Prev Page--Classification || Next Page--Summary

Stratigraphy

Desmoinesian Series--Cherokee Group

Venteran Substage-Krebs Subgroup

The Krebs subgroup (Oakes, 1953) includes the Hartshorne sandstone and the McAlester, Savanna, and Boggy formations in the type area in southeastern Oklahoma. Thus, the division extends from the base of the Hartshorne sandstone upward to the top of the Seville (Inola) limestone. The above-named units are terms applied to the thick basin deposits of Venteran age by Oklahoma geologists, and their stratigraphic boundaries do not coincide with those of formational rank in areas to the north, which may be regarded as shelf areas. The Hartshorne sandstone is not recognized in northern Oklahoma, southeastern Kansas, or Missouri. The Krebs thins northward to only a fraction of its thickness in the basin, but except for the Hartshorne sandstone is regarded as being completely represented in southeastern Kansas. The southward thickening of Cherokee rocks in Oklahoma is illustrated by Figure 7.

Figure 7--Diagram illustrating southward thickening of pre-Marmaton Desmoinesian rocks from shelf area in northern Oklahoma to McAlester basin. (Modified from unpublished chart prepared by R. H. Dott, 1951.)

Throughout the region the Krebs subgroup is characteristically much more clastic than the overlying Cabaniss and Marmaton. The Krebs succession includes much less limestone, but in general clay-ironstone is abundant in dark shaly portions.

In the outcrop area in southeastern Kansas, the Krebs includes only three coal beds (Riverton, Rowe, and Dry Wood) that are of minable thickness. Two prominent sandstones are present. The Seville limestone and the underlying thin coal (Bluejacket) are absent in most places; accordingly, for practical purposes, the top of the Bluejacket sandstone may be regarded as the upper boundary of the group (Pl. 1).

Exposures showing the succession between the Bluejacket sandstone and the base of the subgroup are uncommon, except where coals in the upper part of the group have been mined and associated strata are uncovered. The Warner sandstone and lower beds locally may be seen along streams and in sinkholes. Accordingly, it is not possible to describe the Krebs in as much detail as the overlying Cabaniss subgroup.

Searight and others (1953) defined the following Krebs formations: Riverton (beds above rocks of Mississippian or pre-Desmoinesian Pennsylvanian age and below the top of the Riverton coal); Warner (beds above the Riverton coal, including the prominent Warner sandstone, and extending upwards to the top of the Neutral coal); Rowe (beds above the Neutral coal and below the top of the Rowe coal); Dry Wood (beds above the Rowe coal and including the Dry Wood coal at the top); Bluejacket (beds above the Dry Wood coal, including the Bluejacket sandstone, and extending upwards to the Seville limestone); and the Seville (including only the Seville limestone).

The Bluejacket formation includes at least one coal bed above the Dry Wood coal and below the Bluejacket sandstone. Coal in this sequence is extremely erratic in its distribution, and no single coal horizon can be traced in western Missouri or in southeastern Kansas. [Note: The term coal horizon is used in this report to indicate the position in stratigraphic sequence at which coal would be expected if the sedimentary cycle were completely represented by sediments. The position may be indicated by a film of carbonaceous matter or unusual concentration of carbonaceous matter in rocks of other lithology.] Accordingly, no name has been applied to such coal or coals, and they are included within the Bluejacket formation. A well-defined coal horizon lies just above the Warner sandstone and probably is to be correlated with an unnamed coal at this position (Wilson and Newell, 1937, p. 37-39) in eastern Oklahoma. The average thickness of the Krebs in the outcrop area in southeastern Kansas is between 200 and 250 feet. The subgroup is somewhat thinner in western Missouri, but thickens southward in northeastern Oklahoma, increasing tremendously south of T. 13 N., toward the McAlester basin. In the vicinity of McAlester, Oklahoma, this succession is reported to be more than 10,000 feet thick (Wilson and Newell, 1937, p. 19). The Krebs comprises about half of the pre-Marmaton Desmoinesian section in southeast Kansas, but it becomes so thick toward the south that it represents about 75 per cent of this section in the McAlester basin (Fig. 7).

Because of the complexity of the stratigraphy and nomenclature of the sub-Bluejacket coal beds in Kansas and Missouri, Walter V. Searight, of the Missouri Geological Survey, and the writer have worked in close cooperation in an attempt to avoid addition of unnecessary names in this succession. The coal beds are exceptionally variable, and many names have been applied to them, both in Kansas and in Missouri. The uppermost of the Krebs coal beds found to be laterally persistent is the Dry Wood, named from its occurrence in a tributary to Dry Wood Creek in the NW SE NE sec. 4, T. 33 N., R. 33 W., Barton County, Missouri. The Rowe coal (Pierce and Courtier, 1937, p. 65) is the most extensively mined bed between the Warner and Bluejacket sandstones, and occurs below the Dry Wood. It is characterized locally by a fossiliferous cap-rock limestone. In central and southern Cherokee County, an additional coal bed is found below the Rowe coal and above the Warner sandstone. This coal, which is overlain by a thin bed of ferruginous limestone, is not known north and east of central Cherokee County in Kansas, but may be present in Barton County, Missouri. A thin impure limestone or clay-ironstone bed in northeastern Cherokee County probably represents the ferruginous limestone. The coal bed next below the Rowe in central Cherokee County is the Neutral. The formations constituting the Krebs subgroup, as developed in southeastern Kansas, are described in ascending order.

Riverton Formation

Definition and subdivisions--The Riverton formation (Searight and others, 1953) includes all lower Desmoinesian beds below the top of the uppermost of the Riverton coal beds, from which the formation takes its name. The name Riverton was originally applied (Pierce and Courtier, 1937, p. 62) to the coal bed between the Warner (Little Cabin) sandstone and the underlying Mississippian rocks in southeastern Cherokee County. It is now known that two somewhat irregular coal beds separated by clay occur at this position in southeastern Kansas and adjacent parts of western Missouri. It has not been possible to differentiate these beds with sufficient certainty to allow identification in an exposure where only one coal is present. Accordingly, for the purposes of this report, the Riverton coal is recognized as being composite. The Riverton formation comprises three distinct units; dark fissile shale at the base, underclay, and Riverton coal at the top. In all exposures observed in Cherokee County, the basal dark shale lies on leached chert rubble derived from underlying Mississippian rocks. The latter material is the basal Pennsylvanian "chat" of drillers in southeastern Kansas. The best exposures of the Riverton formation occur along tributaries of Spring River and in sinkholes in eastern Cherokee County. In sinkholes (Pl. 3A), where the strata are commonly faulted, owing to slumping or collapse, the basal shale and higher exposed beds contain masses of euhedral pyrite and marcasite crystals. These sulfides are most abundant along joints and fault planes, and were probably introduced after collapse of caverns in the underlying Mississippian limestone. It is apparent that the lowermost Pennsylvanian sediments in this area were deposited on a surface of relatively low relief, and that the caverns were formed and collapsed after consolidation of those sediments.

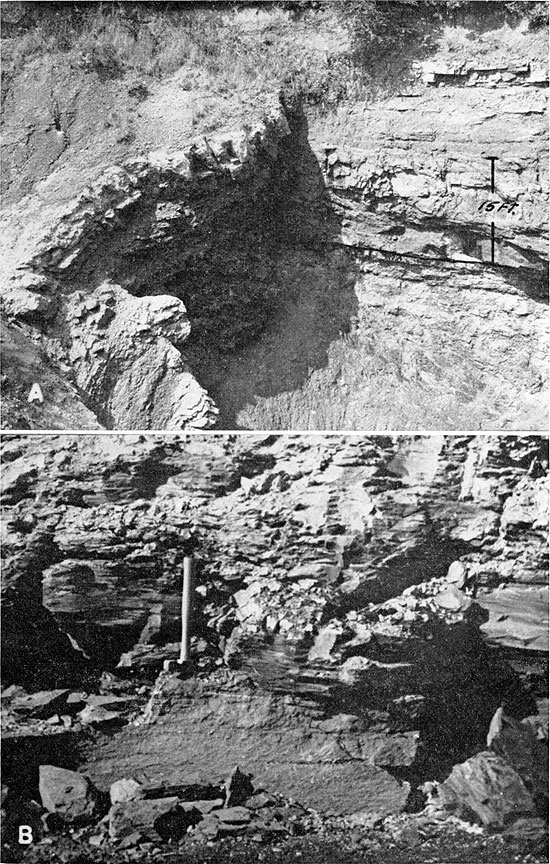

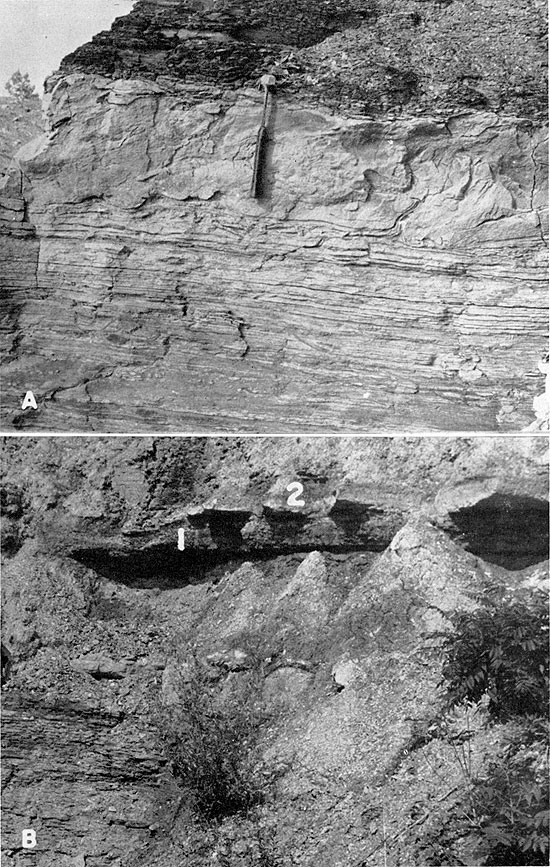

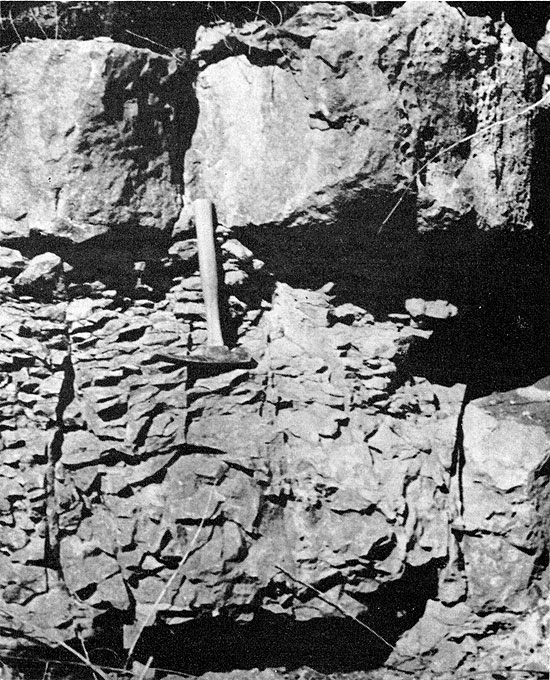

Plate 3--A. Sinkhole exposure of Riverton and lower part of Warner formation, SW NE sec. 9, T. 32 S., R. 25 E., Cherokee County. Massive bed above line is coarsely cross-bedded Warner sandstone. Riverton coal is just below line. B. Caprock limestone of Rowe coal (below hammer head), NE SW sec. 12, T. 32 S., R. 24 E., Cherokee County.

