Kansas Geological Survey, Bulletin 38, pt. 11, originally published in 1941

Originally published in 1941 as part of Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin 38, pt. 11. This is, in general, the original text as published. The information has not been updated.

The Marmaton group consists of about 250 feet of limestone, shale, sandstone, and coal which, together with the underlying Cherokee shale, comprise the Des Moines series of Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian) age in the northern Mid-continent area. The outcrop area of Marmaton rocks extends from southern Iowa across Missouri and southeastern Kansas into northeastern Oklahoma. Marmaton rocks seem to rest conformably on the Cherokee shale, but are separated from the overlying rocks of the Missouri series by a regional disconformity.

Marmaton rocks have long been subdivided into limestone formations and shale formations, and these have been given formal names. A few of the members of the limestone formations have been named, but the classification thus far has been decidedly incomplete. This paper introduces names for several limestone and shale units within the limestone formations and hence offers a more nearly complete classification applicable to the group in Kansas and at least in part in other states. Names are given to members of the Fort Scott, Pawnee, Altamont, and Lenapah limestone formations, and names are suggested for sandstones (probably better termed sandy facies) in the Bandera and Nowata shales.

Although the lithology of Marmaton rocks is not described here in detail, some descriptions of lateral and vertical changes are nevertheless included. The fact that there is plain evidence of cyclic sedimentation is noted. It is explained that the rocks of the Marmaton group are readily divisible into megacyclothems and cyclothems,

Purpose of the study--This paper names and defines members within the limestone formations of the Marmaton group, the upper main division of the Des Moines series. The Des Moines series is the lowermost Pennsylvanian time-rock unit exposed at the surface in Kansas. The lower part of the series, extending downward from the base of the Marmaton beds, is called the Cherokee shale. The Marmaton group comprises the following formations, named in order from oldest to youngest: Fort Scott limestone, Labette shale, Pawnee limestone, Bandera shale, Altamont limestone, Nowata shale, Lenapah limestone, and Memorial shale.

Excepting the Memorial shale (Dott, 1936) the formations were all named long ago but were only loosely defined. Definite type exposures were designated for few of them. Hence, I am proposing definite type exposures for all such formations. It has not been generally known that other limestone formations, as well as the Fort Scott limestone, are also divisible into members as are the limestone formations higher in the Pennsylvanian section of Kansas and neighboring states. This situation has led to considerable confusion in study of both the subsurface and the outcrop, especially in Missouri, where some of the separating shales are somewhat thicker than in Kansas. That the Altamont limestone in Kansas consists of two very distinct limestone members, has not been generally recognized. This probably is due to the fact that in Linn and Bourbon counties the upper member, the Worland limestone, is more conspicuous whereas in Neosho and Labette counties the lower member, the Tina limestone, is thicker and more noticeable. Similar statements apply to the Pawnee and Lenapah limestones.

No other place in North America is known to contain a more nearly complete succession of marine and non-marine rocks of late Des Moines age than that in southeastern Kansas. Hence these rocks offer excellent opportunities for many types of scientific investigations that are based on stratigraphy. The beds are moderately fossiliferous. Marine invertebrate fossils are plentiful in the limestones and thinner shale units; fossil land plants are fairly abundant in the sandy shales and sandstones that lie between the limestones, and fragments of vertebrate animal bones are abundant in at least one stratigraphic zone, the Lake Neosho shale member in the Altamont limestone,

The beds of the Marmaton group are obviously divisible into megacyclothems (Moore, 1936, pp. 21-38). Each megacyclothem begins with non-marine deposits. These are succeeded by four marine limestones, which are separated by shales that are believed to be only partly marine. Each of these thinner shale units contains, in the middle part, either black shale or black shale, coal, and underclay. Each megacyclothem ends with non-marine deposits. In general, the limestone formations comprise the cyclothems (Wanless and Weller, 1932, p. 1003) that represent widespread marine invasions, and the shale (and sandstone) formations include several cyclothems that are dominantly non-marine. Seemingly minor and local marine invasions are recorded in the shale formations. Hence each Marmaton megacyclothem seems to present evidence of four distinct marine invasions of a large area. Students of cyclic deposits will note that in southeastern Kansas these beds must have been deposited under conditions characterized by fluctuations from a position below to one at about sea level. These fluctuations were more frequent than those that occurred during the deposition of other Pennsylvanian rocks in the Mid-continent region, at least where these rocks are now exposed.

All stratigraphic information is of economic importance. The Marmaton beds are exposed in an area of shallow gas and oil production, and oil and gas is produced from them in several eastern Kansas fields. Coal beds in the Marmaton rocks are mined in Linn and Bourbon counties, and in western Missouri. Cement is being manufactured at Fort Scott from the Fort Scott limestone, which lies at the base of the group. Several of the sandstones are important aquifers. Asphalt rock is mined from Marmaton beds in western Missouri, a short distance east of the Kansas line (Jewett, 1940). The limestones are being quarried extensively for use as road metal and for agricultural "lime." Several of the beds are suitable for the production of building stone. Sandstone in the Bandera shale has been exploited in Bourbon County for unique and beautiful flagstone, which has been used in Kansas and several other states. For many years small amounts of lead and zinc ore have been mined intermittently from Marmaton rocks in Linn County. All operations that involve penetration below the soil are facilitated by stratigraphic information, and in most of them knowledge of details of stratigraphy are essential for successful operation. It is difficult to disseminate such information unless there are names for the rock units. Stratigraphy is being widely studied in connection with the planning and construction of dams.

With these facts in mind, I offer no apologies for adding a few more names to the list of stratigraphic terms applied to Pennsylvanian rocks in the Mid-continent region. Precise description of the characters and distribution of these definite rock units makes names for them needful.

This paper does not describe the Marmaton rocks in detail inasmuch as that will be treated in a later report. The present study is concerned chiefly with the classification of the strata comprising the Marmaton group.

Previous work--The evolution of stratigraphic studies of these rocks has been reviewed adequately by Moore (1936, pp. 57-67). His report gives references to the works of authors of stratigraphic names that have previously been used for Marmaton units in Kansas.

Field work--I have studied the Marmaton beds during parts of several field seasons, especially during the summers of 1939 and 1940. In the autumn of 1940, I spent several days in Missouri studying outcrops of these rocks in an area between Bourbon County and the south Missouri river bluffs in Lafayette County, Missouri. I was able to identify Marmaton units of Kansas in all the Missouri exposures that I visited, and I learned much concerning lateral changes. During a field conference in northern Missouri in the spring of 1940 with R. C. Moore, Frank C. Greene, and L. M. Cline, I studied several exposures of Marmaton beds between Lexington, Missouri (on Missouri river) and Appanoose County, Iowa. In northern Missouri, also, most members of the limestone formations are readily identifiable with those in Kansas. In July, 19411 studied Marmaton rocks in northeastern Oklahoma where Malcolm C. Oaks accompanied me in the field for a part of the time. There I was able to identify most of the members of the limestone formations as described in Kansas, but some problems of correlation, discussed in other parts of this paper, are yet to be solved.

In assigning new names to stratigraphic units in the Marmaton group, I have been guided by the criterion of usefulness and hence have given names to rocks that are important in surface and subsurface studies. The classification presented here is more or less incomplete. It includes terms that have been defined by several people. If stratigraphic units such as those in the Marmaton group could all be named and defined by one person, after the details were fairly well known, the result doubtlessly would be different from this. It will be noted that several of the units that are here called members have previously been defined in areas where the strata are somewhat different than they are in southeastern Kansas. For example, in northern Missouri and southern Iowa, the Tina limestone seems to be the lowest unit in the Altamont formation, but in southeastern Kansas other limestone beds that clearly belong to the Altamont formation occur below the type Tina. I have included them under the name Tina rather than introduce new names which would have only local application. In the case of the Lenapah formation, I have applied the name Norfleet limestone to all the limestone beds in the lower part of the formation and below a more persistent, easily recognized shale. In the Pawnee formation a black shale containing a thin persistent limestone at its base underlies the unit that in Kansas was called "lower Pawnee" but is now named Myrick Station limestone (Cline, 1941, p. 37). These strata are present over a wide region, including the type area of the Myrick Station. They clearly are a part of the Pawnee limestone, but they were not included in the strictly defined Myrick Station limestone, although they are present in its type section. Therefore, I am of the opinion that it is necessary to introduce a fourth name for the basal member of the Pawnee limestone. It is here designated the Anna member and includes a coal that is probably equivalent to the Lexington coal of Missouri.

In northeastern Oklahoma, in Nowata County, in T. 26 N., Rs. 16 and 17 E., there are two or more limestone beds below the black shale that to the north comprises the principal part of the Anna shale. In that area the limestone that I am including in the basal part of the Anna shale is three feet or more thick; about two feet below it is another limestone that is locally three feet thick. These strata are plainly a part of the Pawnee limestone assemblage and are rightly included in the Pawnee formation. Locally, as in sec. 6. T. 26 N., R. 17 E., a third limestone below the Myrick Station limestone may be properly included in the Pawnee formation. Hence it seems that in Oklahoma it would be expedient to have more names for Pawnee members. It is well to mention here that detailed stratigraphic studies may reveal that the few feet of black shale included in the upper part of the Oologah limestone in Rogers and Tulsa counties, Oklahoma, is the Anna shale. Evidence leading to the belief includes the known persistency of the Anna shale and the similarity between complete Pawnee and Oologah limestone sections.

We are now learning that the application of our present knowledge of cyclic deposition of beds is helpful in systematic stratigraphy, but many names were applied before Anything was known about cyclothems. Even recently formations have been defined seemingly without consideration of available knowledge of cyclic deposition. It is clear that all cyclothems and phases of cyclothems are not uniformly developed in the outcrop areas, and it is therefore not practical to be guided entirely by details of the cyclothems in defining formations or members. To do so would not produce the most useful kind of classification.

