Prev Page--Geography || Next Page--Sections, Johnson Co.

Stratigraphy

The oldest rocks exposed in the Johnson and Miami County area belong to the division of rocks called the Pennsylvanian system, so named because of their great development in Pennsylvania. These rocks consist in eastern Kansas of interbedded layers of shale, limestone, and sandstone. Most of the formations were deposited in the sea, a conclusion well supported by the occurrence in them of abundant shells of marine animals.

Other deposits are glacial gravels and clay that were brought to the valley of Kansas river by a vast ice sheet, a continental glacier, that covered much of the upper part of the Mississippi Valley region during a part of the Pleistocene epoch. These gravels contain fragments of quartzite of the kind found as bedrock in southwestern Minnesota and adjacent parts of South Dakota and Iowa. Ice-transported boulders and pebbles of this rock are common in glacial deposits of Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska, and northeastern Kansas. Deposits of loess blown from the river flood plains along Missouri and Kansas rivers and redeposited on the uplands bordering the valleys occur in northern Johnson County. The loess of this area is connected in origin with the ice invasion and is composed in part of the finely ground rock dust brought from the northern area by the glacier. Younger deposits of recent age collectively make up the soil covering and flood-plain alluvium.

Pennsylvanian System

The thin beds of alternating shale, limestone, and sandstone that appear at the surface in eastern Kansas and adjacent parts of Missouri, Oklahoma, and Nebraska belong to the Pennsylvanian system. In much of the area of the Mid-Continent Coal Basin the rocks of Pennsylvanian age have generally been divided into two groups or series, the Des Moines series below and the Missouri series above. According to this classification of the strata, the Des Moines series is composed of the Cherokee and Marmaton groups, named in order from older to younger rocks. The Missouri beds, as defined in the past, include five groups, named in order upward, Kansas City, Lansing, Douglas, Shawnee, and Wabaunsee. Each of the groups contains a number of formations and many of these in turn are made up of smaller named units, called members.

The old classification of the Pennsylvanian rocks of the northern Mid-Continent region is unsuitable in several respects, and recent work has shown that it is based in many cases upon false premises. In order to formulate a more natural system of classification, one that is based upon modern knowledge of Mid-Continent stratigraphy, R. C. Moore has advanced a new classification of the Pennsylvanian system for the northern Mid-Continent region. [Moore, R. C., Guidebook, Sixth Annual Field Conference, Kansas Geol. Soc., 1932.]

Hinds and Greene have made known the occurrence of a major unconformity in the † Pleasanton formation, supposedly coincident with a widespread faunal break. [Hinds, Henry, and Greene, F. C., The stratigraphy of the Pennsylvanian series in Missouri: Missouri Bur. Geology and Mines, vol. 13, 2d ser., pp. 75-102, 1915. In accordance with a revised code of Rules of Stratigraphic Nomenclature recently formulated by a national committee of geologists, abandoned stratigraphic terms are designated by a dagger (†) preceding the term.] At this unconformity Moore proposes to place the lower limit of the Missouri series as redefined.

In their study of the Pennsylvanian rocks of Missouri, Hinds and Greene" also discovered a great channel sandstone lying between the Stanton and Oread formations in Platte county, Missouri, and the region about Leavenworth, Kan. [Hinds, Henry, and Greene, F. C., The stratigraphy of the Pennsylvanian series in Missouri: Missouri Bur. Geology and Mines, vol. 13, 2d ser., pp. 170-171, 1915.] This sandstone deposit was traced by J. M. Jewett and me across Wyandotte County. In the present study it was found that the sandstone, marking the base of the Stranger formation of this report, is continuous across Johnson and Franklin counties, and it has subsequently been traced into Oklahoma. In southeastern Kansas' sandstones of the Stranger formation produce a high escarpment that affords an abundance of good exposures. The formation extends almost continuously as a great sandstone sheet across Kansas, resting unconformably upon older rocks, in most places upon the clayey Weston shale, but in Leavenworth, Wyandotte, and northwestern Johnson counties lying in many localities on the upper member of the Stanton. In Leavenworth county the unconformity rises to the northward from the surface of the Stanton to a horizon above the Iatan limestone, showing conclusively that the Iatan was deposited before the widespread emergence. The stratigraphic interval which the unconformable contact overlaps amounts to more than seventy feet in the Leavenworth region. This unconformity has been selected by Moore as the upper limit of his Missouri series as redefined. In most of northeastern Kansas the upper boundary of the Missouri series coincides with the top of the Lansing group of older writers, but in northwestern Missouri and probably in southeastern Kansas -strata as young as the Iatan limestone lie below the unconformity. For the Pennsylvanian strata above the unconformity just described, Moore has proposed the term Virgil series.

It was discovered in the study of Johnson and Miami counties that certain miscorrelations have been made by previous geologists between the classic exposures at Kansas City and type localities in southeastern Kansas. My correlations were made by continuous tracing of outcrops, and were verified by Dr. R. C. Moore, state geologist. The evidence for the present correlations is presented under the descriptions of formations in the following pages. J. M. Jewett, who is engaged in a study of the Bronson group, has made certain observations in southeast Kansas which affect the nomenclature of some of the formations.

In a recent publication J. M. Jewett proposed to abandon the term Hertha on the basis that it is a synonym of Bethany Falls. [, Jewett, J. M., Some details of the stratigraphy of the Bronson group of the Kansas Pennsylvanian Kansas Acad. Sci., Trans., vol., 86, pp. 131-186, 1983.] At the same time he introduced a number of terms for what he considered to be several disconnected lenticular limestones of slightly different stratigraphic position. F. C. Greene, R. C. Moore, and I have concluded, from an examination of field evidence, that possibly some errors were made by Jewett. It appeared to us that the Hertha limestone of general usage in the Kansas City is in reality part of the type Hertha. The problem is too involved to discuss at length here, but the classification of the lower Bronson units given in the present report is correct for northeastern Kansas and northwestern Missouri.

Some of the changes in correlation that affect classification and nomenclature of the rocks in Johnson and Miami counties are summarized as follows. The "Drum" limestone of Kansas City does not occur south of Martin City, Jackson county, Missouri (except possibly very locally in Miami County), and is not the equivalent of the type Drum limestone. The Cement City limestone of the Kansas City region is continuous with part of the type Drum, and the name Cement City is retained for the lower member of the Drum formation. The Raytown limestone is the exact equivalent of the upper part of the Iola limestone. The so-called Iola limestone at Kansas City does not occur at Iola, but is a previously unnamed unit. The Farley limestone coalesces in Miami County with the "Iola" of the Kansas City area to form an indivisible unit which contains the so-called Lansing brachiopod Enteletes throughout. The Kansas City and Lansing groups of authors cannot be divided either faunally or lithologically over much of eastern Kansas. The original description of the Stanton limestone refers to the previously named Plattsburg. It is proposed here, however, to retain the terms Plattsburg and Stanton in their current usage, because by so doing there is a minimum of confusion. The unconformity that occurs in the part of the section lying between the Stanton and Oread formations is easily recognized throughout most of eastern Kansas. It marks the base of a more or less continuous sandstone sheet older than the Lawrence and younger than the type Iatan. The limestone at Lawrence which marks the lower boundary of the Lawrence shale is not the Iatan, because it is well above the unconformity. Moore has termed this limestone at the base of the Lawrence the Haskell limestone.

