Prev Page--Physiography || Next Page--Lower Cretaceous

The Upper Permian and The Lower Cretaceous

by Charles S. Prosser

Contents

The Upper Limit in Eastern Central Kansas

Introduction

Review of Former Maps

Map of Prosser and Beede

Marion

Wellington

The Cimarron Series or Red-Beds

Historic Review

Description

Correlation

Classification

Review of previous work

Classification

Cheyenne sandstone

Kiowa shales

"Dakota" Sandstone of Southern Kansas

Distribution

Kiowa-Barber-Comanche Area

Southern Comanche Area

Clark Area

Discussion of the Sections

Kiowa of Central Kansas

The Mentor Beds

Description

Distribution

Correlation

References to description of the Mentor fauna

The Upper Permian

The Upper Limit in Eastern Central Kansas

Introduction

In central Kansas, particularly in Dickinson, Saline, McPherson and Marion counties the line of separation between the Permian and Cretaceous systems has been drawn quite differently on the various geological maps of Kansas. The greatest variations are found in the wide valley of the Smoky Hill river from the mouth of Solomon river to above Lindsborg; and the high divide between the Smoky Hill river and the branches of the Arkansas and the Cottonwood rivers which extends across the northern part of McPherson and Marion counties and north into the southern part of Dickinson and Saline counties.

Review of Former Maps

Professor Mudge in 1878 (First Biennial Report State Board Agriculture of Kansas, p. 47) published a "Map showing the superficial strata of Kansas" on which the base of the Cretaceous is represented as crossing the Smoky Hill river valley near the mouth of the Solomon river, thence extending southerly along the Dickinson-Saline county line; next turning easterly and crossing the southern part of Dickinson County and extending two thirds of the distance across the central part of Morris County; finally turning southwesterly across the southwesterly part of Morris, diagonally across Marion and the southeastern corner of McPherson County.

On the "Geological Map of Kansas" by Professor St. John in 1883 (Third Biennial Report State Board Agriculture of Kansas, opposite p. 575) the Cretaceous is represented as crossing the Smoky Hill river near Bridgeport, about fifteen miles south of Salina, (all of the river valley and Saline and Dickinson counties to the east being represented as belonging in the "Upper Coal Measures"), then extending easterly across southern Saline and Dickinson counties into the southwestern part of Morris, when it turns southwesterly across the northwestern part of Marion and the southeastern and southern part of McPherson.

The line just described on St. John's map was followed practically by Doctor Williston on his geological map of Kansas published in 1892.

The "Geological and Topographical Map of Kansas" by Professor Hay in 1893 (Eighth Biennial Report State Board of Agriculture) represented the base of the Cretaceous system in these counties more accurately than it had been given on the former maps. The top of the river bluffs from northwest of Abilene to the vicinity of Salina were shown as the base of the Cretaceous, then the line ran considerably to the west of the river across the wide valley of the central part of Saline County, bending easterly around the Smoky Hill buttes, crossing the Smoky Hill river near Marquette, then following the bluffs south and east of the river until opposite the city of Salina. The divide between the Smoky Hill river and Gypsum creek, in the eastern part of Saline County, was given as Dakota; the line turning easterly at the southeast corner of Saline County and crossing the extreme southern part of Dickinson County and the southwest corner of Morris County where it made a loop turning westerly across the northern part of Marion County to the northeast corner of McPherson which it crossed diagonally in a southwesterly direction.

Finally in 1896 (The University Geological Survey of Kansas, Vol. 1, Pl. XXXI) Professor Haworth published "A Reconnaissance Geologic Map of Kansas" on which so far as the geology of the Smoky Hill valley is concerned, there is an approximate return to the geological map of Mudge. The Dakota is represented as covering all of Saline County, except a very small area on the central part of the Saline-Dickinson County line. The base of the Dakota is shown as crossing the Smoky Hill river at the mouth of the Solomon river, when it runs southeast about one third of the distance across Dickinson County, then turns southwest and runs across the Saline-Dickinson County line, turning southeast across the southwestern part of Dickinson County to about the middle of the Dickinson-Marion county line, when it turns southwest with a somewhat irregular line crossing the northwestern part of Marion County and southeastern part of McPherson County.

Map of Prosser and Beede

It was planned to accurately trace the line of separation between the Permian and Cretaceous systems over all the area under consideration; but it became necessary to bring the field work to a close before this had been accomplished. However, the work as far as it was finished showed conclusively that the broad valley of the Smoky Hill river in the central part of Saline County is underlain by the Permian which extends even farther up the river valley than represented to do by Hay; that the upper part of the divide in the eastern part of Saline County between the Smoky Hill river and Gypsum creek is composed of Cretaceous rocks; and finally that on the high divide between the headwaters of the Cottonwood and the southern branches of the Smoky Hill and northern branches of the Arkansas, the Dakota does not enter the southern part of Dickinson County, but only extends about six miles into Marion County to a point about two miles southwest of Durham village in Durham Park township.

Over a part of Saline County at or near the base of the Cretaceous, as represented in that county, is an iron-brown sandstone that contains, in places, abundant fossils. This zone has recently been named "the Mentor beds" by Professor Cragin and referred to the Comanche series (F. W. Cragin, American Geologist, Vol. XVI, Sept. 1895, 162-166). The nonfossiliferous bluish-gray, greenish, and reddish shales overlying the fossiliferous Marion formation of the Permian, which are well represented west of the Smoky Hill river in the central part of Saline County, have been mapped in the Permian. For these shales, which may be regarded as constituting a formation, Professor Cragin has proposed the name Wellington shales (F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, Vol. VI, pp. 3, 16-18) and mentioned their occurrence in Saline County along "the foot of the bluffs of Spring creek from Salina to a point in the southwest vicinity of Bavaria" (F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, Vol. VI, p. 17).

On the northern bank of the Saline river in the northern part of Saline County the Dakota (including the Mentor beds) forms the upper part of the river bluffs. Five miles north of the city of Salina, in the western part of Cambria township, the base of the Dakota is between 90 and 100 feet above the level of the Saline river, or approximately 1300 feet above sea level. On the Salina sheet of the U. S. topographic map the 1300 foot line has been taken as the approximate line of division between the Permian and Cretaceous systems for that part of the sheet north of the Saline river. From the south side of the Saline river to the ridge southeast of Brookville the line on the map is only an approximation; but from that point along the ridge south of Bavaria, east of Soldier Cap mound, near Falun and around the northern, eastern, and southern flanks of the Smoky Hill buttes the line was traced with some care. To the south and east of Smoky Hill river in the northern part of McPherson County, on the western side of the divide between the Smoky Hill river and Gypsum creek, the line was traced by Mr. Beede. In Saline County the writer traced the line down the western and up the eastern sides of the divide between the Smoky Hill river and Gypsum creek into the northeastern part of McPherson County, in Delmore and Rattle Hill townships. The line around the divide between the Smoky Hill, Cottonwood and Arkansas rivers in the northeastern part of McPherson and northwestern corner of Marion County was mostly traced by Mr. Beede, as well as the line in the western part of Marion County and the northern part of Harvey between the Permian and Tertiary or Quaternary sand. Mr. Beede also traced the greater part of the boundary of the deposit of sand in Marion, Harvey, Reno, and McPherson counties.

The Upper Permian Formations

Marion

The upper fossiliferous strata of the Permian consist of thin buff limestones, shales and marls, containing in places beds of gypsum and salt. These strata have been described by the writer under the name Marion formation (Chas. S. Prosser, Journal Geology, vol. III, November 1895, p. 786) for which Professor Cragin, later proposed the name Geuda salt measures (F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, vol. VI, March, 1896, pp, 3, 9), but which, however, he subsequently withdrew in favor of the prior name of Marion (American Geologist, vol. XVIII, August, 1896, p. 131). This is the highest formation of the Kansas Permian in which fossils have yet been found, and paleontologically the upper limit of the formation may be considered as defined by the disappearance of fossils. Only in the lower part of the formation have any Brachiopods been found, and then simply the one species, Derbya multistriata (M. & H.) Pros., the majority of the species being rather small Lamellibranchs characteristic of the Permian [Professor Cragin reports Athyris subtilita in the Marion in southern Kansas (see Colorado College Studies, vol. VI, p. 13)]. The most abundant species are:

Pleurophorus subcuneatus M. & H.

Pseudomonotis Hawni M. & H.

Myalina permiana (Swallow) M. & H.

Bakevellia parva M. & H.

all of which are typical Permian species. From this formation the author has identified the following species:

- Pleurophorus subcuneatus M. & H.

- Pleurophorus subcostatus M. & W.

- Bakevellia parva M. & H.

- Yoldia subscitula M. & H.

- Macrochilina cf. angulifera White.

- Nautilus eccentricus M. & H.

- Schizodus curtus M. & W.

- Schizodus ovatus M. & H.

- Dentalium Meekianum Geinitz (?)

- Aviculopecten occidentalis (Sheem.) Meek.

- Myalina permiana (Swal.) M. & H.

- Pseudomonotis Hawni M. & H.

- Pseudomonotis Hawni M. & H. var. ovata M. & H.

- Pseudomonotis cf. variabilis Swal.

- Nuculana bellistriata Stevens var. attenuata Meek.

- Derbya multistriata M. & H. Pros. (?)

- Septopora biserialis (Swal.) Waagen (?)

- Edmondia Calhouni M. & H.