It is here contended that good type exposures are more important than names. There may be some workers who would question whether or not a farm name is a "geographic name", but experience has shown that names of many small towns are not much more lasting than are names of farms, and so it seems obvious that to give an exact coordinate location of an outcrop of strata to which a farm name is applied in terms of section, township, and range accords with good usage. There is small chance that the legal system of land location will change, and this kind of location of a type section certainly is much better than such a vague designation as "along Pawnee creek." Unfortunately, some parts of the United States lack the convenient division of land areas into numbered sectional units. In Kansas, even in some individual counties, there are many creeks that have the same names, and the same political township names are used in many counties. In selecting new names I have first considered the location of good type exposures. As new names for members in the Lenapah limestone, I have used two farm names, Norfleet (Norfleet limestone) and Perry Farm (Perry Farm shale).

The desirability of giving names to lenticular sandstones such as occur in shale units like the Labette and Bandera is questionable. In these and many other shale formations in the Mid-continent Pennsylvanian rocks, sandstone occurs in lenses, some of which are channel fillings that seem to lie at different horizons. These sandstone lenses are important subsurface reservoirs for oil, gas, and water. Numerous subsurface names have been applied to them and names such as Englevale and Warrensburg have been given to them at the outcrops, so it seems useful to have names for such sandy zones. It should be understood, however, that these names are more general in their application than are most "member names." In this way I recognize Warrensburg sandstone as sandstone in the Labette shale, and in this paper I suggest Walter Johnson sandstone as the name to be used in the same way for sandstone in the Nowata shale. The Bandera shale was named after a sandstone quarry and former town in Bourbon County, Kansas, called Bandera. As a name for sandstone lenses in the Bandera shale, Bandera Quarry sandstone is proposed. Wayside "sand" is the most common drillers' term for sandstone which is correlative with the Walter Johnson sandstone, and Peru is a subsurface name for the Warrensburg sandstone. The names Wayside and Peru, however, have frequently been applied to sandstone facies in more than one formation.

The Marmaton group consists of about 250 feet of shale, sandstone, and limestone beds and a very minor amount of coal. The group lies conformably above the Cherokee group, which is dominantly shale, but contains a considerable amount of sandstone, and minor amounts of coal, limestone, and underclay. The presence of a persistent limestone, the Ardmore (Gordon, 1893, p. 20), lying from 80 to 100 feet below the base of the Marmaton group or top of the Cherokee shale, has led to consideration of excluding the upper part of the Cherokee group, as now classified, from that group. If this is desirable, the base of the Marmaton group probably should be placed at the base of the Ardmore limestone inasmuch as it does not seem desirable to introduce another group name for these upper Cherokee strata. It seems to me, however, that the Cherokee beds are now properly classified. Long usage in Kansas, Oklahoma, and Missouri has established the base of the Fort Scott limestone as the upper limit of the Cherokee shale. The Ardmore limestone, although persistent, does not make conspicuous outcrops, and it is not everywhere readily identifiable in single exposures. Locally in southeastern Kansas there is another equally prominent limestone a few feet below the Ardmore; in northeastern Oklahoma, in Craig and Rogers counties, there is a limestone bed nearly 5 feet thick in the Cherokee shale above the Verdigris limestone. It is commonly supposed that the Verdigris is equivalent to the Ardmore limestone. But the data at hand indicate from cyclic evidence that the higher Cherokee limestone of Oklahoma may be equivalent to the Ardmore limestone of southeast Kansas and Missouri.

In this paper the lower boundary of the Marmaton group is, in accordance with current definition, placed at the base of the Fort Scott limestone formation. The base of the Fort Scott formation is discussed in a later part of this report. In Kansas the Marmaton group lies disconformably below the Hepler sandstone (Jewett, 1940a, pp. 8-9), lowest unit in the Missouri series. Recently Moore (1936b, fig. 7, pp. 43) used the name "Warrensburg" for the Hepler sandstone and showed it in diagram above a disconformity reaching nearly as low as the lower Fort Scott limestone. I have nowhere found the base of the Hepler, as seen at outcrops or identified in wells, to occur lower than the top of the Altamont limestone. The disconformity at the top of the Des Moines series has been recognized northward from the Arbuckle Mountains and into southeastern Kansas (Moore, 1936, p. 71; Jewett, 1940a, pp. 8-9), and I have definitely recognized it for several miles into Missouri. Cline (personal communication, Oct. 16, 1940) is of the opinion that it can be recognized as far north as Putnam County, Missouri, which is on the Missouri-Iowa line, about 150 miles northeast of the place in Cass County, Missouri, to which I traced the disconformity.

Examination of the rock contacts along the post-Marmaton disconformity in parts of Kansas seems to indicate nearly continuous deposition over moderately wide areas. Locally, as in Bourbon County, beds assigned to the upper part of the Marmaton group seem to grade upward through sandy shale into the Hepler sandstone. However, to conclude that there was nearly continuous deposition there does not seem to be in accordance with regional evidence. In southeastern Oklahoma sandstone and grit at the base of the Seminole formation lie above the disconformity that marks the Des Moines-Missouri boundary (Moore, 1936, p. 71). Oaks has shown me field evidence of the fact that farther north the lowermost Seminole beds are stratigraphically higher than the "lower Seminole sandstone." This indicates either northward overlap of Missouri sediments or removal of older Missouri beds from northeastern Oklahoma before deposition of later Seminole rocks or both overlap and removal. It is clear that the Hepler sandstone is equivalent to beds in the upper part of the Seminole formation. It is probable that in Labette County, Kansas, the true Des Moines-Missouri boundary is a short distance below the base of the Hepler sandstone and that a lenticular coal bed below the base of the Hepler sandstone is rightly correlated with the Dawson coal of Oklahoma. The Dawson coal is in the Seminole formation. Deformation between late Marmaton and early Missouri deposition in this region was seemingly very slight.

In Kansas the Marmaton rocks are dominantly shale. Limestone is second in quantitative importance and sandstone is third. The thicker shale units, which are called formations, include sandstones that are classified in two general types on the basis of their relationship to the shales. One type of sandstone can be sharply differentiated from the non-arenaceous clay shale below and in lateral directions. The other type is gradational from shale through sandy shale. It should be noted that this difference is based more upon the kind of contact than upon the rock itself, although the first type is generally less clayey than is the type with gradational contacts. Clay and sand were being deposited at about the same time and some cutting and filling took place. In those outcrops where a sand-filled channel cuts clay shale one sees the first type of contact. In general channeling seems to be not more than 25 feet in depth.

At and near Warrensburg, Mo., sandstone belonging to the Labette shale formation in the lower part of the Marmaton group fills a channel (Hinds and Greene, 1915, p. 91) that locally has cut out the Fort Scott limestone. A very coarse limestone conglomerate lies at the base of the sandstone in the town of Warrensburg. Sandstone is present in the Labette shale throughout most of the outcrop area in Kansas and northeastern Oklahoma, and it is well known in the subsurface. I have seen sandstone in many exposures between Warrensburg, Mo., and eastern Kansas. Pierce and Courtier (1935, pp. 1061-1064) reported that in Crawford County, Kansas, sandstone in the Labette shale lies in a channel, the base of which locally is lower than the top of the Fort Scott limestone. At the present time this condition cannot be verified at the exposures they cited. They gave the name Englevale to this sandstone, but Warrensburg seems to be the correct name, and lenticular sandstones at approximately the same horizon in the subsurface are known as Peru sand. It is misleading, however, to imply that sandstone occurs in but one zone in the Labette shale, for in many exposures there are two or more sandstones separated by non-arenaceous shale or by shale and limestone. It is indicated here that the Warrensburg and Englevale channels lie probably at approximately the same stratigraphic position and that their fills probably represent the most widespread sand facies in the formation.

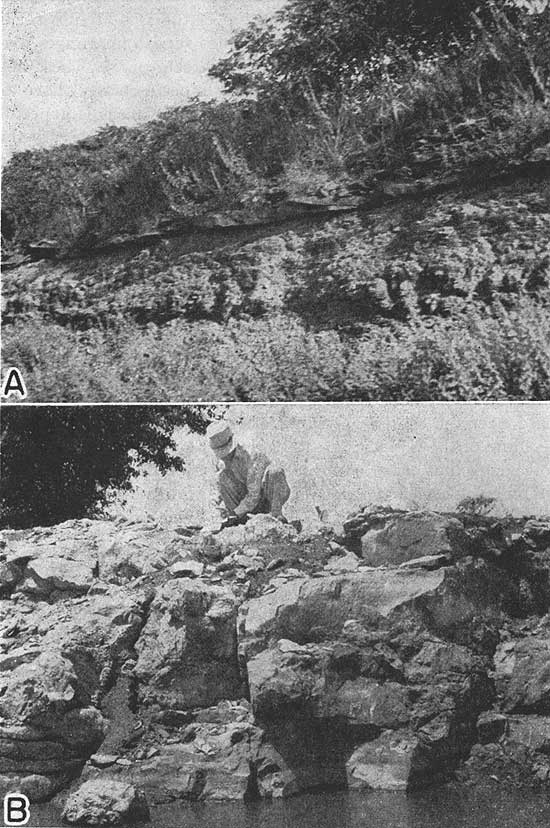

In the Marmaton group sandstones of the kind discussed above occur in the Labette shale, the Bandera shale and the Nowata shale. The disconformities or diastems at their bases may be striking in some exposures but they do not seem to represent the lapse of any appreciable amount of time. In general the sand is regularly bedded but locally it is cross-bedded. The grains of quartz sand are fine, and everywhere mica and clay are abundant in the sandstones. At several exposures in western Missouri, coarse limestone conglomerates occur next below sandstones in the Bandera and Labette shales. I have not seen such conglomerates in the Marmaton beds in Kansas. Plant fossils are plentiful. The more persistent coal beds associated with these sandy shales and sandstones lie below and above the sand bodies but the more localized coals occur within the sandstones. There is generally a few inches of underclay below the coal beds. Non-arenaceous shale in the thicker "shale" units is well bedded, generally blocky, and at the outcrops contains abundant limonite in the form of concretions and stringers. Because of the general absence of fossil marine animals, the presence of numerous coal beds, presence of cross-bedded and ripple-marked sandstones and the evidence of cutting and filling, it is my opinion that nearly all of the material in the "shale" formations was deposited above sea level. That there were local and brief invasions of sea water is indicated by the occurrence of thin, lenticular limestones, such as have been noted particularly in the Labette shale.