Moore has suggested that the beds above the Des Moines-Missouri unconformity to the top of the Pleasanton of authors constitue a natural stratigraphic unit consisting mostly of shale. [Moore, R. C., A reclassification of the Pennsylvanian system in the northern MidContinent region, Guidebook, Sixth Annual Field Conference, Kansas Geol, Soc., pp. 79-97, 1932.] This he terms the Bourbon formation. For the persistent limestones and shales above the Bourbon to the top of the Winterset he has revived Adams' term, "Bronson," employing it in the original sense as regards stratigraphic boundaries, but classing it as a group rather than a formation. The highly variable and dominantly shaly strata between the top of the Winterset and the base of the Plattsburg formation he calls the Kansas City group. It will be noted that this involves revision of both the lower and upper boundaries of the Kansas City beds as proposed by Hinds and Greene, but it is the view of a large number of Mid-Continent geologists that it is preferable to retain this familiar name in a revised sense rather than to drop it in favor of an entirely new term. The persistent limestone strata between the base of the Plattsburg and the top of the Stanton are termed by Moore the Lansing group.

| Generalized section of the Pennsylvanian rocks exposed in Johnson and Miami counties | Feet | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virgil series: | |||||

| Douglas group: | |||||

| Stranger formation: | |||||

| Sandstone, buff, soft, cross-bedded, erosion remnant | 40+ | ||||

| Unconformity | |||||

| Missouri series: | |||||

| Pedee group: | |||||

| Weston shale | 0-40 | ||||

| Lansing group: | |||||

| Stanton limestone: | |||||

| Little Kaw limestone member: | |||||

| Limestone, bluish-gray, blocky | 2± | ||||

| Victory Junction shale member: | |||||

| Shale below, and brown sandstone above | 3-14 | ||||

| Olathe limestone member: | |||||

| Limestone, bluish-gray, thin-bedded, wavy | 11-15 | ||||

| Eudora shale member: | |||||

| Shale, carbonaceous, black | 4-11 | ||||

| Captain Creek limestone member: | |||||

| Limestone, dark-gray, even-bedded | 4-10 | ||||

| Vilas shale: | |||||

| Shale, gray, arenaceous | 5-30 | ||||

| Plattsburg limestone: | |||||

| Spring Hill limestone member: | |||||

| Limestone, drab or buff, even-bedded | 10± | ||||

| Hickory Creek shale member: | |||||

| Shale, yellowish, nodular, locally with a carbonaceous layer | 1± | ||||

| Merriam limestone member: | |||||

| Limestone, gray, blocky, even-bedded | 3± | ||||

| Kansas City group: | |||||

| Bonner Springs shale: | |||||

| Shale, olive-green, argillaceous, maroon layer near top | 25± | ||||

| Wyandotte limestone: | |||||

| Farley limestone member: | |||||

| Limestone, light-gray, thin-bedded, wavy | 10± | ||||

| Island Creek shale member: | |||||

| Shale, gray, limy, absent in Miami County | 0-5 | ||||

| Argentine limestone member: | |||||

| Limestone, light-gray, thin-bedded, wavy | 25± | ||||

| Quindaro shale member: | |||||

| Shale, gray, argillaceous or limy | 3± | ||||

| Frisbie limestone member: | |||||

| Limestone, gray, even, blocky, in one layer | 2± | ||||

| Lane shale: | |||||

| Shale, gray or buff, argillaceous, sandy where thick | 16-105 | ||||

| Iola limestone: | |||||

| Raytown limestone member: | |||||

| Limestone, bluish-gray, even-bedded | 5-13 | ||||

| Muncie Creek shale member: | |||||

| Shale, carbonaceous where thick, argillaceous where thin, with spherical phosphatic concretions | 0.5-3 | ||||

| Paola limestone member: | |||||

| Limestone, bluish-gray, even, blocky | 1.5 | ||||

| Chanute shale: | |||||

| Shale, lower half argillaceous, upper half arenaceous (Cottage Grove sandstone), Thayer coal bed near the middle in southern Miami County | 8-38 | ||||

| Drum limestone: | |||||

| Cement City limestone member: | |||||

| Limestone, ferruginous, drab or brown, thick-bedded | 2-10 | ||||

| Quivira shale: | |||||

| Shale, black, carbonaceous, argillaceous above and below | 4-11 | ||||

| Westerville limestone: | |||||

| Limestone, drab, irregular, oolitic where thick | 0-20 | ||||

| Wea shale: | |||||

| Shale, argillaceous or calcareous, greenish or gray | 10-30 | ||||

| Block limestone: | |||||

| Limestone and calcareous buff shale, more shaly in Johnson County | 6± | ||||

| Fontana shale: | |||||

| Shale, gray or buff, argillaceous or calcareous | 5-25 | ||||

| Bronson group: | |||||

| Dennis limestone: | |||||

| Winterset limestone member: | |||||

| Limestone, gray, even, thin-bedded | 30 | ||||

| Stark shale member: | |||||

| Shale, black, carbonaceous below, argillaceous above | 4-7 | ||||

| Galesburg shale: | |||||

| Shale, buff, argillaceous or calcareous | 2-3 | ||||

| Swope limestone: | |||||

| Bethany Falls limestone member: | |||||

| Limestone, drab, massive, oolitic above | 13-27 | ||||

| Hushpuckney shale member: | |||||

| Shale, black, platy, with clay layer above and below | 5 | ||||

| Middle Creek limestone member: | |||||

| Limestone, bluish, even, blocky, two beds generally | 2 | ||||

| Ladore shale: | |||||

| Shale, buff, argillaceous, calcareous below | 7± | ||||

| Hertha limestone: | |||||

| Sniabar limestone member: | |||||

| Limestone, thick-bedded, ferruginous | 6 | ||||

| Bourbon formation: | |||||

| Shale, limy, ferruginous | 4± | ||||

| Limestone, nodular, ferruginous, very persistent | 2± | ||||

| Shale with channel sandstones, which possibly represent the Des Moines-Missouri boundary | 80± | ||||

Missouri Series

The term Marmaton was applied by Haworth to a thick limestone and shale succession lying between the Cherokee and the top of the Des Moines series as generally defined. Following the new usage proposed by Moore the upper limit of the Marmaton is lowered to the unconformity some scores of feet below the Kansas City group of current usage.

The Marmaton group is divided into several formations. These are, in ascending order: Fort Scott limestone, Labette shale, Pawnee limestone, Bandera shale, Altamont limestone, Nowata shale, Lenapah limestone, and Dudley shale. Because the Des Moines-Missouri boundary lies within and probably near the base of the Dudley shale it is advisable to abandon the term Dudley.

At one locality in Miami County, described below, there occurs just below the limestones of the Bronson group or lower "Kansas City" a local sandstone, seemingly a channel filling. It has not been determined as yet whether or not this channel marks the Des Moines-Missouri unconformity, but I am inclined to believe that it is stratigraphically higher than the base of the Missouri series. Thin fossiliferous limestones seen south of the Miami area and apparently occurring below the horizon 01 the channel sandstone alluded to above have not yielded Des Moines guide fossils. In the present discussion, therefore, it will be assumed that the lowest shale exposed in the area under consideration is the Bourbon shale, belonging in the Missouri series, and that the channel sandstone in southeastern Miami County does not mark the Des Moines-Missouri boundary.

The term Missouri was proposed by Keyes to include the "upper Coal Measures," that is, the higher part of the Pennsylvanian section as developed in northwestern Missouri. [Keyes, C. R., The geological formations of Iowa: Iowa Geol. Survey, vol. 1, pp. 85- 114, 1893.] Through usage the term has come to be applied to all of the Upper Pennsylvanian rocks in the northern Mid-Continent. Moore has redefined the term Missouri to apply to strata between the two extensive unconformities in the mid portion of the Mid-Continent Pennsylvanian, namely that above the Marmaton and the break shortly above the Stanton limestone.

The term Pottawatomie, from Pottawatomie creek in eastern Kansas, was applied by Haworth to strata included in Moore's Missouri series. [Haworth, E., Univ. Geol. Survey of Kansas, vol. 3, p. 94, 1898.] The term Pottawatomie, however, in the original sense does not apply to a natural unit, and the section along Pottawatomie creek is neither a desirable one for a type section nor does it include all of the strata of Haworth's Pottawatomie formation. Moore has deemed it more desirable to retain the widely used name Missouri than to revive Haworth's little-used term.

Hinds proposed to divide the old Pottawatomie formation into two divisions, the Kansas City and Lansing. [Hinds, Henry, Coal deposits of Missouri: Missouri Bur. Geology and Mines, vol. 2, 2d ser., p. 7, 1912.] This course was seemingly substantiated by both lithologic and faunal evidence and the classification has come into general usage. It is shown below, however, that the Kansas City division over great areas cannot be separated from the Lansing, either lithologically or faunally.