The Riverton formation, as presently defined, is in part equivalent to the McCurtain shale (Wilson, 1935, p. 508) of eastern and southeastern Oklahoma. The coal beds in the formation may be correlated tentatively with the upper Hartshorne coal of Oklahoma.

The thickness of this basal formation of the Krebs subgroup in Kansas ranges from 10 to 20 feet, and averages about 15 feet.

Basal shale--Dark-gray to black fissile shale ranging in thickness from 4 or 5 feet to an observed maximum of 13 feet forms the lowermost division of the Riverton formation in Kansas. The chert rubble of Mississippian age beneath this shale ranges in thickness from a few inches to several feet. No fossils have been observed in this shale unit. The upper part is commonly leached to medium or light gray.

Underclay--The Riverton coal is underlain by medium- to light-gray underclay, which is hard and tough. The clay contains fossil root impressions and also disseminated carbonized plant material. Thickness of this unit ranges from 2 to 4 feet.

Riverton coal--The Riverton coal (Pierce and Courtier, 1937, p. 62) is the uppermost unit of the Riverton formation. At least two coal beds separated by clay are known at this position. For the purposes of this report, and in regional classification (Searight and others, 1953), they are not separately named, because of the difficulty in identifying individual beds where only one is present, and because of their seemingly close genetic relation. The overlying Warner sandstone may rest upon the shale over the upper coal, on the upper coal, on clay over the lower coal, or directly upon the lower coal. The upper coal, slightly more than 1 foot thick, has been mined locally in southeastern Cherokee County. In most outcrops the lower coal is indicated only by a thin streak, but it reaches a thickness of several inches in exposures in Jasper County, Missouri. The aggregate thickness of the Riverton coals, including intervening clay, probably averages about 2 feet in southeastern Kansas. The Riverton coal has never been commercially important in southeastern Kansas.

Warner Formation

Definition and subdivisions--The Warner formation (Searight and others, 1953) includes the beds above the Riverton coal extending upward to the top of the Neutral coal bed. The succession includes the prominent and widespread Warner (Little Cabin) sandstone (Wilson, 1935, p. 508; Wilson and Newell, 1937, p. 37-39), from which it takes its name. A coal horizon is present above the Warner sandstone, but as its relations are not clear at present, it is included within the Warner formation, and the Neutral coal is defined as the uppermost unit of the formation. An unnamed coal (Wilson and Newell, 1937, p. 37-38), is present just above the Warner sandstone in east-central Oklahoma, and the horizon noted above is probably its northward equivalent. Further detailed study of this succession in northeastern Oklahoma may substantiate this view, and if such correlation can be established, beds above it, extending upward to the top of the Neutral coal in southeastern Kansas, would be called the Neutral formation, following usage adopted at the Nevada conference (Searight and others, 1953). This unnamed coal above the Warner sandstone and below the Neutral coal would then receive the name Warner. Lithologic subdivisions of the Warner formation in southeastern Kansas include: shale above the Riverton coal and below Warner sandstone, Warner sandstone, fissile dark- to medium-gray shale containing clay-ironstone concretions and beds, underclay of the Neutral coal, and the Neutral coal. The Warner formation thickens southward in the outcrop area in southeastern Kansas. It is generally less than 50 feet thick in southwestern Vernon County and northwestern Barton County, Missouri, and is 50 to 100 feet thick in Cherokee County, Kansas. Inadequacy of exposures precludes exact determination of thickness. Available well logs are not sufficiently detailed to show the position of the Neutral coal bed and are likewise of no value for determining exact thickness of the formation as defined. Logs indicate that locally the Warner sandstone rests on the surface of the Mississippian rocks and that the next lower formation (Riverton) is absent.

Shale between the Riverton coal and Warner sandstone--Dark-gray shale is seen overlying the Riverton coal bed in a few exposures in southeastern Cherokee County. It is generally absent, however, owing to erosion prior to deposition of the Warner sandstone, which commonly rests on the upper surface of the coal. Thickness of the shale ranges from a featheredge to about 2 feet. No fossils have been found in the shale.

Warner sandstone--The Warner sandstone (Wilson, 1935, p. 508; Wilson and Newell, 1937, p. 37-39) is one of the most prominent lithologic units in the succession assigned to the Krebs subgroup. This sandstone was earlier called Little Cabin by Ohern (1914), but participants at the Nevada conference agreed to use the term Warner because of its wider usage. Studies by Wilson (1935), Renfro (1947), and Weidman (1932) indicate that the Warner is essentially continuous in outcrop from the type locality near Warner, in Muskogee County, Oklahoma, northward to the Oklahoma-Kansas line, thence northeastward across Cherokee County into western Missouri. In part it is probably represented in the Ozark area by the Graydon sandstone and conglomerate. The Warner sandstone is composed of fine- to medium-grained, angular to subrounded quartz sand, and generally abundant muscovite. In the few exposures in southeastern Kansas where the complete succession can be seen (Pl. 3A), the Warner consists of a lower, massive, coarsely cross-bedded portion, 10 to 15 feet thick, overlain by 5 to 10 feet of micaceous siltstone and sandy shale, which is overlain by about 5 feet of massive fine-grained sandstone. The upper portion is locally a stigmarian sandstone, containing roots and root casts, and is overlain by dark-gray to black shale. In one exposure, underclay occurs above the stigmarian sandstone and below dark shale. The upper surface of the Warner sandstone is regarded as a coal horizon, and coal at this position in east-central Oklahoma (Wilson and Newell, 1937, p. 37-38) is tentatively correlated with it. Stratigraphic sections 19 and 45 include detailed descriptions of exposures illustrating this relationship. Continuous-inclined bedding ("torrential bedding") is common in the lower portion of the Warner sandstone, and in general is inclined southward. The basal portion of the Warner very commonly contains fragments or molds of fragments of shale incorporated from underlying beds, forming a "blister" conglomerate. No exposures were observed in which the Warner rests upon rocks of Mississippian age. The Warner commonly is asphaltic in southeastern Kansas.

The "Burgess sand" of the subsurface in Kansas is probably equivalent to the Warner. Wilson (1935, p. 505) also correlated the "Booch" sandstone of the subsurface in Oklahoma with the Warner.

The thickness of the Warner sandstone in the outcrop area in southeastern Kansas ranges from 10 to about 25 feet.

Dark shale above the Warner sandstone--Several isolated exposures in southeastern Kansas indicate that the rocks between the Warner sandstone and Neutral coal consist of dark- to medium-gray fissile shale, containing abundant clay-ironstone, present both as isolated concretions and as well-defined beds or layers. This succession, although much condensed, represents the bulk of the McAlester formation of east-central and southeastern Oklahoma. In the upper part of the succession, wen exposed along Brush Creek in the NE SW sec. 10, T. 34 S., R. 24 E., Cherokee County, at least two well-defined clay-ironstone zones are underlain by poorly developed underclays, and may represent coal and limestone beds (Spaniard or ?Sam Creek) present in eastern Oklahoma, where this portion of the Warner formation thickens markedly.

The thickness of the Warner sandstone-Neutral coal sequence ranges from a few feet in northeastern Crawford County (based upon exposures in adjacent Vernon and Barton counties, Missouri) to an estimated 70 feet in central and southern Cherokee County.

Underclay--Scattered exposures in the vicinity of Neutral, in central Cherokee County, indicate that the Neutral coal is underlain by underclay having an average thickness of about 2 feet.

Neutral coal--The name Neutral was originally applied by Abernathy (1936, p. 74-75; 1938, p. 196) to a succession containing two coal beds, which he identified as parts of a cyclothem. These coal beds seemingly are the upper two of three distinct coal beds between the Warner and Bluejacket sandstones in the vicinity of Neutral. The lower of these two is the Rowe coal, and the upper is the Dry Wood coal. The name Neutral is here redefined and restricted so as to apply to the lowermost of the three coal beds present in that locality. Stratigraphic section 20 describes the exposure designated as typical, located along Brush Creek in the NE SW sec. 10, T. 34 S., R. 24 E., a short distance east of the town of Neutral. In this vicinity the coal attains its maximum known thickness of 6 inches. Its stratigraphic position has been tentatively identified in northeastern Cherokee County (stratigraphic section 44), but the bed itself has not been identified positively in the outcrop area north and east of Neutral either in Kansas or in western Missouri. The Neutral coal is characterized in the type area by an extremely ferruginous cap-rock, which is classed as the lower portion of the overlying Rowe formation and is discussed along with other units in that formation. The Neutral coal is not known to have been mined in southeastern Kansas. It is possibly equivalent to the "Lower Boggy" coal (Wilson and Newell, 1937, pl. 3) of eastern Oklahoma.

Rowe Formation

Definition and subdivisions--The Rowe formation (Searight and others, 1953) includes beds above the Neutral coal and extends to the top of the Rowe coal (Pierce and Courtier, 1937, p. 65). The formation takes its name from the Rowe coal, which has been the most extensively mined sub-Bluejacket coal in southeastern Kansas and western Missouri.

