Prev Page--Structure, Climate || Next Page--References

Economic Geology

Within the past 80 years the Permian redbeds of Kansas have yielded building stone, clay for bricks, gypsum, salt, paint pigment, riprap, and road material. At the present time, however, commercial production from the Leonardian and younger Permian rocks is (with the exception of one brick plant) limited to the evaporites in the section-salt, gypsum, and dolomite.

Starting with the evaporites, the various commercial materials and the history of their utilization (so far as it is known to me) are described briefly in this chapter. There will also be some mention of potential ceramic uses of some of the silty clays.

Halite

All the Permian salt beds which have been exploited commerically for salt to date are restricted to the Hutchinson salt member of the Wellington formation. The history of development of Kansas salt industry has been ably summarized by Taft (1946) and much of the following discussion is adapted from his report.

The Hutchinson salt member at Hutchinson was first discovered in 1887 by Ben Blanchard, who was prospecting for oil. By 1888 salt was being produced from brine wells by 13 different plants, with an annual production of 900,000 barrels. The number of producers operating in any one year has varied greatly since that time, but from 1889 to the present, Kansas has been among the top five salt-producing states. In 1952, the total Kansas production was 911,744 short tons, having a dollar value of $6,850,027 (W. H. Schoewe, personal communication). Average annual production is about 800,000 tons.

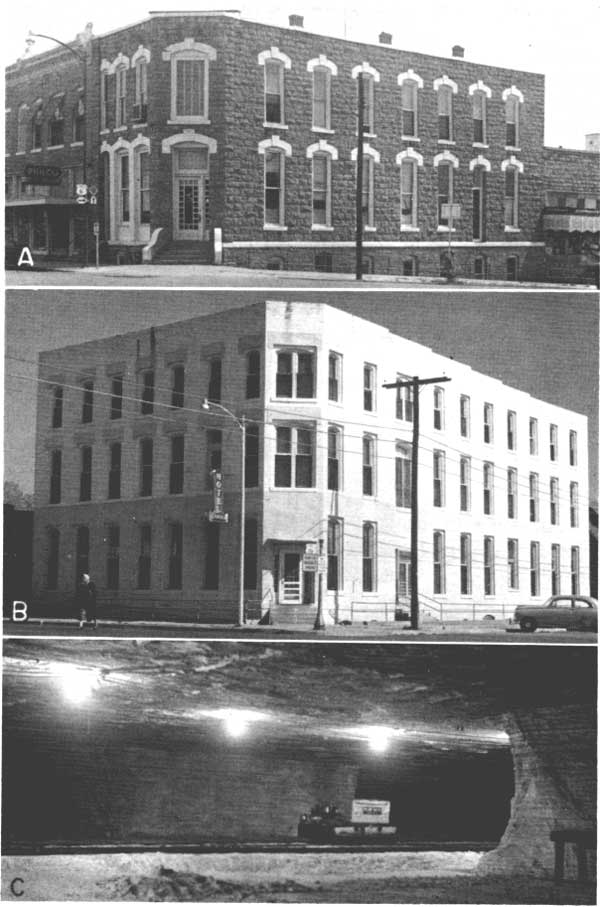

Five mines are in operation at the present time, and several wells also produce salt. They are located at Lyons, Kanopolis, and Hutchinson. A view of the Carey Salt Company mine at Hutchinson is shown in Plate 24C. This mine, which has been in operation since 1923, is producing from a 7 to 12-foot layer of salt 645 feet below the surface.

Salt beds farther west and stratigraphically higher are used for storage of hydrocarbons.

Commercial deposits of potassium minerals have not yet been found in Kansas salt beds, although small quantities of polyhalite have been described from several localities (Smith, 1938; Runnels, Reed, and Schleicher, 1952; Swineford and Runnels, 1953). Minable quantities of potassium salts conceivably may be discovered in the future.

Gypsum and Anhydrite

Within the area of this report, commercial deposits of gypsum are restricted to the Blaine formation. To the north, however, older Permian rocks contain workable gypsum deposits. In the vicinity of eastern Saline County are several layers of minable gypsum in the Wellington formation. Still farther north, in Marshall County, gypsum is mined from the Council Grove group of late Wolfcampian age.

