Prev Page--Introduction || Next Page--Faunal Summary

Stratigraphic Classification

Morrowan Series

Belden formation

The Belden shale was named by Brill (1942) as a member of the Battle Mountain formation in the Gore area, Colorado. The type locality was given as the north side of Rock Creek valley along U.S. Highway 24, 0.2 mile north of Gilman, Colo. Later, Brill (1944) proposed that the Belden shale be recognized as the basal formation of the Pennsylvanian in the region from Gore Creek to the White River uplift and substituted the older name Maroon formation for all Pennsylvanian rocks above the Belden shale. In this report I propose to refer to the Belden formation the Belden shale of Brill and limestones of equivalent age in the Uinta Mountains of northwestern Colorado and eastern Utah.

The Belden formation is more than 125 feet thick at the type section which is composed largely of interbedded dark-gray limestone and black fissile to dark-gray blocky shale and at least one thin coal seam. All the type section is not well exposed, as Brill pointed out, large intervals being covered by talus. The formation is about 200 feet thick near Minturn, Colo., about 4 miles north of the type section.

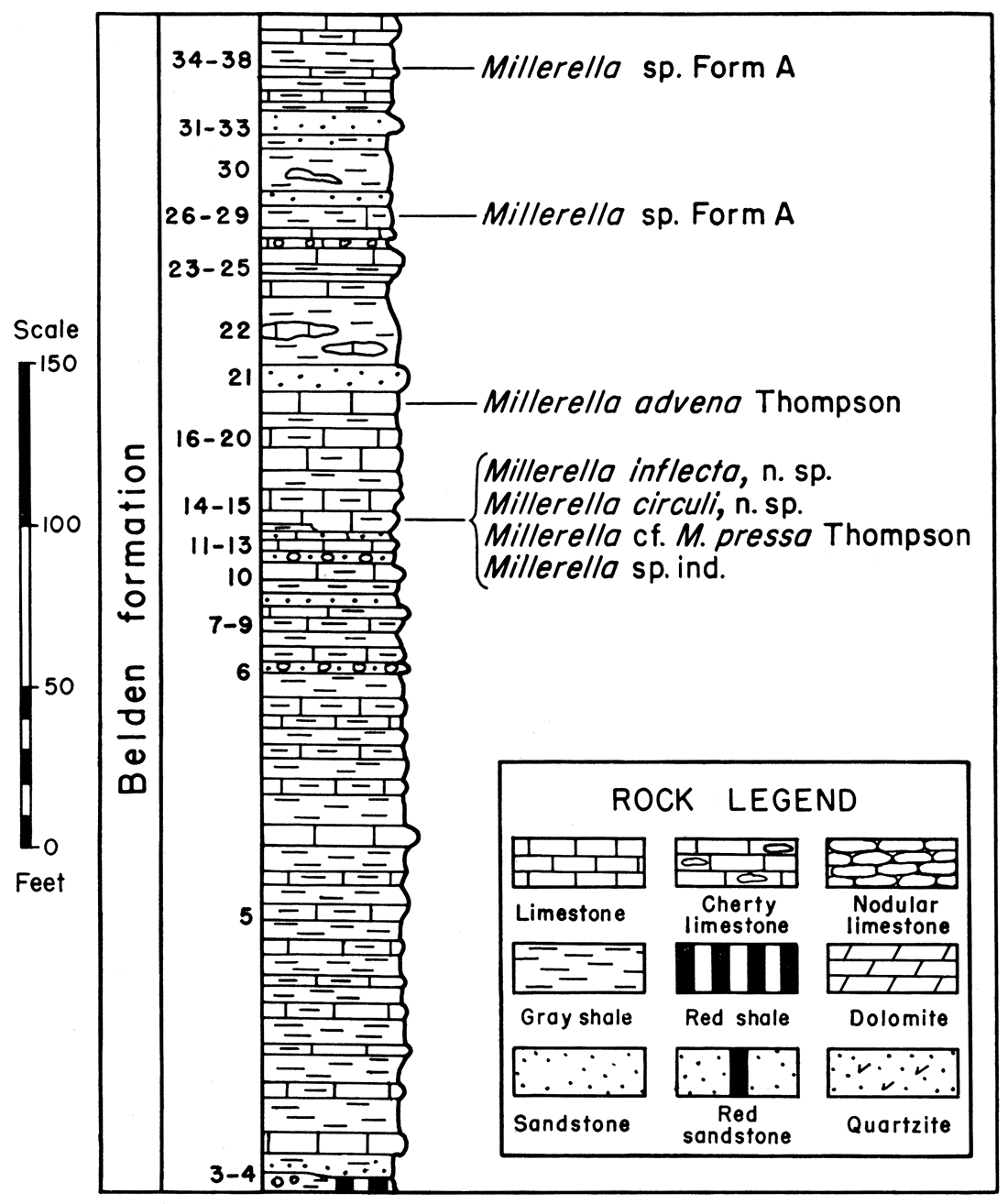

The best exposed section of Belden beds observed in the White River uplift is about one-fourth of a mile west of the junction of Sweetwater Creek and Colorado River. Here the formation is well exposed throughout and is about 346 feet thick. This section is similar in lithology to the type section and is composed largely of dark-gray earthy to light-gray crystalline limestone interbedded with dark-gray to black fissile to blocky shale. However, limestone beds are more common and thicker than at the type locality. Also, several thin conglomerates and sandstones occur in the middle and upper parts of the formation, and sandstones are abundant in the upper part. The lithology and some of the fusulinid faunas of the Belden formation at Sweetwater Creek are indicated on the accompanying diagram (Fig. 2). Detailed descriptions are given at the end of this report.

Figure 2—Diagram and fusulinid faunas of the Belden formation, Section P-15, Sweetwater Creek. Numbers to left refer to beds of described section. Rock legend same as used in all following diagrammatic sections.

The Belden formation contains abundant thick ledges of gray limestone in the central and western part of the White River uplift, and is composed predominantly of limestone. This westward increase of limestone in the Belden was also observed by Brill (1944, p. 626).

Many of the calcareous shales and limestones at Sweetwater Creek are highly fossiliferous. Microscopic examination of thin sections of the limestones and of washed residues of the shales reveals an abundant fusulinid fauna composed entirely of species of Millerella. This fauna is similar to that of the Kearny formation of southwestern Kansas and the type section of the Morrowan of Arkansas (Thompson, 1944). Furthermore, an examination of numerous fusulinid-bearing shales and limestones from the Sweetwater Creek section has not demonstrated the presence of the more highly developed fusulinids that are so commonly associated with Millerella in the post-Morrowan Derryan series of New Mexico and Lampasan series of Texas. It is, therefore, believed that the Belden formation is of Morrowan age. [Note: The undescribed Morrowan fossils reported by Moore, et al., (1944) from the Colorado River valley west of Minturn probably are from the Belden formation.] However, Morrowan fusulinids have not been studied in sufficient detail to determine if the Belden is early or late Morrowan in age or if it represents all the Morrowan of other areas.