- Nucula cf. Beyrichi v. Schauroth; also cf. N. parva McChesney

- Small Gastropod cf. Aclis Swalloviana (Geinitz) Meek

From the buff limestones and shales in a small quarry on the south bank of the Smoky Hill river, south of Abilene and not much below a conglomerate exposed along Turkey creek which was first described by Meek and Hayden in 1859 (Proceedings Academy Natural Science, Philadelphia, Vol. IX, p. 16, No. 9), the writer collected the following species (see Journal Geology, Vol. III, p. 788):

| 1. Pleurophorus subcuneatus M. & H. | a | |

| 2. Bakevellia parva M. & H. | e | |

| 3. Edmondia Calhouni M. & H. (?) | c | |

| 4. Yoldia subscitula M. & H. | u | |

| 5. Schizodus curtus M. & W. (?) | u | |

| 6. Nucula cf. Beyrichi v. Schauroth ; also cf. N. parva, McChesney | a | |

| 7. Aviculopecten (?) sp. | (Very imperfectly preserved) | u |

| 8. Septopora (?) sp. | u | |

| 9. Small Gastropod cf. Aclis Swalloviana (Geinitz) Meek | r | |

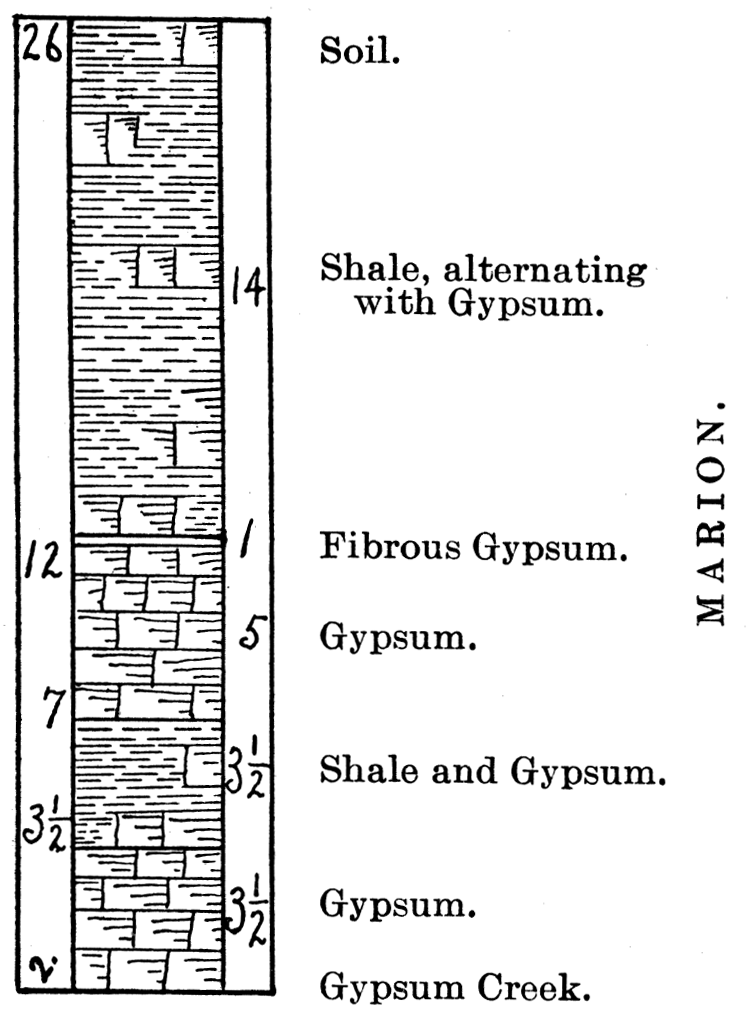

The bluffs on the southern bank of the Smoky Hill river from Abilene to Salina are comparatively low with but few outcrops. On the east bank of Gypsum creek at its mouth twelve miles west of Turkey creek, or eleven miles west of the fossiliferous limestone in the quarry south of Abilene, is the Merrill gypsum quarry and mill. The section of the bank of the creek bluff at the Merrill quarry is as follows:

| Section of the Merrill Gypsum Quarry | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Feet | |

| 6. | Soil | |

| 5. | Yellowish and bluish shales alternating with thin layers of gypsum | 14 - 26 |

| 4. | Thin layer of fibrous gypsum (1 or 2 inches) |

- 12 |

| 3. | Massive snowy gypsum (the principal quarry stratum |

5 - 12 |

| 2. | Mainly shales | 3 1/2 - 7 |

| 1. | Gypsum to level of Gypsum creek | 3 1/2 - 3 1/2 |

Figure 2—Merrill Quarry Section, five miles East of Salina.

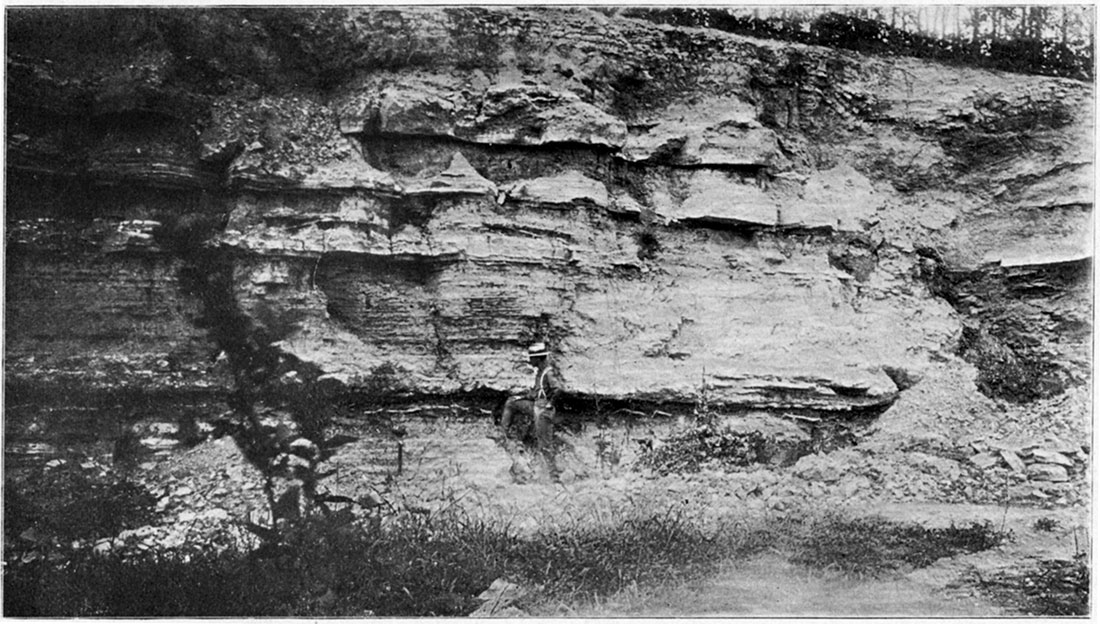

Plate XI gives a clear idea of the exposure of rocks at the above quarry. Mr. Beede's foot rests on top of the massive stratum of gypsum—No. 3 of the section—only part of which is shown in the picture. Above this are the 14 feet of alternating layers of shales and gypsum—No. 5—capped by the soil. The rock dips slightly to the north and east while several small rolls are shown along the side of the bluff. Doctor Grimsley in describing the gypsum deposits of Kansas has correctly referred the gypsum of central Kansas to the Marion formation (G. P. Grimsley, American Geologist, Vol. XVIII, October 1896, p. 237).

Plate XI—Merrill Gypsum Quarry, on Gypsum Creek, Marion Formation, Saline County. (Photographed by Prosser, 1896.)

Three miles west of Gypsum creek and seven miles east of Salina, on the southwest quarter of section 7, Solomon township, is a small excavation known as Benfield quarry. The locality is 100 feet above the Gypsum creek level, though probably not stratigraphically as much as that above the gypsum, on account of the easterly dip. In the bottom of the quarry is a stratum of massive limestone, hard and quite durable, containing fragments of a few shells, probably Nuculas. Above this are about 10 feet of thin, buff to yellowish shales, mostly soft, though some of the layers are hard and distinctly laminated. Part of the shales are covered with dendritic markings which are common on many of the Upper Permian shales.

About five miles west of the Benfield quarry, and perhaps a little lower, Professor Cragin reports an abandoned quarry, the upper stratum of which is a 10 inch "bastard limestone" that was used in the early settlement of Salina for walling wells, etc. Upon this limestone stratum it is reported that reptilian footprints were noticed some years since (F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, Vol. VI, p. 13.), though there seems to be no well authenticated record of the correctness of this determination.

On the east side of East Dry creek, in the southern part of section 21, Greeley township, three miles southeast of Salina is a small quarry, at the bottom of which, now nearly covered, are thin brownish yellow limestones with blackish specks, which contain fossils that are the typical small Lamellibranchs of the Marion, and the following species were obtained:

| 1. Myalina perattenuata M. & H. | r |

| 2. Pleurophorus subcuneatus M. & H. | c |

| 3. Bakevellia parva M. & H. | r |

| 4. Small Lamellibranch; somewhat like Pleurophorus, possibly Edmondia or Schizodus | a |

In that vicinity a number of loose pieces of the Marion or a very, similar limestone were noticed containing specimens of Bakevellia parva M. & H. Above the limestone are creamy to buff colored shales with reticulated or dendritic markings, 6 feet thick, covered by 3 feet of soil.

Three miles south and two miles east of Salina, on the eastern bank of the Smoky Hill river, on the southwest quarter of section 29, Greeley township, is the Bacott quarry, in which a stratum of limestone 1 1/2 feet thick has been worked to quite an extent for com. mon building stone. The exposures along the bank of the river show slight rolls, the rocks being folded into gentle anticlines and synclines. In one place there is quite a sharp dip to the south amounting to 8 feet in a short distance, when the dip turns to west of north.

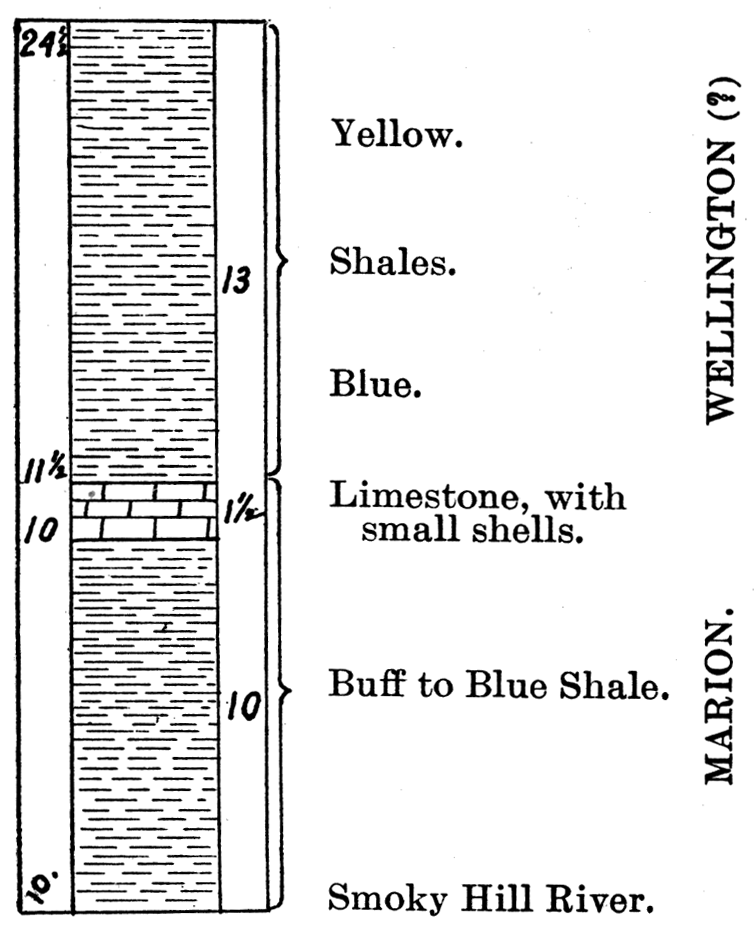

| Section of Bacott Quarry | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Feet | |

| 5. | Soil | |

| 4. | Yellowish shales on top containing a layer of flint 1 inch thick. Blue shales in lower part. | 13 - 24 1/2 |

| 3. | Massive limestone of quarry containing small fragments of shells | 1 1/2 - 11 1/2 |

| 2. | Drab hard limestones containing abundant specimens of Myalina perattenuata M. & H. 1 inch thick. | - 10 |

| 1. | Buff and bluish shales to the level of the Smoky Hill river | 10 - 10 |

Figure 3—Section of Bacott Quarry, South of Salina.