It is partly upon evidence presented in the following pages that Moore proposes to divide the redefined Missouri series into five groups, called Bourbon, Bronson, Kansas City, Lansing, and at the top Pedee. Kansas City and Lansing have been previously employed in a somewhat different sense.

Bourbon Formation

For the beds, consisting chiefly of shale in most places, between the unconformity at the base of the Missouri series and the base of the Hertha limestone, Moore proposes the term Bourbon, from a county in eastern Kansas. [Moore, R. C., Op. cit., p. 90.] As explained under the discussion of the Missouri series, the thick shale around La Cygne and in southeastern Miami County belongs largely or entirely to the Bourbon formation.

Lithologic character and thickness. In Miami County the lower part of the Bourbon is not shown, being below drainage level. A channel sandstone occurs in the upper part of the formation near the middle of the south edge of section 9, T. 19 S., R. 25 E. The deposit consists of soft cross-bedded sandstone having an estimated thickness of possibly fifty feet or more and a breadth at the outcrop of about a quarter of a mile. At other places in southeastern Miami County and at La Cygne, in Linn County, there is at the same horizon buff arenaceous shale and thin beds of sandstone. The shale succeeding the channel deposit in Miami County is generally arenaceous with intercalated layers of clay. It is about thirty feet or so thick.

The base of the Bourbon is not exposed in the vicinity of Miami County, so it is impossible to obtain the exact thickness from surface data. There is, however, about ninety feet of the formation exposed along the tributaries of Marais des Cygnes river in the southeastern part of the county. Near the top of the Bourbon formation there is a thin bed of nodular, ferruginous tan limestone, one or two feet thick, bearing, at least locally, specimens of a large Bellerophon, as does the overlying Sniabar. This limestone is the one called Critizer by Jewett. [Jewett, J. M., Kansas Acad. Sci., Trans., vol. 36, p. 134, 1933.] The term Critizer possibly cannot rightly be applied to this limestone because it seemed to F. C. Greene, R. C. Moore, and me that the limestone near Critizer in Linn County is another one. The upper shale of the Bourbon in Miami County consists of four feet or less of nodular greenish clay.

Since the Bethany Falls limestone is the lowest rock exposed in Johnson County, the Bourbon does not crop out within the limits of that county.

Detailed sections. Sections including part of the Bourbon formation are given under numbers 125, 158, and 159 at the end of the report.

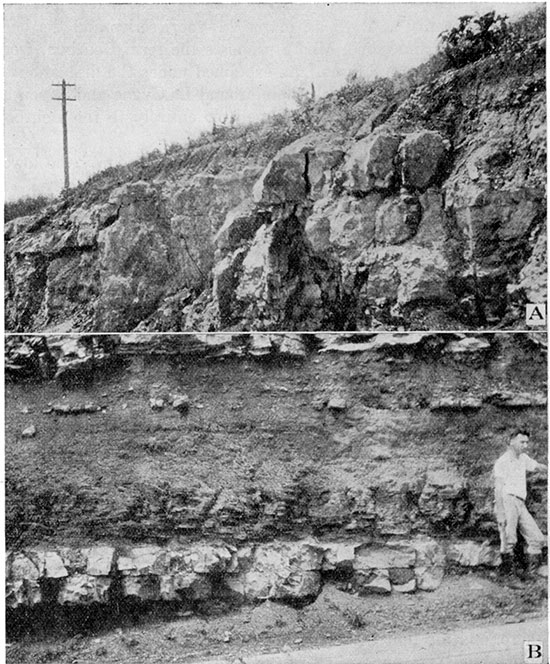

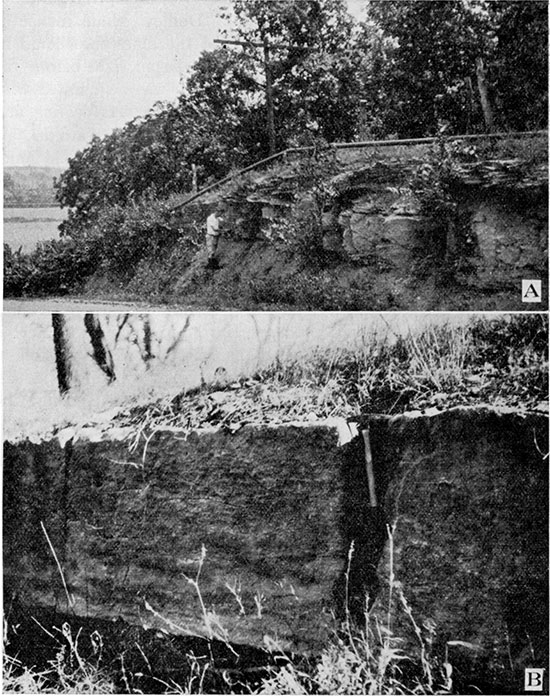

Plate III--Exposures of the Swope formation, SE cor. sec. 36, T. 19 S., R. 24 E., Linn County. A--Bethany Falls limestone. B--Middle Creek limestone (type exposure) above pavement and Hushpuckney shale above.

Plate IV--A--Drum limestone. Local cross-bedded limestone at the top. SE cor, sec. 31, T. 16 S., R. 24 E., Miami County. B--Characteristic Drum limestone at the middle of the west edge sec. 21, T. 17 S., R. 23 E., Miami County.

Bronson Group

The name Bronson was used by Adams for three principal limestones, and included shales. [Adams, G. I., U. S. Geol. Survey, Bull 238, pp, 17, 18, 1904.] above the "Dudley" shale in southeastern Kansas. At first he thought that the limestone should be correlated with the Hertha, Dennis, and Drum, but before the description of the Bronson was published he was acquainted with the true correlation of the units with which he was dealing and made the proper corrections in an inserted list of errata in this publication. Thus, Adams meant to include three principal limestones and contained shales in his Bronson up to the top of the Dennis limestone, or Winterset of modern writers.

Hertha Limestone

The name Hertha was introduced by Adams "for the limestones succeeding the upper Pleasanton shales as exposed in the vicinity of Hertha," Neosho county, Kansas. [Adams, G. I., in Adams, Girty, and White, Upper Carboniferous rocks of the Kansas section: U. S. Geol. Survey, Bull. 211, p. 35, 1903.] Jewett rightly concluded that the limestone to which the name Hertha was applied at Hertha by Adams in 1903 is the Bethany Falls limestone. [Jewett, J. M., Kansas Acad, Sci., Trans., vol. 36, p. 134, 1933.] It is possible to determine the exact bed at Hertha referred to by Adams in this publication because an areal map of eastern Kansas, showing the distribution of the Hertha and other limestone outcrops, accompanied the original definition.

A year after the first definition of Hertha, Adams published maps of the area immediately north of Hertha in which the first limestone below the Bethany Falls (= Mound Valley limestone) was indicated as Hertha. [Adams, G. I., in Adams, Haworth, and Crane, Economic geology of the Iola quadrangle, Kansas: U. S. Geol. Survey, Bull. 238, pp. 14 and 16, 1904.] This lower limestone is the six-foot limestone cropping out at Hertha, and not the one shown as Hertha in the previous publication. The reason for this confusing change in mapping was not given in the accompanying text. In the application of the term Hertha the early Kansas Survey followed this second usage of Adams so that, excepting for the original definition, the name Hertha has been consistently applied to the lower limestone of the Bronson group.

It was discovered by F. C. Greene, R. C. Moore, and me, in a special field investigation of the Hertha problem that the lower limestone cropping out at Hertha is continuous across eastern Kansas, and, contrary to Jewett's conclusion, it is in part equivalent to the limestone at Kansas City that has in the past been called Hertha. [Jewett, J. M., Kansas Acad, Sci., Trans., vol. 36, p. 134, 1933.]