Because of insufficient exposures it is not possible to describe precisely the complete succession of beds that constitute the Rowe formation. The Rowe coal bed itself is widespread, and its thickness and general character are relatively well known, owing to extensive mining. The lower part of the formation includes the distinctively ferruginous limestone cap-rock of the underlying Neutral coal. Recognized divisions of the Rowe are described in the following paragraphs.

Lowermost limestone--In the type area of the Neutral coal and elsewhere in Cherokee County, this coal is overlain by a 3- to 6-inch impure limestone or clay-ironstone bed containing coquinoidal layers of detrital shell material. This bed ranges from essentially unfossiliferous clay-ironstone to impure fossiliferous limestone so rich in iron that it weathers to impure hematite and limonite. It is the most persistently fossiliferous bed in the Krebs subgroup in southeastern Kansas. Limestone above the Rowe coal attains greater thickness, and is less impure, but is characteristically lenticular and very erratic in distribution. Most fossil material in the lower Rowe bed is detrital and associated with fragments of fusain. Locally, however, fossils are abundant in the form of external and internal molds, the shell material having been dissolved, and the matrix altered to limonite and hematite. Insoluble residue from a sample of this bed at a locality where a small quantity of fossil material was observed amounted to only about 5 percent, consisting chiefly of silicified shell fragments and some very fine subangular to rounded quartz sand. This bed is tentatively identified in northeastern Cherokee County (stratigraphic section 44), where it is represented by clay-ironstone. Identification at this place is based upon similarity of lithologic succession. The Neutral coal is absent; underclay regarded as that belonging next below the Neutral coal lies directly under the clay-ironstone. The limestone is present south and east of Columbus, in the vicinity of Neutral (stratigraphic section 20), and is probably represented in northern Oklahoma by the limestone called Elm Creek (Weidman, 1932, p. 25-26) and Doneley (Chrisman, 1951; Branson, 1954, p. 192). It seemingly corresponds to the cap-rock of the Lower Boggy coal of Wilson and Newell (1937, p. 53) in east-central Oklahoma. In the field this bed has been given the name "Red lime" because of its characteristically red or reddish-brown color. It is underlain by the Neutral coal and overlain by dark fissile shale. No formal name has been applied to this persistent bed in Kansas, as it is judged that future work will establish correlation with the Doneley limestone in northern Oklahoma. The term Elm Creek (Weidman, 1932, p. 25-26) has been abandoned (Claxton, 1952, p. 7) because of its older usage for other beds.

Fossils from the cap-rock of the Neutral coal include very abundant Derbyia crassa, Marginifera cf. ingrata or nana, and Neospirifer cameratus. Composita subtilita is common; Aviculopecten?, Astartella, Spirifer occidentalis, and crinoid elements occur locally. A group of small, possibly depauperate, snails and clams is associated with the other forms. Bone and tooth fragments are locally present.

Beds between the limestone and Rowe coal--The sequence between the basal limestone of the formation and the Rowe coal is known from only a few scattered outcrops in southeastern Kansas. The only complete exposure known to me is along Brush Creek, in the NE SW sec. 10, T. 34 S., R. 24 E., Cherokee County (stratigraphic section 20). The available data indicate that the succession includes dark-gray to black fissile shale 5 to 10 feet thick, overlain by 2 or 3 feet of underclay. The dark shale contains several layers of clay-ironstone having a maximum thickness of 4 inches. Slumped and partly covered outcrops in eastern Cherokee County indicate that part of this section, the "12-foot" sandstone (field term used by geologists in Craig County, Oklahoma), seemingly lies either at this position or in the overlying Dry Wood formation.

Rowe coal--The Rowe coal (Pierce and Courtier, 1937, p. 65), named for its occurrence in the vicinity of Rowe School in eastern Crawford County (sec. 34 and 35, T. 30 S., R. 25 E.), is economically the most important coal bed within the Krebs subgroup in southeastern Kansas and western Missouri. It has been mined extensively by stripping in the area south and east of Pittsburg, in Crawford County; east of Weir City in northeastern Cherokee County; east and south of Columbus, and in the vicinity of Neutral, in central Cherokee County. It is the lower of the two coal beds included in the "Neutral cyclothem" of Abernathy (1936, p. 74-75; 1938, p. 196), and is the bed called "Columbus" and mined near that town. The "Bellamy" coal (Greene and Pond, 1926, p. 46), which actually includes two distinct coal beds, is in part equivalent to the Rowe.

The Rowe coal ranges in thickness from about 10 inches to a maximum of 20 inches, and is commonly 15 to 18 inches thick. It is characteristically blocky, and is reported by users to be of good quality. A thin clay parting in this bed was reported by Pierce and Courtier (1937, p. 65), and regarded by them as characteristic. A clay parting less than 1 inch thick is present in it near Neutral but was not noted in the several mines operating on this bed in northeastern Cherokee County. The Rowe is characterized by a limestone cap-rock, which, in contrast to the relatively persistent one above the Neutral coal, is lenticular and extremely erratic in its distribution. It properly belongs within the Dry Wood formation and is described as a part thereof.

The Rowe coal bed has been a relatively minor source of coal production in southeastern Kansas.

Dry Wood Formation

Definition and subdivisions--The Dry Wood formation (Searight and others, 1953) includes beds between the top of the Rowe coal and the top of the Dry Wood coal. The formation is somewhat variable in thickness and in lithology. The coal bed (Dry Wood) included in the formation has been mined only locally, and is characteristically irregular. In northeastern Cherokee County the formation includes a lenticular limestone, which lies next above the Rowe coal. The Dry Wood formation includes the following recognized divisions in upward order: basal dark shale containing lenticular limestone, thin irregular silty limestone and clay-ironstone, underclay, and the Dry Wood coal. The formation thickens from 6 or 8 feet in southeastern Crawford County to a maximum of somewhat more than 15 feet in central and southern Cherokee County.

Dark shale--Dark-gray to black fissile shale composes the lower part of the Dry Wood formation. This unit commonly contains thin beds and small isolated concretions of clay-ironstone, and weathers light gray, forming thin brittle chips. Thickness ranges from 3 or 4 feet in the northern part of the area of outcrop to slightly more than 10 feet in central and southern Cherokee County.

Locally, massive lenticular limestone is found at the base of the unit, lying just above the Rowe coal. This limestone, which, because of its seemingly local occurrence has not been named, is dark gray to black, carbonaceous, and ranges from compact crystalline rock (Pl. 3B) to very impure shaly limestone. Its thickness ranges from a featheredge to about 30 inches. This bed is extremely fossiliferous, and is composed principally of organic debris. Fossils include locally very abundant Spirifer occidentalis, Composita subtilita, Derbyia crassa, Linoproductus sp., Prismopora triangulata, crinoid plates and columnals, Orbiculoidea capuliformis, Fenestrellina sp., Rhombopora sp., and Punctospirifer kentuckyensis. Fish teeth, especially those assigned to the genus Petalodus, and bone fragments are locally very abundant. Limestone in the basal part of the Dry Wood formation is known only in a few localities in northeastern Cherokee County. Branson (1954, p. 192) tentatively correlated the Doneley limestone of Oklahoma with this bed, but it seems more likely that the Doneley overlies the Neutral coal.

Silty limestone and clay-ironstone--Most exposures of the Dry Wood formation, including that at the type locality, in a tributary to Dry Wood Creek in northwestern Barton County, Missouri, reveal the general presence of silty limestone or very impure clay-ironstone above the lower shale and below the underclay division of the formation. This unit is very irregular in lithology, and averages somewhat less than 1 foot in thickness. It occupies the position and has many of the characteristics of the underlimestones commonly associated with the underclays of coal beds in the overlying Cabaniss subgroup. In natural exposures this material weathers to reddish-brown, sintery or porous silt and clay. No fossils, other than worm trails, are known from it in the area of this report.

Underclay--Underclay associated with the Dry Wood coal ranges in thickness from about 2 feet to an observed maximum of 5 feet. This bed contains fossil plant material and root impressions throughout, even where it is thickest.

Dry Wood coal--The Dry Wood coal is extremely irregular in thickness and quality, and has not been mined extensively in southeastern Kansas. It is equivalent in part to the "Bellamy" coal of western Missouri (see Rowe coal). This bed seemingly has been mined only locally in southeastern Crawford County and northeastern Cherokee County, and is the uppermost of the two coal beds formerly mined in the vicinity of Neutral. It is directly overlain by the Bluejacket sandstone in many places and is commonly deeply weathered or leached. The Dry Wood is seemingly the uppermost coal bed included in the "Neutral cyclothem" of Abernathy (1936, p. 78-79; 1938, p. 196). Thickness of the Dry Wood coal ranges from a featheredge to 20 inches, but in most places is 3 to 8 inches.

Bluejacket Formation

Definition and subdivisions--The Bluejacket formation includes beds directly above the Dry Wood coal and extending to the top of the Bluejacket coal (Searight and others, 1953). The succession includes the prominent and well-known Bluejacket sandstone (Ohern, 1914, p. 28-29; Howe, 1951, p. 2088-2091), from which the formation takes its name. The Bluejacket coal has been identified at only one locality in southeastern Kansas (abandoned clay pit, sec. 28, T. 30 S., R. 25 E., Crawford County). At this place the coal is represented by a thin smut. Elsewhere in southeastern Kansas both this bed and the overlying Seville limestone seem to be absent and the upper unit of the Bluejacket formation is the Bluejacket sandstone, which directly underlies the thin Bluejacket coal or, where the succession is complete, its underclay.

Divisions of the Bluejacket formation in southeastern Kansas include, from the base upward: sandy shale over the Dry Wood coal, Bluejacket sandstone, and Bluejacket coal with its associated underclay. The Bluejacket sandstone is the most widespread of these units in the Oklahoma-Kansas-Missouri area. The thin coal forming the upper member of the formation is of very limited extent in Kansas.