Shales that separate the limestone members in the "limestone" formations are partly if not wholly marine. They contain fossil brachiopods, bryozoans, crinoid remains, and locally mollusks, and corals. Black, carbonaceous shale and small amounts of coal are characteristic of some of the thinner shale units. It is very probable that the black shale was deposited almost at sea level. Where fossiliferous, the black shale contains a sparse fauna, in which brachiopods are most conspicuous, and conodonts are locally present. There are generally small dark phosphatic concretions in the black shale. The thin fossiliferous shales are thinner bedded than the thicker non-marine (?) shales. Thin coal beds in these thinner shales may have been locally deposited below sea level; brachiopod shells have been found in some of the coal beds. The limestones include a variety of lithologic types, but each type seems to have a more or less definite place within the cyclic arrangement of the rocks. The greatest amount of limestone is light in color and occurs in thin, wavy beds. It is commonly "pseudo-brecciated" or constitutes an intraformational breccia. A thin film of black, carbonaceous material is abundantly present between beds, covering the irregular bedding surfaces. Secondary crystallization is common in these thicker more pervious limestones. The description above is a general one that applies to the uppermost limestone units or the fourth one from the base of the limestone formation, although in part it applies also locally to other beds, particularly to the second one from the base. Coralline limestones, dominantly composed of Chaetetes but containing plentiful "Aulopora" and algal deposits are characteristic of the thicker limestones. The coral deposits are almost, if not quite invariably the second and fourth limestone units from the bases of the limestone formations. Fusulinids are found in the same limestone units as those that contain the abundance of corals but the fusulinids occur only where the corals are sparse or absent. A considerable amount of earthy dark gray and brown limestone which weathers a deep rusty brown occurs generally in the second limestone from the base of the assemblage. Such rock commonly contains fusulinids and brachiopods. The basal and the third limestone from the top in each assemblage is, with local exceptions, quite thin, argillaceous, and slabby. In some exposures these two units are absent or are represented only by calcareous shale or thin coquinas.

The name Marmaton is applied to strata outcropping in a narrow belt from southern Iowa, across Missouri to Linn and Bourbon counties, Kansas, and across southeastern Kansas and northeastern Oklahoma to the Arkansas river valley. In Oklahoma the Marmaton beds have not been traced individually south of the Arkansas river. Continuous beds south of the river comprise all or a part of the rocks included in the Wetumka, Wewoka, and Holdenville formations. The outcrop area of Marmaton beds is bounded on the north by outcrops of Cretaceous sediments in Iowa. J. B. Knight (1933, pp. 166-172, fig. 1-3, 5) identified the Fort Scott limestone, Labette shale, and Pawnee limestone in an outlier of Pennsylvanian beds in St. Louis County, Missouri. Knight correlated these beds with parts of the Carbondale and McLeansboro formations in Illinois. It seems evident that these deposits were originally continuous from the Mid-continent region eastward across the area of the present Mississippi valley.

The Marmaton rocks comprise the upper and more calcareous (more dominantly marine) part of the sediments of Des Moines age in the northern Mid-continent region. According to Moore (1936, pp. 53-54) the following rocks are of Des Moines age: the Deese beds in the Ardmore basin south of the Arbuckle Mountains, most of the Strawn group in north central Texas, the upper part of the Haymond formation and the lower part of the Gaptank beds in west Texas, the upper part of the Pottsville, the Allegheny and lowermost part of the Conemaugh beds in the Appalachian region, the lower part of the Minnelusa formation in the Black Hills, the McCoy formation, most of the Weber and the lower part of the Hermosa beds in Colorado, and the Magdalena limestone of New Mexico. Condra and Reed (1935, p. 45) found evidence indicating that a part of the Hartville formation in southeastern Wyoming is equivalent to the Marmaton rocks of Kansas.

Carboniferous system--Most North American geologists, in accordance with the classification found in the majority of American textbooks on historical geology, divide Paleozoic rocks younger than Devonian into three systems that are named (in upward order) Mississippian, Pennsylvanian, and Permian. The United States Geological Survey, however, designates these rocks as the Carboniferous system and divides this system into the Mississippian, the Pennsylvanian, and the Permian series. In Europe the term Carboniferous system is applied to rocks older than Devonian and younger than Permian, Although opinions may still differ as to the horizon of the Pennsylvanian-Permian boundary, the three classifications use the name Permian for rocks of the same age (Moore, 1940; Dunbar, 1940). Moore (1936, pp. 246-248) has discussed the classifications mentioned above, and has pointed out (1936, p. 248; and 1940, pp. 291 and 325) that the Carboniferous and Permian systems, as applied in Europe, are acceptable, desirable terms for the standard classification of the geologic column of North America, and that the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian may be classed as sub-systematic divisions of Carboniferous.

Pennsylvanian subsystem--Although neither Pennsylvanian nor Mississippian are represented by subdivisions of the European Carboniferous that are equal in span (Moore, 1936, p. 248), there is ample reason for keeping these names, for they apply to divisions more or less well differentiated by means of paleontology, lithology, and structure. They are useful rock names, and it seems best to classify them as subsystems because within them are smaller divisions to which the term series is best applied. In the northern Mid-continent region the Pennsylvanian subsystem contains the Des Moines, the Missouri, and the Virgil series, each of which is separated from rocks below and above by more or less pronounced regional disconformities and faunal changes.

Des Moines series--As redefined by Moore (1932, p. 89; 1936, p. 51) the Des Moines series in Kansas includes beds ranging from the base of the Cherokee shale to the widespread disconformity occurring at the base of the Bourbon group. As shown in this paper there is evidence that this hiatus can be traced far northward. In Oklahoma and Arkansas the disconformity at the top of the series is at the base of the Seminole conglomerate (Moore, 1936, pp. 52, 53, 79). In Kansas, northeastern Oklahoma, Missouri, and Iowa the Cherokee shale rests on Mississippian and older rocks, and in Arkansas and farther south in Oklahoma the base of the Atoka formation, appearing to be the base of the Des Moines series (Moore, 1936, p. 53; Newell, 1937, table 1, p. 19), rests on folded and beveled beds of the Morrow series of the Pennsylvanian subsystem (Moore, 1936, fig. 6, p. 602). According to Moore (1937a, pp. 656, 671) the hiatus between Morrow and Des Moines strata marks the occurrence of Wichita orogeny--the folding of the Wichita mountains in southern Oklahoma. Newell (1937, p. 39) has shown from his studies in Oklahoma that the Warner sandstone, 200 feet above the top of the Atoka formation, probably is equivalent to the basal part of the Cherokee shale in southeastern Kansas. If this condition obtains it is due to overlap of the Des Moines rocks from the south, and hence the Des Moines series includes, in Oklahoma, about 800 feet of beds older than the Cherokee shale as it is defined in Cherokee county in southeastern Kansas. Moore (1936, p. 18) has shown that such units as the Des Moines, bounded by important structural and paleontological breaks, are best designated as series. In Kansas the Des Moines series comprises about 600 feet of rock. The lower unit, the Cherokee shale, is principally shale and sandstone; the upper unit, the Marmaton group, is briefly described in this paper.

Definition--In 1932 and in 1936 Moore (1936, p. 57) defined the Marmaton group as including beds between the base of the Fort Scott limestone and the upper limit of the Des Moines series, which he stated to be the unconformity below the Warrensburg (Hinds and Greene, 1915, p. 91) Channel sandstone. Recent field studies in Missouri have convinced me that the Warrensburg sandstone is equivalent to a part of the Labette shale, which is in the lower middle part of the Marmaton group. The error involved, however, is merely one of the correlation of the Warrensburg sandstone. The Marmaton group is defined as including all beds between the base of the Fort Scott limestone and the upper limit of the Des Moines series. From northeastern Linn County southward to the Kansas-Oklahoma line, a disconformity is exposed below a thin sandstone which I have named Hepler (Jewett, 1940a, pp. 8-9). In Kansas, the Hepler sandstone rests disconformably on the Memorial (?) shale, the Lenapah limestone, and on a surface almost or quite as low stratigraphically as the top of the Altamont limestone.

I have collected Des Moines fossils, notably the brachiopod Mesolobus, from shale almost as high as the base of the Hepler sandstone several feet above the Lenapah limestone. The disconformity at the base of the Hepler sandstone is the first physical evidence of a break observed in Kansas above the Lenapah limestone, unless the occurrence of coal beds denotes interruption of sedimentation. Therefore it seems that these beds between the Lenapah limestone and the Hepler sandstone belong in the Des Moines series. The term "Des Moines fossils" denotes forms that have not been reported in strata higher than the top of the Des Moines series as defined here. Yet because of the apparent northward overlap of Missouri beds in Oklahoma and because of the clear evidence that the Hepler sandstone is equivalent to beds younger than lowermost Missouri beds in eastern Oklahoma, it cannot be definitely stated that the disconformity at the base of the Hepler sandstone is, even in Kansas, consistently the true Des Moines-Missouri boundary. If coal below the Hepler sandstone in Labette County, Kansas, is stratigraphically equivalent to the Dawson coal in Oklahoma, then the true boundary in Kansas is lower than the base of the Hepler sandstone.