It does not seem advisable to suppress the name Hertha on the grounds that it is a synonym of Bethany Falls. In Adam's final usage and subsequent work it appears that there has been a consistent application of the name to one limestone unit, the lower of the Bronson or "triple system" of the early writers. I propose here to retain the term Hertha in a formational sense for the limestone cropping out at Hertha, and for its immediate correlatives.

In tracing the Hertha southward from Kansas it was discovered by Greene, Moore, and me that the unit is added to above so that over much of eastern Kansas it is divisible into two members of unlike lithologic character, commonly separated by some shale. The upper member was thought to be Jewett's Schubert Creek limestone and the lower one, so well-developed in northeastern Kansas and adjoining parts of Missouri, is here termed the Sniabar limestone from exposures along Sniabar creek in southeastern Jackson county, Missouri. A characteristic exposure may be seen along the highway one half mile north of Knobtown, Jackson county, Missouri.

Lithologic character and thickness. The Sniabar limestone is exposed at a few places in the southeastern part of Miami County. It is commonly covered by the large slumped blocks of the Bethany Falls limestone above. The Sniabar limestone consists of thick-bedded, ferruginous, fine-grained limestone, generally drab or gray where fresh, and brown on weathered surfaces. The uppermost part of the limestone is granular and contains Osagia sp. readily visible on fresh surfaces. The member generally consists of a single bed of limestone, and only exceptionally are bedding planes shown. It averages six feet thick in Miami County, although at one locality in sec. 10, T. 19 S., R. 24 E., it is only five feet thick. The unit is rather unfossiliferous. A careful search in Miami County for fusulinids in the Sniabar limestone has been fruitless.

Distribution. The outcrop of the Sniabar limestone is restricted in Miami County to the (1) valley of Sugar creek and the lower part of its principal tributaries, (2) the lower part of Middle creek, (3) the valley of Marais des Cygnes river, extending to the northeast part of township 18 south, range 23 east, and (4) Hushpuckney creek valley in township 19 south, range 23 east. The formation does not crop out in Johnson County.

Detailed sections. Sections of the Sniabar limestone are given under numbers 122, 124, 125, 152, 157, 158, and 159 in the register at the end of the report.

Ladore Shale

The term Ladore was applied by Adams to the shale between the Hertha and Mound Valley (Bethany Falls) limestones as shown near Ladore. [Adams, G. I., in Adams, Haworth, and Crane, U. S. Geol. Survey, Bull. 238, map opposite p. 14, 1904.] Since the upper limestone layers of the Hertha appear generally to be lacking in northeastern Kansas, the Ladore shale may include slightly lower beds than in southern Kansas, but, on the other hand, Middle Creek limestone and overlying Hushpuckney shale which may be represented by the upper Ladore in southern sections are excluded from the Ladore in the north. The Ladore shale of northeastern Kansas is not nearly as thick as it is in southeastern Kansas.

Lithologic character and thickness: The Ladore shale crops out in Miami County, where it consists chiefly of buff to gray argillaceous shale. Generally the lower part is limy and nodular. The upper portion locally contains thin lenticular shaly limestones, but more commonly it is argillaceous throughout. The formation ranges in thickness from five to twelve feet, but averages about five and one half feet. A typical section at the west edge of the NE of sec. 10, T. 19 S., R. 23 E. shows two feet of greenish-buff, limy shale, overlain by five inches of soft, gray, argillaceous limestone, and three feet three inches of argillaceous, gray shale with a thin limestone at the middle. The formation is relatively thick at the middle of the south edge of sec. 18, T. 18 S., R. 24 E., where it reaches a thickness of twelve feet.

Swope Limestone

The term Swope, from Swope Park, Kansas City, Mo., is proposed by Moore and Newell for the persistent limestones and thin shales from the top of the Ladore shale to the top of the Bethany Falls limestone. The units of the Swope are, in ascending order: Middle creek limestone, Hushpuckney shale, and Bethany Falls limestone.

Lithologic character and thickness. The lowest member of the Swope, the Middle creek limestone, is named from the exposures on the east side of Middle Creek at the highway three miles east of La Cygne, Linn County, Kansas. The member is exceedingly uniform throughout Kansas and Missouri. It consists generally in Miami County of two even layers of dark bluish-gray, dense, and brittle limestone. Only locally in the area are the two layers separated by shale, as at the west edge of the NE sec. 10, T. 19 S., R. 23 E., where the section from the base upward is one and one half feet of bluish-gray, lithographic even limestone, five inches of limy buff shale with batostomellids, overlain by four and one half inches of bluish-gray dense limestone. At some localities the upper surface of the lower bed of the Middle Creek limestone is covered with a peculiar twig-like form which recalls certain types of the alga Lithothamnion. The member is quite uniform in thickness, ranging in this region from about one foot four inches to a maximum of two feet three inches. Where there is no included shale the Middle Creek is commonly one foot eight inches thick. The Middle Creek limestone strikingly duplicates in its physical characters and in its> position immediately beneath black fissile shale the "middle limestone" members of the limestone formations in the Shawnee group, where Moore has defined the typical sequence of units in regularly repeated sedimentation cycles. In terms of this cycle, therefore, the Middle Creek member may be classed as a "middle limestone."

The Hushpuckney shale, here named from a creek south of Fontana, in Miami County, is similar to many of the thin carbonaceous shales in the Mid-Continent region. It is typically shown at a railroad cut, center north side sec. 13, T. 19 S., R. 23 E. (Loc. 124). It consists typically of two parts, the upper half being gray, argillaceous shale, and the lower half black, platy shale. Locally a thin layer of argillaceous, greenish shale underlies the black shale, and less commonly the upper part of the member consists of carbonaceous, blocky shale. The carbonaceous parts of the unit are not very fossiliferous, but in places they yield orbiculoid brachiopods. At Middle creek, about one fourth of a mile east of the SW cor. sec. 22, T. 18 S., R. 24 E., a few impressions of the scales of a large ganoid fish occur in the black platy shale. Small phosphatic nodules are rather common in the carbonaceous part of the shale. The thickness of the Hushpuckney member ranges from four and one half to five and one half feet, the average being closer to the latter figure.

The Bethany Falls limestone, named by Broadhead from exposures at the falls of Big creek, near Bethany, Mo., is an easily recognized unit where it is fairly well exposed. [Broadhead, G. C., Coal Measures in Missouri: St. Louis Acad. Sci., Trans., vol. 2, p, 320, 1868 (read May 5, 1862, first issued July 27, 1865).] The member in Miami County is similar to exposures in the vicinity of Kansas City and elsewhere in eastern Kansas. The upper part is massive, drab or light gray, oolitic, and cross-bedded. Locally, there is a thin layer of loose limestone nodules at the top. The uppermost part of the massive bed is at a few places mottled with bluish-gray spots. The oolitic part is quite unfossiliferous, and locally contains peculiar vertical tubular cavities measuring as much as five feet in length by two inches in diameter. Generally the cavities are lined by iron-stained calcite crystals, and less commonly they are nearly or entirely filled with calcite. Where the rock is weathered the oolitic grains have in most cases been removed by solution, leaving minute spherical cavities surrounded by the limestone matrix. The massive upper part of the Bethany Falls weathers in great rounded masses, which creep down the slopes in huge blocks, or it crops out as a massive ledge along valley slopes. There is considerable variation in the thickness of this part of the member. It ranges from about one foot at the center of the south edge of sec. 18, T. 18 S., R. 24 E., to thirteen feet at the west edge of the NE sec. 10, T. 19 S., R. 23 E. In fact, most of the variation in thickness of the member is due to the irregularity of the oolitic part. The upper massive part of the Bethany Falls is commonly about seven feet thick.