Williams (1943) identified as Brazer formation 500 feet of limestones, sandstones, and shales in the canyon of North Fork of Duchesne River on the south flank of the Uinta Mountains. He also identified as Brazer formation 700 feet of rocks of similar lithology in Brush Creek Canyon on the south margin of the Uinta Mountains. He concluded that all the Brazer may be of Mississippian Meramecian to Chesterian age.

Brill (1944) described the section above the "Mississippian limestone" near Disappointment Creek southeast of Hell's Canyon. He referred 941 feet of rocks exposed in this area to the Morgan formation and stated that the Morgan rests on Mississippian limestone. The Weber quartzite above the Morgan formation, as the Morgan was thus defined, is about 880 feet thick. Brill considered all of the Morgan formation at Disappointment Creek Desmoinesian in age. A restudy of the section in the general region of Disappointment Creek indicates that Brill included at least 225 feet of limestone in the basal part of the Morgan formation that corresponds in age to the upper part of the Brazer formation as defined by Williams in Brush Creek and Duchesne River Canyons.

Detailed measurements and numerous collections were made of the limestones and interbedded thin gray to red shales that occur just beneath the rocks referred to the Morgan formation by Williams in the Uinta Mountains. At many localities the lower part of these limestones and thin shales is covered by talus, and the basal beds were studied in detail at only a few places. At Juniper Mountain they seemingly are unconformable on older rocks. The contact with overlying rocks was observed at numerous localities, and in many of them it is unconformable. Heavy basal conglomerates in the overlying beds occur on an irregular surface at the top of the limestones and include chert and limestone pebbles believed to have been derived from the rocks below.

Most of this limestone and thin shale sequence is highly fossiliferous. Fusulinid foraminifers referable to Millerella are exceedingly abundant at many localities, including Sheep Mountain Canyon, White Rock Canyon, Duchesne River Canyon, Split Mountain Canyon, Hell's Canyon, and Juniper Mountain Canyon. Many of the species of Millerella found in this part of the section in the Uinta Mountains are also present in the Belden formation of the Sweetwater Creek section. Furthermore, as at Sweetwater Creek, in spite of the great abundance of forms of Millerella, numerous thin sections of limestones and washed shale samples have not yielded any of the more advanced forms of fusulinids that occur in the Derryan of New Mexico. Therefore, these limestones and thin interbedded shales in the Uinta Mountains are referred to the Pennsylvanian Morrowan series.

The fusulinids indicate that the type section of the Belden formation is identical in age to at least part of these Morrowan limestones in the Uinta Mountains. This conclusion is further substantiated by the fact that in the White River uplift westward from Sweetwater Creek, the Belden formation is gradually replaced by more and more limestone. East of Meeker, the Belden formation is highly calcareous and resembles closely the Morrowan limestones of the Juniper Mountain section, about 40 miles north by northwest. Therefore, I propose to extend the Belden formation from central Colorado to the Uinta Mountains. The lithologic change from shales and interbedded limestones in the Gore area to predominantly limestones and thin interbedded shales in the Uinta Mountains is a gradual one.

Work by Girty (Mansfield, 1927, pp. 63-71; Richardson, 1941, pp. 23,24) and others (Blackwelder, 1910, p. 530; Williams, 1943) indicates that part of the Brazer limestone of Utah and Idaho is of Spergen to Chester (Mississippian) age. Accordingly, it seems that at least a part of the typical Brazer formation west and northwest of the Uinta Mountains in Utah probably includes rocks older than the Belden formation of the Uinta Mountains. Morrowan rocks, however, probably were also included in the typical Brazer of Richardson (1913). Until a more definite correlation can be made with the Wasatch Mountain section, I prefer to use the term Belden formation for the Morrowan rocks of the Uinta Mountains. [Note: After this paper was in press, J. Stewart Williams and James S. Yolton (Am. Assoc. Petroleum Geologists Bull., vol. 29, pp. 1143-1155, 1945) identified Morrowan rocks in the lower part of the "Wells formation" at Dry Lake, Logan Quadrangle, northern Utah.]

