey, Kansas a watercolor by Frederic James (1973). From the Sunday Magazine of the Kansas City Star, 5 May 1974.

Figure 7--Herd of buffalo on the Maxwell State Game Preserve north of McPherson, Kansas by Frederic James (1973). From the Sunday Magazine of the Kansas City Star, 5 May 1974.

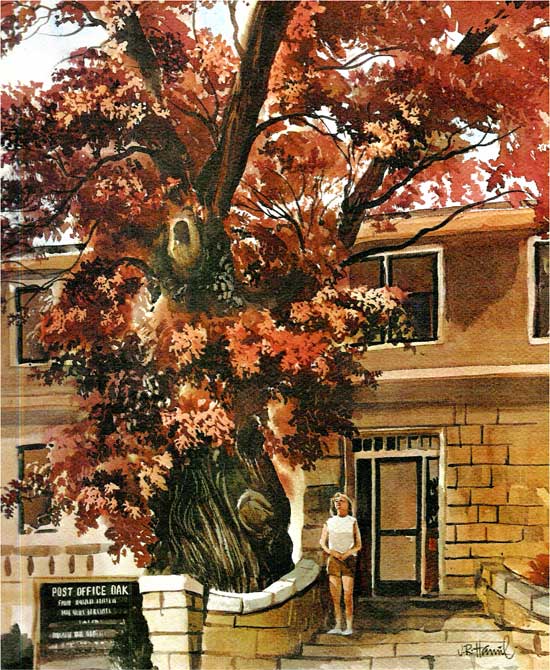

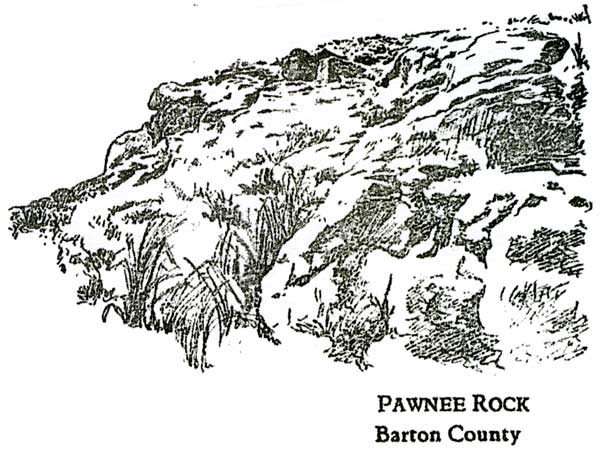

Three of the more recognized points of interest on the Santa Fe are the Post Office Oak at Council Grove, Pawnee Rock in Barton County, and Point of Rocks in extreme southwestern Kansas in Morton County. Nebraska artist J.R. Hamil (1936- ), a graduate of the University of Kansas School of Fine Arts, captured the essence of the tree that served as a mail drop on the trail in his watercolor (Fig. 8; Hamil and Hamil, 1984). Margaret Whittemore (1857-1951) from Topeka sketched Pawnee Rock in Barton County, a camping spot where the young Kit Carson shot his mule one night by mistake while a member of a party on one of his treks west (Fig. 9; Whittemore, 1937). T.R. Davis (1867) sketched the interior of an Indian trading post at Fort Dodge (Fig. 10).

Figure 8--Council Grove Post Office Oak (a watercolor by J.R. Hamil in Hamil and Hamil, 1984). Hamil is currently a resident of Kansas City.

Figure 9--Sketch of Pawnee Rock (Cretaceous Dakota sandstone), a prominent landmark on the Santa Fe trail, 1936, by Margaret Whittemore.

Figure 10--Sutler's store at Fort Dodge, 1867, by T.R. Davis (from Harper's Weekly, 25 May 1867).

Frenzeny is shown in one of his artistic renditions painting in the field with an audience of curious Indians. The scene could well be in western Kansas with the chalk bluff's in the background (Fig. 11). The High Plains is shown by George Catlin in 1834 (Fig. 12). On the sea of see-forever flatland is his representation of the western Kansas country. On the flatlands with no vegetation is a good place to see evidence of the trail (ruts) and an air view near Dodge City shows how wide the trail was in places (Fig. 13).