The lower part of the member is quite distinct from the upper. It is composed of thin-bedded, even, whitish or light-gray limestone, containing an occasional light-colored chert nodule and a few brachiopods of the Productus type. A small fusulinid of the appearance of Triticites irregularis occurs here, the first appearance of Triticites in the section. This limestone generally weathers buff, especially below, where occur a few thin shale partings. This part of the member ranges between ten and nineteen feet, but most commonly measures about fourteen feet. The greatest thickness of the entire member in Miami County was measured at the west edge of the NE sec. 10, T. 19 S., R. 23 E., where it is twenty-seven feet thick. The member is thinnest at the center of the north edge of sec. 13, T. 19 S., R. 23 E., at a railroad cut, where it measures thirteen feet. Generally the member measures about eighteen feet in Miami County.

The lower thin-bedded Triticites-bearing part of the Bethany Falls member is entirely similar in physical and faunal characters and in its position above black platy shale to the so-called "upper limestone" of the limestone formations in the Shawnee group. The remaining upper part of the Bethany Falls, which is irregular in thickness and in various portions massive, oolitic, or nodular, is probably chiefly of algal origin. It duplicates characters that are typical of what Moore has termed the "super limestones" in the sedimentary cycle exhibited by the Shawnee group limestone formations. The Bethany Falls limestone thus contains both the "upper" and "super" elements of the cyclic succession of beds as described by Moore.

The outcrops of the Bethany Falls limestone extends into Johnson County from Missouri for a short distance along the lower part of Indian creek. Only the upper part of the member is exposed on the Kansas side. Very good exposures of the entire Swope formation occur a short distance to the east along Big Blue river in Jackson county, Missouri. The Bethany Falls limestone, which is the oldest member exposed in Johnson County, shows the characteristic features at the Indian creek exposure. It weathers in large, rounded masses, displaying few joints. The upper few feet of the member consists of drab, soft, highly nodular and rather unfossiliferous limestone. In near-by areas where the entire member is exposed, the upper part of the Bethany Falls is very massive and is oolitic or nodular. This part of the formation has a tendency to form large slumped blocks which hide the lower and less massive part. This peculiar feature of weathering is excellently displayed in the outcrops in Swope Park in Kansas City and to the southward along the valley of the Big Blue. The lower part of the Bethany Falls in the Jackson county exposures resembles the exposures in Miami County, consisting of even-bedded, gray limestone with a few thin shale partings. The entire Swope limestone is about twenty feet thick in the exposures nearest the Johnson County line.

Distribution. The Swope formation crops out in Miami County along the principal streams in the southeastern part. On Sugar and Middle creeks it extends to about the middle of township 18 south, and along Marais des Cygnes river to a point west of the center of township 18 south, range 23 east, where it is seen at the water's edge beneath the highway bridge in section 17. On Mound creek, southeast of Beagle, the formation is exposed as far as the western edge of range 23 east.

In Johnson County the Swope limestone is exposed near stream level on Indian creek at the state line. At other places in the county it is covered by younger formations.

Detailed sections. Sections of the Swope are given under numbers 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 130, 152, 154, 157, 158, and 159.

Galesburg Shale

The Galesburg shale was named by Adams from Galesburg, Neosho county, Kansas. [Adams, G. I., Stratigraphy and paleontology of the Upper Carboniferous rocks of the Kansas section: U. S. Geol. Survey, Bull. 211, p. 36, 1903.] According to Adams' original definition, it includes "the rocks occupying the interval between the Hertha limestone and the Dennis limestone." It has been generally assumed that Adams overlooked the Bethany Falls limestone at Galesburg, since that formation lies between the Hertha and the Dennis. Because the term Ladore was used for the shale between the Hertha and Bethany Falls the name Galesburg was restricted by the early Kansas Survey to apply to the strata between the Mound Valley (Bethany Falls) and the Dennis limestones.

In southeastern Kansas, extending as far north as Linn County, there is a thin, blocky, blue limestone below the Winterset limestone, separated from it by a thin black shale. This limestone was known to the older writers and to Hinds and Greene. [Hinds, Henry, and Greene, F. C., The stratigraphy of the Pennsylvanian series in Missouri: Missouri Bur. Geol. and Mines, vol. 13, 2d ser., Table Opp. p. 119, 1915.] Jewett has determined that the limestone is absent in northern Linn County and that it makes its appearance to the southward. This limestone, called Canville by Jewett, and the black shale above lie at the horizon of the upper part of the so-called Galesburg in the Kansas City region. In northeastern Kansas the section above the Bethany Falls is as follows: a thin layer of buff or gray clay shale is overlain by two or three feet of black fissile shale, which is in turn overlain by a thin layer of buff or gray clay. The Winterset overlies this clastic succession.

According to Jewett, the situation at Galesburg is as follows. A thick shale and sandstone section, the Galesburg shale, is overlain by a limestone formation which consists of three parts; a lower thin, blocky limestone, overlain by a thin shale containing a layer of black fissile shale, succeeded by a thick limestone. The older writers did not mention any limestone or black shale in the typical Galesburg, and it is almost certain that the rather obscure black shale layer and basal limestone were grouped with the main limestone above under the term Dennis. This succession, which occurs at Dennis as well as Galesburg, is not easily recognized at all exposures because the lower units are commonly hidden by slumped blocks of the much thicker upper member.

The shale below the thin basal limestone has thinned in the vicinity of Uniontown from over seventy feet to about ten feet. Farther north the unit thins even more, to less than three feet in Miami County. The view is here taken that this shale in Miami County is the true Galesburg shale, on the basis of stratigraphic continuity and because the black shale above, which in southeastern Kansas is underlain by a thin limestone, belongs genetically with the limestone above. The thin blocky limestone is replaced by shale to the northward, so that in Miami and Johnson counties the Galesburg is directly overlain by the black shale which Jewett has called the Stark shale. The Canville limestone and Stark shale are classed with the Winterset limestone as members of the Dennis limestone.

Lithologic character and thickness. The Galesburg is fairly uniform in its characters in Miami County. The unit is underlain by the Bethany Falls member of the Swope and overlain by black fissile shale, the Stark. A characteristic section of the Galesburg occurs two and one half miles east of La Cygne, Linn County. From the base upward there is two feet four inches of buff, limy, nodular shale, and four inches of buff, limy, hard shale, rarely bearing Leiorhynchus rockymountanum. The hard shale is probably the equivalent of the dense, blue Canville limestone that occurs at this horizon a short distance to the south.

The Galesburg is not well exposed in Johnson County and, like the Bethany Falls, crops out only at the NW cor. sec. 11, T. 12 S, R. 25 E., in the bed of Indian creek. The formation is generally about two feet thick in near-by areas and becomes increasingly argillaceous and less calcareous toward Kansas City.

Distribution. In Miami County the formation crops out along the major streams in the southern part of the county. The Galesburg extends along the forks of Sugar creek almost to the middle of township 18 south. It crops out along Middle creek to a point north of the center of township 18 south, range 24 east, and extends nearly to the west edge of range 23 east on Marais des Cygnes river, where the formation dips below the plain southeast of Henson. On Mound creek the Galesburg crops out upstream to about the west edge of range 23 east.

The only occurrence of the Galesburg in Johnson County is given above.

Detailed sections. Sections of the Galesburg are given under locality numbers 121, 122, 123, 124, 130, 152, 154, and 159.

Dennis Limestone

The term Dennis, from a town in Labette county, Kansas, was applied by Adams to a formation which he considered to be the same as the previously named Mound Valley limestone. [Adams, G. I., Stratigraphy and paleontology of the Upper Carboniferous rocks of the Kansas section: U. S. Geol. Survey, Bull. 211, p. 36, 1903.] The Kansas Survey, however, maintained that the Mound Valley, or Bethany Falls of modern writers, and the Dennis were different formations. Later it was found that the Winterset limestone of Iowa geologists could be correlated with the Dennis, and the older term Winterset was retained. [Tilton, J. L., and Bain, H. F., Geology of Madison county: Iowa Geol. Survey, vol. 7, pp. 517-519, 1897.] As explained under the discussion of the Galesburg, Jewett has found that the type Dennis consists of more than the Winterset limestone as interpreted by Missouri geologists. The limestone at Dennis contains three divisions. These are a basal, blocky, thin limestone, overlain by black fissile shale, and thick limestone. This is a duplication of the cycle exhibited by the Swope limestone. The basal limestone at Dennis extends northward along the outcrop as far as southern Linn County, beyond which it changes to limy shale. The black shale member, which Jewett calls the Stark, from a town in Neosho county, has always been considered a part of the Galesburg in the Kansas City region. [Jewett, J. M., Kansas Acad. Sci., Trans., vol. 36, p. 133, 1938.] In northeastern Kansas, including Johnson and Miami counties, the Stark is the lowermost member of the Dennis formation, since the basal limestone found in southeastern Kansas is unrecognizable in the northern area. The uppermost and most persistent member is the Winterset of standard usage. The Dennis formation as here used includes in northeastern Kansas the Stark shale below and the Winterset limestone above. In southeastern Kansas a third member, a basal, thin limestone, the Canville, occurs below the Stark. [Jewett, J. M., Kansas Acad. Sci., Trans., vol. 36, p. 133, 1938.]