Lower shale and sandy shale--The Dry Wood is the highest sub-Bluejacket coal bed having appreciable lateral extent in the area of this report. Between it and the base of the Bluejacket sandstone lie shale and sandy shale (Pl. 4A). This shale locally contains a thin, seemingly nonpersistent coal, which is included within the formation because it is judged not to be of sufficient thickness or lateral extent to merit separate description. The thickness of the shale unit is at most only a few feet; commonly the Bluejacket sandstone rests on an erosion surface developed at or about the position of the Dry Wood coal, higher sub-Bluejacket beds being absent.

Plate 4--A. Dry Wood coal and base of Bluejacket sandstone (dashed line), SW sec. 12, T. 32 S., R. 24 E., Cherokee County. Rowe coal was mined here. B. Weir-Pittsburg (1) (below hammer head) and Tebo coal (2) beds, NW sec. 25, T. 32 S., R. 23 E., Cherokee County. Light-colored bed (3) above hammer handle is Tiawah limestone. Photograph by A. L. Hornbaker.

Bluejacket sandstone--The Bluejacket is the uppermost sandstone unit in the Krebs subgroup in northern Oklahoma, southeastern Kansas, and Missouri. In southeastern Kansas, the Bluejacket sandstone forms the uppermost unit of the Krebs except in the limited area where the overlying Bluejacket coal and underclay can be identified (see Bluejacket coal).

The Bluejacket was originally described by Ohern (1914, p. 28-29). Howe (1951, p. 2088-2091) revised Ohern's definition, because the locality designated by Ohern as typical included several sandstone beds separated by shale and coal beds, and usage had not been consistent. The original designation of the type locality included conglomeratic sandstone now regarded as Chelsea above the Bluejacket (restricted) and the "12-foot" sandstone (field term of Oklahoma geologists) below it. According to Carl C. Branson, of the University of Oklahoma (quoted in Howe, 1951, p. 2090), the "12-foot" sandstone originally was mapped as Bluejacket by Ohern in the vicinity of Bluejacket, Vinita, and Whiteoak, Oklahoma, but in areas farther south the Bluejacket sandstone as now restricted was mapped. The definition and designation of the type section of the Bluejacket was revised so as to include the sandstone regarded by both the Oklahoma and Kansas Geological Surveys as true Bluejacket. This sandstone commonly is regarded as equivalent to the "Bartlesville" sand of the subsurface.

The Bluejacket sandstone can be traced along virtually all of the outcrop in southeastern Kansas, and it is present in western Missouri. It is extensively exposed in the vicinity of Columbus, central Cherokee County, and east to Pittsburg, eastern Crawford County. Topographically, it forms a cuesta, which is variable in prominence, principally owing to variation in thickness. In central and southern Cherokee County, the Bluejacket sandstone caps several outliers and buttes such as the Timbered Hills and prominent Mounds near Treece, just north of the Kansas-Oklahoma line. Pierce and Courtier (1937, pl. 1) indicated the presence of the Bluejacket sandstone in Cherokee County, but did not map it as far northeast as Weir City. There seems no valid reason for not extending recognition of this unit across Cherokee County and southeastern Crawford County, Kansas, into Barton County, Missouri. It is somewhat thinner in the north, possibly because of the development of the Pittsburg anticline, but the succession of coal beds beneath it is similar throughout the region.

The Bluejacket sandstone rests unconformably on lower beds, but the surface of unconformity seemingly has a maximum relief of only 10 or 15 feet in the area of this report. The Dry Wood coal locally is absent, owing to pre-Bluejacket erosion.

The Bluejacket is composed principally of fine- to medium-grained, micaceous, angular to subangular quartz sand, but includes minor amounts of very fine sand and silt. It is a well-sorted deposit, for sieve analyses of samples from several. exposures indicate that 50 to 60 percent of the sand passes the 60-mesh and is caught on the 100-mesh (Tyler) screen (fine sand of Wentworth classification), and progressively smaller amounts are included in the finer sizes. A "blister" conglomerate, formed of fragments of clay-ironstone concretions and shale, commonly is present in the basal part of the member. The conglomeratic material is seemingly all of local origin. Bedding in the Bluejacket member ranges from nearly flat bedding to steeply inclined cross-bedding. Layers of cross-bedded sandstone are set off from similar cross-bedded sandstone both below and above by almost horizontally bedded sandstone. This type of cross-bedding is particularly common where the Bluejacket sandstone is thick, as in exposures along Neosho River near the Kansas-Oklahoma state line. It is also found in the asphaltic sandstone quarry at Iantha, in Barton County, Missouri. Steeply inclined cross-bedding of this type (continuous incline-bedding of Pettijohn, or "torrential bedding") is best developed where the member is 20 feet thick or more. In most of the area of Bluejacket outcrop, cross-bedding is much less pronounced, and the rock is slabby or thin bedded to massive. In southeastern Crawford County, the upper part is locally shaly. In outcrop the Bluejacket weathers tan to brown or reddish brown.

The Bluejacket sandstone increases in thickness to the south in the outcrop area in southeastern Kansas. It is 10 to 15 feet thick in western Barton County, Missouri, and eastern Crawford County and northern Cherokee County, Kansas, but 20 to 30 feet thick in central and southern Cherokee County. It is about 40 feet thick along Neosho River near the Kansas-Oklahoma state line and in northern Craig County, Oklahoma.

The Bluejacket sandstone has been quarried for building stone in Cherokee County, and provides road-surfacing material at Iantha, in Barton County, Missouri, where it is extremely asphaltic. This member is most important economically as an oil reservoir in eastern Kansas.

Bluejacket coal--The Bluejacket coal (Searight and others, 1953) has been identified only tentatively at a single locality (abandoned clay pit, SW sec. 28, T. 30 S., R. 25 E., Crawford County) in Kansas, where it is represented by a thin smut. The Bluejacket coal is regarded as a correlative of the Rock Island No. 1 coal of western Illinois. It has been mined locally in the vicinity of Clinton, Henry County, Missouri and elsewhere in that state.

Seville Formation

The Seville formation, as defined in this area (Searight and others, 1953), includes only the Seville limestone (Wanless, 1931, p. 804-805). It is found in northern Barton County and southern Vernon County, western Missouri, but has not been recognized in southeastern Kansas except in a single locality near Pittsburg, in eastern Crawford County (abandoned clay pit, SW sec. 28, T. 30 S., R. 25 E.). At this place identification is tentative, being based mainly upon stratigraphic position. The limestone is very impure and has little resemblance to the Seville of western Missouri. Although fossiliferous, the bed does not contain the fauna characteristic of the Seville. It is judged that the bed identified as Seville near Pittsburg represents a unique facies of the Seville.

The Seville lies above the Bluejacket coal and below the underclay of the Weir-Pittsburg coal bed where the complete succession is present. This limestone, which here forms the uppermost unit of the Krebs subgroup, also crops out in Iowa and at various places in Missouri. Probably it is represented in Oklahoma by one of the several limestones called Inola, which are known only south of the latitude of Chelsea (Carl C. Branson, personal communication, May 5, 1953).

In southeastern Kansas, the bed tentatively identified as Seville is argillaceous and weathers to thin, irregular slabs. It is about 6 inches thick. Fossils observed include: Prismopora sp., Fusulinella? sp., Tetrataxis sp., and crinoid columnals. At localities in northwestern Barton County and southwestern Vernon County, Missouri, the limestone is characterized by Marginifera missouriensis, Mesolobus striatus, and Derbyia crassa.

Cygnian Substage-Cabaniss Subgroup

The Cabaniss subgroup (Oakes, 1953), in the type area situated in the McAlester basin in southeastern Oklahoma, comprises beds referred to the Thurman, Stuart, and Senora formations, which overlie the Krebs subgroup and occur below strata equivalent to the Marmaton group of the northern Midcontinent region. The Thurman and Stuart formations do not extend north of T. 13 N., because of northward overlapping by younger Cabaniss (Senora) deposits. In southeastern Kansas, the Cabaniss succession extends from the top of the Seville limestone to the base of the Blackjack Creek limestone, which is lower Marmaton.

The Cabaniss subgroup and overlying Marmaton deposits are included in the Cygnian Substage, because of continuity in the nature of the fauna, including particularly Marginifera muricatina and smooth forms of Mesolobus mesolobus; it is noteworthy also that as a whole this major division is characteristically somewhat less clastic (containing many prominent limestones) than the underlying Venteran Substage. Coal beds of the Cabaniss very commonly are characterized by association of underlimestones with their underclays, whereas such limestones are extremely uncommon in the Krebs.

The average thickness of rocks assigned to the Cabaniss subgroup in southeastern Kansas is about 200 feet. The succession is of comparable thickness in western Missouri and in Craig County, Oklahoma, but farther south in Oklahoma it increases in thickness. Although thickness of the Verdigris-Fort Scott sequence decreases considerably in northern Oklahoma, southward thinning of this portion of the Cabaniss is more than compensated by thickening of the pre-Verdigris Cabaniss beds. Such marked increase in thickness is especially noticeable in the shale between the Croweburg (Broken Arrow) coal and the Verdigris limestone.

In southeastern Kansas, and also in Missouri, the Cabaniss includes most of the minable coal beds, and is thus the most important coal-producing portion of the Pennsylvanian System in the two states.

A single prominent unconformity has been observed within the Cabaniss subgroup, at the base of the Chelsea sandstone; its local relief is about 30 feet in Cherokee and Crawford counties, but is much greater in northern Oklahoma, where the unconformity seems to be associated with faulting. In southeastern Labette County no beds between the Bluejacket sandstone and the Mineral coal (about 70 feet above the base of the Cabaniss) have been identified positively, and it is possible that the Chelsea and the Bluejacket together form the unusually thick sandstone previously regarded (Pierce and Courtier, pl. 1) as Bluejacket. The area is south of Chetopa, along Neosho River near the Kansas-Oklahoma line, and there erratic dips and faulting of the Pennsylvanian strata are common.

The Cabaniss is described in more detail than the underlying Krebs subgroup, for exposures are better and other sources of information are plentiful.

Weir Formation

Definition and subdivisions--The Weir formation (Searight and others, 1953) includes beds next above the Seville limestone and extends upward to the top of the Weir-Pittsburg coal (Haworth and Crane, 1898, p. 25-26). The name Weir had previously been applied by Abernathy (1938) to the cyclothem containing the Weir-Pittsburg coal. Searight and others (1953) modified the term by redefinition, and their usage is followed in this report.