The Marmaton group comprises, in ascending order, (1) the Fort Scott limestone, (2) Labette shale, (3) Pawnee limestone, (4) Bandera shale, (5) Altamont limestone, (6) Nowata shale, (7) Lenapah limestone, and (8) Memorial shale. The combined thickness is about 250 feet.

Type locality--The type locality has not been designed more definitely than along Marmaton river in Bourbon County, Kansas (Haworth, 1898, p. 92). In regions of low relief it may not be possible to cite a definite type exposure for a stratigraphic unit as thick as the Marmaton group. All beds in the group, however, can be seen along the river bluffs from Fort Scott westward to Uniontown in Bourbon County. Most of them can be seen along U.S. highway 54, between Fort Scott and Uniontown. A composite section along Marmaton river follows:

| Composite section of Marmaton strata in the type exposures along Marmaton river from Fort Scott to Uniontown, Bourbon County, Kansas. | Feet | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bronson group | |||||

| Hepler sandstone | |||||

| (44) Sandstone, massive | 4.0± | ||||

| Des Moines series | |||||

| Marmaton group | |||||

| Memorial (?) shale | |||||

| (43) Shale, thin beds, micaceous | 8.5 | ||||

| Lenapah limestone | |||||

| (42) Limestone, light bluish gray, granular, crinoidal and molluscan, hummocky upper surface | 1.0 | ||||

| Nowata shale | |||||

| (41) Shale, gray, limonitic in upper half | 29.0 | ||||

| Altamont limestone | |||||

| Worland limestone member | |||||

| (40) Limestone, nodular, and shale | 2.0± | ||||

| (39) Limestone, bluish gray, dense, and somewhat nodular, containing solution (?) cavities up to 1.75 x 6' filled with bedded nodular limestone and shale containing fusulinids | 2.0± | ||||

| (38) Limestone, gray, dense, and crystalline, nodular, brachiopods | 7.0 | ||||

| Lake Neosho shale member | |||||

| (37) Shale, mostly gray, black in middle part, phosphatic concretions | 1.0± | ||||

| Tina limestone member | |||||

| (36) Limestone, gray and tan, mottled, dense, wavy beds, Composita and Squamularia | 1.2 | ||||

| (35) Shale, yellow, flaky | 0.2 | ||||

| (34) Limestone, brownish gray, nodular, massive, crinoid fragments | 3.0 | ||||

| Bandera shale | |||||

| (33) Shale, yellow, gray, partly maroon | 20.0± | ||||

| (32) Sandstone, buff and gray | 22.0± | ||||

| (31) Covered | ? | ||||

| Pawnee limestone | |||||

| Laberdie limestone member | |||||

| (30) Limestone, covered | 5.5± | ||||

| (29) Limestone, gray, thin beds | 4. | ||||

| Mine Creek shale member | |||||

| (23) Shale, black, fissile to blocky | 1.5 | ||||

| (27) Limestone, dark gray, crystalline | 0.3 | ||||

| (26) Shale, gray, fissile | 0.7 | ||||

| Myrick Station limestone member | |||||

| (25) Limestone, brown, nodular | 0.8 | ||||

| (24) Limestone, nodular, gray, Chaetetes | 3.8 | ||||

| (23) Shale, gray, locally dark fissile | 0.4 | ||||

| (22) Limestone, brown, carbonaceous streak in upper part | 3.3 | ||||

| Anna shale member | |||||

| (21) Shale, gray | 0.8 | ||||

| (20) Shale, black, black concretions | 1.0± | ||||

| Labette shale | |||||

| (19) Shale, yellow gray, slightly carbonaceous | 15.2 | ||||

| (18) Shale, mostly covered, blocky | 5.4 | ||||

| (17) Shale, sandy shale, and sandstone | 5.4 | ||||

| (16) Shale, yellow | 9.0 | ||||

| (15) Coal | 0.5 | ||||

| (14) Covered interval | 2.0 | ||||

| Fort Scott limestone | |||||

| Higginsville limestone member | |||||

| (13) Limestone, light gray, brown weathering, giant crinoid stems, Chaetetes, fusulinids, and a few other fossils, massive | 5.0 | ||||

| (12) Limestone, like above in color, thinner bedded, fossils less prominent | 8.0 | ||||

| (11) Limestone, yellow to gray massive | 1.0 | ||||

| Little Osage shale member | |||||

| (10) Shale, yellow in upper part, gray in lower part | 0.9 | ||||

| (9) Houx limestone bed, brown in upper part, blue gray in lower part | 0.6 | ||||

| (8) Shale, black, mostly fissile, small black concretions | 3.7 | ||||

| (7) Shale, black, coaly | 0.3 | ||||

| (6) Coal, "Summit" | 0.7 | ||||

| (5) Shale, dark gray, fissile | 0.5 | ||||

| (4) Shale, dark, slacks into small blocks | 2.5 | ||||

| Blackjack Creek limestone member | |||||

| (3) Limestone, blue gray, massive, conchoidal fracture | 5.2 | ||||

| Cherokee shale | |||||

| (2) Shale, black, mostly flaky, not fissile, small black concretions throughout and giant, dark, hard concretions near base | 1.4 | ||||

| (1) Mulky coal | 1.4 | ||||

Locations of measured sections that are joined in making the composite section are as follows: Beds 1-13, NE sec. 19, T. 25 S., R. 25 E.; Beds 14-21, sec. 16, T. 25 S., R. 24 E.; Beds 22-30, sec. 11, T. 25 S., R. 24 E.; Bed 32, SW sec. 29, T. 25 S., R. 23 E.; Bed 33, NW sec. 29, T. 25 S., R. 23 E.; Beds 34-37, NE sec. 25, T. 25 S., R. 22 E.; Beds 38-40, SE sec. 24, T. 25 S., R. 22 E.; Bed 41, sec. 30, T. 24 S., R. 24 E.; Beds 42-44, N sec. 23, T. 25 S., R. 22 E. Exposures along U.S. Highway 54 in distances west of Ft. Scott are: Beds 3-13, 1/2 mile; Beds 22-30, 2 miles; Beds 34-36, 5.5, 7, 8, 10, and 11 miles; Beds 38-40, 11 miles.

As redefined by Bennett (1896, p. 91) and accepted by Moore (1936, p. 59), the Fort Scott limestone includes three members, two limestones and a separating shale. The lower limestone has long been called lower Fort Scott or "Cement rock" and the upper limestone is known as the upper Fort Scott. The Missouri Geological Survey has used the name "Lexington bottom rock" for the upper Fort Scott limestone.

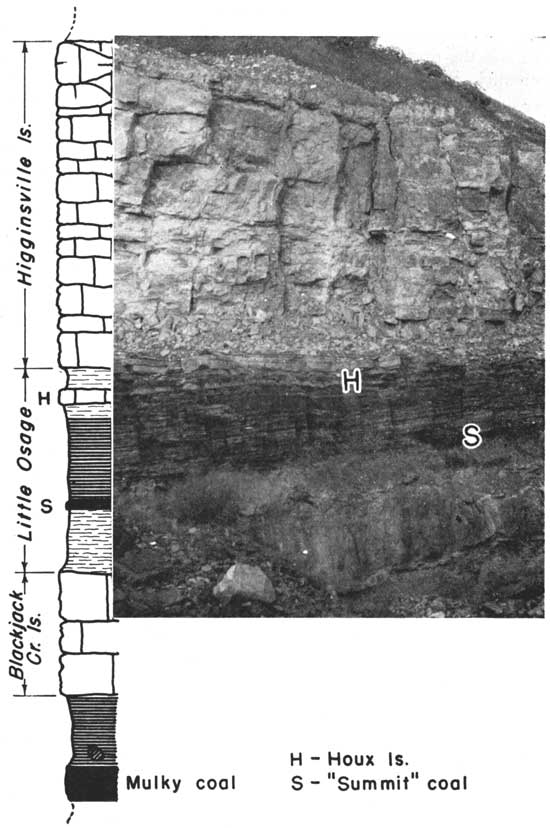

Cline (1941, p. 36) has named the lower member the Blackjack Creek, the upper, the Higginsville, and a thin limestone that occurs in the shale between them, the Houx limestone. In this paper I am proposing the name Little Osage shale for the beds that lie between the Blackjack Creek and Higginsville limestones, and I regard the Houx limestone as a bed in the little Osage shale member. A limestone that lies within the Little Osage shale in Kansas is believed to be the same as the Houx limestone at the Houx ranch in Johnson County, Missouri.

Locally in southeastern Kansas, a limestone called Breezy Hill (Pierce and Courtier, 1938, p. 33) occurs a few feet below the Blackjack Creek limestone. It seems to correspond in cyclical position to higher limestones that are included at the base of the other limestone formations of the Marmaton group. Where present this thin limestone occurs below the black shale and Mulky coal, both of which are shown as a part of the Cherokee shale in the above section. Because the "Cement rock" has for so long been regarded as the base of the Fort Scott limestone and because the black shale below it has long been used in the subsurface to mark the top of the Cherokee shale and also because the Breezy Hill limestone is very lenticular, it seems best not to amend the definition of the formation to include these beds. If it is desirable to include the Breezy Hill limestone and overlying shale in the Fort Scott formation, then the assigned limits of the Blackjack Creek member might be amended to include the Breezy Hill bed. In that event, the base of the formation would be at different horizons in different places, but such definition is deemed entirely natural and proper in view of the controlling position of lithology, rather than time span in determining formational boundaries (Moore, 1932, pp. 86-87; 1936, figs. 4A and 4B, pp. 38-40). In fact, the lower limits of the other limestone formations, as defined in this paper, as well as several other Pennsylvanian formations, are at different stratigraphic levels. For a long time oil men have used the name "Oswego" limestone instead of Fort Scott, but that name is preoccupied in geologic literature by a Silurian formation in New York. The three members of the Fort Scott formation are identifiable from southern Iowa (Cline, 1941, fig. 2, p. 27) to the southern part of Tulsa county, Oklahoma.