From this quarry the following species were collected:

| 1. Myalina perattenuata M. & H. | aa |

| 2. Myalina permiana (Swallow) M. & H. | u |

| 3. Pleurophorus subcuneatus M. & H. | c |

| 4. Bakevellia parva M. & H. | u |

| 5. Small Lamellibranch same as in the quarry on section 21, Greeley township | c |

According to Prof. A. W. Jones of Salina—to whom the writer is indebted for many favors—at about the level of the river is a stratum of gypsum about 10 feet below the base of the limestone—No. 3 of the above section. A shaft sent to the depth of 25 feet is reported to have penetrated principally gypsum. Professor Cragin has briefly described this locality, noting the layer with abundant Myalinas, which he called M. permiana, and named the gypsum stratum the Greeley gypsum (F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, Vol. VI, n. 10). The writer agrees with Professor Cragin in regarding the fossiliferous limestones in this quarry as near the top of the Marion formation.

No other outcrops of the Marion were studied in the valley of the Smoky Hill river, and these limestones according to Professor Jones do not extend much farther up the river valley (F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, Vol. VI, n. 10, p. 10, where Prof. Jones is the authority for the statement "that the most southerly appearance of these limestones and shales on the Smoky is about four and a half miles south of Salina."). The southeastern part of Saline County and southwestern portion of Dickinson below the base of the Cretaceous are variously colored argillaceous shales which have been referred to the Wellington. Farther south in the western part of Marion County on the head waters of the Cottonwood river occur the buff, thin limestones of the Marion formation, containing specimens of Bakevellia parva M. & H. with a few other fossils typical of the upper rocks of this formation. They were noticed especially in Lehigh and West Branch townships, and west of these limestones is the deposit of sand of varying thickness, the eastern border of which crosses the western tier of townships in Marion County.

The fauna and lithologic characters of the Marion formation in Marion and Butler counties were described by the author in his paper defining this formation, to which the reader interested, in the details is referred (Chas. S. Prosser, Journal Geology, Vol. III, p. 786). Farther south in Cowley County it was found that, in general, the distinctive features of the formation as noted in the eastern central part of the state remain constant. The base of the formation is well shown along the bluffs of the Walnut river in the western part of the county. Capping the bluffs along both sides of the river in the vicinity of Winfield are numerous exposures of a rough, heavy limestone which frequently contains large iron-stained concretions in which are a few fossils, as Productus semireticulatus (Martin) de Koninck, and these concretions are termed in that locality "sand bricks" (on the authority of Mr. C. N. Gould). This is the same limestone that is prominently exposed in the vicinity of the cities of Marion and Burns in Marion County regarded by the writer as the top beds of the Chase formation. On account of its conspicuous occurrence in the vicinity of the city of Marion, the writer first called it the "Marion concretionary limestone" (Journal of Geology, Vol. III, pp. 772, 797). Although the name was never intended in any sense as a formation name, objection has been made to its use because it is not included in the Marion formation, consequently, in order to avoid confusion, it is considered better to withdraw the former name, and on account of the characteristic exposures in the vicinity of Winfield to substitute the term Winfield concretionary limestone. Again objection is made to the use of a name for a bed, zone or any subdivision of a formation differing from the name used for that formation. In respect to this criticism it is only necessary to say that such usage is well established in geological classification and is of decided assistance in referring briefly to certain local characters, or minor divisions of a formation to which it would be undesirable to give the rank of a formation. The classic state in American stratigraphic geology affords numerous illustrations of this usage as, for example, the Moscow and Ludlowville shales of the Hamilton formation, and the Cashaqua and Gardeau shales of the Portage formation. This custom seems to be sufficiently sanctioned by its use in such standard works as Dana's Manual and Geikies' Text-Book of Geology.

Five miles north of Winfield, in the southwest corner of Fair View township at the head of a small arroyo is an excellent exposure of this prominent Winfield limestone, in which the concretions are numerous and exactly the same in character as in this stratum farther north in Marion County. This limestone forms a marked escarpment along the side of the bluff west of the Walnut river at Winfield where it has a thickness of 13 feet. It caps the high points to the east of the river at Winfield, as, for example, on the Asylum reservoir and College hills, where the ledge is some 80 feet higher than in the escarpment of the river, indicating a dip of about forty feet per mile to the west across the valley of the Walnut river at Winfield. The line of division between the Chase and Marion formations in the western part of Cowley County, follows the Walnut river valley for the greater part of the distance across the county. Apparently this same limestone is quarried on the eastern bank of the Walnut river east of Arkansas City, though at this locality above the 11 feet of massive limestone are shaly layers containing abundant fossils, but no concretions were seen.

On the eastern side of the Arkansas river and canal, two and one half miles northwest of Arkansas City, is a buff soft limestone, 15 feet thick, covered by 7 feet of yellowish shales. In the limestone beds is a cellular layer containing specimens of Bakevellia parva, M. & H.&typical thin-bedded Marion limestone.

About Geuda Springs, seven and one half miles northwest of Arkansas City, are outcrops of yellowish shales and coarse, cellular rock, some of it brownish-red to iron color&due probably to the presence of iron. No fossils were found in the rocks at this vicinity, nor west of that town in the Marion. At this locality are mineral springs, while along the valley of Salt Creek above and below the springs is an incrustation of salt. The porous rocks in this part of the Marion formation have been shown by other writers to contain the thick beds of rock salt of southern and central Kansas (Robert Hay, Seventh Biennial Report Kansas State Board of Agriculture, 1891, pt. II, p. 83. Eighth Biennial Report Kansas State Board of Agriculture, pt. II, p. 105. F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, Vol. VI, 1896, p. 9). This has been recently very clearly stated by Professor Haworth as follows: "Well records have been obtained from many different parts of the salt region which, when drawn to scale and compared, show very conclusively that the salt beds lie above the heavy limestone beds, and below a bed of blue shale which in turn is below the 'Red-beds.' As the blue shales so well developed in Sumner County and adjacent territory underlie the 'Red-beds,' and as the latter are admitted to be the first above the Permian, it follows that the blue shales are Permian. But as the salt beds are below the blue shales, which approximate 300 feet in thickness, they are well within the Permian." [University Geological Survey of Kansas, Vol. I, 1896, p. 191.] For these salt and gypsum bearing rocks, evidently a portion of the salt bearing beds being in the vicinity of Geuda Springs, Professor Cragin proposed the name "Geuda salt-measures," which, later he withdrew in favor of the prior name Marion formation, as already stated.

In the Anthony well, in Harper County, 404 feet of rocks have been referred to the "salt beds" (University Geological Survey of Kansas, Vol. I, 1896, Pt. XXI), though in the well section it would probably be a difficult matter to determine the exact line of division between the Marion and Chase formations. Professor Cragin has estimated that "the thickness of the outcrops probably varies from 300 to 400 feet" and has concluded that the dip "in southern Kansas is southward and westward." [F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, Vol. VI, p. 15.]

No attempt was made to trace the line of division between the Marion and Wellington formations across Sumner County which if accurately done would be an undertaking of some difficulty on account of the level nature of the county and the gradual transition from the lower to the higher formation.

Wellington

It will be, perhaps, a somewhat difficult matter to draw a line of separation sufficiently sharp for the purposes of areal geology between the Marion formation and the overlying gray, reddish and greenish argillaceous shales. However, the two negative characters, absence of fossils together with the general absence of limestones, may serve as a means of identifying the formation. It is probable that careful search will eventually reveal a few fossils, the number probably always remaining small, in some part of these shales. On the lithologic side, though the formation contains some calcareous layers and a larger amount of red shales, perhaps Professor Cragin's characterization of these rocks as "essentially a thick body of blue-gray and slate-colored shales" (F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, Vol. VI, p. 17) will serve as a satisfactory description of the formation. Professor Cragin has proposed the name Wellington shales (F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, Vol. VI, pp. 3 and 16) for the above formation, upon which is located the city of Wellington, the county seat of Sumner County. In Saline County there are probably 200 feet of the Wellington shales, but in the southern part of the state they attain a thickness of more than twice that amount. [Professor Cragin gives 255 feet for the Wellington beneath Ellsworth, in the first county west of Saline (Colorado College Studies, Vol. VI, p. 16).] The greatest reported thickness of these shales is in the well section at Caldwell in the southwestern part of Sumner County, which according to Professor Cragin is 445 feet (Colorado College Studies, Vol. VI, p. 16); while in the Anthony well in Harper County, twenty five miles northwest of Caldwell, a mass of blue shales, referred to the Wellington by Professor Cragin, has a thickness of 395 feet (University Geological Survey of Kansas, Vol. I, pl. XXI; F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, Vol. VI, p. 17), The author first studied the upper part of this Kansas Permian in Marion County where these shales are much thinner, and in the description of that part of the state included them in the Marion formation (Journal Geology, Vol. III, p. 786 and 797). However after studying them as exposed in their typical region in Sumner County, the writer is inclined to follow Professor Cragin and assign to them the rank of a formation.