The Seville limestone and the underlying Bluejacket coal are extensively exposed in northwestern Barton County and southwestern Vernon County, Missouri, but have not been observed in southeastern Kansas except in a clay pit at the east edge of Pittsburg. At this locality poorly developed limestone and an underlying coal smut above the Bluejacket sandstone and below the Weir-Pittsburg coal are tentatively correlated with the Seville limestone and the Bluejacket coal. These beds probably are lacking in the Cabaniss outcrop area farther south and west in southeastern Kansas, and accordingly the base of the underclay beneath the Weir-Pittsburg coal is regarded as the base of the formation there. The Weir formation, therefore, includes only the Weir-Pittsburg coal and its underclay. The thickness of the formation averages about 12 feet at outcrops in Cherokee and Crawford counties. The formation has not been observed in eastern Labette County, but is seemingly present at depth in western Labette County.

Underclay--The underclay of the Weir-Pittsburg coal is exceptionally thick in western Missouri and in Crawford and Cherokee counties, Kansas. It is characteristically light gray, somewhat silty, and contains fossil root impressions throughout. This clay is used in the manufacture of buff-burning brick by the United Brick and Tile Company at Weir City in northern Cherokee County. The clay is 5 to 7 feet thick at Weir City and about the same at Pittsburg.

Weir-Pittsburg coal--The Weir-Pittsburg (Haworth and Crane, 1898, p. 25-26) is the thickest coal in the southeastern Kansas region and has been most important commercially. The bed characteristically includes a thin clay parting 4 to 6 inches above the base. Over most of the area in Cherokee County and southern Crawford County where it has been mined, this coal is underlain by an uneven, plastic, dark-gray clay containing abundant fossil plant impressions and coaly material, and showing profuse slickensides. This type of clay, almost universally called "blackjack" by miners in the region, formed the floor of most of the mines operating on this bed in the area. The clay is not known at outcrops in eastern Crawford County, but it is exposed in southern Crawford County and northern Cherokee County and has been logged in coal prospect drilling in these areas. The plasticity of the "blackjack", according to Crane (in Haworth and Crane, 1898, p. 156-180), has been a source of considerable difficulty in underground mining because the clay absorbed much of the shock of blasts.

A thin coal bed is recorded beneath the "blackjack" in logs of some holes in Cherokee and Crawford counties, and it is found exposed in the clay pit of the United Brick and Tile Company at the southeastern edge of Weir City, in northern Cherokee County. This bed is logged in few of the drill-holes that penetrate the succession, however, and so its areal extent is unknown. In the single exposure seen it is only 3 to 4 inches thick.

The Weir-Pittsburg coal is locally impure in the upper and lower parts, and large amounts of fusain are common. Fusain in the coal commonly is completely filled or replaced by iron sulfide and presents a problem in coal preparation. In one area (see Tebo coal) the Weir-Pittsburg and Tebo coals are in contact.

Of importance in the mining of this bed are features called horsebacks. These are clay masses and ridges that have been displaced upwards through the coal. If numerous, they are especially detrimental in underground mining, but offer somewhat less difficulty in surface mining. These structures seemingly result from plastic flowage of the "blackjack" and underlying clay along planes and areas of weakness in the overlying coal. They are described in detail by Crane (in Haworth and Crane, 1898, p. 167-213).

The Weir-Pittsburg coal bed, excluding the "blackjack" and lower coal bed, averages about 38 inches in thickness in the Cherokee-Crawford County area. The lower coal, where present, is about 4 inches thick, and probably never has been mined by itself or in conjunction with the main bed above. The Weir-Pittsburg bed has been mined underground and by very extensive stripping in Cherokee and Crawford counties, as described by Abernathy (1944). The Weir-Pittsburg coal is not known to be present in the outcrop area in eastern Labette County, but has been strip-mined west of Welch, Craig County, Oklahoma. Numerous logs of prospect holes in western Labette County indicate that the bed is present at depth there, and that its maximum thickness is about 5 feet. The Weir-Pittsburg bed has been mined extensively also in western Barton County, Missouri, both by underground and surface methods.

The thin lower coal described above, although generally regarded as a part of the Weir-Pittsburg, may represent a portion of an additional formation, not heretofore recognized in southeastern Kansas. Lack of information concerning this coal precludes more than mention of its occurrence. It is possible that the "blackjack" layer described above and the thin clay parting within the main mass of the coal simply represent interruptions during a period of coal formation. The presence of locally abundant fusain may indicate periods of partial oxidation of coal-forming materials. The clay partings may consist of residue that results from a relatively long period of almost complete oxidation of coal-forming materials, plus introduced silt and clay. If this is true, the complete succession would be classed properly as the Weir-Pittsburg coal bed.

Other names applied to the Weir-Pittsburg coal in Kansas include: "Weir-Pittsburg lower", "Cherokee", "4-foot", and "Big Lower."

Tebo Formation

Definition and subdivisions--The Tebo formation (Searight and others, 1953) includes beds from the top of the Weir-Pittsburg coal extending upward to the top of the Tebo coal (Marbut, 1898, p. 123). The formation is well exposed in many strip mines in eastern Crawford County, Kansas, and in western Barton County, Missouri, for the Weir-Pittsburg coal has been strip-mined extensively in that area. The upper part of the succession is not known to be exposed in south-central Crawford County. In northwestern Cherokee County (NW sec. 25, T. 32 S., R. 22 E., and NE sec. 30, T. 32 S., R. 23 E.), the interval between the Weir-Pittsburg and Tebo coal beds decreases to zero and the two coal beds are in contact (Pl. 4B). In these localities, the composite Weir-Pittsburg-Tebo coal has been mined, but the coal, although 30 to 40 inches thick, is poor in quality and much of the upper part (Tebo) has been discarded. The irregular contact between the two coals is locally marked by a clay parting. The limestone bed (Tiawah) that normally lies above the Tebo coal is present in both localities. Study of spores from this locality by Mart P. Schemel, then with the Missouri Geological Survey, indicates that both the Weir-Pittsburg and Tebo coal beds are present. The results of Schemel's work corroborate earlier identification based upon field relations.

Thickness of the Tebo formation ranges from a few inches (including principally the Tebo coal bed) to about 26 feet in southeastern Kansas. It is 20 to 26 feet except in the area of the abrupt thinning described above.

In southeastern Kansas, the following divisions of the formation are recognized: dark- to light-gray silty to sandy shale at the base, impure limestone, underclay, and the Tebo coal bed at the top.

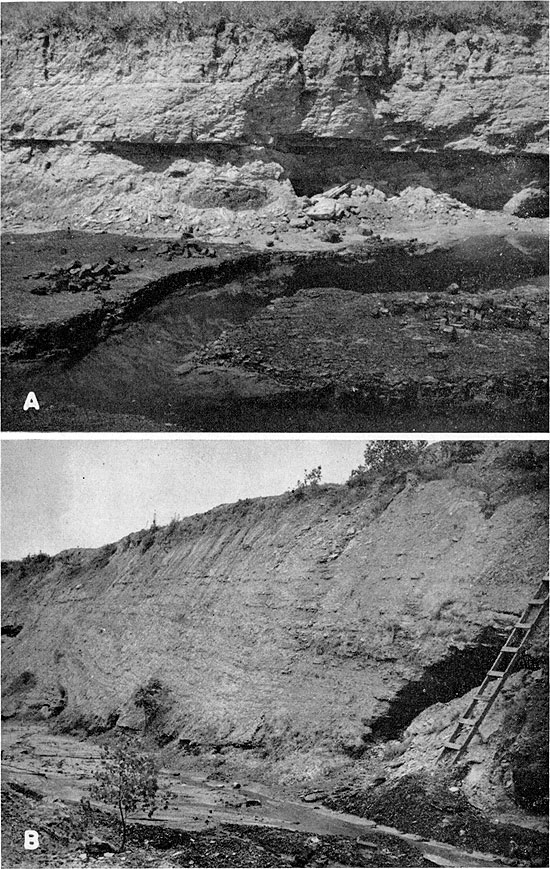

Shale--The lowermost division of the Tebo formation constitutes the major portion of the succession, and consists principally of gray silty shale. It is locally dark gray at the base. This unit is commonly sandy or silty, particularly in the upper part. In the large area of Weir-Pittsburg stripping in eastern Crawford County, Kansas, and in western Barton County, Missouri, the lower division ranges from clay shale ("soapstone") to sandy or silty shale; farther south and west, in southern Crawford County and northern Cherokee County, both outcrop descriptions and logs of coal prospect drilling indicate that this part of the formation consists chiefly of micaceous sandy or silty shale (Pl. 5A) and some interbedded fine-grained sandstone. Small isolated clay-ironstone concretions are common in this unit. Dark shale as much as 6 feet thick is present at the base at Weir City, in northern Cherokee County. Dark shale in the lower part of the division at other localities in northern Cherokee County is in general lenticular and has a maximum thickness of about 2 feet. No fossils were observed in the dark basal shale.