Lithologic character and thickness. The Stark shale, lowermost member of the Dennis in northeastern Kansas, is generally quite uniform. It consists of black fissile shale below, overlain by a slightly thicker amount of gray or buff argillaceous shale. In Miami County the carbonaceous part of the member is two and one half to three feet thick and contains an abundance of phosphatic concretions. The upper part of the member consists of four and one half feet of buff and gray limy shale.

The member presents about the same character at the few outcrops in Johnson County. The upper part of the member is generally yellowish and underlain by gray argillaceous shale. The entire unit is about four feet at exposures in eastern Johnson County and adjoining parts of Missouri.

The Winterset limestone is more regular in Miami and Johnson counties than the Bethany Falls, with which it might be confused, but has characters less striking. In both counties the Winterset consists of gray, thin-bedded, even limestone, fine-grained or dense at the middle and veined or coarse below. In Miami County the uppermost part consists of dark-gray or nearly black, fine-grained limestone bearing a characteristic faunal assemblage. At one locality, just west of the NE cor. section. 11, T. 18 S., R. 23 E., a relatively thick shale parting was observed near the top of the formation. Elsewhere the member seems to be rather free from shale. Near the top and especially at the middle part there are generally a great many large chert nodules. Locally these may be dark-gray or black, but in Miami County they are mostly buff, brown, or gray. Near the top and below the black limestone stratum a thin layer of oolite, with a few oolitic chert nodules, is observed in many places. Locally below the oolite there are a few thin layers of light-gray, lithographic, siliceous limestone, containing a few silicified pleurotomarids. The lower part of the member is somewhat thicker bedded and consists of dark-gray, fine-grained, veined limestone. The upper part of the member in Miami bears a prolific fauna, consisting chiefly of Triticites irregularis, Derbya cf. crassa, Juresania nebraskensis, and a very large variety of Composita. The fauna of the lower part of the Winterset includes several productids. The member is about thirty feet thick in Miami County.

There are no good exposures of the Winterset limestone in Johnson County. The member crops out for a short distance in the county along Turkey and Indian creeks. The rock is dove-gray for the most part, somewhat argillaceous, even-bedded, and contains a few scattered nodules of black flint near the top. A short distance to the east along Big Blue river in Missouri, in the vicinity of Martin City and elsewhere, the upper part of the Winterset is oolitic and might easily be mistaken for a local facies of the Westerville limestone. In the northern part of Johnson County a prolific molluscan fauna occurs at the top of the member, but the rock is only obscurely oolitic. The complete thickness of the member cannot be measured in Johnson County. A short distance into Missouri it measures a little more than twenty-five feet in thickness.

As was noted in describing the Swope formation, it is easy also to recognize units in the Dennis formation that correspond to the "middle," "upper," and "super" limestones of the Shawnee limestone formations. The Canville limestone is a characteristic "middle." At most outcrops in Johnson and Miami counties the Winterset limestone is an "upper," but where the oolitic limestone is present at the top of the Winterset the "super" also is represented. The Dennis limestone may thus be recognized as containing most of the units of the sedimentation cycle (all of the limestones but the "lower") that are found in the Shawnee group.

Distribution. The Dennis formation crops out in the southeastern part of Miami County along Sugar and Middle creeks for a short distance above the middle of township 18 south, and along Marais des Cygnes river to the west edge of range 23 east. On Mound creek the formation dips beneath the flood plain south of Beagle.

The outcrop of the formation in Johnson County is confined to the middle of the east edge, along Indian creek, and the uppermost part of the Winterset is exposed in the' bed of Turkey creek near the northern line of the county.

Detailed sections. See locality numbers 67, 68, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 127, 129, 150, 152, 153, 154, and 159.

Kansas City Group

In the reclassification of the Pennsylvanian of the northern Mid-Continent, Moore proposes to restrict the term Kansas City to the irregular and dominantly shaly strata between the Dennis and Plattsburg formations. [Moore, R. C., Kansas Geol. Soc., Guidebook 6th Ann. Field Conference, p. 91-92, 1932.] The Kansas City contrasts strikingly in its greater irregularity with the exceedingly persistent divisions of the Bronson and Lansing groups. The Kansas City group as redefined contains, in ascending order, the Fontana shale, Block limestone, Wea shale, Westerville limestone, Quivira shale, Drum limestone, Chanute shale, Iola limestone, Lane shale, Wyandotte limestone, and Bonner Springs shale. The strata between the top of the Winterset and the base of the Drum limestone are apparently the correlatives of the Cherryvale shale of southeastern Kansas.

The Cherryvale shale was named by Haworth for the thick shale between the Winterset and the Drum limestone at Cherryvale, Kan. [Haworth, E., Stratigraphy of the Kansas Coal Measures: Kansas Univ. Geol. Survey, vol. 3, p. 483, 1896.]

The strata at Kansas City for so long classed as Cherryvale are the equivalent of the lower part of the typical Cherryvale. This miscorrelation is one of the results of the misidentification of the Drum limestone in northeastern Kansas. This will be discussed more fully under the description of the Drum limestone. The unit called Cement City in the Kansas City region is the equivalent of the lower part of the Drum limestone of southeastern Kansas. [Hinds, Henry, and Greene, F. C., The stratigraphy of the Pennsylvanian series in Missouri: Missouri Bur. Geol. and Mines, vol. 13, 2d ser., Table Opp. p. 27, 1915.] The outcrop is continuous across Kansas and no place is known where the Cement City is less than one foot thick. [Recent work proves that the Central City locally cut out by unconformity in southeastern Kansas.] Between Paola and Cherryvale, Kan., it is generally less than six feet thick.

The Westerville limestone, or "Kansas City oolite," for so long erroneously correlated with the Drum limestone because of a similar local fauna and lithologic facies, extends no farther to the southwest than Martin City, Jackson county, Missouri, and is equivalent to part of the Cherryvale, since it lies below the Cement City member of the Drum.

In Miami County there occurs a limestone bed of some prominence about fifteen feet, more or less, above the Winterset. This limestone, here called Block after a hamlet in Miami County, has considerable persistence throughout northeast Kansas and adjoining parts of Missouri.

The Block and Westerville limestone provide a five-fold division in northeastern Kansas apparently corresponding to the Cherryvale interval. In order from older to younger these are: Fontana shale, Block limestone, Wea shale, Westerville limestone, and Quivira shale.

The exact limits of Cherryvale equivalents in northeastern Kansas and Missouri may be open to some question, as suggested to me by Moore, on the following basis. In the bluffs west of Coffeyville, Kan., the Winterset limestone is overlain immediately by thin-bedded, bluish, flaggy limestone typical of one variety of "super" bed of the limestone cycle. The Winterset in this area, so far as yet known, does not contain limestone of the "super" type. Northward toward Cherryvale the bluish Baggy limestone beds seem to diverge greatly from the Winterset so that the genetic relationship between these beds and the Winterset is obscure. To the northward from Cherryvale the Baggy beds disappear. It is Moore's suggestion that they may correlate with the oolitic "super" rock which appears in the Winterset in northeastern Kansas. If this interpretation can be demonstrated the greater part of the type Cherryvale shale might be included in the Winterset limestone.