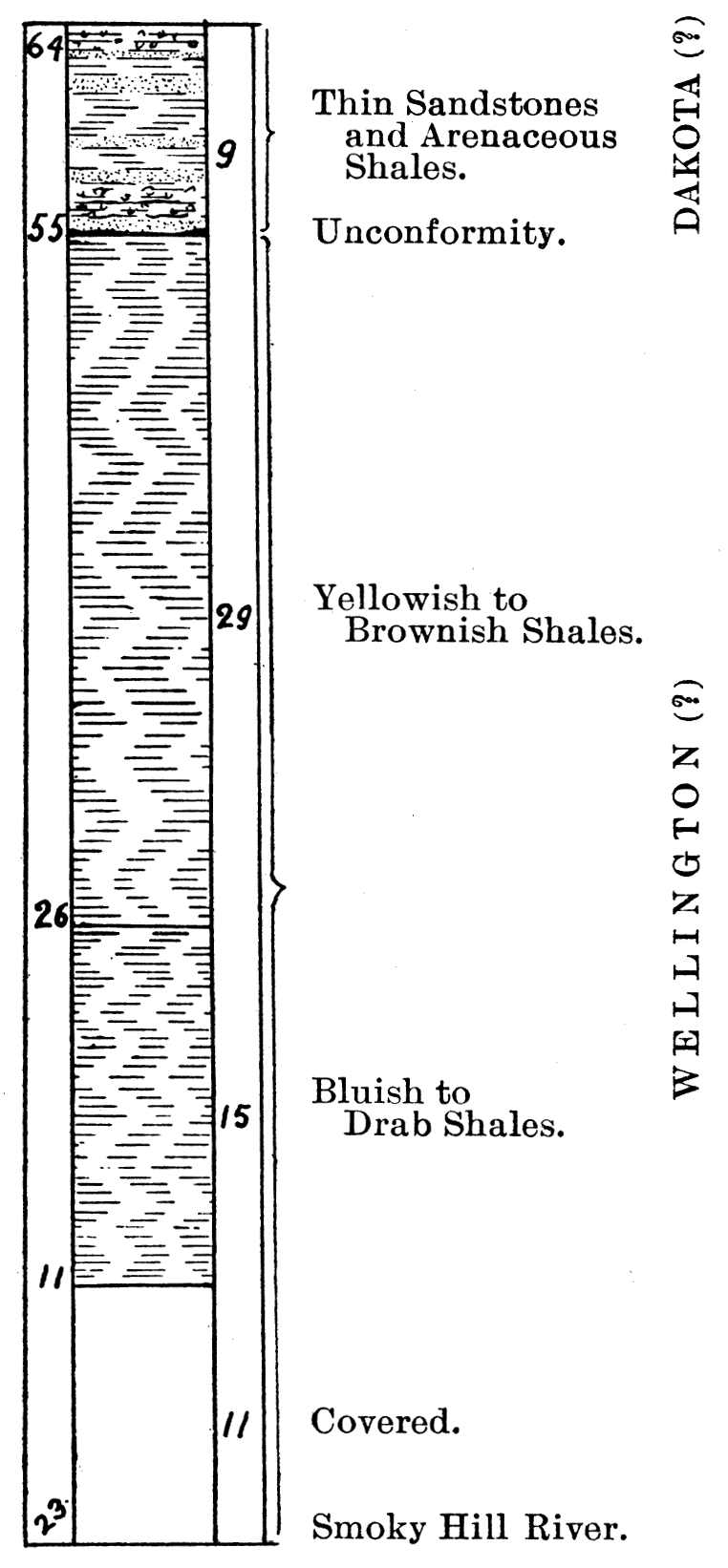

In Saline County the base of the Cretaceous, which is the Kiowa shales, Mentor beds, or Dakota sandstone, rests on the Wellington whose upper surface is apparently irregular indicating a period of elevation during which its surface underwent extensive erosion before the deposition of the Cretaceous. This is well shown by various sections in Saline County, a few of which will now be described.

Figure 4—Section at Smoky Hill Mill, one mile southeast of Salina.

Figure 5—Section three and one-half miles East of Mentor.

| Section of the Bluff east of the Smoky Hill River, at the Upper Smoky Hill Hill, one mile southeast of Salina | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Feet | |

| 4. | Capping the small buttes is a coarse-grained, massive brownish-gray sandstone, containing dark brownish-red concretions. Thin sandstones and arenaceous shales, partly brownish-gray in color. At base a massive sandstone that rests directly on the shales, but apparently unconformably. Base of the Cretaceous, probably Dakota. |

9-64 |

| 3. | Yellowish to brownish and buff soft argillaceous shales. | 29-55 |

| 2. | Bluish to drab shales that weather to a buff color—thin and somewhat laminated. | 15-26 |

| 1. | Covered. A little farther up the river the blue shales show to the water level. | 11-11 |

| Level of the Smoky Hill river. [Prof. Robt. Hay called this hill Dakota with Permo-Carboniferous shales at the base (Transactions Kansas Academy Science, Vol. IX, 1885, p, 112).] | ||

No fossils were found in the rocks composing the above section, although careful search was made for them. Nos. 1, 2 and 3 have been referred provisionally to the Wellington, simply on account of the absence of fossils and their lithologic characters. Two miles farther up the river is the Bacott quarry with the Marion fossils, and on the hill two and one half miles southeast of the river bluff section, in section 21 Greeley township, buff limestones with Bakevellias were found at an elevation near that of the shales in No. 3 of the section. It seems probable that the small anticlinal fold noted in the Bacott quarry has brought up the top of the Marion at that locality, so that lower rocks are exposed than in the section at the mill.

Six miles south of Salina and the Upper Mill section on the Smoky Hill river is the small village of Mentor in Walnut township. A section east of Mentor was measured from the river level past the Berwick school house to the top of the ridge two and a quarter miles east of the river. This is the typical locality of the "Mentor beds" of Professor Cragin which will be discussed later.

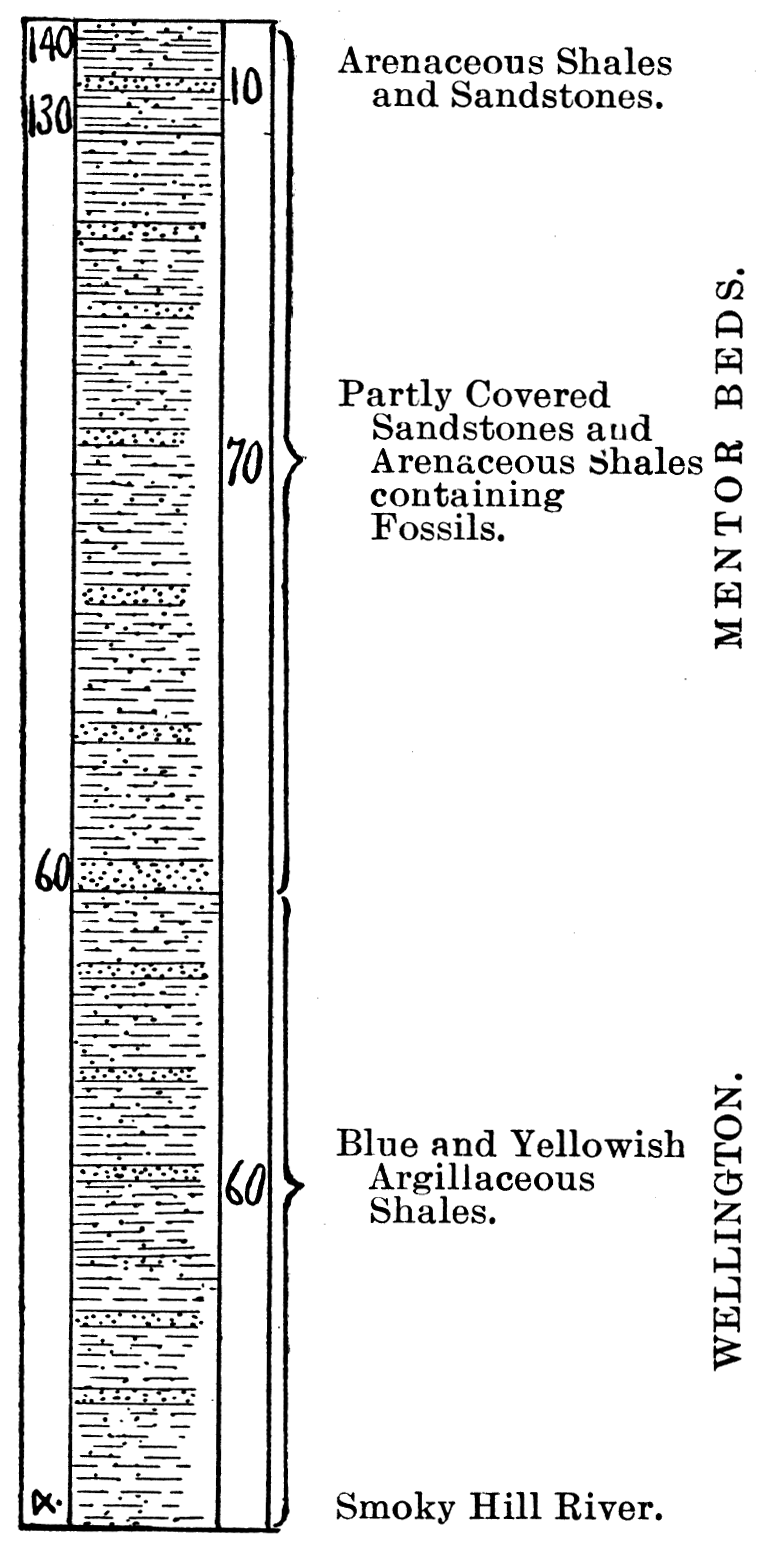

| The Mentor Section | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Feet | |

| 3. | Mostly covered; but apparently a brownish sandstone similar to that below. | 10-140 |

| 2. | Iron brown sandstone exposed at intervals along the roadside and in the field. Three quarters of a mile east of Berwick school house. Partly covered. In layers are abundant fossils. Apparently the base of the Mentor. | 70-130 |

| 1. | Yellowish and bluish argillaceous shales, with some red streaks. Wellington. | 60-60 |

| Level of Smoky Hill river. | ||

Two miles directly south of the four corners, one mile east of the Berwick school house, is a most interesting exposure of the Permian and Cretaceous line of contact. The rocks show along the highway at the southwest corner of section 27 Walnut township, and in the field in the southeast corner of section 28. The section is as follows:

| 3. | Brownish, iron sta.ined sandstone containing Mentor fossils. |

| 2. | Slightly pinkish shell limestone 1 foot thick, containing abundant specimens of Ostrea. Kiowa. |

| 1. | Yellowish argillaceous shales immediately below the limestone. Similar blue, yellowish and slightly reddish shales continue from 150 to 160 feet to the level of the Smoky Hill river. Wellington. |

It will be noticed on comparing the two sections just given, that in the Mentor, the base of the Mentor beds is approximately 60 feet above the river level; while in the second section, only two miles south, the base of the Kiowa is from 150 to 160 feet above the river level, or from 90 to 100 feet higher than in the Mentor section. The uncertainty as to the exact base of the Mentor beds in the Mentor section may reduce this difference somewhat, still there will be a decided discrepancy between them which is not explained by folding or dip. The floor upon which the Cretaceous was deposited was evidently a decidedly uneven one.

On the western side of the Smoky Hill river these shales are developed to a greater thickness than on the eastern, Professor Cragin has identified them as belonging to the Wellington, stating that they occur at intervals in the foot of the bluffs of Spring creek from Salina to a point in the southwest vicinity of Bavaria (F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, Vol. VI, p. 17). The Wellington shales were noted at a number of exposures from Bavaria to the vicinity of the summit of the ridge three miles south, but only a number of short sections were found. One mile southwest of Bavaria on the Spring Creek bluff are yellowish shales similar to those of No. 3 in the Upper Mill section southeast of Salina. About one and one fourth miles southwest of the above locality is another fairly good exposure on the banks of a small pond, in the southern part of section 4 Washington township. This shows some 15 feet of argillaceous, unfossiliferous shales, the lower and greater portion of which are thin, yellowish and bluish, and above these are some harder and thicker layers capped by 2 feet of red shales.