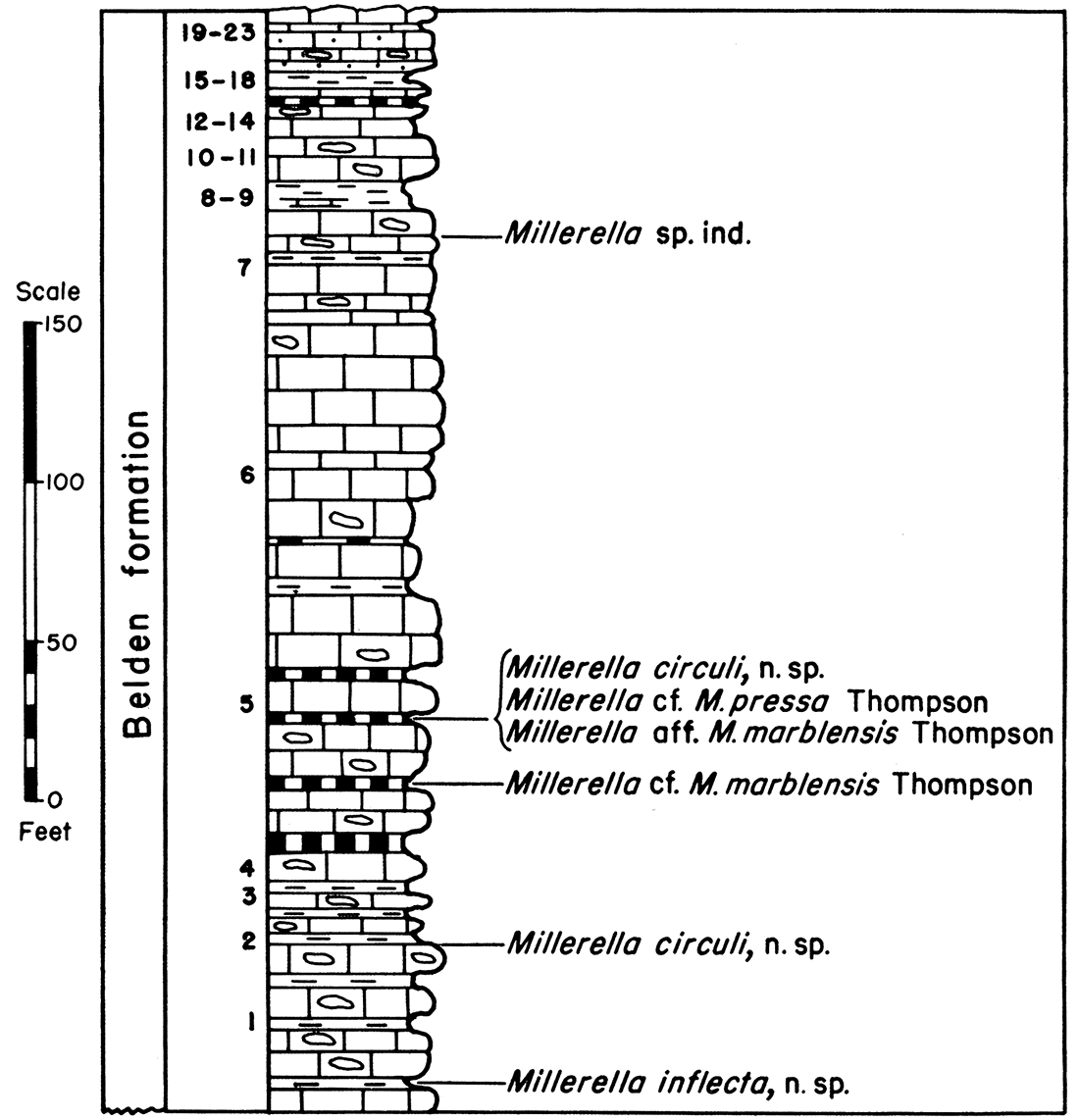

The Belden formation is more than 335 feet thick at Sheep Mountain Canyon, south of Manila on the north side of the Uinta Mountains. There it is composed predominantly of fossiliferous limestones and a few thin interbedded shales. The lithology and some of the fusulinid faunas are indicated in the accompanying diagram (Fig. 3). Descriptions of the individual beds are given at the end of the report.

Figure 3—Diagram and fusulinid faunas of the Belden formation, Section P-9, Sheep Mountain Canyon.

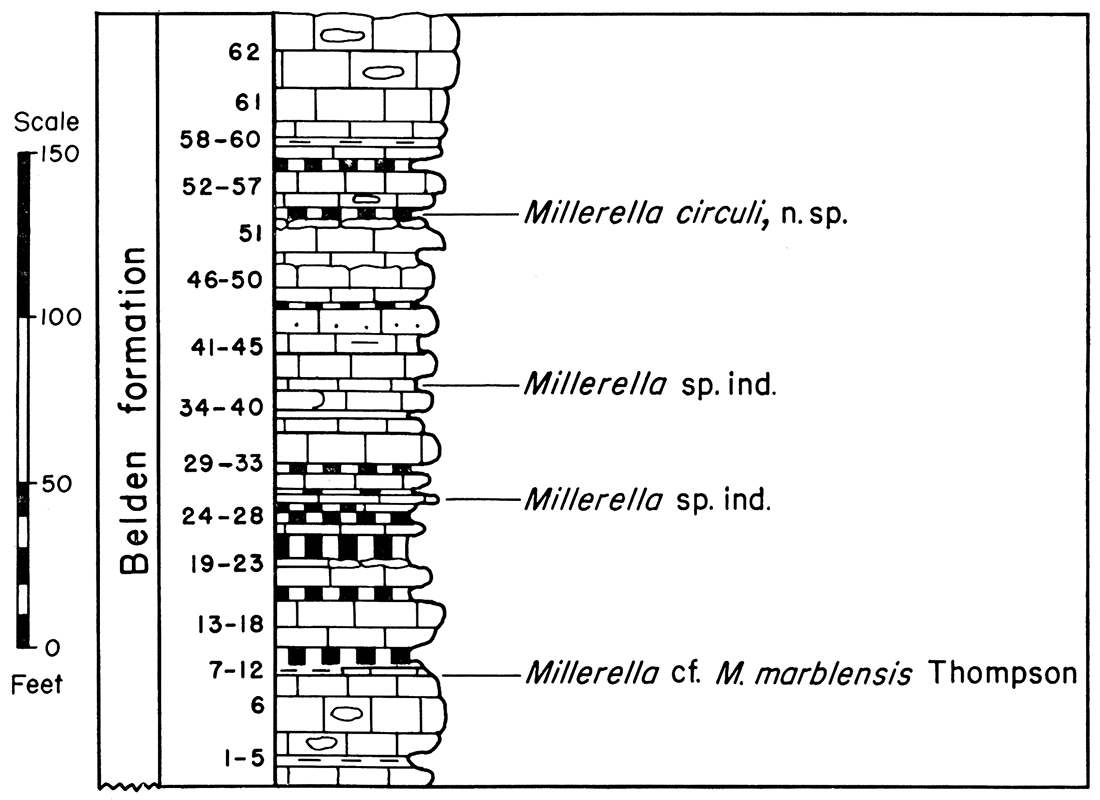

The upper 235 feet of limestone of the Belden formation was measured at Split Mountain Canyon on Yampa River. Its lithology and some of the fusulinids are indicated in the accompanying diagram (Fig. 4). At least 50 feet of limestones of the Belden formation occur at Split Mountain below the base of this measured section.

Figure 4—Diagram and fusulinid faunas of the Belden formation, Section P-10, Split Mountain Canyon.

Only the upper 126 feet of the Belden formation was measured in detail in Hell's Canyon but about 175 feet of poorly exposed limestones and interbedded shales below the measured section probably should be referred to the Belden. The upper surface of the Belden formation here is slightly irregular and the basal unit of the overlying Hell's Canyon formation is a coarse conglomerate composed of chert and limestone pebbles and yellow to red sandstone. The relations indicate an unconformity. The chert and limestone pebbles are believed to have been derived from the Belden formation.