Outcrops at the type locality--In all probability Bennett (1896, pp. 88-91) regarded the exposure in the cut a short distance east of the Missouri Pacific Railway station in Fort Scott as the type exposure of the Fort Scott limestone. A better view of the whole formation can now be seen in the cement plant quarry in the NE sec., 19, T. 25 S., R. 25 E., northeast of Fort Scott, Kansas. This quarry is cut in the valley wall of Marmaton river and the strata will remain well exposed for a long time, even though operation of the quarry ceases. This outcrop is here considered as the type exposure. Plate 2 presents a photograph and graphic section of this type exposure. The description of the measured section follows.

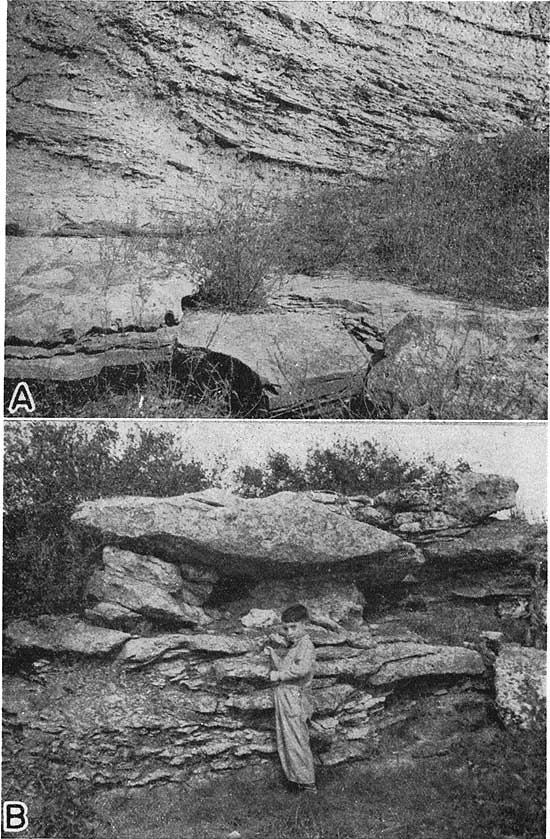

Plate 2--The type exposure of the Fort Scott limestone, cement plant quarry, northeast of Fort Scott, Bourbon County, Kansas. Note that only the lower more massive phase of the Blackjack Creek limestone is present here. See plate 4.

| Section at the type exposure of the Fort Scott limestone, NE sec. 19, T. 25 S., R. 25 E., Bourbon County, Kansas. | Feet | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fort Scott limestone (27.9 feet) | |||

| Higginsville limestone member (14 feet) | |||

| (13) Limestone, light gray, brown weathering, massive, giant crinoid stems, Chaetetes, fusulinids, and a few other fossils, massive | 5.0 | ||

| (12) Limestone, like above in color, thinner bedded, fossils less prominent | 8.0 | ||

| (11) Limestone, yellow to gray, massive | 1.0 | ||

| Little Osage shale member (7.7 feet) | |||

| (10) Shale, yellow in upper part, gray in lower part | 0.9 | ||

| (9) Houx limestone bed, brown in upper part, blue gray in lower part | 0.6 | ||

| (8) Shale, black, mostly fissile, small black phosphatic concretions | 3.7 | ||

| (7) Shale, black, coaly | 0.3 | ||

| (6) Coal, "Summit" | 0.7 | ||

| (5) Shale, dark gray, fissile | 0.5 | ||

| (4) Shale, dark, slacks into small blocks | 2.5 | ||

| Blackjack Creek limestone member | |||

| (3) Limestone, blue gray, massive, conchoidal fracture | 5.2 | ||

| Cherokee shale | |||

| (2) Shale, black, mostly flaky, not fissile, small black concretions throughout and giant, dark, hard limestone concretions near base | 3.4 | ||

| (1) Mulky coal | 1.4 | ||

The name Blackjack Creek is accepted as the name of the lowest member of the Fort Scott limestone, which has heretofore been called "lower Fort Scott" or "Cement rock." It lies above black shale, which is, according to present classification, the upper part of the Cherokee shale and which contains the Mulky coal bed. Next above the Blackjack Creek limestone is the Little Osage shale, which contains the "Summit" coal and Houx limestone.

The name Blackjack Creek was introduced by Cline (1941, p. 36). Hinds (1912, p. 220) definitely correlated the "lower Fort Scott" and the limestone exposed in what Cline (and F. C. Greene) chose as the Blackjack Creek type exposure. I have not studied the type exposure, but I have seen the "lower Fort Scott" limestone in many nearby places in Johnson County, Missouri, and have found it to be very similar to the same stratum in Bourbon County, Kansas.

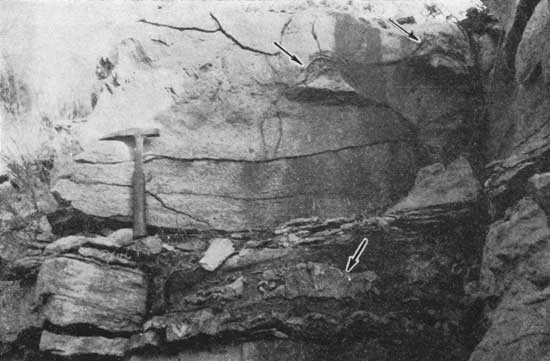

In Kansas the thickness of the Blackjack Creek ranges from about 5 feet in Bourbon County to 16 feet or more in Labette County; that is, the limestone thickens southward. It is more fully developed in the southern part of the Kansas outcrop where the upper part is principally composed of the coral Chaetetes. In Bourbon County it is massive, bluish gray, and somewhat earthy. Farther south the same description fits the lower part, but the overlying portion is a more crystalline, lighter-colored, irregularly bedded, brecciated coralline limestone. It can be identified readily along the Fort Scott outcrop across the state. The upper and lower phases of the Blackjack Creek limestone have been observed in Oklahoma, but in the vicinity where the Fort Scott members disappear in southern Tulsa county only the massive lower part is present. (See plates 2 and 4 for comparison of these two phases of the Blackjack Creek limestone.)

Type exposure--According to Cline (1941, p. 36), the type exposure of the Blackjack Creek limestone is in Johnson County, Missouri, "four miles southeast of Fayetteville and along Blackjack Creek." In "Section II" Cline (1941, p. 34) describes the member from an outcrop on the Houx ranch "about six miles west of Warrensburg":

"Limestone: argillaceous; gray, weathers buff; one massive, well jointed bed; fossiliferous with Syringopora, Chaetetes, and crinoid stems (lower Fort Scott)--"Mulky coal cap rock"--Blackjack Creek limestone of this report . . . 2 feet 6 inches."

There are many exposures of the Blackjack Creek limestone in Johnson County, Missouri. Along the east side of State Highway 13, at the center of the west line of sec. 13, T. 45 N., R. 26 W., it is 4 feet thick and consists of one bed of brown, earthy, slightly crystalline limestone, a description that is applicable to many exposures in Johnson and neighboring counties.

The name Little Osage is here applied to the shale, coal bed, and limestone bed that lie between the Blackjack Creek limestone and the Higginsville limestone. These beds constitute the middle member of the Fort Scott formation.

In Kansas the Little Osage shale is about 5 to 11 feet thick. In the northern part of the outcrop area it is definitely divisible into five parts (beds 8-12 in the section below), which according to Cline's section (1941, fig. 2) persists far northward, owing to the persistance of the included "Summit" coal and Houx limestone, which Cline has identified in Appanoose County, Iowa.

The name Houx limestone was introduced. by Cline (1941, p. 36) for a limestone occurring between the Blackjack Creek and the Higginsville limestones in Missouri, where for a long time, it had been called the "Rhomboidal" limestone because of the manner of fracture of the bed. In Kansas, I have identified the Houx limestone, although somewhat questionably, as far south as southern Crawford County. There it is almost in.contact with.the overlying Higginsville limestone. In some exposures in Oklahoma there is a thin, brown-weathering limestone in the upper part of the Little Osage shale. Because of its position it is believed to be equivalent to the Houx limestone. Wherever identified the Houx limestone ranges from a few inches to little more than one foot thick, is tan, and its texture grades from dense to earthy. Because the Houx limestone, as identified in Kansas, is less than 2 feet thick, and because either it or the shale between it and the overlying Higginsville limestone is lenticular, it is preferable to regard the Houx limestone as a bed in the Little Osage shale member rather than a member of the Fort Scott formation.

The name "Summit" (McGee, 1892, p. 331) is commonly used for a coal bed within the Little Osage shale. When introduced as a name of a coal in Macon county, Missouri, the term was preoccupied in geologic literature by a Pennsylvanian limestone in Pennsylvania. It is not expedient, however, to replace the name. It is a well known term of long usage, and is here regarded as an informal name of a coal bed (see Ashley et al, Art. 16, p. 439). At Fort Scott in Bourbon County, Kansas, the "Summit" coal is .7 foot thick and is 2 1/2 feet above the base of the Little Osage shale. I have not seen this coal bed south of outcrops near Fort Scott. In exposure in which the "Summit" coal is present, shale between the coal and the underlying Blackjack Creek limestone is about 2 1/2 feet thick, thin and evenly bedded, and is gray. In northeastern Bourbon County shale between the "Summit" coal and the overlying Houx limestone consists of about 3 feet of limy shale in the lower part and about 2 feet of black platy shale in the upper part, but at Fort Scott only black shale is present in this zone. In Labette County the Little Osage member is composed almost entirely of dark or nearly black shale but locally there is a limestone questionably identified with the Houx limestone near or at the top.

