Prev Page--Introduction || Next Page--Geology

Geography

Topography and drainage

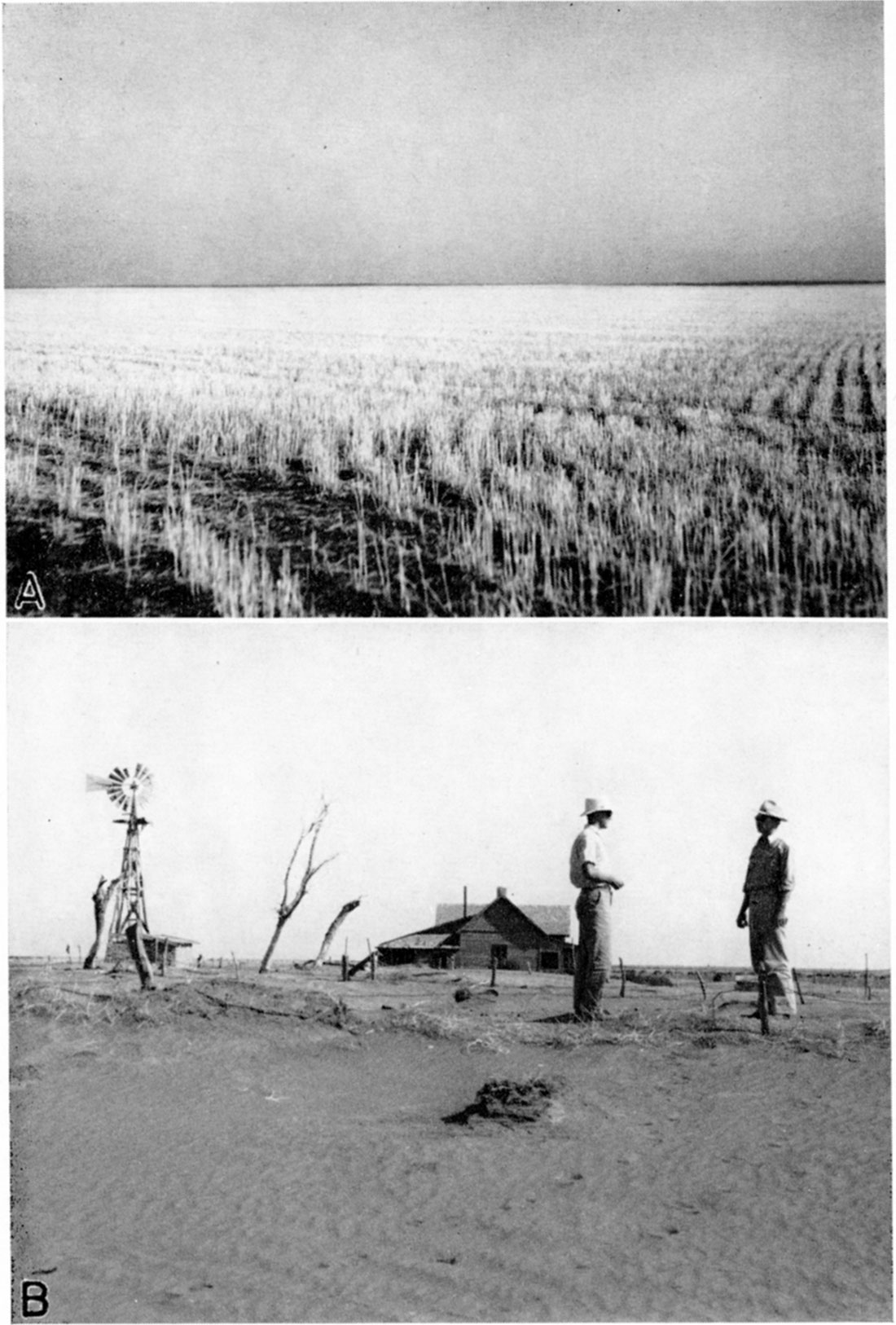

Stanton county lies in the High Plains section of the Great Plains province. In general most of the county consists of gently rolling, nearly flat, upland plains (plate 3A) that slope toward the east at an average gradient of about 20 feet to the mile. The highest point in the county, north of Bear creek along the Colorado line, has an altitude of almost 3,700 feet. North Fork of Cimarron river leaves the southeastern corner of the county at an altitude slightly less than 3,100 feet, the lowest point in the county. The maximum relief, therefore, is about 600 feet.