Near the summit of the ridge three miles south and one half mile west of Bavaria, in the southwest corner of section 10, Washington township, Mentor fossils were found in the brown iron colored rock on top of the yellowish Wellington shales. The base of the Mentor at this locality is from 160 to 170 feet above the Smoky Hill river level, nine and one half miles directly east. One mile south of the locality just described, four miles west of Smolan and eleven and three fourths miles west of the Berwick school house Mentor beds, on the roadside at the northwest corner of section 22 Washington township, is an excellent exposure of the brownish-red very fossiliferous Mentor beds. A little below are yellowish, argillaceous shales, which according to Mr. Beede are shown for some 50 feet in the well in the draw just south. This exposure is fully 150 feet above the Smoky Hill river, 10 miles directly east. Professor Udden concluded that the Dakota in Saline County dipped 8 feet per mile to the east (American Geologist, Vol. VII, June 1891, p. 344). A dip at this rate to the east would carry the outcrop of the Mentor beds four miles west of Smolan, down to only 66 feet above the river level on the hill east of Berwick schoolhouse. It will be remembered that in the section of that hill the approximate base of the Mentor beds is given as 60 feet.

Six miles south of the above locality, at Falun, are two buttes capped by brownish-red sandstone containing fragments of parallel and netted veined leaves, apparently Dakota species. Below, from wells and exposures by the roadside are bluish and yellowish shales, some of which are rather coarse and contain gypsum of the Wellington. The base of the Cretaceous on these buttes is about 1370 feet A. T., or approximately the same as at the Mentor locality six miles north. The Wellington shales are quite well shown around the northern end of the Smoky Hill Buttes .where their top is about 1360 feet A. T.

Professor Udden has indicated a Pleistocene deposit that covers the central part of McPherson County and extends north along the valley of the Smoky Hill river to the vicinity of Salina. This deposit contains bones of Myalonyx Leidyi Lindahl, Equers Major De Kay and some fresh water shells (American Geologist, Vol. VII, June, 1891, pp. 340-345. See especially the map on p. 340.).

The streams and arroyos of the adjoining corners of Saline, Dickinson, Marion and McPherson counties revealed numerous exposures of bluish, yellowish and slightly reddish shales which were generally regarded as belonging in the Wellington. These are apparently the same as the shales noted by Doctor Sharpe as extending from the middle of Marion County to north of Smoky Hill river, though I do not agree with the statement that they are "principally red in color" (University Geological Survey of Kansas, 1895, Vol. I, p. 191).

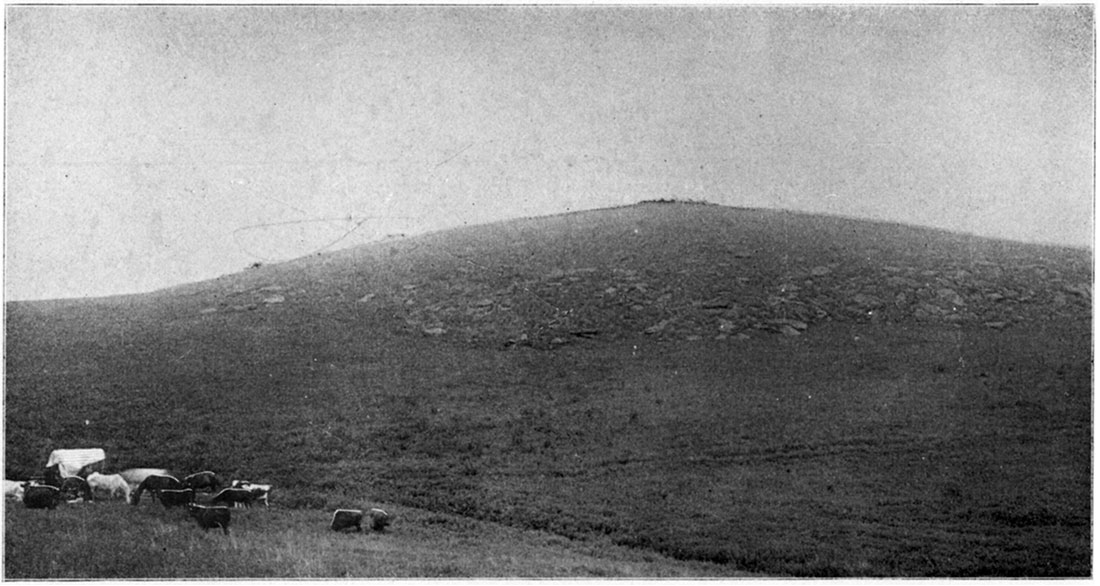

The vein of the Dakota sandstone on top of Twin Hill, Plate XII, represents one of the Twin Hills in Delmore township, capped by massive Dakota sandstone. The slope of the hill is covered with large blocks of the sandstone which have fallen from a former larger cap of the sandstone than the one that now remains on top of the hill.

Plate XII—Dakota Sandstone on top of Twin Hill, McPherson County. (Photographed by Prosser, 1896.)

In Sumner County, in the southern tier of counties these shales attain their greatest known thickness and cover the greater part of that county. On account of the very level nature of this county there are no exposures of any considerable thickness, though small outcrops along the streams and in the steeper parts of the low hills are not of infrequent occurrence. Slate creek, which flows diagonally across the county from the northwest corner to near the south, east portion, affords many small exposures of these shales. The prevailing colors of these shales are yellowish to bluish and grayish tints with greenish and reddish bands of some thickness. There are also occasional thin layers of limestone not unlike some of the thin limestones in the upper Marion. They may be distinguished, however, from the underlying Marion by the general absence of limestones, being composed principally of argillaceous shales; and from the overlying Marion by their general grayish or bluish color which is in strong contrast with the prevailing red color of that formation.

Professor Hay in his paper on the "Geology of Kansas Salt" noted the occurrence of "between one and two hundred feet of gray shales, with an occasional limestone stratum." [Robert Hay, Seventh Biennial Report Kansas State Board of Agriculture, Pt. II, p. 87, Topeka. See also Fig. I "Generalized section from Geuda Springs to Kingman" on p. 86, and Fig. III, "Generalized section across Kansas" on both of which the "gray shales" are represented between the "Salt measures" and the "red beds."] However, as already stated, Professor Cragin is the first one to accurately describe the lithologic characters of these rocks and to propose an appropriate formation name for them.

By the roadside on the Oxford-Wellington road four miles, east of Wellington are yellowish thin limestones that alternate with yellowish shales, the lithologic character of these rocks differing but slightly from that of some of the Marion. Toward the top of the ridge are greenish argillaceous shales, and with them are layers of yellowish shales in which are layers of small, somewhat flattened concretions, The concentric structure of some of these concretions is nicely shown. Professor Hay has described these layers as similar "to a pan of biscuits" and states that they will "separate into several thin concentric domes as would the layers of half an onion." [Robt. Hay, Bulletin U. S. Geological Survey, No. 57, pp. 19, 20, Washington, 1890. See fig. 2, on p. 20.] He apparently failed to recognize their concretionary character.

From the above locality along the road toward Wellington are occasional outcrops of yellowish and bluish, soft argillaceous shales, with an occasional layer of harder material an inch or so in thickness. Similar shales show in a branch of Slate creek just east of the. city, and along the side of the hill to the west of Slate creek and the city. The blue shales are especially well shown in a small creek on the upland west of Slate creek and 75 feet above it, along the Southern Kansas railroad.

In the vicinity of Wellington is an extensive deposit of gravel and sand which was referred to the Champlain period by J. P. West, and which Professor Cope calls "the Pleistocene sands." [Robt. Hay, Bulletin U. S. Geological Survey, No. 57, pp. 39, 40. See Fig. 19, p. 40, which gives a section of the Santa Fe railway cut at Wellington. See Judge West's article in Kansas City Review of Science and Industry, February 1895. This stratified deposit of sand and gravel was also referred to the Champlain by Professor Cragin who mentioned the occurrence of Mastodon Elephas and Bos latifrons in it (Bulletin Washburn College Laboratory Natural History, April 1895, p. 85, Topeka).] [Proceedings Academy Natural Science, Philadelphia, Pt. I, January-April 1894, pp. 67, 68.] This identification is not simply conjecture, for from an abandoned sand quarry to the west of the city vertebrate fossils have been obtained which Professor Cope identified as Elephas primigenius and Bos crampianus Cope (Proceedings Academy Natural Science, Philadelphia, Pt. I, January-April 1894, p. 68 and Journal Academy Natural Science, Philadelphia, Vol. IX, pt. 4, 1895, pp. 453, 456.). From the sand quarry on the eastern side of Wellington, Professor Cope identified a posterior molar of Elephas primigenius.

On the creek a short distance west of Mayfield is bluish sandy shale in places, while the Roil is decidedly red, probably colored by leaching from the Red-Beds to the northwest. On a small branch of Beaver creek, one mile north and three miles east of Milan (northwest quarter section 14, Ryan township) is an exposure of a few feet of the Wellington shales.

| Section three miles east of Milan | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Feet | |

| 4. | Soil | |

| 3. | Greenish argillaceous shales | 2-5 1/2 |

| 2. | Maroon argillaceous shales | 2-3 1/2 |

| 1. | Blue argillaceous shales to the creek level. | 1 1/2-1 1/2 |

| The shales of the lower part are thicker, light gray in color and contain small quantities of Malachite. | ||

On the road one fourth mile west of Beaver creek are red somewhat sandy shales, similar to those seen on the ridge east of the creek. Along Shore creek to the west of Milan are reddish, rather sandy deposits regarded as in the lower part of the well known Red-Beds, the lower part of which Professor Cragin has called the Harper sandstone. This opinion agrees with an early one held by Professor Cragin; for in 1885 he said that west of Wellington he first saw "the red sandstone of the Dakota [as he then called the Red-beds] at Milan. It also appears at certain points in the Chikaskia river" (F. W. Cragin, Bulletin Washburn College Laboratory Natural History, Vol. 1, April 1895, p. 86, Topeka.). Mr. Adams also spoke of Argonia in the Chikaskia river as the eastern limit of the Red-Beds (University Geological Survey, Kansas, Vol. I, p. 29). From this locality westward toward Argonia and the Chikaskia there are not infrequent outcrops of the red rocks, though a large part of the country in the broad valley, of the Chikaskia river and its branches is covered by beds of loose sand so that the underlying rocks are concealed. This loose sand forms dunes along the banks of the streams, and is probably an alluvial formation as suggested by Professor Hay. [The Professor said "on the west line of Sumner Co. the Carboniferous (in which he includes the Wellington) . . . disappears under the extensive sands of the Chikaskia, whose broad valley is a mere depression in the high prairie. This concealment by alluvial deposits is very extensive both south and north" (ibid., p. 20); also see p. 43 where he speaks of the "immense beds of sand in the valleys of the Chikaskia, the Medicine," etc. As shown on his "Geologic Map of Southwestern Kansas" quite a large area in the western part of Sumner County and eastern part of Harper County to the south of the Chikaskia river is mapped as covered by Pleistocene sand.]