Type exposure--The exposure in the northeast part of the SE sec. 2, T. 24 S., R. 25 E., Bourbon County, Kansas, on the south valley wall of Little Osage river is the type exposure of the Little Osage shale. The section measured there follows:

| Section at the type exposure of the Little Osage shale, along a north-south road and entrance to a mine draft in the NE SE sec. 2, T. 24 S., R. 25 E., Bourbon County, Kansas. | Feet | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Labette shale | |||

| (24) Covered slope to Pawnee limestone (?) bench | 12.0 | ||

| (23) Shale, covered | 5.5 | ||

| (22) Shale, yellow and gray, clay | 5.5 | ||

| (21) Shale and sandstone, yellow and gray | 5.5 | ||

| (20) Sandstone | 0.3 | ||

| (19) Shale, sandy | 2.3 | ||

| (18) Shale, partly sandy | 5.5 | ||

| (17) Covered interval | 6.0± | ||

| (16) Sandstone and shale, partly covered | 5.5 | ||

| Fort Scott limestone (28.5 feet) | |||

| Higginsville limestone member (11.8 feet) | |||

| (15) Limestone, brown, massive, dense to earthy, hard | 2.3 | ||

| (14) Limestone, poorly exposed | 5.5 | ||

| (13) Limestone, bluish gray, irregularly and thin bedded, brachiopods | 4.0± | ||

| Little Osage shale member (12.0 feet) | |||

| (12) Shale, gray limy, not well exposed | 3.0± | ||

| (11) Houx limestone bed, tan, dense to earthy | 0.4 | ||

| (10) Shale, black | 2.7 | ||

| Shale, limy, fossiliferous | 2.6 | ||

| (9) "Summit" coal bed | 0.7 | ||

| (8) Shale, not well exposed | 2.6 | ||

| Blackjack Creek limestone member (4.7 feet) | |||

| (7) Limestone, brown, dense, massive, weathers buff | 2.4 | ||

| (6) Shale, yellow and gray, limy | 1.1 | ||

| (5) Limestone, tan, earthy | 1.2 | ||

| Cherokee shale | |||

| (4) Shale, nearly black to gray | 3.8 | ||

| (3) Coal, Mulky | 1.8 | ||

| (2) Underclay | 0.9 | ||

| (1) Shale, not well exposed | 16.0 | ||

The name Higginsville is accepted as the name of the upper member of the Fort Scott limestone, which has heretofore been called "upper Fort Scott limestone". It lies next above the Little Osage shale. The name was introduced by Cline (1941, p. 36).

In Kansas the Higginsville limestone is easily separable from the other Fort Scott members everywhere along the outcrop. In many exposures, owing to weathering at the top, the true thickness is difficult to determine, but 16 feet is about the average thickness. This limestone contains Chaetetes, but they are less abundant than in the Blackjack Creek limestone. Fusulinids are common. In general the limestone is irregularly thin-bedded, light gray and crystalline.

Type exposure--Cline (1941, p. 36) states that the Higginsville limestone is well exposed east of Higginsville, which is in Lafayette County, Missouri. The name was suggested to Cline by F. C. Greene of the Missouri Geological Survey. No exact location is given. Cline cites Hinds (1912, pp. 242, 243) who described the Lexington coal, and gave a section measured east of Higginsville, but a description of the Higginsville limestone in the area is not included.

The Labette shale includes beds between the Fort Scott and Pawnee limestones. It was named by Haworth (1898, p. 36) and defined as occurring between the Oswego (Fort Scott) limestone and the Pawnee limestone.

In Kansas on the outcrop the Labette shale ranges from about 40 to 80 feet in thickness, and like the Bandera shale above it, contains much sandstone. There are several coal beds but only one near the top seems to be persistent. For many years there has been confusion in Missouri and Kansas concerning the stratigraphic position of the Lexington coal and its "cap rock." On a recent trip to Lexington, Missouri, L. M. Cline, R. C. Moore, Frank C. Greene, and I were able to identify the "Lexington cap rock" as a member of the Pawnee limestone. It is the limestone now called Myrick Station. In Kansas, however, two fairly persistent coal beds are found a short distance below the Myrick Station limestone. One of these is in the upper part of the Labette shale and one is in the Anna member of the Pawnee limestone as defined in this paper. It is believed that the coal in the Anna shale is the Lexington. This belief is based on description of the Lexington coal and associated beds by Hinds (1912, pp. 233-234), and on Cline's sections (1941, fig. 2, and p. 34) measured in Lafayette County, Missouri. The Anna shale in northeastern Oklahoma contains a lenticular bed of coal, the Lexington (?) coal.

Cline's recent work in Missouri (1941) indicates that there is considerable thinning of the Labette shale between the Kansas outcrops and Jackson and Lafayette counties, Missouri. The decrement in thickness is abrupt, and the occurrence of local limestone breccias as in sec 12, T. 43 N., R. 29 W., Cass County, Missouri, a few feet above the Fort Scott limestone, cause the outcrops to be confusing. Because of their detrital nature and stratigraphic position, these breccias apparently form the basal part of the Warrensburg sandstone. But it should be noted that in western Missouri limestone breccias occur at the base of the Bandera Quarry sandstone and at the base of the Hepler (?) sandstone and in some exposures the stratigraphic position of the tops of the channel fillings cannot be determined. My observations in Johnson County, Missouri, indicate that there is a thickness of about 100 feet of Labette shale and sandstone southeast of Warrensburg in sec. 17, T. 45 N., R. 25 W., but in general the formation is much thinner. Cline (1941, p. 34) measured only a few feet in Lafayette County and at the Houx ranch in Johnson County.

The name Englevale sandstone was introduced for a sandstone in the Labette shale by Pierce and Courtier (1935, pp. 1061-1064) from the village of Englevale in Crawford County, Kansas. This sandstone was described as having an average width of outcrop of 0.4 mile and as having been traced for a distance of 9 miles in a north-northeast direction. Such a description, implying as it does that there is a single continuous layer of sandstone, is misleading, because over a distance of a few hundred miles, there is much sandstone in the Labette shale, but the sand bodies are lenticular and at least in part are channel fillings. The disconformity or disconformities at the base of lenses are not indicative of periods of erosion that were of long duration. In the area of present outcrops there was deposition of mud and sand, and very minor amounts of limestone and coal. In northeastern Oklahoma there is much sandstone in the Labette shale. In some exposures two massive sandstones have a limestone between them. In some papers this limestone has been miscorrelated with the "Lexington cap rock" (Myrick Station member of the Pawnee limestone). Seemingly, for the greater part of Labette time the area lay above sea level, and there were local and temporary cutting and filling of channels. As far as has been observed, the deepest channeling took place in the vicinity of Warrensburg (and possibly near Moberly), Missouri. At Warrensburg the Fort Scott limestone was entirely removed, but the position of the base of the channel is not definitely known there, as the sandstone may be in part Cherokee sandstone. The statement (Pierce and Courtier, 1938, p. 46) that in Kansas the Englevale sandstone cuts partly or entirely through the Fort Scott limestone cannot now be verified at the places cited. At one exposure, "just north of the east-west road half a mile north of town," (SE sec. 13, T. 28 S., R. 24 E., Crawford County, Kansas) and in which place the base of the sandstone is stated to be about 4 feet above the base of the Fort Scott limestone, it appears to me that recent slumping gives the appearance of sandstone cutting out the upper part of the Fort Scott limestone.

Unless the name Warrensburg sandstone is to be restricted to a particular body of sandstone in the Labette shale, the term is available for application to other sandstone lenses occurring at its stratigraphic position and has priority over Englevale. It seems preferable to apply the name Warrensburg collectively to sandstones of the lower part of the Labette shale even though they occur at slightly different stratigraphic horizons. These are equivalent to the sandstones included under the familiar subsurface term "Peru" sand.

It is obvious that much more study is needed to determine the true stratigraphic relationships within the Labette shale, and the same is true of the Bandera shale above. In all probability the local coals, thin limestones, and sand bodies will reveal the presence of several cycles of deposition, and it is now believed that in Kansas a part of the sand in each of these two shales was deposited late in the respective time intervals and represents the beginning of megacyclothems that include the overlying limestone formations. In southeastern Kansas and in northeastern Oklahoma there is a rather persistent limestone in the middle part of the Labette shale.

Type locality--The village of Labette in Labette County, Kansas, has been designated as the type locality for the formation (Haworth, 1898, p. 36). As a pro tempore type exposure I am here designating the somewhat poor exposure beginning near the middle of the north line and extending to a point near the northeast corner of sec. 22, T. 33 S., R. 20 E., near the town, Labette. There are at present no good exposures of the Labette shale known near Labette, and it seems that more detailed information will be gained only from small artificial exposures that may be made from time to time.

The Pawnee limestone lies between the Labette and Bandera shales, hence it is the first prominent limestone assemblage above the Fort Scott limestone. It has generally been described as comprising a single ledge, and Swallow (1866, p. 24) applied the name Pawnee to "heavy bedded, porous and compact, coarse and fine, drab, brown and bluish-gray, cherty, concretionary and mottled (limestone), 20 to 25 feet thick." It is true that in the type locality and farther south the two prominent limestone members of the Pawnee are nearly or quite in contact with one another, but anyone acquainted with the members farther north in Kansas can easily differentiate them everywhere along the outcrop.