The monotony of the nearly flat upland surface is broken by the effects of stream erosion in many places, by a prominent ridge in the northeastern part of the county, and by an area of dune sand south of Bear creek.

A prominent ridge, trending roughly northwest-southeast, extends from a point in northwestern Grant county across the northeastern part of Stanton county, through Hamilton county, and gradually merges with the High Plains surface in eastern Colorado. In southern Hamilton county the top of the ridge is broad and smooth, but the sides are cut deeply by streams. The ridge area in Stanton county is deeply dissected by tributaries of Bear creek.

There are no permanent streams in the county-only small ephemeral streams that flow only after heavy rains have fallen in the county or in southeastern Colorado. Bear creek, the most prominent of these small streams, originates 50 miles or more west of the state line in southeastern Colorado and enters Stanton county about 7 miles north of the southwest corner. It flows northeastward across the county and leaves at a point about 3 miles south of the northeastern corner. From there it flows a short distance eastward and then northeastward to a point about 10 miles south of Arkansas river in northern Grant county, where all traces of it gradually disappear. During times of heavy rains in southeastern Colorado and western Kansas, Bear creek carries a large quantity of water that is poured out on the plains in northern Grant county and into the sand hills south of Arkansas river. George S. Knapp, chief engineer of the Division of Water Resources, Kansas State Board of Agriculture, reports (personal communication) that—

At times when Bear creek carries an unusually large quantity of water, the stream overflows to the south, the water going into Cimarron river near Ulysses.

The waters from Bear creek have never been known to reach Arkansas river. Some of the residents believe that an underground stream extends from Bear creek beneath the sand hills to the Arkansas valley. This, however, was disproved by Slichter (1906, pp. 20-21), who in 1904 established three underflow stations south of Arkansas river east of Hartland to determine whether or not there was any seepage from the direction of Bear creek toward the Arkansas valley. He found that—

No ground water reaches either Clear lake or Arkansas river from the lost waters of Bear creek. Any seepage water approaching Arkansas valley from Bear creek must take up a generally easterly movement almost immediately upon entering the sand hills.

In the southwestern part of Stanton county Bear creek has cut a deep, locally steep-sided valley through the Ogallala formation, exposing the underlying Cockrum sandstone. In the northeastern part of the county the valley of Bear creek is shallow and in places almost unrecognizable. The average gradient of Bear creek as it crosses the county is about 9 feet to the mile. Little Bear creek follows closely the south side of the ridge in southern Hamilton county and enters Bear creek in the northern part of Stanton county about 1 mile south of the county line. A small area in the northwest part of the county is drained by an unnamed tributary of Little Bear creek.

Sand arroyo enters the county about 1 mile north of the southwest corner, flows in an easterly direction across the county, and leaves at a point about 7 miles north of the southeast corner. In the western part of its course it has cut a conspicuous, deep valley, but like Bear creek, through most of its course its valley is shallow and inconspicuous. After leaving Stanton county Sand arroyo joins North Fork of Cimarron river in southern Grant county. North Fork of Cimarron river crosses the extreme southeastern corner of Stanton county in a narrow but prominent valley.

Plate 3—A, Flat, featureless topography typical of the upland plains of Stanton county. View looking east from a point in sec. 10. T. 28 S., R. 41 W. B, Abandoned farm in Morton county, Kansas. Scenes like this are common in Stanton county. Note how the accumulated dust has almost completely buried the fence. Photograph by S. W. Lohman.