Fontana Shale

The term Fontana is employed here for the fifteen-foot argillaceous shale immediately above the Winterset limestone in the vicinity of Fontana, Miami County, Kansas. Typical exposures occur in road cuts at the NE cor. sec. 11, T. 18 S., R. 23 E., and at the middle of the west side of the NW of sec. 36, T. 18 S., R. 23 E., near Fontana.

Lithologic character and thickness. In Miami County the formation is quite uniform, exhibiting but little variation in lithologic character or thickness. Wherever it is exposed it is a greenish-gray or buff argillaceous shale, and generally contains a few widely scattered and very small calcareous nodules. At one locality, a road-cut west of the NE cor. sec. 11, T. 18 S., R. 23 E., a thin layer of ferruginous, limy shale occurs near the base. The formation is relatively barren of fossils. The minimum thickness measured was at a locality one fourth of a mile west of the center of the west edge of sec. 18, T. 19 S., R. 23 E., where the formation is twelve feet thick. The greatest observed thickness of eighteen feet occurs at the center of the west edge of the NW of sec. 36, T. 18 S., R. 23 E.

The Fontana shale is considerably thinner in Johnson County than it is to the south. In fact, there seems to be a more or less uniform thickening of the member from Kansas City, where it is about five feet, to northern Linn County, where it is over twenty-five feet thick. The Fontana is poorly exposed in Johnson County, cropping out only along the lower parts of Big Blue river, Indian creek, and Turkey creek. In southeastern Johnson County it consists of argillaceous, gray or buff shale, ranging in thickness from six to ten feet. A characteristic zone of Chonetina flemingi var. plebeia Dunbar and Condra occurs at the top of the shale wherever it is exposed in Johnson County and in the Kansas City region. In the northern part of Johnson County the Fontana is generally buff and somewhat limy with occasional nodules of limestone. In this area the formation is about six feet thick.

Distribution. The Fontana shale crops out in Miami County for a short distance up the eastward flowing streams near the state line in township 16 south, range 25 east. In the southern part of the county the Fontana crops out to the middle of township 18 south on the branches of Sugar creek, and to the northeast part of township 18 south, range 24 east along Middle creek. On Marais des Cygnes river the shale crops out along the valley walls to Osawatomie and extends a short distance above the fork of Wea and Bull creeks at Paola. The formation crops out along Mound creek to a point south and west of Beagle.

In Johnson County the Fontana shale is generally not well exposed. Consequently its surface distribution must be inferred largely from the outcrop of the Winterset limestone. The outcrop of the Fontana is restricted to the valley of Big Blue river in township 14 south, range 25 east, an area along Kansas river east of Holliday, the valley of Indian creek, in township 13 south, range 25 east, and Turkey creek in township 12 south, range 25 east.

Detailed sections. For sections including the Fontana shale see the following numbers at the end of this report: 40, 67, 68, 117, 120, 127, 129, 150, 153.

Block Limestone

The term Block limestone is here introduced for a thin limestone about fifteen feet above the Winterset limestone cropping out just east of the hamlet of Block in eastern Miami County. In northern Linn and Miami counties this limestone is a fairly prominent unit, attaining a thickness of five feet or more. It thins northward somewhat and splits into several thin beds of limestone, separated by limy shale. The Block includes practically all of the limestone in the lower part of the so-called Cherryvale shale at Kansas City. According to observations by R. C. Moore, this limestone is a compact, clearly recognizable unit near Gallatin and Bethany in northern Missouri, and it probably extends into Iowa.

Lithologic character and thickness. This formation is uniform in Miami County, in contrast to its irregularity in Johnson County. It is characteristically composed of bluish-gray, even, thin-bedded limestone with a few thin, fossiliferous shale partings which are locally absent. Upon weathering the limestone becomes broken into blocky, angular fragments having a light-gray color. The texture of the rock is fine-grained or sugary. There are no particularly characteristic fossils, but Marginifera wabashensis and Triticites irregularis were noticed at several localities. The Block limestone ranges in thickness from three to eight feet, but is not as irregular as this would suggest, since in most places it is generally about four feet thick. A thickness of three feet was observed at the east side of the NE of sec. 15, T. 19 S., R. 22. E. The greatest thickness of eight feet occurs at a locality one fourth of a mile west of the middle of the west edge of sec. 18, T. 19 S., R 23 E. Where the formation is unusually thin it has little or no included shale.

In Johnson County the Block limestone splits up into two or more thin, lenticular, buff limestones, separated by thin shaly partings. It is difficult to correlate these separate limestone beds from place to place, but the base of the lower one is well marked by a persistent zone of Chonetina flemingi var. plebeia Dunbar and Condra. Since these thin limestones are always closely associated and include about all of the limestone between the Winterset and Westerville, it seems logical to assume that they mark the northern extension of the Block limestone. The most southern outcrop of the Block limestone in Johnson County occurs at the SE cor. sec. 10, T. 14 S., R. 25 E. At this place the Chonetina zone underlies a six-inch blocky limestone that resembles in color and texture the Block limestone in Miami County. Apparently there is no more limestone between this thin bed and the Westerville limestone above. The Winterset is not exposed here but crops out a short distance downstream.

Distribution. The Block limestone crops out in eastern Miami County for a short distance up the principal eastward-flowing creeks in township 16 south, range 25 east. In the southern part of the county the member extends to the middle of township 18 south on the main forks of Sugar creek. Along Middle creek the outcrop reaches into section 12, township 18 south, range 24 east. On Marais des Cygnes river and the Pottawatomie the formation crops out as far west as Osawatomie. Along Mound creek it extends to the middle of range 22 east.

In Johnson County the outcrop of the Block is coextensive with that of the Fontana shale; that is, along the lower part of Big Blue river, Indian creek, Turkey creek, and along Kansas river east of Holliday.

Detailed sections. For sections of the Block limestone see numbers 40, 67, 98, 101, 117, 120, 127, 129, 131, 134, 143, 150, and 153, at the end of this report.

Wea Shale

The term Wea shale from Wea creek in northeastern Miami County is here employed for a shale bed between the Block limestone and the black Quivira shale above. In Johnson County the Westerville limestone separates the Wea and Quivira, but in Miami County the Westerville is only locally present. The Wea is typically exposed at the SE cor. of sec. 31, T. 16 S., R. 24 E. (sec. 166) and at the center of the east side of sec. 12, T. 18 S., R. 22 E. (sec. 129). Since the Westerville limestone disappears in southwestern Jackson county, Missouri, it is possible that the Wea shale in Miami County is the equivalent of the Westerville limestone and the shale below it in the Kansas City region. There is evidence, on the-other hand, that the Westerville is entirely younger than the Wea shale. The limestone does not grade laterally into shale but pinches out rather abruptly. Also there are deposits of conglomerate and indications of at least local disconformity at this horizon in northwestern Miami County. In any case, the Wea shale is a distinct lithologic unit.

The Wea shale is somewhat irregular in Miami County. It consists mostly of olive-green argillaceous shale. Locally, as at the NW cor. of sec. 7, T. 18 S., R. 25 E., there is a thin layer of maroon shale near the top. Excepting one place, the Westerville limestone is absent in Miami County, so that the Wea is in direct contact with the black Quivira shale. The single exception occurs at the locality given just above. Here the Westerville consists of two feet four inches of conglomeratic, thinly cross-bedded limestone. South and west of Paola the Quivira shale loses its characteristic black or maroon color and cannot be distinguished from the Wea. In this case, the two shales may be classed together as the Wea-Quivira shale. A thin sandstone occurs above the middle of the Wea at the south side of the SW sec. 6, T. 18 S., R. 24 E., where the greatest thickness of the Wea-Quivira was measured. The maximum thickness of about twenty-two feet was measured for the Wea at the center of the east edge of sec. 12, T. 18 S., R. 22 E. The Wea shale varies in thickness from place to place in Miami County with little or no regularity.