Moore (1936, p. 62) noted "a thin bed of blue dense limestone with vertical joints separated from the upper limestone beds by two feet or more of black platy shale." He had reference to the persistent bed, a few inches thick, that lies at the base of the shale which I am naming the Anna shale member. The thin limestone is separated from the Myrick Station limestone by about 2 feet of black platy shale with phosphatic concretions. This thin nearly black slabbly limestone is present in nearly all Kansas exposures of this part of the formation and is identified far into Missouri and Oklahoma. It is the lowest limestone in the Pawnee assemblage and marks the beginning of limestone deposition over a large area. Moore really amended the definition of Pawnee limestone to include this bed, but it is not, as surmised by McQueen and Greene (1938, p. 25), the "Lexington cap rock" which is the Myrick Station limestone (Cline, 1941, p. 37). 1 am not applying a name to this limestone bed inasmuch as it is so thin, but instead am regarding it as the basal part of the Anna shale, which I designate in this paper as the basal member of the Pawnee formation. Outcrops that I have studied in Oklahoma show that in Nowata County this limestone at the base of the Pawnee formation is thicker than in any of the known Kansas or. Missouri exposures. In some Oklahoma exposures it comprises more than one ledge. As stated elsewhere in this paper there is some evidence that the unnamed basal Pawnee limestone thickens abruptly in Tulsa county, Oklahoma, and constitutes the greater part of the Oologah limestone. When a name is given to this limestone, the definition of the Anna shale should be amended so as to exclude it. From the data at hand it is clear that the black phosphatic concretion bearing shale that comprises the main part of the Anna shale of Kansas is contiguous with the main shale break in the Pawnee limestone of northeastern Oklahoma and that the Mine creek member thins to a feather edge.

In this paper I am designating the members of the Pawnee formation in ascending order as follows: Anna shale, Myrick Station limestone, Mine Creek shale, and Laberdie limestone. Each is described separately below.

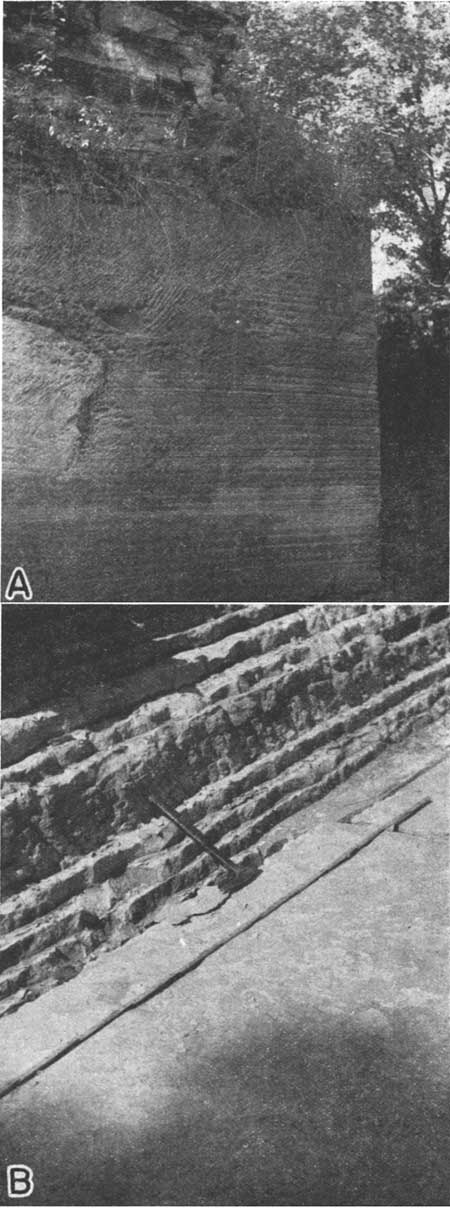

Plate 3--A, Characteristic topography on the dip slope of the Pawnee limestone, southern Bourbon County, Kansas. B, An exposure of the upper part of the Labette shale and lower part of the Pawnee limestone, south of the center of sec. 7, T. 27 S., R. 24 E., Bourbon County, Kansas. The hammer is on a thin limestone in the base of the Anna shale. This is the type exposure of the Pawnee limestone and of the Anna shale member.

Type exposure--The type locality of the Pawnee limestone has not been designated more definitely than is indicated by the following quotation: "on Pawnee Creek near the village of Pawnee southwest of Fort Scott, Kansas" (Moore, 1936, p. 62). The village of Pawnee is now called Anna. South of the Marmaton river in Bourbon County the Pawnee limestone forms broad dip slopes covered by soil and indigenous vegetation, mostly native blue-stem grass. There are many bare cliffs exposing mainly the middle and upper part of the formation along the valley walls of the tributaries to the Marmaton river. Pawnee creek is one of these tributaries. Because it is desirable that the type exposure show units that are regionally significant, I have selected as the type the exposure along State highway 7, slightly north of the center of sec. 7, T. 27 S., R. 24 E., Bourbon County. The upper 20 to 25 feet is not well exposed there, but can be seen fairly well at the middle of the east line of sec. 2, T. 27 S., R. 24 E. This section is also regarded as the type exposure of the Anna shale member. The measured section at the designated type exposure follows.

Plate 4--An exposure of the Blackjack Creek limestone, sec. 16, T. 27 S., R. 25 E., Bourbon County, Kansas. The arrows point to Chaetetes colonies. The coralline limestone here represents a higher phase of the Blackjack Creek cyclothem than is present at Fort Scott. See plate 2.

| Section at the type exposure of the Pawnee limestone, including type exposure of the Anna shale member near the center of the N2 S2 sec. 7, T. 27 S., R. 24 E. Bourbon County, Kansas | Feet | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pawnee limestone | |||

| Laberdie limestone member (25 feet±) | |||

| (9) Limestone, mostly covered | 20-25 | ||

| (8) Limestone, light gray, slightly crystalline, wavy and thin beds, slightly more massive near base. Giant cup corals in part, and Chaetetes near base, exposed in vertical section. | 5.4 | ||

| Mine Creek shale member | |||

| (7) Shale, slightly carbonaceous | 0.25 | ||

| Myrick Station limestone member | |||

| (6) Limestone, brown and gray, very slightly crystalline, generally earthy, massive, but thinner bedded near top "worm borings", large fusulinids | 1.5± | ||

| Anna shale member (1.8 feet) | |||

| (5) Shale, gray | 0.3 | ||

| (4) Shale, black, fissile, small black concretions | 1.1 | ||

| (3) Shale, gray, small oblong phosphatic concretions | 0.1 | ||

| (2) Limestone, dark, nearly black, crystalline to earthy, slabby, mostly irregular lenses | 0-0.3 | ||

| Labette shale | |||

| (1) Shale, dark gray, thin coal bed near top | |||

As indicated above, the Anna shale includes in ascending order (1) local thin, dark, slabby limestone and (2) black, platty and locally fissile shale. These strata lie next below the Myrick Station limestone. They are included in the Pawnee limestone and are designated as comprising its basal member in Kansas. As shown in plate 1, the Anna shale is identifiable across Kansas. It is present far into Missouri and Oklahoma.

The Anna shale is the lowest member of the Pawnee limestone in Kansas. It is mostly black and platy but locally the black shale is fissile. It commonly bears small black phosphatic concretions. Locally there is gray shale in the upper and lower parts, and in some places, as in sec. 11, T. 25 S., R. 24 E., Bourbon County, Kansas, and in sec. 27 T. 29 N., R. 18 E., Craig County, Oklahoma, it contains a coal bed which is probably the Lexington coal of Lafayette County, Missouri. The black shale is the most persistent part. At its base is a thin, slabby limestone, varying from crystalline to earthy, which is locally absent but which is much thicker in Oklahoma and which may be the main part of the Oologah limestone. In Kansas the thickness of the Anna shale ranges from about 3 to 11 feet. The shale is exposed at many places along with the overlying Myrick Station limestone. More detailed description will be given in a later report on Marmaton stratigraphy, but some features are shown in plate 1 of this paper.

Type exposure--The type exposure of the Anna shale is the same as that of the Pawnee limestone, that is, a little north of the center of sec. 7, T. 27 S., R. 24 E., in Bourbon County, Kansas on Kansas highway 7. The features shown there are described in the paragraph above in which is described the Pawnee limestone in its type exposure.

The term Myrick Station limestone is accepted as the name of the second member from the base, in the Pawnee limestone in Kansas. Cline (1941, p. 37) applied the name to the "Lexington caprock" in its exposure near Myrick Station on the Missouri river in Lafayette County, Missouri. The same limestone is easily identified in numerous exposures across Lafayette, Johnson, Cass, and Bates counties, Missouri, into Linn County, Kansas. In Missouri it is much the same as in its northernmost Kansas occurrence.

In Kansas the Myrick Station limestone is identified throughout the length of the line of Pawnee outcrops. However, there may still be some question as to the position of the contact of the Myrick Station limestone with the overlying Laberdie limestone in some of the southern exposures. In Nowata County, Oklahoma, the boundaries of all members of the Pawnee limestone have been clearly identified. The Myrick Station member is characteristically brownish-gray, massive, and somewhat earthy in the lower part. The average thickness is about 4 feet, but a thickness of 8 feet has been measured in sec. 11, T .25 S., R. 24 E., Bourbon County. In this and neighboring exposures the limestone is divided by a thin shale parting and the upper part of the limestone contains Chaetetes. As yet, the top has not been certainly distinguished in some southern exposures, but it it probable that part of the Chaetetes-bearing limestone in the Pawnee in Labette County is the upper part of the Myrick Station member. The lower, massive part of the limestone is easily identified there.