A belt of dune sand about 19 miles long and as much as 2.5 miles wide extends along the south side of Bear creek in the central part of the county. The accumulated sand forms moderate slopes and hills that are separated by small basins. Some of the hills stand 40 feet or more above the depressions. In general, the area covered by dune sand has a more hilly or rolling surface than the surrounding land.

Population

In 1940 Stanton county had the fewest residents of any county in the state. The population of the county has fluctuated greatly since the first census was taken. The population in 1890 was 1,031; in 1900, 327; in 1910, 1,034; in 1920, 908; and in 1930, 2,152.

According to the 1940 census it was 1,443, an average of 2.1 persons to the square mile. Johnson City, the county seat, which is situated in the middle of the county, had a population of 524 in 1940, and Manter, located about 9 miles southwest of Johnson City, had a population of 133. Population figures are not available for Big Bow and Saunders. Big Bow is a small, unincorporated community in the east-central part of the county. Saunders, located near the state line in the southwestern part of the county, serves as a supply station for farmers and is a grain-shipping point. Early maps of the county show several small communities that have since been abandoned, including Fisher, Floto, and Fletcher.

Transportation

Stanton county is served by a branch line of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe railway, which runs from Dodge City through Satanta to Prichett, Colo. It passes through all the communities in the county-Big Bow, Johnson City, Manter, and Saunders.

U. S. highway 160 passes from east to west through the middle of the county. It is graveled from Johnson eastward, but is not graveled west of Johnson. State highway 27 traverses the middle of the county from north to south and is graveled throughout. U. S. highway 270 follows state highway 27 from the north county line to Johnson and from there it follows U. S. highway 160 eastward. The highways and main county roads are kept in good condition and are passable throughout the year. Part of the county roads and section-line roads become temporarily impassable at different times of the year owing to drifting sand, snow, or mud, but in general the roads are good throughout the year and travel is not thus impeded.

Agriculture

Stanton county was first settled by ranchers in the latter part of the nineteenth century because of the good grazing land and the abundant supply of good stock water. There was very little cultivation at first and such cultivation was chiefly incidental to the raising of livestock. After a time ranches gradually gave place to wheat farms, so that now there are no large cattle ranches left in the county. The most extensive farm development came after the World War, owing mainly to the large increase in the price of grain. In 1935, 74.4 percent of the total area of the county was under cultivation and only 14.1 percent was being used for pasture (Joel, 1937, p. 16). The principal crops grown in Stanton county in 1935 were as follows (Joel, 1937, p. 65):

| Crop distribution in Stanton county in 1935 | |

|---|---|

| Acres | |

| Wheat | 97,787 |

| Hay and forage | 7,876 |

| Grain sorghum | 3,721 |

| Barley | 948 |

| Corn | 116 |

Since farming has been undertaken in the county, crop failures have been more common than crop successes, and each year since 1932 the county has experienced partial or complete crop failure. The chief causes of crop failure have been drought and wind erosion. Joel (1937, p. 14) states that the wind erosion was not serious until overgrazing depleted the native vegetation or cultivation destroyed it; that there was little wind erosion during extremely dry periods of the past such as that of 1893-'95. In the last 8 or 10 years the intensity and frequency of dust storms has become an extremely serious problem not only in Stanton county, but over the entire High Plains region.

Crop failures, the result of drought and wind erosion, along with lowered grain prices, have forced many farmers to abandon their farm homes (pl. 3B) and to live in other parts of the country. For those who remained these factors have resulted in a general lowering of the standards of living and in the necessity of government assistance. Almost half the farms in Stanton county are now worked by tenants and it is not uncommon to find several farms being worked by the same man. The average size of the farms has increased so that today the average farm consists of 845.3 acres (Joel, 1937, p. 66). Schoff (1939, p. 35), in writing about Texas county, Oklahoma, states that the increase in the size of farm units has been due to "the uncertain crop yield from year to year" and to "the flatness of the plains, which favors economical operation of large acreages by the use of tractors."