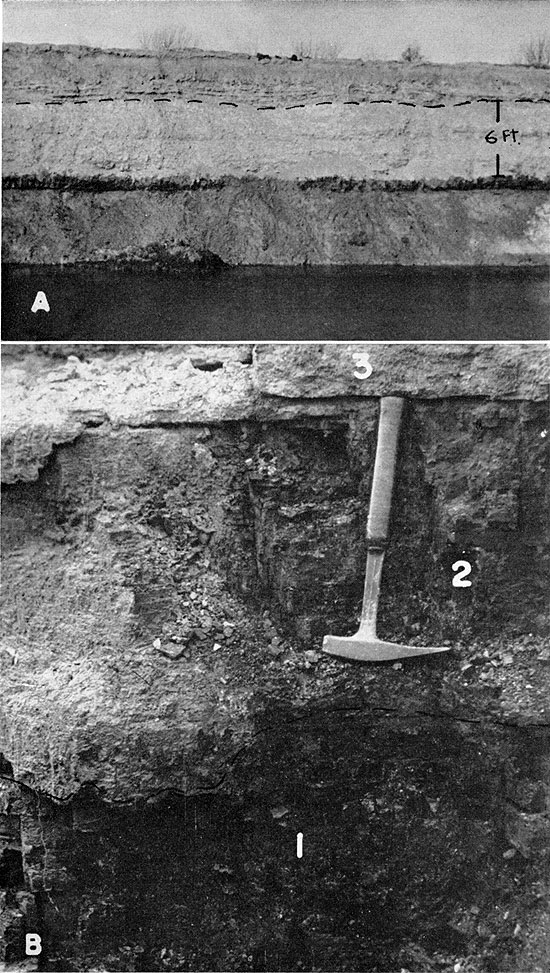

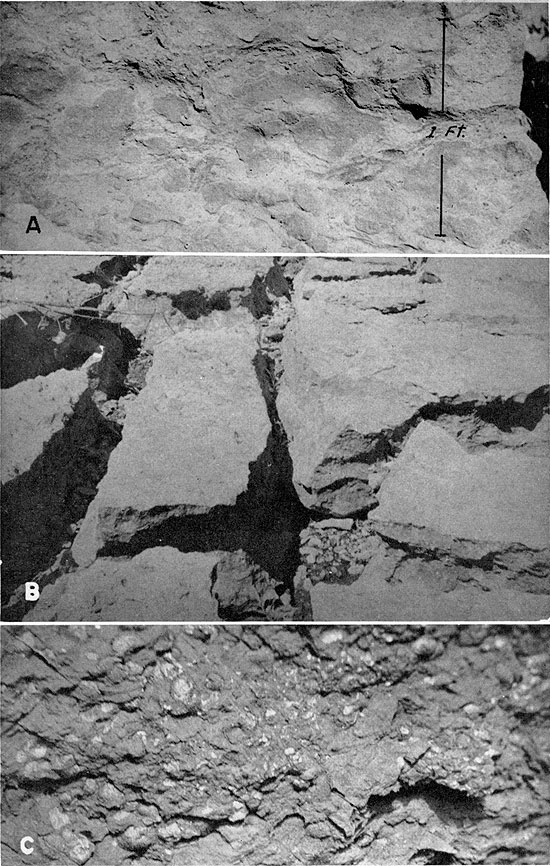

Plate 5--A. Weir-Pittsburg coal and overlying shale and thin-bedded sandstone of Tebo formation, NE NE sec. 13, T. 31 S., R. 24 E., Crawford County. B. Weir-Pittsburg coal and overlying thin-bedded sandy shale of Tebo formation, NE NE sec. 24, T. 32 S., R. 24 E., Cherokee County. Note inclination of bedding planes of shale relative to coal.

In several exposures of the lower shale, lamination is very slightly inclined to the plane of the underlying Weir-Pittsburg coal (Pl. 5B). This relationship of shale to underlying coal is, as far as is known, peculiar to this formation in the pre-Marmaton Pennsylvanian of southeastern Kansas. It is regarded as indicating some type of deltaic environment of deposition of the shale and sandy shale. In exposures where this feature was noted the inclination of the laminae was northerly. At an outcrop illustrated by Pierce and Courtier (1937, pl. 2B) purporting to show this relationship, the distinct unconformity shown is regarded by me as related to local structure and hence different from the generally barely perceptible inclination noted above.

The thickness of the shale forming the lower unit of the Tebo formation ranges from a featheredge, bordering the area where the Weir-Pittsburg and Tebo coal beds are in contact, to about 25 feet. Over most of the area, thickness of the shale ranges from 15 to 20 feet.

Underlimestone--Impure nodular to massive limestone above the lower shale and below the underclay of the Tebo coal is present in exposures in eastern Crawford County, Kansas, and in western Barton County, Missouri, but has not been noted elsewhere. Limestone at this position grades laterally from a thin zone of nodules in a clayey matrix to a single massive bed having a maximum thickness of about 10 inches. The rock is mottled light and dark gray. The darker portions are irregular fragments of very fine grained limestone scattered at random in the slightly coarser grained and lighter colored matrix. Insoluble material in the rock is about 10 percent of the total, and consists chiefly of fine silt and clay. Thin veinlets of calcite are common. No material of organic nature could be recognized in acetate peel sections of the rock.

Underclay--The underclay of the Tebo coal is silty and gray and contains root impressions. Its average thickness is about 3 feet.

Tebo coal--The Tebo coal of Henry County, Missouri (Marbut, 1898, p. 123) is a correlative of the "Pilot" coal (Pierce and Courtier, 1937, p. 68-69) of southeastern Kansas, and the term Tebo is adopted in this report. The coal is not of minable thickness in southeastern Kansas except where it is in contact with the Weir-Pittsburg coal (see discussion in definition and subdivisions), and has been mined with it. The Tebo coal is of minable thickness in some areas in Missouri, but seemingly has not been mined in northern Oklahoma. Exposures and logs of coal prospect drilling indicate that the average thickness of this coal bed in Cherokee and Crawford counties is about 6 inches. It has not been observed in the outcrop area in eastern Labette County, Kansas, but is present to the south in Craig County, Oklahoma, and seems to be present at depth in western Labette County.

Popular names applied to this coal are "Pilot" and "Sun bed". Both are miner's terms.

Scammon Formation

Definition and subdivisions--The Scammon formation (Searight and others, 1953) includes those beds next above the Tebo coal and extends to the top of the Scammon coal. At the type locality of the Scammon coal at exposures along Cherry Creek, northwest of Scammon, in Cherokee County (Abernathy, 1936, p. 83-84; 1938, p. 195) only underclay and coal, overlain by about 3 feet of fossiliferous dark fissile shale and thin limestone beds, are exposed. The fauna of these beds is similar to that present above the Tebo coal, and it is possible that the type Scammon is actually Tebo. Because the name Scammon has had continued usage, and because its nomenclator did specify its stratigraphic position as being between the "Pilot" (Tebo) and Mineral coal beds, the term has been adopted in recent usage (Searight and others, 1953). The complete succession included in this formation is exposed at only one Kansas locality (strip-pit highwall in SE NE sec. 24, T. 28 S., R. 25 E., Crawford County). As the Scammon coal bed is too thin to be mined and lies about 23 feet below the Mineral coal and 55 to 60 feet above the next lower minable coal, the complete succession is unlikely to be exposed in strip-mining operations. The lower part of the formation is exposed in many strip mines operating on the Weir-Pittsburg coal bed. Data from logs of coal prospect drilling provide most of the information on thickness and general character of this formation in the greater part of the area, where the complete succession is not exposed.

The Scammon formation, as defined, may eventually be divided into two formations, as an unnamed coal bed is present about midway between the Tebo and Scammon coals. The locally very prominent Chelsea sandstone occurs a few feet above this coal, and a generally less well developed sandstone bed is present below it. The coal bed or coal horizon that might properly mark the base of an upper unnamed formation has been identified in strip pits in the area along the Kansas-Missouri state line north of Mulberry, in eastern Crawford County, Kansas, and in western Barton and Vernon counties, Missouri. A well-defined coal bed at this position has been observed only in a single exposure in southwestern Vernon County, Missouri (Personal communication, W. V. Searight, April 1, 1954). In other outcrop areas in western Missouri and in southeastern Kansas the Chelsea sandstone rests upon an erosion surface extending down through lower beds and locally through the Tiawah limestone and underlying Tebo coal. The fine-grained sandstone below the unnamed coal is thus cut out in most places, and the Chelsea sandstone occupies its position. Because of the very restricted area in which this coal horizon is recognized, the complete succession from the Tebo to the top of the Scammon coal is herein regarded as constituting the Scammon formation.

The Scammon formation has not been recognized in the Cabaniss outcrop area in eastern Labette County. This succession should crop out in the area south of Chetopa, but a combination of structural conditions and poor exposures conceal relationships of beds younger than the Bluejacket sandstone but older than the Mineral coal. On Timbered Hill, east of Bluejacket, in Craig County, Oklahoma, the Chelsea sandstone is 10 to 20 feet thick, is conglomeratic, and rests upon an erosion surface extending down at least to the Weir-Pittsburg coal. The magnitude of the unconformity at that and other localities in northern Oklahoma is seemingly controlled by folding or faulting or both. It is suggested that similar conditions are associated with the seeming absence of part of the Cabaniss succession south of Chetopa. Sandstone, believed to be Bluejacket, south of Chetopa along Neosho River is of unusual thickness, compared to that of the outcrop area farther north and east in Kansas and in northern Oklahoma. It may be a composite sandstone, comprising both the Chelsea and the Bluejacket.

The thickness of the Scammon formation ranges from 28 to 32 feet in eastern Crawford County, and from 35 to 45 feet in central and southern Crawford County and northern Cherokee County.

In southeastern Kansas the following divisions of the Scammon formation are recognized: dark-gray to black fissile shale at the base, including a single limestone bed (Tiawah); fine-grained sandstone and siltstone; medium- to dark-gray shale; sandstone (Chelsea); underclay; and the Scammon coal bed at the top.

Lower dark shale and limestone--The succession of closely related beds forming the lower division of the Scammon formation characteristically includes 1 to 2 feet of black, fissile shale directly above the Tebo coal, overlain by impure pyritic limestone averaging about 4 inches in thickness, which is in turn overlain by 5 to 7 feet of dark-gray to black fissile shale containing several persistent clay-ironstone beds. This succession is particularly characteristic of the exposures in eastern Crawford County. Exposures in Cherokee County show a somewhat thinner succession, in which the limestone is the principal bed. There are small phosphatic concretions in the black shale over the coal in some exposures.

The limestone bed in the succession is the Tiawah (Lowman, 1932, p. 2). It is correlated with the Seahorne limestone of Illinois (Wanless, 1931a, p. 179-193), and Iowa (Weller, Wanless, Cline, and Stookey, 1942, p. 1588), and with the limestone member of the Loutre formation (McQueen, 1943, p. 71-78) of northern Missouri. The name Tiawah for this bed has had widest usage in this area and was adopted at the Nevada conference (Searight and others, 1953). The Tiawah in eastern Crawford County is typically extremely dense, tough, and pyritic, forming a single resistant ledge. The rock weathers to a soft hematitic and limonitic mass. In exposures in Cherokee County this bed is somewhat shaly and generally carbonaceous, and averages about 4 inches in thickness. In the type area in Rogers County, Oklahoma, this bed reaches a thickness of about 4 feet, and closely resembles the Verdigris limestone.