The only active mine in the Blaine formation is located in the Medicine Lodge member southwest of Sun City in Barber County, where the gypsum attains a total thickness of about 30 feet. The mine is operated by the National Gypsum Company, and the rock is processed in a mill at Medicine Lodge.

Blaine gypsum has also been mined in other near-by areas. Several abandoned pits may be seen in the vicinity of sec. 19, T. 30 S., R. 15 W., in the northwest corner of Barber County. The gypsum industry in Kansas started in 1872 in Blue Rapids, but the first mill in the southern Kansas area was not built until 1889 (Jewett and Schoewe, 1942, p. 140).

Thin discontinuous beds of gypsum in the Wellington formation have been exploited occasionally in southern Marion County, northeast Sedgwick County, and eastern Sumner County, four miles northwest of Geuda Springs (Grimsley and Bailey, 1899, p. 69). Gypsum was mined for building stone at this last locality sometime between 1878 and 1889 (Hay, 1890; Grimsley and Bailey, 1899, p. 69), and the cut stone was used in a large business block in Wellington.

The gypsum is normally used as a retarder in Portland cement, as plaster of Paris, cement plasters, and fabricated products such as wall board and insulating material.

Anhydrite is produced at the Sun City mine and is discarded at the site. This waste product may conceivably become a minor source of sulfur in the future. In England and Germany anhydrite is treated with ammonium hydroxide and carbon dioxide for the manufacture of ammonium sulfate. In England sulfuric acid and Portland cement are made from anhydrite (E. K. Nixon, personal communication). Anhydrite is used in some areas--notably Virginia--as a soil conditioner. Much research has been done on the use of anhydrite as a retarder in Portland cement, and in plaster. The general sparseness of resistant rock in the area has led to some use of anhydrite as facing material in earth dams for stock ponds; conceivably it may last until the pond is silted. The mineral might perhaps be used for some diluents or fillers.

Dolomite

Two dolomites thick enough to be of commercial value exist in the stratigraphic section of the area. These are the Stone Corral of Rice County and the Day Creek dolomite in Clark County.

The Stone Corral, which attains a maximum thickness of 6 feet, is quarried along the southwestern bluff of Little Arkansas River, in eastern Rice County, as in sec. 15, T. 20 S., R. 6 W. The dolomite is used as crushed rock and formerly also was quarried for building stone (Fent, 1950, p. 15).

The Day Creek dolomite, which maintains an average thickness of 2.5 feet over a large area in Clark County, is more uniformly dense than the Stone Corral, and in many localities has very little overburden. It has been used as crushed rock for roads and as riprap for earth banks, as at the U. S. Highway 160 bridge over Kiger Creek. It was formerly used as a building stone, and was reported to be durable but difficult to trim because of its erratic fracture (Cragin, 1896, p. 44),

The two dolomite formations are potential sources of magnesium (Jewett and Schoewe, 1942, p. 111).

Ceramic Raw Materials

In the early days of Kansas settlement, the general scarcity of lumber and building stone in the area promoted the use of local shales and siltstone for building brick. Some of the structures made from local bricks are still standing. One of the most impressive of these is the hotel in Medicine Lodge (Pl. 24B). Raw material for the bricks used in this building was obtained from the Cedar Hills sandstone in a canyon southwest of Medicine Lodge (S2 sec. 15, T. 32 S., R. 12 W.) in the 1880's (George Horney, oral communication). It is chiefly red feldspathic argillaceous siltstone.

Plate 24--A, Building in Caldwell, built of stone from Ninnescah formation. B, Hotel in Medicine Lodge, built of brick made from Cedar Hills sandstone. C, Interior of Carey Salt Company Mine, Hutchinson.