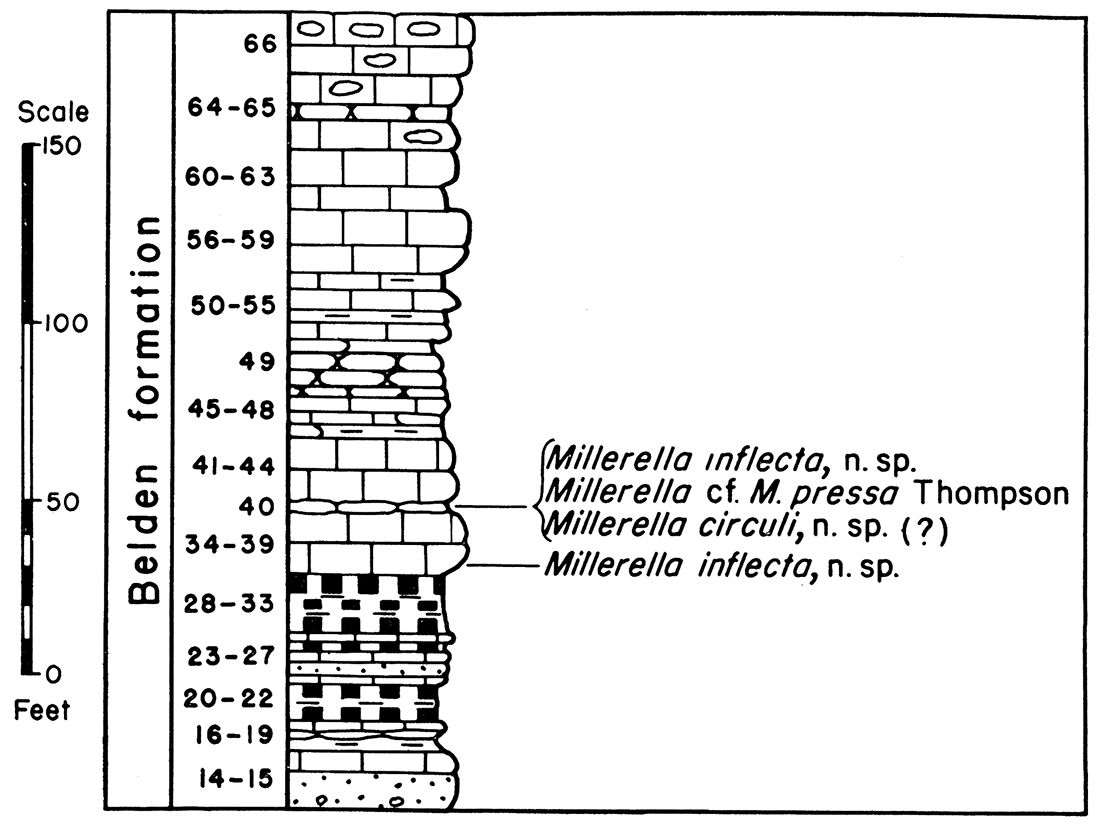

At Juniper Mountain Canyon the Belden formation is slightly more than 225 feet thick. It is composed largely of fossiliferous limestones and thin beds of red and gray shale. The general lithology and part of the fusulinid faunas are indicated in the accompanying diagram (Fig. 5). Detailed descriptions of the individual units are given at the end of the report.

Figure 5—Diagram and fusulinid faunas of the Belden formation, Section P-13. Juniper Mountain Canyon.

Post-Morrowan Pennsylvanian

General

Rocks of Desmoinesian age are widespread in northcentral Colorado, Wyoming, and eastern Utah. Roth and Skinner (1931) have described a large fauna of foraminifers, including fusulinids, from the McCoy formation at McCoy, Colo., which demonstrates that at least part of the McCoy formation is of Desmoinesian age. These workers also described a fusulinid species, Fusulina? hartvillensis Roth and Skinner, from the Hartville area of eastern Wyoming, possibly of Desmoinesian age. Thompson (1936) described 7 species of Desmoinesian fusulinids from the Hartville area. Branson (1939) reported Desmoinesian fusulinids in the "Tensleep sandstone" at Big Horn Canyon south of Thermopolis, Wyo. I have collections of Desmoinesian fusulinids from limestones immediately below the massive to cross-bedded sandstones of the type section of the Tensleep sandstone in Tensleep Canyon. Thompson and Scott (1941) described Desmoinesian fusulinids from the upper part of the type section of the Quadrant formation in northwestern Wyoming. Several thousand feet of rocks of Desmoinesian age are known to be present in the middle part of the Oquirrh formation in the Wasatch Mountains of eastern Utah.

Rocks of Pennsylvanian Derryan age are widespread in southcentral United States. However, few occurrences of Derryan rocks have been recorded from central or northern United States. Derryan fusulinids have been described from the Hartville area of southeastern Wyoming and the Black Hills of South Dakota (Thompson, 1936). Middle Derryan rocks, stratigraphically near the junction of the Zone of Profusulinella and the Zone of Fusulinella, are represented in the Hartville region of eastern Wyoming by part of the Reclamation group. The lower part of the Minnelusa formation in the Black Hills of South Dakota contains highly developed species of the genus Fusulinella, F. furnishi Thompson and F. dakotensis Thompson, which indicate that the lower part of the Minnelusa formation is late Derryan in age.

Species of Fusulinella are widespread geographically in central Wyoming, northern Colorado, and eastern Utah. Species of this genus have been discovered in the lower part of the Pennsylvanian exposed at McCoy, Colo.; along the southeast side of the Uinta Mountains of Colorado and Utah; in the Absaroka Range of northwestern Wyoming (Love, 1939); and in the Wasatch Mountains of Utah. Four species of Fusulinella are described below from rocks here referred to the Hell's Canyon formation in the eastern part of the Uinta Mountains. Detailed studies of them indicate they are more highly developed biologically than the species of Fusulinella in the Derryan of New Mexico, the Atoka formation of Oklahoma, the Big Saline group of Texas, and the lower part of the Reclamation group of eastern Wyoming. In the immediate area considered in this report, species of Fusulinella occur only a short distance above the top of the Morrowan Belden formation. The lowermost of these forms, F. iowensis var. leyi, n. var., is closely similar biologically to the typical variety of this species from near the base of the type Desmoinesian section of Iowa and the varieties of the species from the Mercer limestone of Ohio. Closely similar forms occur in the Warmington limestone member of the Elephant Butte formation of south-central New Mexico and in the Sandia formation of central New Mexico.