Type exposure--Cline (1941, p. 37) has designated "as the type section outcrops in ravines in the south bluff of the Missouri River near Myrick Station, just west of Lexington county, Missouri." His section (Cline, 1941, sec. 2, p. 34) measured "in the vicinity of Lexington" includes:

| Feet | Inches | |

| "Limestone (Myrick Station member of Pawnee); light gray, fine grained, hard, conchoidal fracture, wavy bedding but weathers massive | 5 | 5 |

| Shale: black, carbonaceous, slaty | 1 | 4 |

| Coal (Lexington) | 1 | 6" |

In Kansas north of Marmaton river and in Missouri the Pawnee limestone includes a definite shale units between the Myrick Station and Laberdie members. To this shale I am applying the name Mine Creek shale member. It can be identified certainly in some exposures south of Marmaton river and as far south as a point 20 miles south of the Kansas-Oklahoma line. The lack of definite identification in some locations indicated on plate 1 is probably due to obscurity of exposures.

Where more fully developed in Kansas, as in Linn County, the Mine Creek shale is mostly gray, but more or less carbonaceous, and it contains a thin bed of limestone in the upper part, and black shale like that in the Little Osage shale member of the Fort Scott limestone. Toward the south the black shale is the most persistent part of the Mine Creek member. The thin limestone near the top seems to correspond cyclically to the Houx limestone in the Little Osage shale. The maximum thickness of the Mine Creek member in Kansas is about 16 feet.

Type exposure--The type exposure of the Mine Creek shale is near the middle of the south side of sec. 23, T. 21 S., R. 25 E. on a tributary of Mine creek in Linn County, Kansas. There is another good exposure at the type exposure of the overlying Laberdie limestone in sec. 6, T. 23 S., R. 25 E., Linn County. The section measured at the type exposure follows, and the other section is described in connection with the description of the type exposure of Laberdie limestone.

| Section at the type exposure of the Mine Creek shale at the center of the south side of sec. 23, T. 21 S., R. 25 E., Linn County, Kansas | Feet | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Altamont limestone (exposed at top of hill near school house east of Pawnee limestone exposure) | |||

| Worland limestone member | |||

| (18) Limestone, light in color, nodular in basal part | 2.0± | ||

| Lake Neosho shale member | |||

| (17) Shale, not well exposed, mostly gray, but a zone of black shale contains phosphatic concretions | 3.0± | ||

| Tina limestone member | |||

| (16) Sandstone, gray, micaceous, calcareous, massive | 0.5 | ||

| (15) Sandstone, gray, micaceous, shaly | 0.5 | ||

| Bandera shale | |||

| (14) Shale, gray, calcareous, and limonitic | 3.0 | ||

| (13) Sandstone, gray, micaceous, shaly | 2.0 | ||

| (12) Shale, gray and yellow, limonitic, one thin bed of sandstone about 3 feet from top, lower part less limonitic, and more blocky, large septarian concretions about 17 feet above base | 32.5 | ||

| Bandera shale and Pawnee limestone | |||

| (11) Covered portion including lower few feet of Bandera shale, in which is the Mulberry coal, mined nearby, and the upper part of the Laberdie member, Pawnee formation, exposed in a quarry a short distance south of road | 10.8 | ||

| Pawnee limestone | |||

| Laberdie limestone member (lower part) | |||

| (10) Limestone, bluish gray to light gray, dense, sparingly fossiliferous | 1.5 | ||

| Mine Creek shale member (16.5 feet) | |||

| (9) Limestone and calcareous shale, abundantly fossiliferous, fauna mostly brachiopods | 0.5 | ||

| (8) Shale, gray, fossiliferous | 3.0± | ||

| (7) Coquina of brachiopods | 1.0-0.5 | ||

| (6) Shale, green near top, mostly gray, somewhat carbonaceous, blocky, limonitic | 12.0-13.0 | ||

| Myrick Station limestone member | |||

| (5) Limestone, dark bluish gray, weathers brown, tipper part thin bedded, lower part massive, large fusulinids in upper part | 3.7 | ||

| Anna shale member | |||

| (4) Shale, gray | 0.5 | ||

| (3) Shale, black, platy | 1.5 | ||

| (2) Limestone, black, slabby | 0.2± | ||

| Labette shale | |||

| (1) Shale, contains thin coal bed near top. | |||

The upper member of the Pawnee limestone is here named the Laberdie limestone member. In Kansas, north of Marmaton river, it is distinctly separated from the lower part of the Pawnee limestone by several feet of shale. The same conditions obtain in Missouri (Cline, 1941, p. 37). Farther south in Kansas the separating shale (Mine Creek) is much thinner and may be locally absent, but the underlying darker, more massive Myrick Station limestone can be differentiated from the lighter-colored, more crystalline, and thinner-bedded Laberdie limestone in numerous natural and artificial exposures. West of Verdigris river, about 4 miles east of Nowata, Oklahoma, all members of the Pawnee formation are well exposed, but the Mine Creek shale is very thin there.

The Laberdie limestone is defined as the upper member of the Pawnee limestone, and as the part lying above the Mine Creek shale where that member is present.

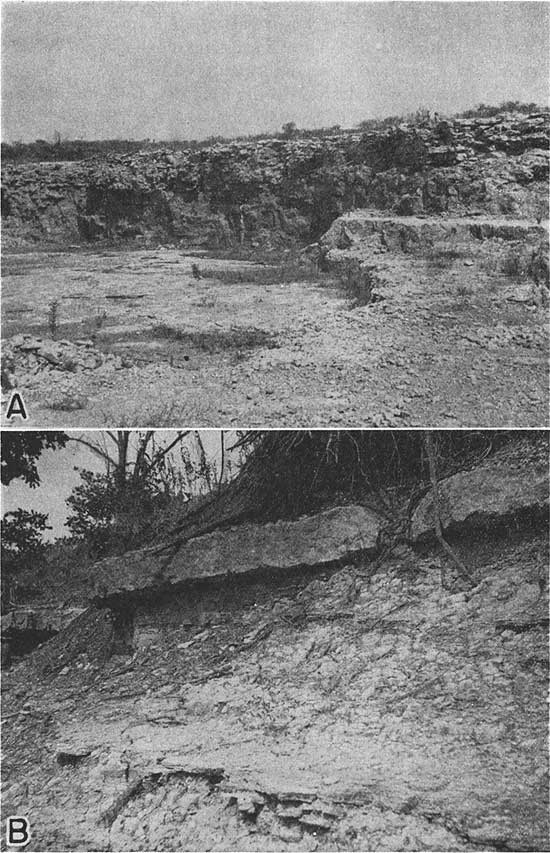

North of Marmaton river natural outcrops of the Laberdie limestone are somewhat scarce but it is exposed in many artificial excavations. In contrast to this, the Myrick Station limestone is naturally exposed nearly continuously along its strike, forming a weathered brown massive ledge above an exposure of black, platy Anna shale. In this part of the state the Laberdie member is somewhat thin-bedded, light gray, and crystalline, and locally contains colonies of the coral Chaetetes. In southern Linn County it is asphaltic (Jewett, 1940, p. 12). South of Marmaton river this limestone makes extensive dip slopes and has been eroded into picturesque cliffs (pl. 3A). The thickness increases southward and ranges from about 8 to 30 feet.

Type exposure--The exposure (mostly artificial) in a quarry in the southwestern part of sec. 6, T. 23 S., R. 25 E., 1 miles west of Prescott, Linn County, Kansas, is designated as the type exposure of the Laberdie limestone. The name is from Laberdie creek, which is about 100 feet west of the quarry. The section measured there is given below.

| Section at the type exposure of the Laberdie limestone, in the southwest corner of sec. 6, T. 23 E., R. 25 E., Linn County, Kansas. | Feet | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pawnee limestone | |||

| Laberdie limestone member | |||

| (2) Limestone, light gray, thin wavy irregular beds, weathers somewhat lighter in color than when fresh; more massive in lower part | 6.0 | ||

| Mine Creek shale member | |||

| (1) Shale, and thin beds of limestone not well exposed, but cropping out with myriads of fossils in road ditch below quarry and east of Laberdie Creek | 6.± | ||

| Note: The Myrick Station member is partly exposed when water in Laberdie creek is low. | |||

The Bandera shale lies above the Pawnee limestone and below the Altamont limestone. It was named by Adams (1903, p. 32) and the name has been applied uniformly according to the original definition.

In Kansas along the outcrop the thickness of the Bandera shale does not vary greatly from 50 feet, although in some places it may be as small as 40 feet. The formation includes much sandstone, a part of which fills definite channels. The shale portion is generally gray. Limonite concretions and stringers are common. The Mulberry coal bed lies near the base.

The sandstone in the Bandera formation is interesting and deserves extensive study, which should lead to a better understanding of Pennsylvanian sedimentation in Marmaton time. Preliminary studies have indicated that the sandstone that fills the channels is overlain by shale that is distinguishable chiefly by its reddish-purple color, from what must be slightly older shale that does not overlie the filled channels. The latter is more limonitic, gray, and grades laterally into sandstone and sandy shale. An abundance of fossil plant material occurs in sandy shale, especially near the underlying Mulberry coal.

The Bandera flagstones are quarried from the Bandera formation in Bourbon County. The formation is named from the quarries at Bandera. Here the sand is firmly indurated by cement that is at least in part siliceous. In the Bandera quarries the sand is fine, micaceous, and somewhat ripple-marked, and bears numerous fossil annelids (pl. 5).

The Mulberry coal bed was named (Hinds, 1912, p. 75) from Mulberry creek in Bates county, Missouri. It is identified southward in Kansas nearly to the southern Bourbon County line. It occurs generally about 3 feet above the base of the formation. The maximum thickness is about 2 feet. This coal is mined in Linn and Bourbon counties and in Missouri.