The Tiawah limestone contains abundant fossils at most exposures. The fauna is chiefly characterized by very abundant gastropods, including Naticopsis altonensis and Trachydomia oweni, which are regarded as distinctive of this bed. The brachiopods Mesolobus lioderma, Chonetina flemingi, and Dictyoclostus americanus are also very common in it. In addition to the invertebrate fauna, the Tiawah in many places in Kansas and in Missouri contains a large percentage of tabular masses of algal material, which contributes considerably to the calcium carbonate content of the rock. Figure 8 illustrates the tabular rock structure formed of algal masses. Johnson (1956) has studied material from this and other Pennsylvanian beds and has assigned the algae to the genus Archaeolithophyllum. Fossils in the black shale beds below and above the Tiawah consist principally of orbiculoids, but include pelecypods and conodonts.

Figure 8--Algal laminae in Tiawah limestone, Cherokee County.

The lower member of the Scammon formation is present in Crawford and Cherokee counties, but seemingly is absent in eastern Labette County.

Sandstone above the lower shale and limestone--In outcrops in the area along the Kansas-Missouri state line north of Mulberry, in eastern Crawford County, Kansas, thinly laminated sandstone and siltstone (Pl. 6A) are present above the lower shale and limestone and below the unnamed coal horizon that lies between the Tebo and Scammon coals. This unit consists of thin, ripple-marked, interlaminated beds of fine-grained micaceous sandstone and siltstone, and is 6 to 8 feet thick. The rock contains structures attributed to contemporaneous deformation, and in some places is characterized by abundant worm trails. In other areas where this part of the Scammon succession is exposed, the Chelsea sandstone lies on an erosion surface extending below this bed. Logs of coal prospect drilling in Cherokee and Crawford counties indicate that the beds constituting the Scammon formation consist chiefly of sandstone and sandy shale above the dark shale and limestone at the base. The lower sandstone could not be identified with certainty in the available logs, and the general presence of the Chelsea sandstone is inferred. In an exposure in a strip pit highwall in the SW sec. 18, T. 33 N., R. 33 W., Barton County, Missouri, the uppermost part of the lower sandstone contains abundant carbonized plant material, and is soft and ferruginous. At all Kansas exposures in which it can be differentiated, the lower sandstone is bounded at the top by a very sharp lithologic break (Pl. 6A). It is overlain by dark shale or by clay-ironstone, which is overlain by dark shale.

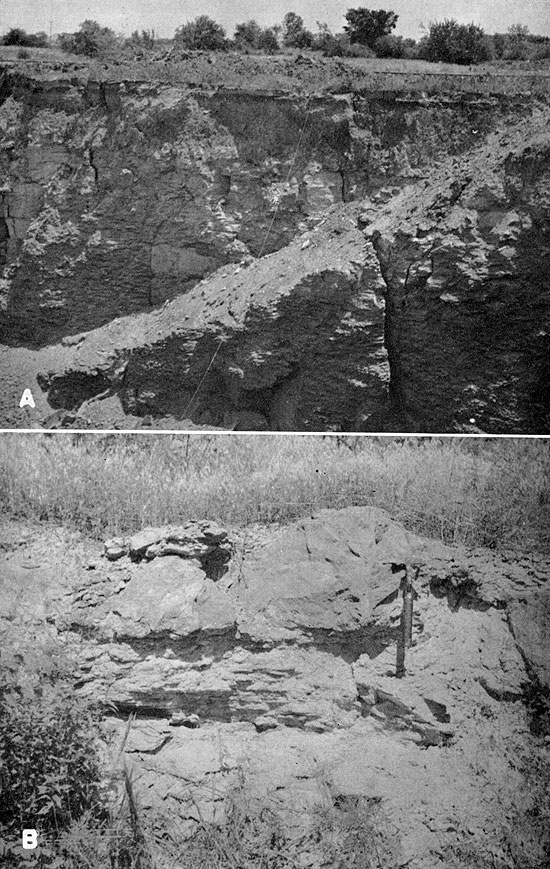

Plate 6--A. Sandstone above Tebo coal and below unnamed coal horizon (chisel point), SE NW sec. 24, T. 28 S., R. 25 E., Crawford County. B. Scammon coal (1) and overlying limestone (2), SE NW sec. 24, T. 28 S., R. 25 E., Crawford County. Note underlimestone at base of underclay.

Shale above unnamed coal horizon and below Chelsea sandstone--Dark- to light-gray clay shale is present above the coal horizon that lies between the Tebo and Scammon coal beds in the area adjacent to the Kansas-Missouri state line north of Mulberry, Kansas. This shale unit, dark gray to black at the base, rests upon the thinly laminated sandstone below or upon a thin bed of clay-ironstone, which in turn rests on sandstone. No fossils were observed in this shale. Its thickness is uneven, as the overlying Chelsea sandstone rests unconformably upon it. The maximum thickness in exposures is about 5 feet; the bed is not differentiated in logs. It is probable that its distribution is very local in southeastern Kansas, and also in western Missouri, because of pre-Chelsea erosion

Chelsea sandstone--The Chelsea sandstone (Ohern, 1914; Cooper, 1927, p. 161; Oakes, 1944, p. 10) of Oklahoma occurs above the Tiawah limestone, locally cutting through it and resting on lower beds. It is locally conglomeratic, particularly in the lower part. Conglomeratic material in the Chelsea in northern Oklahoma consists almost entirely of fragments of clay-ironstone concretions, phosphatic nodules, and detrital wood and coal, seemingly all of local origin. In Kansas and in western Missouri, sandstone having the same regional habitude occurs at the same stratigraphic position, hence the usage of the term is extended into that area.

The Chelsea sandstone is present in exposures in strip mines in eastern Crawford County, Kansas, and in western Barton County, Missouri. It also forms the cap of several outliers in the latter area. Logs of coal prospect drilling in Cherokee and Crawford counties indicate that the Chelsea constitutes most of the rock included within the Scammon formation over most of the two-county area. A maximum thickness of almost 30 feet of Chelsea sandstone is present in the highwall of an abandoned strip mine in the NW sec. 20, T. 32 N., R. 33 W., Barton County, Missouri. At that locality the Chelsea rests on an erosion surface extending below the Tebo coal, and the basal part is conglomeratic (Pl. 7A).

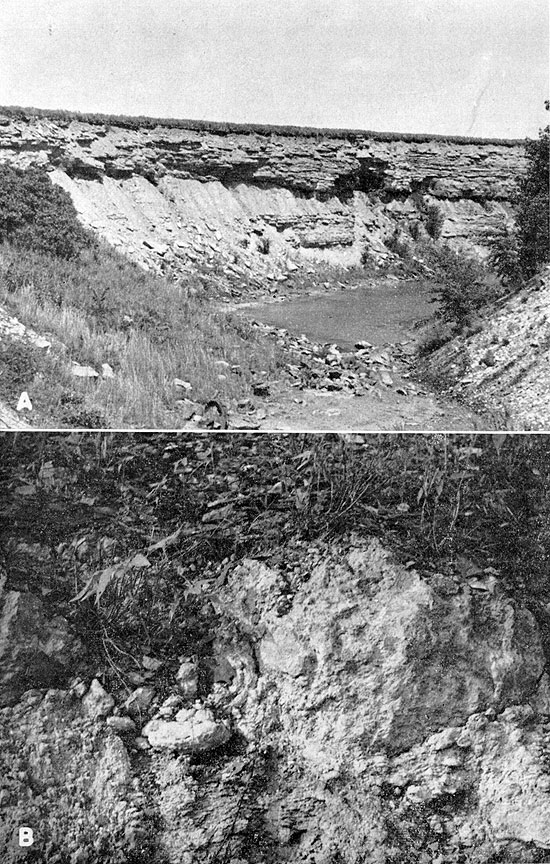

Plate 7--A. Chelsea sandstone, NW sec. 20, T. 32 N., R. 33 W., Barton County, Missouri. Weir-Pittsburg coal was mined here. Tebo coal and Tiawah limestone are cut out. B. Breezy Hill limestone in road cut east of Oswego, SE SW sec. 15, T. 33 S., R. 21 E., Labette County. Black shale above is Excello.

The Chelsea is typically a gray to brown, very fine grained, micaceous, finely to coarsely cross-bedded sandstone. It is extremely friable. Where conglomeratic this bed includes materials of local origin.

At a single exposure (abandoned strip pit in SE NW sec. 24, T. 28 S., R. 25 E., Crawford County, Kansas), sandstone regarded as Chelsea is present beneath the underclay of the Scammon coal and seems to grade laterally to impure limestone. The Chelsea has a maximum thickness of about 5 feet in this exposure, which is in an area where the Scammon formation is relatively thin, and the shale below the Chelsea and above the unnamed coal attains its maximum known thickness. The impure limestone and the Chelsea sandstone are regarded as near equivalents in age.

The Chelsea sandstone has not been identified positively in southeastern Labette County (see discussion under definition and subdivisions).

Underclay--At the single locality where the complete Scammon succession is exposed, the underclay of the Scammon coal is light gray, plastic, and iron-stained. Its thickness is about 3 feet at this exposure.

Scammon coal--The Scammon coal (Abernathy, 1936, p. 83-84; 1938, p. 195) ranges from 4 to 9 inches in thickness in exposures and in available logs. It is commonly recorded in logs as being about 8 inches thick. This coal is not of minable thickness in southeastern Kansas. It has not been identified in Labette County, but is consistently logged in Cherokee and Crawford counties. The coal has not been observed in outcrop or recorded in logs in western Missouri (Personal communication, W. V. Searight, April 22, 1954), and has not been identified in northern Oklahoma. Plate 6B is a photograph of this coal and associated beds at a locality north of Mulberry, Crawford County, Kansas.