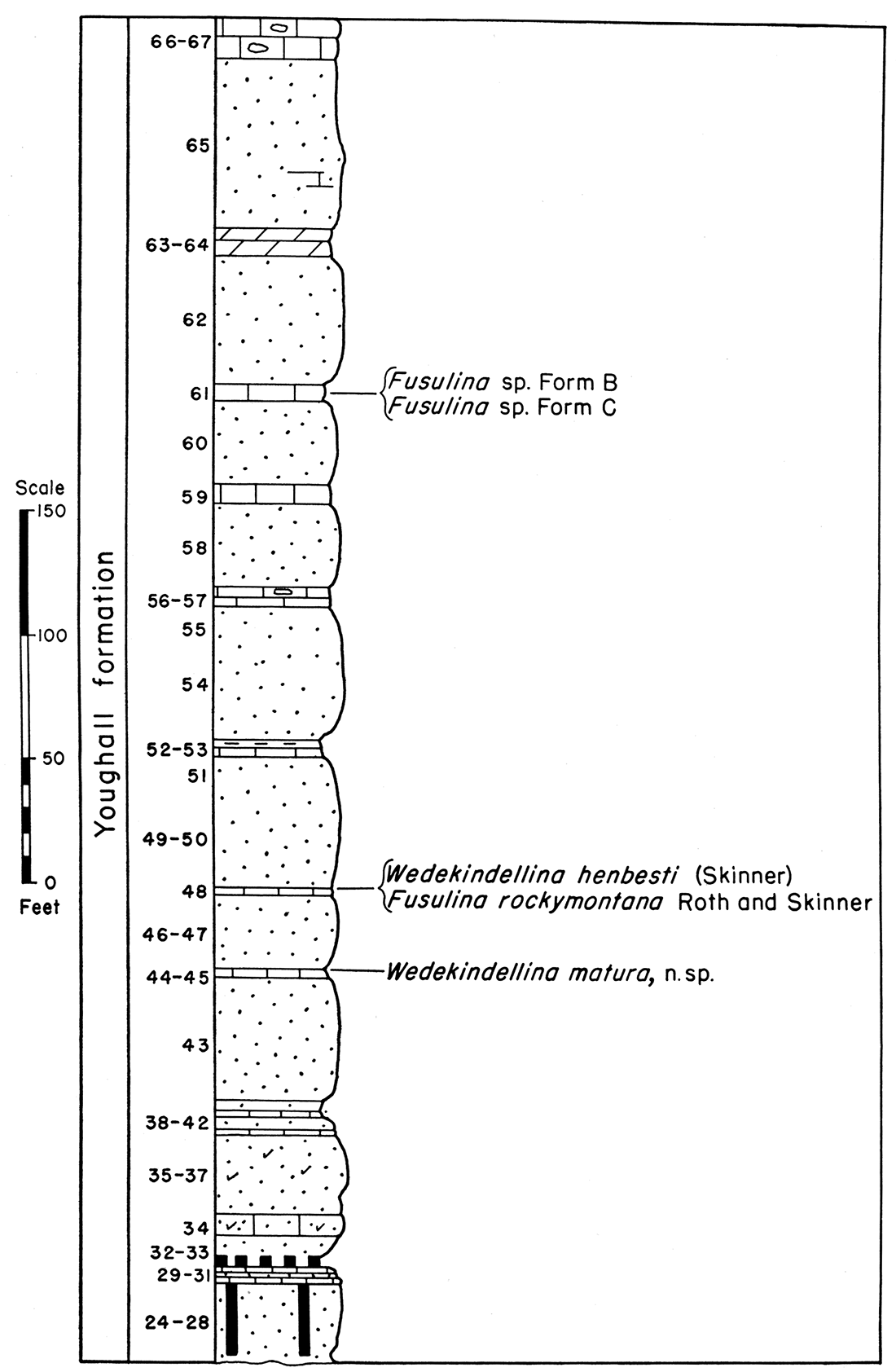

Two species of Wedekindellina and 8 species of Fusulina are described from the Youghall formation in the eastern part of the Uinta Mountains. Fusulina prima, n. sp., from the basal part of the Youghall formation, is more or less transitional in nature between typical species of Fusulinella and typical species of Fusulina. The middle and upper parts of the Youghall formation contain species of Fusulina and Wedekindellina closely similar to species in the Cherokee formation of Iowa, Missouri, Kansas and Oklahoma.

No fossil was found in the Weber sandstone of the Uinta Mountains, and its age is not known. However, the Weber may all be of Desmoinesian age.

Numerous lithologic units between the Belden formation below and the Weber sandstone above are traceable along the flanks of the eastern part of the Uinta Mountains but it does not now seem advisable to propose formational or member names for all of them. Two major lithologic and faunal units can be mapped throughout much of this area. The lower is here named the Hell's Canyon formation and the upper is named the Youghall formation. The Hell's Canyon formation is about 300 feet thick along the southeast flank of the Uinta Mountains and is composed of highly fossiliferous limestones, fossiliferous gray shales, red to purple shales, gray fissile shales, purplish siltstones, and thin beds of gray to red fine-grained sandstone. Fusulinids referable to Millerella, Eoschubertella, Pseudostaffella, and Fusulinella are abundant throughout much of the formation.

The term Youghall formation is proposed for the fossiliferous limestones, thin shales, and thick interbedded highly cross-bedded sandstones between the Hell's Canyon formation below and the Weber sandstone above. Fusulinid foraminifers assigned to Millerella, Pseudostaffella, Fusulina, and Wedekindellina occur in the Youghall formation, and the latter two genera occur throughout most of the formation along the south-central, southeastern, eastern, and northeastern margins of the Uinta Mountains. The Youghall formation is 530 to 650 feet thick. It retains an essentially uniform thickness and lithology over larger areas than the underlying Hell's Canyon formation.

The nomenclature of Pennsylvanian rocks of post-Morrowan age in eastern Utah, northern Colorado, and central to southern Wyoming is not stabilized. In central and south-central Wyoming the term Tensleep sandstone is applied to the thick sandstone at the top of the Pennsylvanian. The term Amsden has been applied to the sandstones, limestones, and shales between the Tensleep and the Mississippian Madison limestone. The Amsden has been reported as including rocks of Pennsylvanian and Mississippian ages. It is possible that rocks equivalent in age to the Belden formation may also have been included in the Amsden at its type locality. Love (1939) discovered a species of Fusulinella in the upper part of rocks which he referred to the Amsden formation in the Absaroka Range, Wyoming. Therefore, it may be that rocks equivalent in age to and older than the Belden formation, Hell's Canyon formation, and Youghall formation have been referred to the Amsden. In any case, the uncertainty in correlation between the Uinta Mountain region and the type section of the Amsden formation, more than 200 miles to the northeast, makes it inadvisable to apply the term Amsden to any rocks in the Uinta Mountains region.

The term Morgan formation was published by Blackwelder (1910) for 500 to 2,000 feet of red sandstone and shale exposed in Weber Canyon, Utah, between the "dark Mississippian limestones" below and the Weber quartzite above. If the upper limestones of the Brazer formation of Weber Canyon are equivalent in age to the Belden formation of the Uinta Mountains, part of the Morgan formation of Weber Canyon may be equivalent in age to limestones and shales in the eastern part of the Uinta Mountains included in the Hell's Canyon formation. Only a few fossils have been reported from the type section of the Morgan formation. Therefore, its age is not definitely known. Also, the lithology of the type section of the Morgan formation is considerably different from that of the Hell's Canyon formation.

Williams (1943) applied the term Morgan formation to reddish shales and reddish sandstones 215 to 385 feet thick that occur along the southwestern and south-central margins of the Uinta Mountains, stratigraphically between the Belden formation below and the "Weber formation" above. [Note: The Weber formation as defined by Williams in the Uinta Mountains includes part of the Youghall formation and all the Weber sandstone of this report.] At Brush Creek Canyon, he recognized a species of Fusulinella in the upper part of the Morgan formation. It seems probable that rocks at Duchesne River and Brush Creek, referred to the Morgan formation by Williams, are equivalent in age, at least in part, to beds on the southeastern flanks of the Uinta Mountains here referred to the Hell's Canyon formation.

Several formational terms have been proposed for Pennsylvanian rocks in north-central Colorado that are equivalent in age to at least part of the rocks between the Belden formation and the Weber sandstone. These terms include Maroon formation (as defined by Brill, 1944), McCoy formation (Roth and Skinner, 1931), and Battle Mountain formation (Brill, 1942). However, the rocks of the type sections of all these formations are markedly different in lithology from the fusulinid-bearing post-Morrowan rocks of the Uinta Mountains. It is not advisable to apply any of these terms to rocks in the Uinta Mountains.