Several brick plants were utilizing shale from the Wellington and Ninnescah formations in the period from 1920 to 1930. Landes (1937, p. 87) reports that clay (from the Wellington formation) was utilized in Wichita in two plants, one a face brick plant, and the other a brick and tile plant. Neither plant was operating as late as 1936. In 1918 a plant was producing ordinary brick from the Wellington formation at Marion. Ninnescah shale was used at approximately the same time in Lindsborg for the manufacture of common bricks. A brick plant in Salina has been using clay from the Wellington formation from 1920 to the present day.

According to Norman Plummer (oral communication) clay from the Ninnescah shale is in general more satisfactory for the manufacture of bricks than is clay from the Wellington formation. The Wellington clay has a rather short firing range owing to its high calcium carbonate content.

Samples from the Wellington and Ninnescah formations have been tested for use as lightweight ceramic aggregate (Plummer and Hladik, 1951, pp. 63-64). Satisfactory aggregate can be produced from the Ninnescah shale, particularly if a sintering machine is employed.

Plummer (oral communication) also reports that shale from the Ninnescah formation makes an excellent brown slip glaze for insulators.

Miscellaneous Uses

Building stone has been produced at various times in the past from thin resistant beds in the Leonardian and Guadalupian section. Building stone from the Stone Corral and Day Creek dolomites and from a gypsum bed in the Wellington formation have been mentioned in the foregoing sections. Other formations which have supplied building stone include the Ninnescah shale, Harper sandstone, and Whitehorse sandstone.

Dense, calcareous fine-grained sandstone, or, more properly, coarse-grained siltstone from the lower part of the Ninnescah shale has been quarried south of Caldwell, Sumner County, and was formerly used extensively as building stone in that city. Several buildings erected half a century ago are still in use and are apparently in good condition (Pl. 24A). According to Norton (1939, p. 1770) a sandy limestone in the Ninnescah (his bed 3) has been quarried along the outcrop as foundation stone for farm buildings.

Thin sandy siltstones of the Harper formation were at times quarried extensively for dimension stone. Norton (1939, p. 1783) reports fairly recent production of such stone from a series of bench-forming, well-cemented, even-bedded hard sandstones in the lower part of the Chikaskia member. Toward the end of the nineteenth century soft, brownish-red mottled siltstone from the Harper and underlying Permian redbeds was quarried at several localities near Harper, Kiowa, Hazelton, Attica, Milan, Spivey, Arlington, and other towns (Cragin, 1896, pp. 18-19) for dimension stone. According to Cragin, this material was soft enough to be dressed fairly easily, but became harder by seasoning, and constituted an excellent dimension stone. Very few structures built from this material, however, are still in existence. In the City of Harper, a few sandstone buildings are still standing, but much of the stone is crumbled and patched. In the course of the field work for the present study, an attempt was made to find some of the old quarries near Harper. However, the rock was apparently so soft that the quarries are no longer recognizable as such. A siltstone bed exposed in a road ditch in the SW sec. 29, T. 32 S., R. 6 W., Harper County, is reported by a long-time resident to have been quarried for building stone. Most of the beds utilized were from 8 to 18 inches thick. The rock tends to slake off fairly rapidly on exposure to the weather, and rounded, bulging surfaces are produced.

Cragin (1896, p. 42) referred to the use of selected portions of the Whitehorse sandstone (Red Bluff) for building stone, and described the material as "fairly durable." He did not give locations of any quarries or structures.

During an indefinite period prior to 1896, red and gray silty shales from the Harper formation near Kingman were exploited for paint pigment. According to Cragin (1896, p. 20), these shales "form the basis of the 'Cherokee Brown Mineral' and 'Silver Gray' manufactured by the Kingman Paint Company, and which has had considerable demand in the paint-trade of Topeka, Kansas Ccity, and other markets."

The only other use of the upper Permian rocks, known to me, is as a fill for road beds and as a topping for secondary roads. Rock for road fill has been removed by most counties from most of the formations. Some of the shale is reported to pack down and form a hard surface on roads. At one time soft limestone from the Wellington formation was used for surfacing, but it was found to be too dusty.

Prev Page--Structure, Climate || Next Page--References

Kansas Geological Survey, Geology

Placed on web Aug. 25, 2006; originally published May. 1955.

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

The URL for this page is http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/Bulletins/111/07_econ.html