The Cimarron Series or the Red-Beds

Historical Review

Succeeding the Wellington formation is a great mass of rocks composed essentially of soft, friable, sandstones and argillaceous shales. The prevailing color is red and this series of rocks has generally been called the Red-Beds. The name refers of course to the prevailing color similar to that of the rocks of northern Texas and Oklahoma which are also known by the general name of Red-Beds.

In Kansas in the upper part of the series are thin layers of gypsum, and at one horizon is a deposit from 25 to 50 feet in thickness of massive gypsum. Thin layers of gray to greenish gray sandstone also occur occasionally, but are neither of sufficient thickness nor frequency to affect the general descriptive term of Red-Beds.

On the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe railway running from Winfield to Medicine Lodge this series is first seen in the vicinity of Mayfield and Milan. So far as determined, the base of the Red-Beds rests conformably on the Wellington formation. The line of separation has been traced to some extent and indicated on the geological map as crossing irregularly the western part of Sumner, eastern Kingman, western Sedgwick and eastern Reno counties, to the valley of the Arkansas river. The top of the series is determined on the west and north by either the base of the Comanche series or the Tertiary where the Comanche is wanting. The series has a thickness of perhaps 1200 feet, determined partly from well sections and partly from surface exposures.

In correlating this mass of rocks investigators have referred them to several systems and a brief review of such correlation may be of interest.

On the geological map of Kansas published by Professor Mudge in 1878 (First Biennial Report State Board of Agriculture of Kansas, 2nd ed. p. 47), the greater part of the area south of the Arkansas river, now known to belong to the Red Beds, is represented as of upper Carboniferous age though it is stated in the text that west of Harper the region has been little examined by himself or others "but appears to be represented by the Fort Benton and Dakota groups" (First Biennial Report State Board of Agriculture of Kansas, 2nd ed. p. 55). This does not agree with the map, for Barber, Comanche and the southeastern part of Clark County, to the west of Harper, are colored as belonging to the upper Carboniferous.

The next paper of importance bearing upon this region is the "Sketch of the Geology of Kansas" by Professor St. John in 1883. On the "Geological map of Kansas" in this report (Third Biennial Report State Board Agriculture of Kansas, op. p. 575), the line separating the Cretaceous and Upper Coal Measures south of the Arkansas river, is represented as crossing central Reno, eastern Kingman and Harper counties. In the text of this report, the Dakota formation of the lower Cretaceous is fairly well described, and the Red Beds are provisionally correlated with it. Prof. St. John says "In the region south mid west of the Arkansas, the deep-red sandstones, presumably belonging to the same formation [Dakota], owing to their soft friable nature no longer afford prominent landmarks, though they still impress their presence upon the soil to which they have imparted its red color and loamy nature over a wide outlying belt immediately underlayed by the upper strata of the Upper Coal-Measures" (Third Biennial Report State Board Agriculture of Kansas, p. 589).

In 1885 Professor Cragin accepted St. John's correlation and gave some account of the extent of the series. Professor Cragin followed the line of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe railroad from Wellington to Medicine Lodge. "We come" he says "first upon the red sandstone of the Dakota at Milan. It also appears at certain points in the Chikaskia river. This is the main country rock westward to Medicine Lodge" (Bulletin Washburn College Laboratory Natural History, vol. I, p. 86, Topeka). The Gypsum Hills to the southwest of Medicine Lodge, were briefly described by Professor Cragin in this paper, where he stated that "The Gypsum Hills have their base of the Dakota sandstone. At their eastern outskirts, this formation includes their bulk, though even here they are capped by the Benton" (Bulletin Washburn College Laboratory Natural History, vol. I, p. 87, Topeka).

The following year Professor Cragin referred the great gypsum bed of Barber and Comanche counties to the Dakota formation, the upper part of which he regarded as probably formed by the variegated sandstone (Cheyenne sandstone) while "the overlying dark shales, from which the 'Black Hill' takes its name, [are] the base of the Benton" (Bulletin Washburn College Laboratory Natural History, vol. I, May 1886, p. 166, Topeka).

In 1887 Professor St. John published his "Notes on the Geology of Southwestern Kansas," in which the Red Beds were referred with a query to the Triassic, where they have generally been placed by subsequent writers. Professor St. John's explanation for this correlation is as follows: "The oldest geological deposits [of the district described by St. John in this paper] appear in the eastern portion of the district, and from their lithological appearance and stratigraphical relations to well-determined formations between which they occur, it is inferred they hold the position of the Triassic Red-Beds which are so well developed along the eastern foot of the Rocky mountains a few hundred miles to the west. . . . These deposits form the basis of the uplands in which the Medicine Lodge, in the vicinity of Lake City, . . . have eroded its bed to the depth of at least 150 feet. They also extend westward as far at least as Crooked creek, appearing lower and lower in the valley slopes until they pass beneath their beds as the declivity rises in that direction. East and south they compose the surface rocks in Barber and a large part of Harper County. The formation doubtless attains a thickness of 200 to 300 feet at least in this region, and its erosion by the numerous water-courses in the counties named has produced some of the most picturesque scenic effects to be found in the State." [Fifth Biennial Report Kansas State Board Agriculture, pt. II., pp. 140, 141.] Professor St. John was not successful in finding any fossils in the formation, which has been the experience of all subsequent investigators.

In 1889 Professor Hay, who has since so fully described the general appearance of the Red-Beds of southern Kansas, in a lecture before the Kansas Academy of Science, dwelt upon the extent of the area of the Red-Beds, which he described as thinning to the north, while the Dakota thins to the south. In reference to the age Professor Hay stated "These Red-Beds we call Triassic, but possibly the upper part may be Jurassic. As yet they have yielded no determined fossils in Kansas" (Robert Hay, Transactions Kansas Academy of Science, vol. XI., p. 36).

The same year, Professor Cragin changed his correlation of the Red-Beds from the Cretaceous to the Triassic. In his explanation of this change he "called attention to the similarity of the red beds of the Gypsum Hills to those of New Mexico, and deprecated the prevalent fashion of ignoring the claims, by earlier writers, that the Triassic existed in Kansas, since no evidence from fossils disputed such claims, and lithological evidence seemed to favor them. But later, in the article cited, he embraced the error, then current, of referring the red sandstones of southern Kansas to the Cretaceous. . . . The evidence of the Trias in Kansas, though based on lithological resemblances and assumed continuity of the Trias of New Mexico, etc., with occurrences in southern Kansas, is now generally regarded as all but conclusive. Yet the distinctly Permian affinities of the fossils from the lower red-beds of northern Texas and southern Indian Territory should at least make us very wary of assenting to any such thickness of the Triassic in Kansas ail that (1100 feet) ascribed to it by Mr. Hay." [Bulletin Washburn College Laboratory Natural History, vol. II., pp. 33, 34. Topeka.]

The first careful description of the Red-Beds was published by Professor Hay in 1890 under the heading "Jura-Trias." In describing the area of this terrane he gave it as "An extensive region, triangular in shape, whose northern apex is near the northern part of the great bend of the Arkansas river and whose base in Kansas runs on the southern boundary of the state from the ninety eighth to beyond the oue hundredth meridian, would be called by superficial observers the regions of red rock. The area of the formation expands across Indian Territory to the Red river and Texas. . . . If a descriptive name were wanted we should call it the Red Rock Formation. The whole country is red. The soil, even where it contains much carbonaceous matter, is ruddy, the sedentary soil, just forming on the steeper slopes is ruddier, flooded rivers glance in the sunlight like streams of blood, steep bluffs and sides of narrow canyons pain the eye with their sanguine glare". [Robt. Hay, Bulletin U. S. Geological Survey, No. 57, "A Geological Reconnaissance in Southwestern Kansas," pp. 20, 21, Washington.]

Professor Hay's evidence for correlating this terrane with the Jura-Trias seems to have been the appearance, lithological characters and stratigraphic position of the terrane. For after giving a summary of the evidence which he regarded as indicating such correlation he said "In brief, the lithologic characters, in so far as they may be regarded as criteria in the correlation of formations, and the stratigraphy alike suggest that the red rocks of southern Kansas represent the group of strata elsewhere found between the base of the Cretaceous and the summit of the Carboniferous; and although the evidence is not sufficient finally to demonstrate the age of the rocks, it is sufficient to warrant the provisional application to them of the name Triassic." [Robt. Hay, Bulletin U. S. Geological Survey, No. 57, "A Geological Reconnaissance in Southwestern Kansas," p. 25, Washington.]

On the "Geological Map of Southwest Kansas" accompanying this report the eastern line of the Jura-Trias is represented as crossing Reno, Sedgwick and Sumner counties, while the northwest boundary is represented as extending irregularly southwesterly from Reno across Kingman, Pratt, Barber, Kiowa, Comanche, Clark and Meade counties to the state line.

On the small geologic map of Kansas published by Doctor Williston in 1892 the Red-Beds are called Triassic, and their eastern line is represented as extending from the Arkansas river southeasterly across Reno, Kingman and Sumner counties. The northwestern boundary extends southwesterly from the Arkansas river across Reno, Kingman, Pratt, Barber, Comanche and Clark counties to the state line.

In 1893 Professor Hay changed his correlation of the Red-Beds from the Triassic to the Upper Permian of Kansas and assigned them a thickness of 900 feet (Robt. Hay, Eighth Biennial Report. Kansas State Board Agriculture, pt. II., p. 101). This change in correlation was due to the discovery of fossils in northern Texas in strata which were regarded as of the same general age as those of Kansas. Professor Hay said "The Texas geologists have considered the similar beds there as of Permian age; and Professor Cope, of Philadelphia, has shown me undoubted Permian fossils obtained from the Texas beds. This has led me to place them in the geological scheme as Permian. Still, in the Kansas beds no fossils have yet been found." [Robt. Hay, Eighth Biennial Report. Kansas State Board Agriculture, pt. II., p. 108.]

On the geologic map compiled by Mr. McGee, the Red-Beds are correlated with the Jura-Trias, and represented on the map as extending from northern Texas across Oklahoma into southern Kansas (Fourteenth Annual Report U. S. Geological Survey, pt. II., 1894, pl. II. Washington).