Hell's Canyon formation

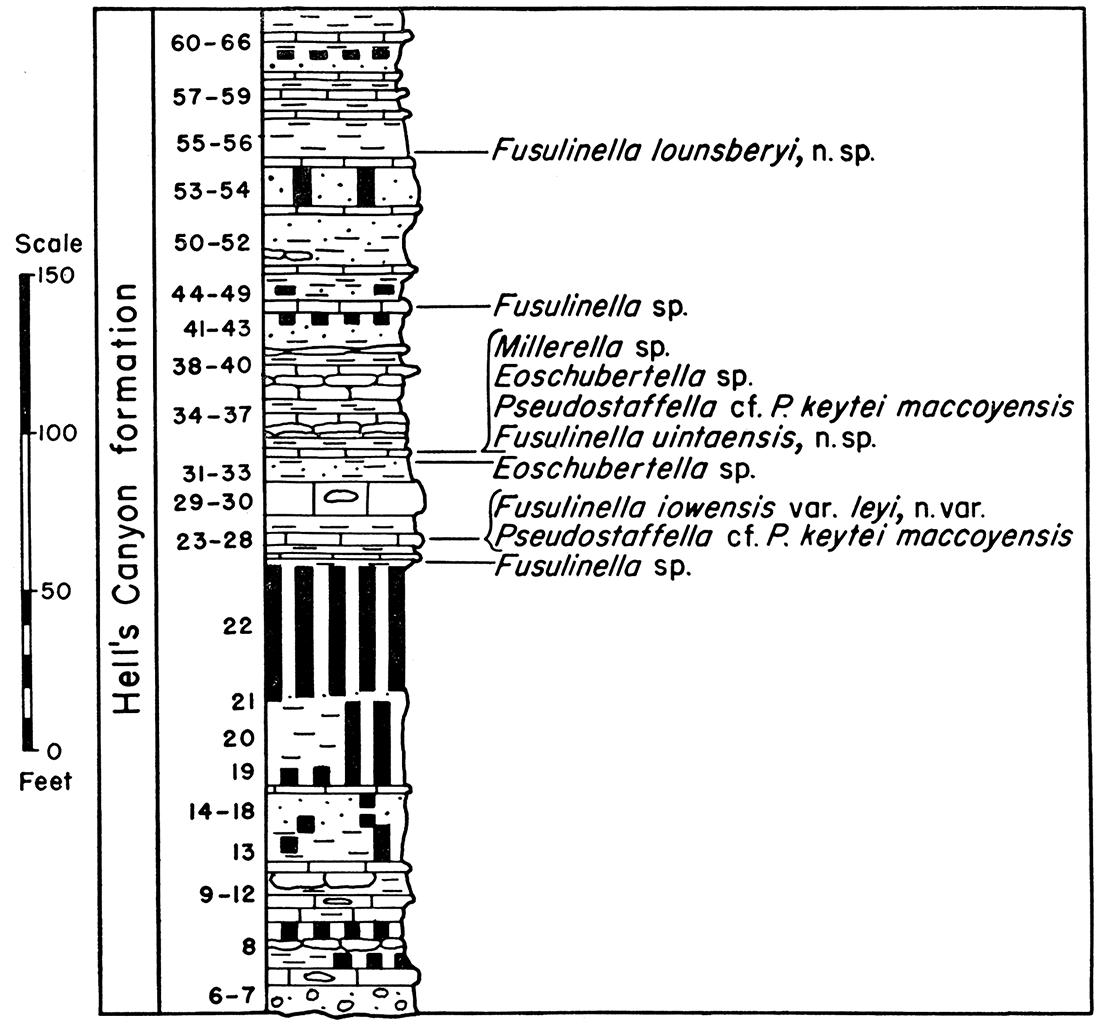

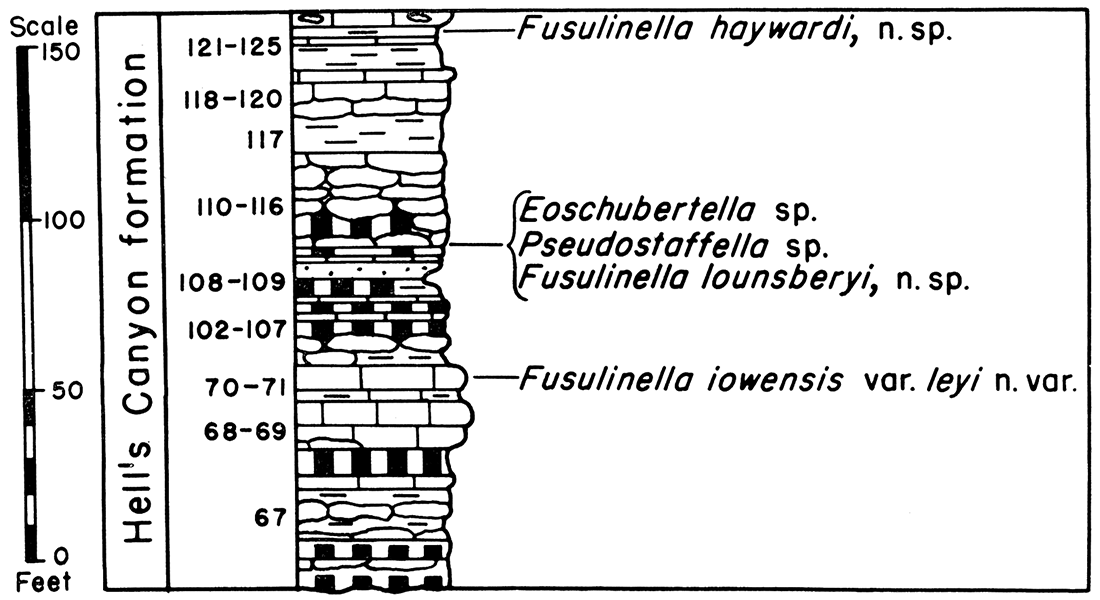

The Hell's Canyon formation is about 294 feel thick at the type locality in Hell's Canyon, west bluff Hell's Canyon, sec. 31, T. 6 N., R. 102 W, a tributary canyon of the Yampa River in Moffat County, Colo. The type section is composed of highly fossiliferous limestones and gray shales, red to purplish shales, gray fissile shales, purplish siltstones, and thin beds of gray to red fine-grained sandstones. The lower 10 feet of the type section is a coarse conglomerate of limestone and chert pebbles and yellowish to red coarse quartz sand. The next 125 feet consists largely of purplish shale, interbedded with irregular argillaceous limestone zones, purplish siltstone, and argillaceous limestone. Fossils are abundant in several zones of this interval, especially about 50 feet below the top, but no fusulinid has been discovered in this part of the section. The upper 159 feet of the type section is composed largely of highly fossiliferous cherty limestone, fossiliferous shale, scattered thin beds of red to purple shale, and gray to purple fine-grained sandstone. Fusulinids referable to Fusulinella, Pseudostaffella, Eoschubertella, and Millerella are abundant from the base to within 29 feet of the top of this upper interval. The lithology and some of the fusulinid faunas of the type section are indicated in the accompanying diagram (Fig. 6). Detailed descriptions are given at the end of this report.

Figure 6—Diagram and fusulinid faunas of the Hell's Canyon formation, Section P-17, Hell's Canyon.

The Hell's Canyon formation is exposed throughout most of the northeast wall of the canyon of Yampa River at Juniper Mountain. Thrust faults that more or less parallel the northeast-dipping strata repeat large parts of the section at some places. The most nearly complete exposure of the Hell's Canyon formation at Juniper Mountain was found near the east end of the canyon. The total thickness of the formation at Juniper Mountain is more than 165 feet. However, rock flowage caused by thrusting probably has eliminated large parts of the shale beds and possibly limestone beds. At Juniper Mountain the formation is composed largely of highly fossiliferous limestones and interbedded fossiliferous gray shales, red to purple shales, and thin sandstone. Fusulinid foraminifers are abundant throughout the Hell's Canyon formation at Juniper Mountain; in fact, several beds are composed largely of shells or Fusulinella, Pseudostaffella, and Millerella. Many species found at this locality are also present at the type section.