In summary, wheat raising is the chief industry of the county and only a small percentage of the land is devoted to the raising of cattle. Owing to low rainfall, paying crops are not raised every year, and the farmers have become accustomed to experiencing several crop failures for every good crop.

Climate

The climate of Stanton county is the semiarid continental type involving slight precipitation, moderately high average wind velocity, and rapid evaporation. During the summer the days are hot, but the nights are, as a rule, cool and comfortable. The heat of the hot summer days in this part of the state is more easily endured than the heat in the eastern part of the state, owing to the lower relative humidity in the west. During most of the winter the weather is moderate and there are only occasional short severe cold periods. The average mean annual temperature at Johnson is 54.T F. The average growing season, that is, the average interval between the last killing frost in the spring and the first killing frost in the fall, is about 17.6 days, and has ranged from a minimum of 156 days in one year to a maximum of 204 days in another year.

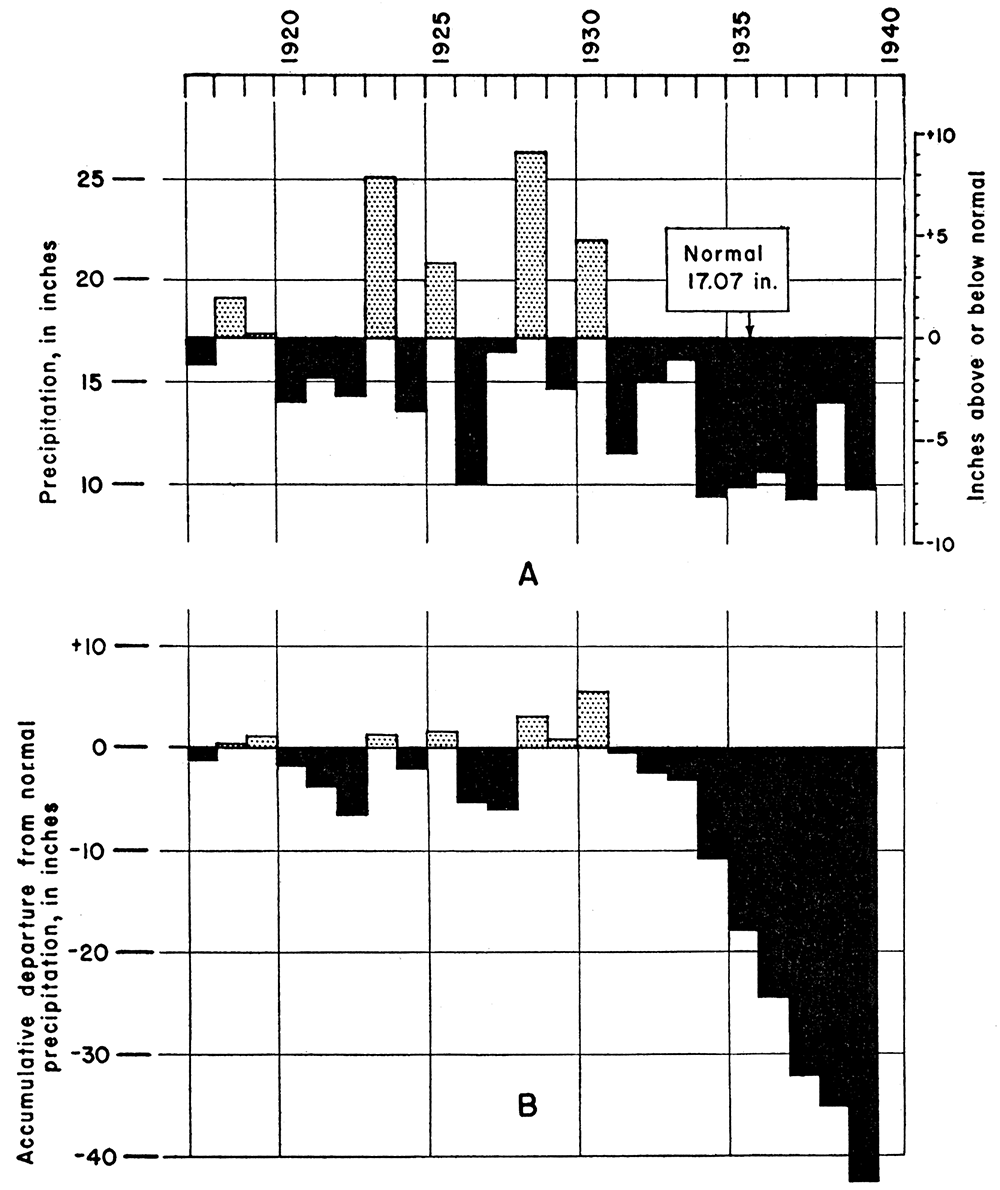