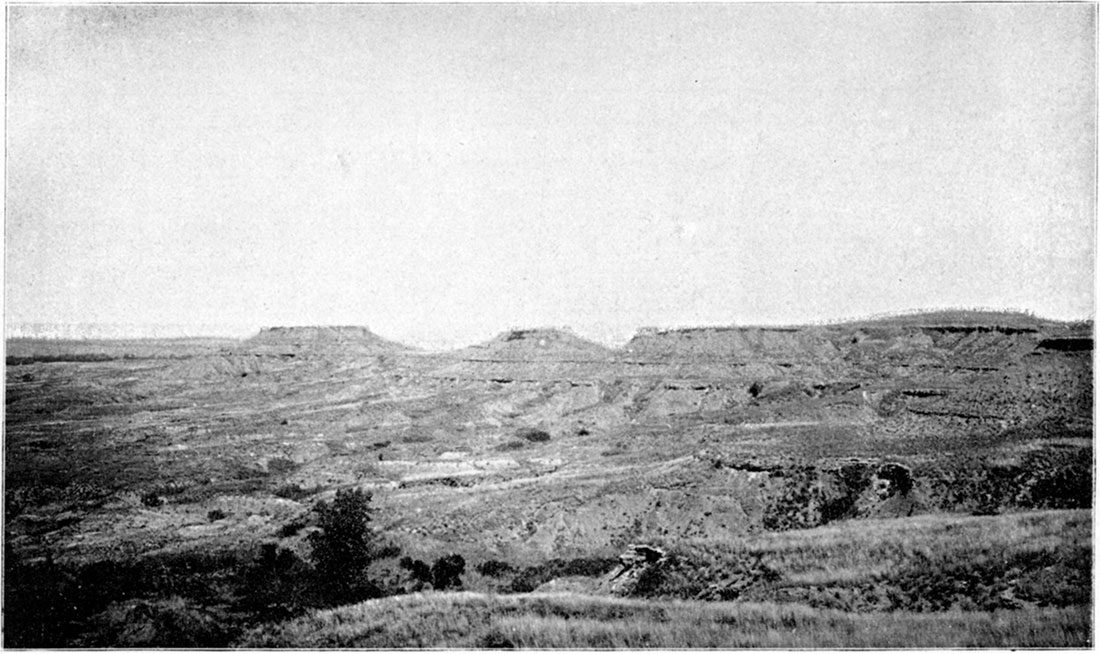

Plate XIII—Northern end of Gypsum Hills near Medicine Lodge (photograph by Prosser, 1896).

Professor Cope, who has thoroughly studied the vertebrate fossils of Texas visited in 1893 the Red-Beds of northern Oklahoma and southern Kansas. On account of the close connection existing between them, his statements in reference to their age are of great importance in correlating the Kansas terrane. He said "Our first object was to examine the red bluffs of Permian or Trias, which bound the canyons north and northwest of the post [Fort Supply in county "N" northern part of Oklahoma], which form part of the drainage system of the Cimarron. These bluffs we examined at various points and for considerable distances, but without obtaining any traces of fossil remains, excepting some fragments of wood. . . . On our return from Texas, we stopped at 'Tucker, Oklahoma, near to the Cimarron river, and examined for a day the exposures and bad lands of the Upper Permian of that region. Although the exposures are most favorable for the exhibition of any fossils which the strata may contain, nothing of organic origin was found. Crystallized gypsum is very abundant." [E. D. Cope, Proceedings Academy Natural Science, Philadelphia, 1894, pt. I., pp. 64, 67.]

In 1896 Professor Cragin published a detailed account of the Red-Beds, which he referred to the Permian system and subdivided into ten formations. The evidence upon which this correlation is based is apparently about the same as that of Professor Hay. The statement of Professor Cragin is as follows: "The Permian of the Kansas-Oklahoma basin undoubtedly has many similarities to that of Texas, but it is probably in only one or two of the terranes of the Upper Permian, especially in the Medicine Lodge gypsum, that stratigraphic continuity or even parallelism of physico-geographic conditions can be traced between them. It therefore seems unnecessary to treat the Permian north and south of the Ouachita. mountain system as belonging to two distinct basins, and profitless to attempt divisional correlations between them (F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, vol. VI, pp. 2, 3). Professor Cragin's table of formations for the Red beds is as follows:

| The Cimarron Series | |

|---|---|

| Divisions | Formations |

| Kiger | Big Basin sandstone |

| Hackberry shales | |

| Day Creek dolomite | |

| Red Bluff sandstones | |

| Dog Creek shales | |

| Salt Fork | Cave Creek gypsum |

| Flower-pot shales | |

| Cedar Hills sandstones | |

| Salt Plain measures | |

| Harper sandstones | |

| F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, vol. VI, p. 3 | |

This division of the Red-Beds seems to have been carried to a greater extent than the differences in the lithologic characters of the rocks would justify for the rank of a formation. Perhaps it is well enough to consider them as sub-formations, and group the whole mass of rocks in three formations, as will be indicated in the closing part of this subject. The names used by Professor Cragin for these divisions are based upon names of localities occurring, with one exception in southern Kansas. The lowest terrane, termed Harper sandstones, which Professor Cragin estimates as having a thickness of 650 feet, is named from the exposures of brownish red sandstone and shale quarried near the city of Harper in Harper County. The Salt Plain measures are named from the Salt Plain along the Cimarron river in the northern part of Oklahoma. The Cedar Hills form the bluffs along the eastern side of the Medicine Lodge river in southeastern Barber County, which is the typical region for the Cedar Hills sandstone. The variegated shales called the Flower-pot shales are well exposed on a mound between East and West Cedar creeks, eight miles southwest of Medicine Lodge, locally known as the Flower Pot mound. The Cave Creek gypsums include the Medicine Lodge gypsum capping the Gypsum Hills southwest of Medicine Lodge, and the higher bed of gypsum in the southeastern part of Comanche county along Cave creek, which has suggested the name for that terrane. The Dog Creek shales are named from the exposures along the creek of that name which enters the Medicine Lodge river between Mingona and Lake City, Barber County. The Red Bluff sandstones are conspicuous along Bluff creek in western Comanche and eastern Clark counties, where they have a thickness of perhaps 200 feet. The thin dolomite in the upper part of the Red-Beds is named Day Creek from its exposures near the head-waters of that creek in the eastern part of Clark County; while the Hackberry shales are named from exposures along the creek of this name in the northern central part of Clark County. Capping the Red-Beds is the Big Basin sandstone material named from the Big basin in the western part of Clark County, which is referred by the writer to the Comanche series.

Finally, on the "Geologic map of Kansas" by Professor Haworth this terrane is termed the Red-Beds without making any further correlation than assigning it a position between the Permian and Comanche. The northern apex of the Red-Beds is represented on the map as in the southern part of Reno county, its eastern line extending southerly across Kingman and Sumner counties to the state line, then the formation extends westerly across western Sumner, Kingman, Harper, Barber, Comanche and Clark counties into the southeastern part of Meade.

Description

The greater part of the rocks belonging to the terrane popularly called the Red-Beds, for which it is proposed to adopt Professor Cragin's name of Cimarron series, consists of red sandstones and shales some of which when wet are of a bright red or almost vermilion color. The sandstones are soft and friable, while the shales are arenaceous or argillaceous. Thin layers of grayish to greenish-gray sandstone and grayish spots are not of infrequent occurrence. Near the middle of the terrane the shales contain considerable deposits of salt. This part of the series has been quite fully described by Professor Cragin who considers that the saline crust of the Salt Plain of the Cimarron river in northern Oklahoma is derived from these shales. The rock salt penetrated by the Pratt salt well is also apparently correctly referred to this portion of the Red-Beds. Above these salt shales are some red sandstones after which shales of variegated color predominate for 100 feet or more in which are thin layers of satin spar, selenite and other forms of gypsum. Capping these shales is the main mass of gypsum, which is so conspicuously shown on top of the Gypsum Hills to the southwest of Medicine Lodge and which may be readily followed along the bluffs, to the west of the Medicine Lodge river, into the southeastern corner of Kiowa county; or again, from the Gypsum Hills into the southeastern part of Comanche county. The Medicine Lodge gypsum is correlated by Professor Cragin with the similar massive deposits occurring in the central and southern parts of Oklahoma for he said "the principal stratum of gypsum described and illustrated in their Red River Report by Captain Marcy and Dr. Shumard as occurring on the Canadian and on the forks of the Red river, can scarcely be other than the Medicine Lodge gypsum" [F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, Vol. VI, p. 30]. If this correlation be correct, and the general similarity of the Oklahoma gypsum with that of the Medicine Lodge is well shown in the descriptions of Captain Marcy and George G. Shumard and the accompanying plates, then the Medicine Lodge gypsum is the most important division of the Red-Beds for the purpose of classification [Exploration of the Red River of Louisiana in 1852, published 1854, pp. 23, 165. See also plates 4, 5 and 6. (Ex. Doc. House Rep. 33d Cong., 1st Ses.)].

Succeeding the massive gypsum are bright red shales and sandstones that are more brilliantly colored than any other part of the series and are admirably exposed along the bluffs of Bluff creek in Comanche and Clark counties. An excellent illustration of these bluffs is given on p. 39 of Professor Hay's bulletin. Gypsum is not so abundant in this upper portion of the Red-Beds but near the top in Clark County is a conspicuous stratum of magnesian limestone called the Dog Creek dolomite by Professor Cragin.