The lithology and fusulinid fauna of the Hell's Canyon formation at Juniper Mountain are indicated in the accompanying diagram (Fig. 7). Detailed descriptions of individual beds are given at the end of the report. A comparison of this diagram and detailed descriptions with those representing the type section indicates that the formation is more highly marine at Juniper Mountain than at Hell's Canyon. Also, red shales and siltstones are less abundant at Juniper Mountain than at Hell's Canyon. The section exposed at Cross Mountain, west by north of Juniper Mountain, indicates that this lateral lithologic change is a gradual one.Figure 7—Diagram and fusulinid faunas of the Hell's Canyon formation, Section P-13, Juniper Mountain Canyon.

At Split Mountain and in the area farther west along the south flank of the Uinta Mountains, rocks believed to be equivalent in age to the type section of the Hell's Canyon formation are largely reddish to brown fine-grained sandstone and siltstone and red shales, with a few interbedded thin argillaceous and sandy fossiliferous limestones. The total thickness of rocks equivalent in age to the Hell's Canyon formation was not determined at Split Mountain or in the region farther west. It seems probable that rocks of the same age as the Hell's Canyon formation are replaced by red sandstones and shales of the Morgan formation (Williams, 1943) west of Split Mountain.

Youghall formation

Several hundred feet of cross-bedded sandstone and interbedded fossiliferous limestones and shales occur around the margins of the Uinta Mountains below the Weber sandstone and stratigraphically above the Hell's Canyon formation. The faunas, especially the fusulinids, demonstrate that these rocks are all of Desmoinesian age. The type section of the Weber quartzite (King, 1876; Hague and Emmons, 1877; Williams, 1943) includes several fossiliferous limestones in the lower one-third. It is possible that the lower part of the type Weber is equivalent in age to part of these Desmoinesian rocks. However, in the Uinta Mountains area I restrict the term Weber to the thick cross-bedded to massive buff sandstones above the limestone-bearing part of the section. As the Weber is thus defined for this region, the limestones, sandstones, and thin shales stratigraphically between the Hell's Canyon formation and the Weber sandstone are without a formational name. I propose the name Youghall formation for them.

The term is derived from the old stage station of Youghall, east of Hell's Canyon. However, the type locality is here designated as the exposures on the west side of Hell's Canyon in sec. 31, T. 6 N., R. 102 W. and along the east side of the head of Hell's Canyon in the W2 sec. 7, T. 5 N., R. 102 W., Moffat County, Colo. The base of the type section and its contact with the underlying Hell's Canyon formation can best be seen on the west wall of Hell's Canyon in the east face of the cliff near the center of the east-facing rounded hill of section 31, mentioned above. The upper part of the formation is best exposed about one-fourth mile northwest and down Hell's Canyon from its head at the creek fork in the south part of section 7.