Figure 11--The Big Medicine Man by Paul Frenzeny

Figure 12--A see-forever view of the High Plains (an oil on board) by George Catlin in 1834 (Armstrong, 2001). A Pennsylvanian by birth, he migrated westward and was captivated by the Indians and their culture. He became one of the best known portrayers of native life on the plains.

Figure 13--Areal view of Santa Fe ruts crossing the old Soule irrigation canal west of Dodge City (Zornow, 1957, p. 84, plus Kansas Industrial Development Commission).

On west S.C. Richardson-Cox showed wagon train crossing the Arkansas River (Fig. 14). Lavender (1995, p. 9) related'...The river valley was broad and sandy. Here and there they saw cottonwood trees close to the river. Scattered thickets of wild plums grew on sand dunes father away from the river's crooked course. Soon they encountered weird-looking yucca...' Charles Russell (1864-1926), a native of St. Louis, Missouri, artist, illustrator, and sculptor, offered his pen and ink sketch of Indians Meet First Wagon Train West of Mississippi (Fig. 15; Renner, 1974).

Figure 14--A wagon train carrying merchandise to New Mexico fords the Arkansas River (an etching by S.C. Richardson-Cox reproduced by David Lavendar, 1995).

Figure 15--Charles Russell's pen and ink sketch of the Indians meeting the first wagon train on the plains (Renner, 1974). The meeting seemingly at the time was amiable and curious for both.

The 2,000-mile-plus Oregon Trail split from the Santa Fe Trail a short distance after leaving Westport, and proceeded northward toward Lawrence. The trail skirted Blue Mound just southeast of Lawrence and crossed the Wakarusa River near Eudora. An essentially unknown artist, Henry Learned (1842-1895), following his service in the Union Army during the Civil War, moved to Kansas and in 1873 produced his oil painting of the crossing (Fig. 16). The trail continued on across Mount Oread, home of the University of Kansas (Fig. 17) in Lawrence, towards Topeka. The trail stayed on the south side of the Kaw to a crossing between Big Springs and Topeka (Fig. 18) and then followed the north side of the river northwestward, continued across country crossing the Black Vermillion River to Alcove Spring on the Big Blue River in Marshall County (Fig. 19). The trail crossed the Big Blue River at Independence Crossing and continued on northwestward paralleling the Little Blue River to its headwaters, and then to the Platte River in Nebraska and west. Most of the trail in the Kansas followed the southern margin of the glaciated region.

Figure 16--The Oregon Trail's Blue Jacket Crossing of the Wakarusa River near Eudora, Kansas by Henry Learned (1844-1895); oil painting dated 1873 (Courtesy KU Spencer Museum of Art).

Figure 17--Depiction by Robert Sudlow of Oregon/California Trail crossing Mount Oread, home of the University of Kansas (Charlton, 2002). Tiny solitary horseman (extreme right) stands near the brow of the hill where University Hall was later built; three horseman are grouped on future KU campus site of Frasier Hall. The trail is prominently shown going up the south side of Mount Oread (the Oread Limestone escarpment) past the Chancellor's residence to be, then west past where Lindley Hall (home at the time of the Department of Geology and Kansas Geological Survey) was built a century later (from Taft, 1941).

Figure 18--Kansas (Kaw) River from Lecompton. The river was crossed from anywhere from here to Topeka depending on local conditions (oil painting by Louis Copt, a noted regional artist from Lawrence).

Figure 19--Alcove Springs by W.H. Jackson (Knudsen, 1997). Signed but not dated.

Those art works produced at or in river valleys generally show flat river bottoms with bank-full rivers. There were no dams or other man-made works to impound the flow of water, thus the rivers were often at or near flood stage especially in the spring. Where the water was deep, the stock swam across the river and the wagons were floated across on rafts, if the water was low, the stream or river was forded. If the weather was wet, the trail was muddy; if the trail was dry, it was dusty. Depending on whether the wagons were on firm bedrock or softer alluvium, would determine how muddy or how dusty.

Both trails started at Westport Landing in present-day Kansas City where emigrants had either arrived on river boats or had come overland from central Missouri. The wagons were unloaded from the river boats in the bottoms on alluvium to prepare for their trek west. The shallow rivers and creeks had to be forded and this was at a time when they were most vulnerable. The wagons usually were pulled by horses, mules, or oxen and often through inclement weather.