Figure 2—Graphs showing (A) the annual precipitation at Johnson, Kan., and (B) the accumulative departure from normal precipitation at Johnson.

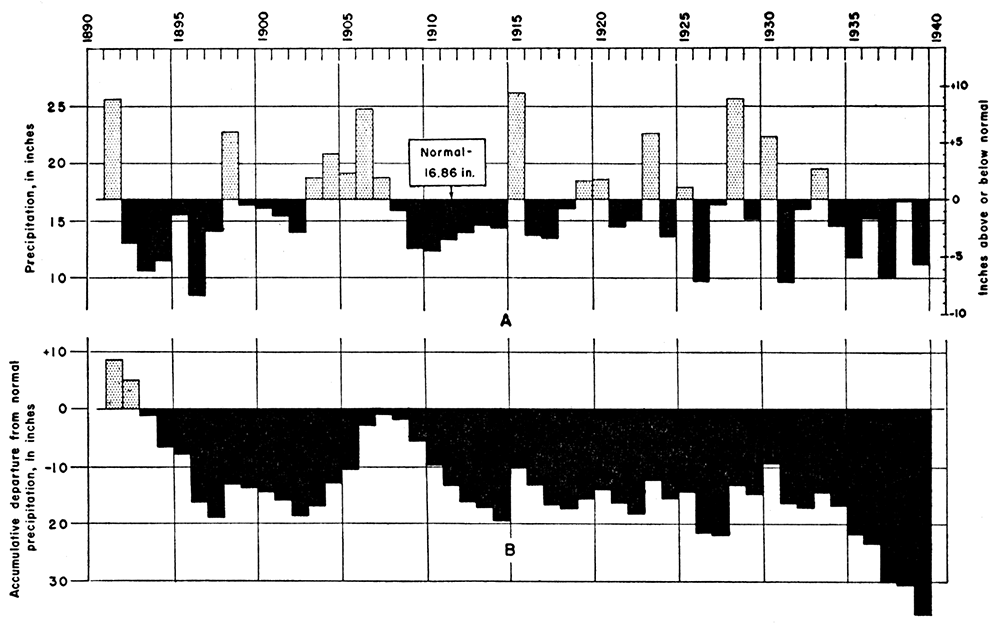

A large proportion of the moisture falls as torrential rains that are separated by long intervals of dryness. Most of the rain falls in the crop-growing season, which extends from March to September. The average mean annual precipitation at Johnson is 17.07 inches, and at Ulysses in Grant county it is 16.86 inches. The rainfall at Johnson has been below normal every year for the last 9 years. The annual precipitation and the accumulative departure from normal precipitation at Johnson and Ulysses are shown graphically in figures 2 and 3.

Figure 3—Graphs showing (A) the annual precipitation at Ulysses, Grant county, Kansas, and (B) the accumulative departure from normal precipitation at Ulysses.

Prev Page--Introduction || Next Page--Geology

Kansas Geological Survey, Geology

Placed on web Oct. 5, 2018; originally published November 1941.

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

The URL for this page is http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/Bulletins/37/03_geog.html