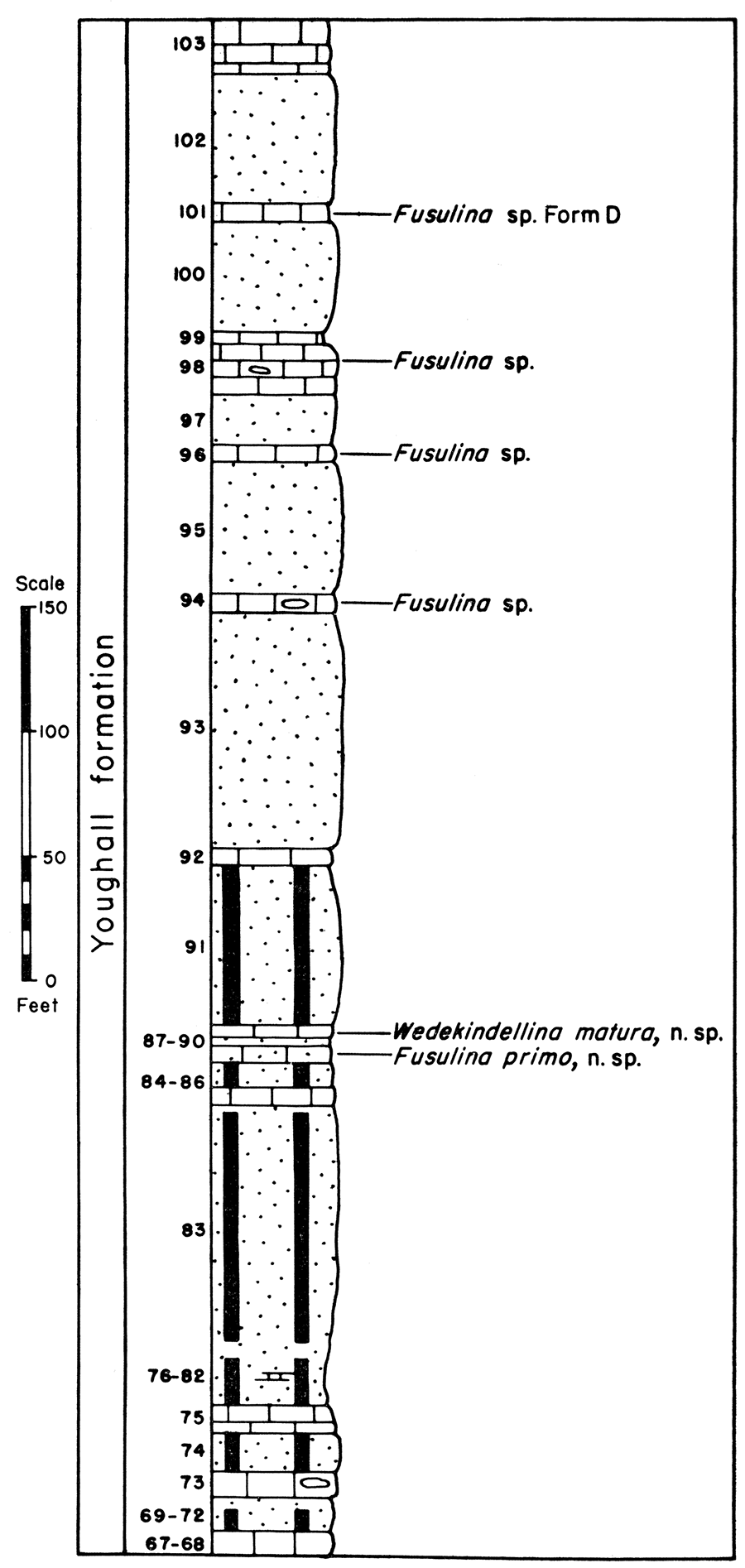

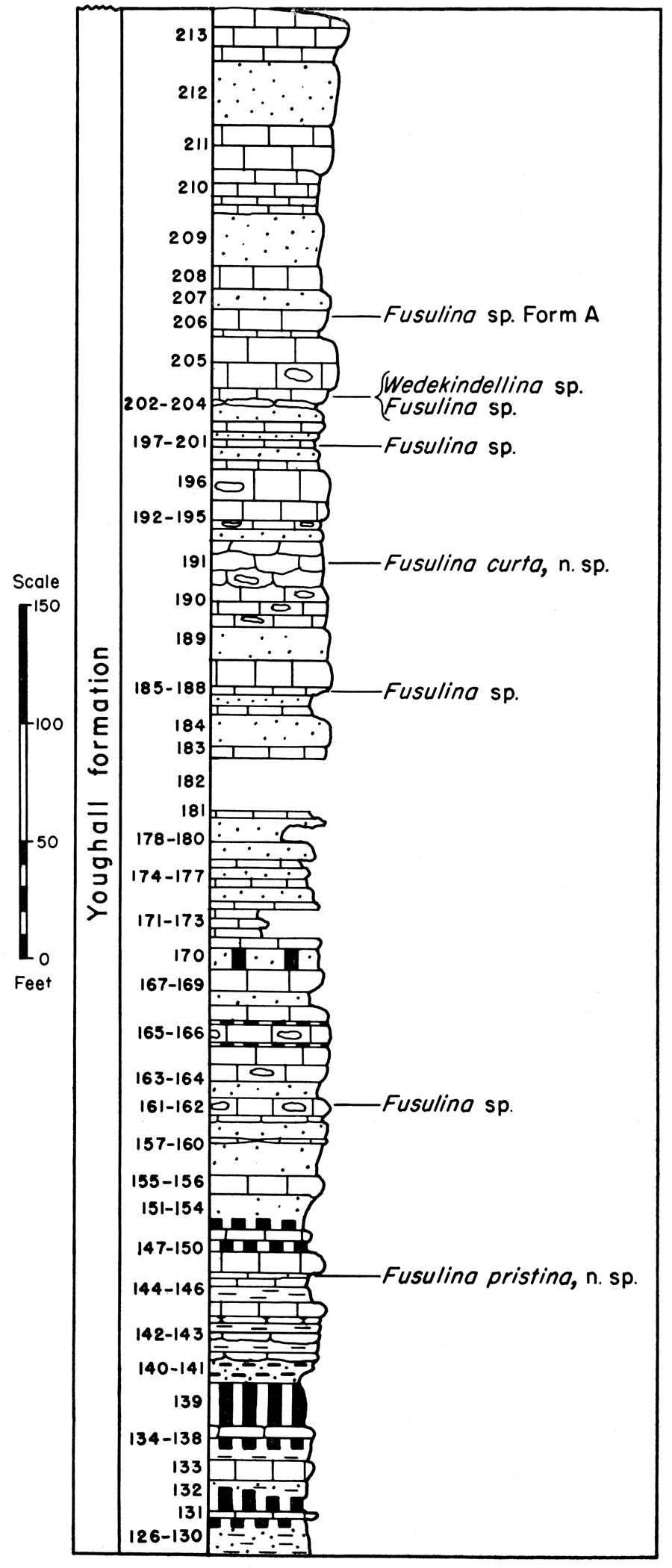

The type section of the Youghall formation is approximately 625 feet thick and is composed of cross-bedded to massive buff to reddish-brown sandstone and interbedded highly fossiliferous limestone. The lithology and fusulinid faunas of the type section are indicated in the accompanying diagram (Fig. 8), and detailed descriptions of individual units are given at the end of the report. The accompanying diagrams indicate the lithology and some of the fusulinid faunas of the formation at Juniper Mountain (Fig. 9) and at Sheep Mountain Canyon (Fig. 10). This formation is also well exposed at many other localities on the eastern and southern margins of the Uinta Mountains, including Cross Mountain, Split Mountain Canyon, and White Rock Canyon.

Figure 8—Diagram and fusulinid faunas of the Youghall formation, Section P-17, Hell's Canyon.

Figure 9—Diagram and fusulinid faunas of the Youghall formation, Section P-13, Juniper Mountain Canyon.

Figure 10—Diagram and fusulinid faunas of the Youghall formation, Section P-9, Sheep Mountain Canyon.

At Juniper Mountain the Youghall formation is at least 650 feet thick, but its contact with the overlying Weber sandstone was not observed. Northward and northwestward the formation decreases in thickness. At Split Mountain it is more than 500 feet thick, at White Rock Canyon at least 600 feet thick, and at Sheep Mountain Canyon about 530 feet thick. On the south and southeast margins of the Uinta Mountains the Youghall formation overlies the Hell's Canyon formation; on the southwest margin it lies on the Morgan formation (as defined by Williams); and on the north margin it rests on the Belden formation.

At Juniper Mountain more than 50 percent of the Youghall formation comprises fossiliferous and cherty limestones but at Cross Mountain slightly less than 50 percent is limestone. At Hell's Canyon the formation is made up of only about 20 percent limestone, and at White Rock Canyon it contains only about 10 percent limestone and dolomitic limestone. Thus, the limestone content of the formation decreases westward from Juniper Mountain. Also, the limestones become more highly dolomitic in the area from White Rock Canyon to Duchesne River Canyon west of Vernal, Utah. At Sheep Mountain Canyon, on the north side of the Uinta Mountains, limestones make up only about 10 percent of the formation. Thus, the limestone content decreases northwestward from Cross and Juniper Mountains.

Fusulinids are abundant in many of the limestones throughout most of the Youghall formation but they have not been found in the uppermost limestone of the formation at any locality around the margins of the Uinta Mountains. Fusulinids occur in the next to highest limestone at most localities, including the type section. At several places Fusulina and Wedekindellina have been found in the lower part of the formation and species of these genera also occur in the upper fusulinid-bearing limestones. It is believed, therefore, that all the Youghall formation is equivalent in age to the Cherokee of the midcontinent region.

The strata of the Youghall formation are essentially parallel to those of the underlying Hell's Canyon formation, the Morgan formation, or the Belden formation, and to those of the overlying Weber sandstone. No physical evidence of an unconformity at the top or base of the formation was observed in the Uinta Mountains region, but absence of the Hell's Canyon formation on the north margin of the Uinta Mountains indicates that an unconformity separates the Belden formation and the Youghall formation in that area.

Weber sandstone

The term Weber sandstone is applied to the buff, brownish, and light-gray highly cross-bedded to massive fine-grained sandstones in the Uinta Mountains between the Youghall formation below and the Park City formation above. Lenticular dolomites and dolomitic sandstones occur throughout the Weber. So far as could be determined, the contact between the Youghall formation and the Weber sandstone is conformable. The strata of the Weber sandstone and those of the overlying Park City formation are essentially parallel, at least in areas around the Uinta Mountains.

In the region north, northwest, and northeast of Vernal, Utah, the Weber sandstone is about 1,000 feet thick. Eastward from Split Mountain Canyon, the Weber decreases in thickness. On the north side of the Uinta Mountains, at Sheep Mountain Canyon, the Weber is about 850 feet thick.

No fossils were obtained from the rocks here referred to the Weber sandstone. Therefore, the age of the Weber was not determined.

Prev Page--Introduction || Next Page--Faunal Summary

Kansas Geological Survey, Geology

Placed on web Sept. 10, 2017; originally published Oct. 15, 1945.

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

The URL for this page is http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/Bulletins/60_2/03_strat.html