In western Sumner, Harper and Kingman counties the country is gently rolling and the slopes of the low hills and banks of streams show frequent exposures, though there are many beds of sand along the valleys of the streams which have been generally, and probably correctly, referred to the Quaternary [See Bulletin U. S. Geological Survey, No. 57, pp. 38-45, Washington]. In eastern Barber County in the buttes to the north of Sharon and the Cedar Hills to the south, the rugged and picturesque country of the Red-Beds begins, which has been so strikingly described by Professors Hay and Cragin. This region, with frequent steep buttes and streams lined by steep bluffs, extends across Barber, Comanche and Clark counties to the eastern part of Meade. These bluffs and buttes afford numerous excellent sections of the upper part of this series, the thickness and general lithologic characters of which may be seen in the various sections accompanying this Report. The best exposures of the middle part of the series, as well as some of the most picturesque portions of this country, may be seen in Barber County, in the Cedar Hills in the southeastern part of the county and along the steep line of bluffs and hills to the west of the Medicine Lodge river, especially in the Gypsum hills to the southwest of the city of Medicine Lodge. When seen from the hills to the east of Medicine Lodge, at a distance of ten miles, in the early morning sunlight they form a 1andscape of striking beauty which once seen will never be forgotten. The reddish color of the steep sides of the hills whose walls suggest gigantic fortifications, is clearly visible, while the top of the hills appears in the hazy distance like a great table land. This scene has been forcibly described by Professor Cragin as follows: "If on the road from Harper to Medicine Lodge, the traveler finds himself looking westward across the valley of the Medicine Lodge river on one of those enchanting days for which southern Kansas yields the palm to no other locality, the autumn air being tinged with just enough of haze to purple the remoter vistas of the ruddy landscape

"The splendor falls on castle walls"

which rear themselves seemingly as low mountains or buttressed escarpments of a table land crowning the further incline of the valley and bounding a considerable part of the western horizon." [F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, Vol. VI, p. 28.] An earlier brief, graphic description of this region was published by Professor Hay in Harper's Magazine accompanied by a picture giving a characteristic view of several of the hills, or more accurately buttes. Professor Hay said: "A geological series of rocks, termed provisionally Jura-Trias, has been laid bare by immense erosion, and carved into the most fantastic forms of capped pinacles, mansard roofs, and frowning precipices. . . . Arenaceous limestones [sic.], of a dull red or rich brown, are alternated with beds of red clay or greenish shale glistening with crystals of selenite, and in the precipitous fronts banded with white satin spar for hundreds of yards continuously. Near the top, a massive layer of white gypsum, from eight to eighteen feet thick, makes a prominent ledge, for miles, capping the red precipice with a glaring light." [Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Vol. LXXVII, 1888, p. 43. See the picture on p. 41.]

An idea of these hills, part of which form a mesa of some extent and others simply buttes, capped by the massive Medicine Lodge gypsum, may be gained from Plate XIII. which gives a view of the Northern end of the Gypsum hills, as seen from the south. Two buttes are shown at the northern end of the hills capped by a massive stratum. To the south is the main part of the Gypsum hills the top of which is higher than the buttes. The foreground gives an idea of the broken nature of the country.

A section from Medicine Lodge to the top of the Gypsum Hills, six miles southwest, was measured by the barometer. It is thought, however, that the thickness of the different divisions is quite accurately given since the total thickness of the beds agrees very closely with the altitude of the hills above the level of the Medicine Lodge river, which is 350 feet according to the Medicine Lodge sheet of the U. S. Topographic map.

| Section from Medicine Lodge River to the top of the Gypsum Hills | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Feet | |

| 4. | Massive gypsum on top of the Gypsum Hills, 6 miles southwest of Medicine Lodge. The Medicine Lodge gypsum of Cragin. | 29-349 |

| 3. | "Iron rock" of the quarrymen, at the base of the massive gypsum. Then, mainly red shales, though other colors occur with thin layers of gypsum and selenite. | 90-320 |

| 2. | Greenish-gray sandstone, containing nodules of gypsum, forming a conspicuous stratum near the base of the steepest part of the hills. Below, mainly red shales with some thin layers of gypsum. | 80-230 |

| 1. | Mainly soft red sandstones with some shales, containing gray to greenish-gray layers and spots. Level of Medicine Lodge river.* | 150-150 |

| * Through an error the thickness of this section was not given correctly on the accompanying diagrammatic section. | ||

Nos. 2 and 3 of the above section belong in the division which Professor Cragin has named the Flower-pot shales. The soft red sandstones below these shales, forming the upper part of No. 4, belong in the Cedar Hills sandstone of Cragin, while the base of the bluffs near the river is probably in the division that he terms the Salt Plain Measures, though there is hardly any line of separation between the two divisions.

On top of the Gypsum Hills, eight miles by the road, southwest of Medicine Lodge, is Best Brothers' quarry in the massive ledge of light gray to whitish gypsum, where it has a thickness of 29 feet. At the bottom of the quarry is a reddish to greenish very hard stratum termed the "iron rock" by the quarrymen. The base of the gypsum is darker in color than the upper part and is somewhat impure. Next is the hard marble like kind called the Terra alba, and above, reaching to the surface is the softer white gypsum said to be of the best quality. On the eastern slope of the Gypsum Hills in the numerous ravines and small canyons which mark their sides are fine examples of erosion. The sloping sides are partly covered with talus and marked here and there by projecting ledges formed by harder strata. From the summit of the Gypsum Hills is a magnificent view displaying a bewildering number of isolated buttes and mounds, separated by small valleys to the west and north, and on the east and south the valley of the Medicine Lodge river limited by the red bluffs to the east. All of this region affords an excellent illustration of the effects of erosion on soft rocks that may well be compared to the Tertiary Bad Lands of Dakota.

To the west of the Gypsum Hills, eight miles southwest of Medicine Lodge is the prominent mound known as the Flower Pot mound. It forms the end of the divide between east and west Cedar creeks and is the type locality of the shales below the Medicine Lodge gypsum which Professor Cragin has called the Flower Pot shales.

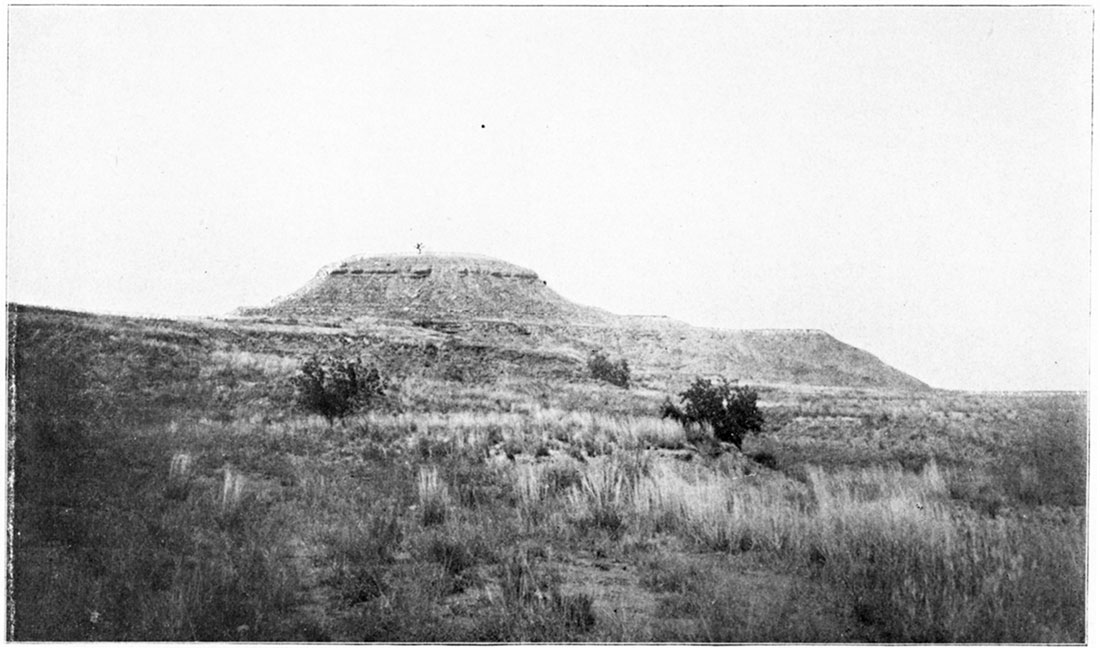

Plate XIV gives a view of Flower Pot Mound, as seen from the south. The cedar trees on top of the mound are shown and the heavy stratum forming the top of the steep part stands out quite clearly. Below are two terraces before reaching the base in the eroded valley. An idea of the sparse vegetation covering the slopes of the mound is also given. The upper part is a greenish-gray massive stratum above which on the ridge to the west is the heavy gypsum. The mound consists largely of reddish shales but these have a mottled appearance due to the presence of greenish, bluish and other colored shales, together with immense numbers of small pieces and thin layers of various kinds of gypsum, especially selenite. The steep part of the mound is about 120 feet in hight, the base of which is about lOO feet above the level of East Cedar creek. On account of the gently rolling country over which the lower part of the Red-Reds is exposed, it is a difficult matter to determine their thickness from the surface exposures. The well record at Anthony, however, affords reliable data for this portion of the terrane which gives 551 feet of the Red-Beds. All of this is referred by Professor Cragin to the Harper sandstones, while he considers Anthony as 100 feet below the top of this, division which would give a thickness of 650 feet for the Harper sandstones. The remaining divisions of the Red-Beds, Professor Cragin, from surface exposures, estimated to have a thickness of from 680 to 680 feet, which would make the thickness of the entire series vary from 1280 to 1330 feet. If Professor Cragin's interpretation of the record of the Pratt well be correct, the total thickness of the Red-Beds must be fully as great as that just given, for the Pratt well passed through 626 feet of red shales and sandstones before reaching the Salt Plain Measures which are given as 155 feet thick. Consequently the Pratt well gives a thickness of 781 feet of Red-Beds before reaching the Harper division. [F. W. Cragin, Colorado College Studies, Vol. VI, p. 23.] If this 781 feet be added to the 650 feet of Harper sandstones it will give a thickness of 1431 feet which must certainly be regarded as the maximum thickness of the Red-Beds in southern Kansas. Professor Hay first estimated the thickness of the Red-Beds, where not eroded, from Anthony westward as over 1000 feet. [Robt. Hay, Bulletin U. S. Geological Survey, 1890, No. 57, p. 26. Washington.]Plate XIV—Flower-pot Mound, "Red-Beds," eight miles northwest of Medicine Lodge (photograph by Prosser, 1896).

Later, he apparently considered this too great for in his table prepared in 1892 giving the thickness of the Kansas rocks, he gives to the Red-Beds which included the Wellington shales, a thickness of 900 feet. [Eighth Biennial Report Kansas State Board of Agriculture, Pt. II, p. 101, Topeka, 1893. Under the description of the Red-Beds is the statement that from the top of the Salt Measures to the plateau above the gypsum in Barber County they are over 800 feet thick (p. 105). This of course did not include the 200 feet or more of Red-Beds now known above the gypsum In Clark County.]

The result of the studies of the various sections west of the Medicine Lodge river indicates a thickness of at least 590 feet of Red-Beds to the west of this valley, in the regions where the upper part of the beds has suffered the least erosion. Apparently all of the deposits west of the Medicine Lodge river are above the Red-Beds penetrated in the Anthony well, which would give a thickness of 1140 feet for the entire series. It seems to the writer that the above is probably an underestimate rather than an overestimate for the total thickness of the Red-Beds.

Careful search was made in the Red-Beds for fossils, especially in all places where a change of color seemed to indicate a possibility of finding organic remains, but without success. This but repeats the experience of former investigators of this terrane in Kansas and judging from the known scarcity of fossils in similar formations in other regions there seems little probability of finding them in the Red-Beds of southern Kansas. The great assistance that fossils would afford in determining the age of the Red-Beds was fully appreciated and on this account special efforts were made toward their discovery which however proved fruitless.

Correlation