Mineral Formation

Definition and subdivisions--The Mineral formation (Searight and others, 1953) includes beds above the Scammon coal and extends upward to the top of the Mineral coal (Pierce and Courtier, 1937, p. 69-70). At the present time, the coal bed (Mineral) included in this formation is the most important strippable coal in the region. Only one exposure is known where the relations of the succession included in the Mineral formation are perfectly clear. The sequence between the Mineral and the next lower minable coal (Weir-Pittsburg) is too great for the two beds to be mined in tandem operation at the present time; thus artificial exposures of the succession are extremely scarce. Most strip mines operating on the Mineral bed expose only the coal and overlying beds, plus the upper part of the associated underclay. Accordingly, logs of coal prospect drilling provided most of the available information relevant to these beds in Kansas. In the single locality (strip-pit highwall in SE NW sec. 24, T. 28 S., R. 25 E., Crawford County) where the succession included in the Mineral formation is exposed, the following divisions are differentiated: limestone (cap-rock of the Scammon coal), dark shale, underlimestone, underclay, and the Mineral coal bed at the top. The thickness of the Mineral formation in Crawford and Cherokee counties averages about 23 feet. It is somewhat less in northeastern Crawford County, where measurements of less than 15 feet are common. The divisions of the Mineral formation are described in ascending order both from outcrop and from subsurface information.

Lower limestone bed--The lower limestone bed is recorded from only one exposure (see above). It is almost certainly more extensive in southeastern Kansas, but is not recorded in logs of coal prospect holes, which in the absence of outcrops represent the most reliable source of information. It is probable that impure limestone is widespread at the base of the formation but has not been logged as such because of the generally dark and shaly nature of limestone at this position.

The limestone identified by Abernathy in the vicinity of the type section of the Scammon coal as the cap-rock of that coal is not regarded as a part of the Mineral formation (see discussion of Scammon formation).

At the only exposure where there is no question as to the relationship of the beds involved, the lower limestone present in the Mineral formation is dark gray to black, and forms a prominent ledge ranging from 2 to 14 inches in thickness (Pl. 6B). Abundant fossils in this bed include: Dictyoclostus americanus, Neospirifer cameratus, Mesolobus sp., Chonetina flemingi var. crassiradiatus, and fusulines.

Dark shale--In the exposure in the SE NW sec. 24, T. 28 S., R. 25 E., in Crawford County, dark, thinly laminated shale is present above the lower limestone and below impure limestone identified as underlimestone. The thickness of the shale at that locality is about 10 feet. Dark-gray to black shale is recorded between the Mineral coal bed and the Scammon coal bed in nearly all of the available logs of coal prospect holes in Cherokee and Crawford counties, and in most logs it makes up nearly all of the section involved. Thickness of this shale unit of the formation increases to an average between 18 and 20 feet in the area south and west of Pittsburg. The thickness of the shale is fairly uniform in Cherokee and Crawford counties, except in the northern part of T. 32 S., R. 23 E., Cherokee County, where it is much less regular, ranging from 14 to 35 feet. The succession between the two coals is logged as containing sandstone and sandy shale only in T. 30 S., R. 24 E., Crawford County, one of ten townships in which reliable subsurface data are available.

Underlimestone and sandstone--At the only known exposure of the complete Mineral succession (see above), deeply weathered, argillaceous limestone and iron-stained, plastic clay are present below the Mineral coal and above the dark shale described above. The thickness of the underlimestone at this locality is about 2 1/2 feet.

Lateral extent of underlimestone in this formation cannot be ascertained from well logs, but the bed is probably widespread, in view of the seemingly local distribution of sandstone (see above). Regionally, it is normal for coal beds above the Weir-Pittsburg coal to have either limestone or sandstone below their respective underclays, and the geologist's tendency is to expect one if the other is absent.

Underclay--Information from logs of coal prospect holes in Cherokee and Crawford counties indicates that the underclay of the Mineral coal ranges in thickness from 1 to 3 feet.

Mineral coal--The Mineral coal (Pierce and Courtier, 1937, p. 69-70) is present in minable thickness along most of the line of outcrop in southeastern Kansas, and has been the most important strip-mined coal in the area. It is second in importance to the Weir-Pittsburg bed. It is 18 to 20 inches thick in most exposures in northeastern Crawford County, and ranges from a few inches to about 18 inches in thickness in southeastern Bourbon County. It is 18 to 24 inches thick in central and southern Crawford County and in northwestern Cherokee County, and its maximum logged thickness is 32 inches in T. 31 S., R. 23 E., Cherokee County. In Labette County the Mineral is somewhat thinner, averaging about 12 inches.

The Mineral coal lies 60 to 80 feet above the Weir-Pittsburg coal in Crawford and Cherokee counties. An interval of 70 to 80 feet is common; lesser intervals separate these beds in areas in Cherokee County where the Weir-Pittsburg and Tebo coals converge (see Tebo formation). The Mineral coal bed has been stripped along nearly all of the crop line in southeastern Kansas. Pierce and Courtier (1937, p. 71) reported that a few shafts had been opened on this bed in the vicinity of Mineral, in Cherokee County, but virtually all of the actual mining of this bed in southeastern Kansas has been strip mining.

The Mineral has also been mined extensively in western Missouri, and to a minor degree in northern Oklahoma. Other names of popular derivation that have been applied to this bed include: "Weir-Pittsburg upper", "Lightning Creek", "Baxter", "22-inch", and "Top vein".

Robinson Branch and Fleming Formations

Definition and subdivisions--The Robinson Branch formation (Searight and others, 1953) includes beds above the Mineral coal and extends upward to the top of the Robinson Branch coal. The Fleming formation (Searight and others, 1953) includes those beds above the Robinson Branch coal and extends to the top of the Fleming coal (Pierce and Courtier, 1937, p. 73).

These formations are described together in this report because the succession called Robinson Branch, although present in both Kansas and Missouri, is very local in its distribution. In the greater part of the area the underclay of the Fleming coal lies on marine shale associated with and lying above the Mineral coal bed; the Robinson Branch coal and overlying limestone and shale are absent. For practical purposes, therefore, the Fleming formation consists of beds above the Mineral coal, including the Fleming coal at the top.

From the facts already noted it is apparent that the succession between the Mineral and Fleming coal beds is erratic. The underclay associated with the Fleming coal is characteristically fairly thick and rests unconformably on the limestone and shale successions associated with the Mineral coal (most common relationship), on those associated with and lying above the Robinson Branch coal, or on the underclay of the Robinson Branch coal. This relationship probably accounts for the locally abnormal thickness of the Fleming underclay; in reality it is in places formed of two separate and unrelated beds of clay.

Robinson Branch Formation

This formation includes strata above the Mineral coal and extends to the top of the Robinson Branch coal, from which the formation is named, and which, in turn, is named for Robinson Branch, a stream in Vernon County, Missouri. The complete succession was formerly exposed in strip pits northeast of Walker, in the SW sec. 2, T. 36 N., R. 30 W., in Vernon County (Personal communication, W. V. Searight, April 22, 1954).

The Robinson Branch together with the Fleming succession is known to be completely developed in southeastern Kansas only in the southern part of T. 32 S., R. 22 E., in Cherokee County. Stratigraphic section 35 includes description of beds between the Mineral and Fleming coals in that locality. The succession is no longer exposed, having been covered by subsequent mining operations. No exposures of the completely developed Mineral-Fleming sequence other than that at the type locality in Missouri and in the locality described above are known to the writer in either Kansas or Missouri. The spotty distribution of these beds is interpreted as being due to preservation only in isolated structural depressions prior to the period of Fleming sedimentation. The Robinson Branch coal and associated beds above it have not been observed in reconnaissance in northern Oklahoma.

The Robinson Branch formation includes, from the base upward, limestone and calcareous shale (cap-rock of Mineral coal), dark shale, fine-grained sandstone, underclay, and the Robinson Branch coal. Of these the lower limestone and the overlying dark shale divisions are most persistent in the outcrop area in northern Oklahoma, Kansas, and Missouri.

Lower limestone and calcareous shale--In exposures in Cherokee and Crawford counties the lower part of the succession of beds classed as the Robinson Branch formation includes lenticular beds of massive coquinoidal limestone (cap-rock of Mineral coal) at the base, and fossiliferous calcareous shale above it or, in the absence of the limestone, directly over the Mineral coal bed. Lenticular limestone at this position is interpreted as having been formed as a biohermal accumulation of organic debris. In eastern Labette County, Kansas, and in Craig County, Oklahoma, limestone at this position forms an almost continuous bed, averaging about 18 inches in thickness. Small rough phosphatic concretions are present in association with this member in Cherokee and Crawford counties, but are much more common and characteristic of it in eastern Labette County, Kansas, and in Craig County, Oklahoma. Most such concretions have the small phosphatic brachiopod Orbiculoidea missouriensis as a nucleus. They persist regardless of the presence or absence of limestone.

Limestone at this position in Cherokee and Crawford counties ranges in thickness from a featheredge to about 3 feet. In Labette County and in Craig County, Oklahoma, where it is present as a persistent bed, its thickness ranges from about 1 foot to an observed maximum of 30 inches. Branson (1952, p. 191) applied the name Russell Creek to this limestone in Craig County, Oklahoma. Calcareous shale present above the limestone, or over the Mineral coal, in the absence of any limestone, ranges from a few inches to about 3 feet in thickness.

Fossils in the lower limestone and calcareous shale division of the Robinson Branch formation include abundant Dictyoclostus americanus, Neospirifer cameratus, Composita subtilita, and crinoidal material. Mesolobus euampygus and Marginifera muricatina are less abundant. Fusulina sp., Wedekindellina cf. euthesepta, and Fusulinella? are also common in the lower division, Fusulina predominating. Crinoid columnals found in these beds are in general larger than those found in other beds within the Krebs and Cabaniss subgroups in the region. In the larger columnals the axial canal is slightly off center in many of the specimens examined. Crinoid columnals of this size (1/2- to 3/4-inch diameter) and with this distinguishing earmark seem to be restricted to this zone.

Dark shale--Dark-gray to black shale, weathering dark to light gray, overlies the lower calcareous shale and limestone unit of the Robinson Branch formation in all exposures observed in the area of this report. The shale is thinly laminated, and in general breaks down rapidly upon weathering. Scattered fossils, principally the brachiopod Mesolobus decipiens, are present in the lower part of this unit. In most places this shale member is overlain by the underclay of the Fleming coal bed, the Robinson Branch coal and closely associated clays and shales being absent or indistinguishable. Locally, very fine grained sandstone or siltstone lies between the dark shale and overlying underclay units. The average thickness of the dark shale member of the formation in southeastern Kansas is about 8 feet.