The wagons could and did leave deep ruts in swatches miles wide in the soft ground. Along the way were noted markers, such as the Post Oak Post Office, Diamond and Lost springs, Pawnee Rock, and Point of Rocks on the Santa Fe Trail. Camping sites were especially welcome at springs, and later, stores and army posts were spaced along the trail. Once the Osage Cuestas (Pennsylvanian-aged rocks) in eastern Kansas and the Flint Hills (rocks of Permian age) in the central part of the state were crossed, the trains came to the High Plains (mostly flat-lying Tertiary sediments). In the early day the plains were covered with buffalo (bison), but the white man soon put an end to that sight.

The route of the Oregon Trail across northeastern Kansas to Nebraska was short from the Santa Fe Junction. The first major river crossing was the Wakarusa River and then the Kaw River in several places from Lecompton west to Topeka and on north to the Platte River in Nebraska. Alcove Spring in Marshall County was described by the emigrants and an ideal stopping point (as were all springs). The springs and waterfall were formed by a hard resistant limestone, probably the Wreford Limestone of Early Permian age, overlying a soft shale. Crossing the Big Blue River at Independence Crossing was the last major obstacle before the Platte River valley.

The favorite subjects of the artists and illustrators of the trails west were the wagon trains and their bouts with the weather and the locals; camping spots, such as at the springs; and the usually dangerous river crossings. Some recorded the American Indian and their culture. Most of the records were made after the fact; that is, by those who came along later and had the time and facilities to paint, draw, or photograph the scenes. One exception was George Catlin who actually lived among the Indians and recorded activities on the spot. A limited pictorial history of Kansas geology was made by numerous artists and illustrators in their work. Unfortunately, the lure of New Mexico, Oregon, and California outweighed the wide-open plains country and many of the permanent artistic records were made in the more spectacular scenic country of the Southwest, Rocky Mountains, and Far West.

Armstrong, T., 2001, An American odyssey: The Monacelli Press, New York, 224 p.

Baigell, M., 1984, A concise history of American painting and sculpture: Harper & Row Publ., New York, 420 p.

Brown, M.W., 1977, American art to 1900: Harry N. Abrams Publ., New York, 631 p.

Charlton, J.R., 2002, Across the years on Mount Oread and around the Kaw and Wakarusa River valleys: Kansas Acad. Science Trans., v. 105, nos. 1-2, p. 1-17.

Craven, W., 2003, American art history and culture (rev. ed.): McGraw Hill Higher Education, Boston, 687 p.

Dorra, H., 1961, The American muse: The Viking Press, New York, 163 p.

Franzwa, G.M., 1989, Maps of the Santa Fe Trail: The Patrice Press, St. Louis, Missouri, 196 p.

Franzwa, G.M., 1990, Maps of the Oregon Trail: The Patrice Press, St. Louis, Missouri, 292 p.

Hamil, J.R., and Hamil, S., 1984, Return to Kansas: Southwind Press, Kansas City, Missouri, 105 p.

Knudsen, D., 1997, An eye for history, the paintings of William Henry Jackson: U.S. Govt. Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 89 p.

Lavender, D., 1995, The Santa Fe Trail: Holiday House, New York, 64 p.

Merriam, D.F., Hambleton, W.W., and Charlton, J.R., 2005, Kansas artistic geologists and illustrators: Kansas Geol. Survey, Open-file Rept. 2005-33, 18 p. [available online].

Merriam, D.F., Charlton, J.R., and Hambleton, W.W., 2006, Kansas geology as landscape art: Interpretation of geology from artistic works: Kansas Geol. Survey, Open-file Rept. 2006-11. [available online].

Renner, F.G., 1974, Charles M. Russell, paintings, drawings, and sculptures in the Amon Carter Museusm: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, 296 p.

Taft, R., 1953, Artists and illustrators of the Old West, 1850-1900: Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 400 p.

Whittemore, M., 1937, Sketchbook of Kansas landmarks (2nd ed.): The College Press, Topeka, 125 p. Zornow, W.F., 1957, Kansas, a history of the Jayhawk state: Univ. Oklahoma Press, Norman, 417 p.

Kansas Geological Survey, Geology

Updated Aug. 17, 2007

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

URL http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/OFR/2007/OFR07_18/index.html