The Wea shale in southeastern Johnson County consists of argillaceous shale with an increase in calcareous material toward the north. The thickness ranges from about ten to over thirty feet, the greatest thickness being along Indian creek and Big Blue river in the eastern part of the county.

Distribution. In Miami County the Wea shale crops out in the eastern and southern parts of the area in a band nearly coextensive with the outcrop of the Block limestone.

As in the case of the Fontana shale, the Wea is poorly exposed in Johnson County, consequently the distribution is best inferred from the outcrop of the Westerville and Winterset limestones. The Wea shale is exposed along Big Blue river in township 14 south, range 25 east, along Kansas river below Holliday, along Indian creek in township 13 south, range 25 east, and on Turkey creek in township 12 south, range 25 east.

Detailed sections. Sections of the Wea shale are given under 37, 38, 40, 55, 66, 67, 68, 98, 99, 101, 106, 109, 117, 129, 131, 132, 136, 142, 150, 155, 161, and 166 at the end of this report.

Westerville Limestone

The Westerville limestones was named by Bain from Westerville, Iowa. [Bain, H. F., Am. Jour. Sci., 4th ser., vol. 5, pp. 437, 439, 1898.] For many years an oolitic limestone at Kansas City has been erroneously correlated with the Drum limestone of southeastern Kansas. The correlation has been made chiefly on faunal grounds and lithologic similarity, in spite of the well-known fact that facies faunas like those found in oolitic limestones cannot generally be employed for exact correlations. In recent years the Nebraska Survey has correlated the so-called Drum limestone at Kansas City with the Dekalb of Iowa. [Bain, H. F., Geology of Decatur county; Iowa Geol. Survey, vol. 8, p. 278, 1897.] Since Dekalb antedates Drum there has been a tendency to drop the term Drum in recent publications. In October, 1932, Dr. R. C. Moore, in company with Dr. G. E. Condra and Dr. F. C. Greene, traced the so-called Drum limestone of the Kansas City area to Winterset, Iowa. They determined that the type Dekalb limestone is the Winterset limestone. The latter name being the oldest, the term Dekalb must be dropped. They also found by study of exposures near Westerville that Bain's Westerville limestone is the same as that called Drum limestone at Kansas City.

Successful attempts have not been made in the past to trace the outcrop of the Westerville southward to the type region of the Drum. Although there is no considerable difficulty attendant to tracing it southward from Kansas City, the Missouri geologists were led into error by overlooking the fact that the Westerville limestone abruptly changes to shale or pinches out at Martin City, Jackson county, Missouri.

The oolitic facies of the upper part of the Westerville at various localities in Kansas City has long been considered highly characteristic of the unit as a whole. Actually few of the exposures in southern Kansas City, Missouri, show the oolitic facies. The nonoolitic lower part of the Westerville, locally called the "Bull ledge," is the most persistent part of the formation and retains its characters fairly well, whereas the upper part is highly irregular or absent.

The most recent published work involving the Westerville limestone in Kansas is a faunal study by Sayre which treats of the stratigraphy in rather an incidental manner. [Sayre, A. N., Fauna of the Drum limestone: Kansas Geol. Survey, Bull. 17, 1930.] Sayre was misled in several instances by his conviction that the oolitic facies is characteristic of the Drum limestone across Kansas. He erroneously correlated the limestone at Kansas City, here called Westerville, with the typical Drum, and at some localities he mistook the oolitic portions of the Bethany Falls and Winterset limestones for the Drum.

The Westerville is one of the most variable units cropping out in Johnson County. Where it is thick it is oolitic and cross-bedded, and where it is thin the formation is very massive and even-bedded, and commonly nonoolitic, In the northern part of Johnson County the upper part of the Westerville consists of thin beds of alternating shale and limestone. The formation ranges in thickness from over twenty feet in section 35, T. 12 S., R. 25 E., to four feet along Big Blue river. The greatest variation takes place apparently in Ts. 12 and 13 S., R. 25 E., and in T. 12 S., R. 23 E. Near the highway just east of Holliday at the creek bridge, the Westerville is fairly well exposed. The upper nine feet consists of gray, calcerous shale and interbedded limestone. After comparing this exposure with the section at the quarry near Morris, Wyandotte County, the upper contact of the Westerville was placed considerably above the main limestone bed, the latter actually representing only the lower part of the formation. The main limestone of the Westerville at Holliday consists of very fossiliferous oolite, underlain by a foot or so of hard, gray limestone. The exposure just off the intersection of the highway with the county line, at the middle of the north edge of sec. 6, T. 12 S., R. 24 E., resembles the exposures at Morris and Holliday. At a quarry near the state line, NW cor. sec. 35, T. 12 S., R. 25 E., the Westerville is unusually thick, although the beds above it are characteristic. At this place the formation consists of about twenty feet of oolitic limestone, cross-bedded on a large scale. The limestone is here rather unfossiliferous, although the Cement City limestone above it is quite fossiliferous. According to drill records at this locality, the Winterset limestone seems to lie unusually close to the base of the Westerville. At a creek bridge near the NW cor. of sec. 15, T. 13 S., R. 25 E., the Westerville is a massive, gray limestone, dense, weathers drab, and has a thickness of four feet. The identification rests on the characteristic aspect of the overlying beds. Eight feet of fossiliferous cross-bedded oolite are exposed at a creek crossing, NW cor. sec. 25, T. 12 S., R. 23 E. The bed is too poorly exposed to determine its relative position in the Westerville, but it is probably the exact equivalent of the oolite at Holliday. At a road cut near the SE cor. sec. 34, T. 13 S., R. 25 E., the Westerville is a four and one half foot bed of dark-gray, massive limestone.

In much of southeastern Johnson County and adjoining parts of Jackson county, Missouri, the Westerville limestone resembles very closely the Cement City member of the Drum limestone of the same region. In some exposures the only characteristic difference is in the fossil content. A large variety of Triticites is sparsely distributed through the Westerville (nonoolitic part) but is totally lacking in the Drum. A variety of Campophyllum torquium occurring sparsely in the formation is highly characteristic of the Drum in northeastern Kansas and is lacking from the Westerville.

A fine exposure including strata from the Winterset to the Drum occurs about three and one half miles northeast of Martin City, Jackson county, Missouri. The exposure is seen at a road cut just east of the intersection of the paved roads 1-E and 10-S, about one fourth of a mile east of an entrance to Red Bridge Farm. At this place the Westerville and Drum are each about five feet thick, separated by the characteristic greenish Quivira shale containing a thin carbonaceous layer near the middle. A similar development is seen one half of a mile north and one half mile east of Martin City, about a half mile east of the highway intersection. A maroon layer near the base of the Chanute shale affords a convenient key; horizon in this region. At a bluff south of a creek at the pavement intersection two miles south of Martin City, the Westerville limestone is gone, represented only by a few limestone concretion at the base of the black Quivira shale.

Farther to the southwest in Miami County, the Westerville limestone is entirely missing except for one isolated locality, one fourth of a mile south of the NW cor. of sec. 7, T. 18 S., R. 25 E. At this place a gray, conglomeratic, thin-bedded limestone occurs below the black shale of the Quivira. The thickness of the Westerville lentil is about two feet four inches. About five and one half feet below this limestone at the above locality there occurs a thin local layer of maroon clay.

Distribution. The Westerville limestone extends only a short distance west of Holliday before dipping below the flood plain of Kansas river. Rather surprisingly the outcrop of the member extends far up Mill creek to sec. 35, T. 12 S., R. 23 E., indicating a structural "high" in the lower drainage of the stream. The formation crops out along Turkey creek as far upstream as sec. 5, T. 12 S., R. 25 E., but no good exposures of the Westerville are encountered in this area. A small outcrop of this limestone occurs on Brush creek, secs. 2, 3, and 10, T. 12 S., R. 25 E. The Westerville is well exposed on the valley in secs. 30, 27, 26, and M, T. 12 S., R. 25 E., but since it is the lowest bed cropping out along the creek within the county, the outcrop extends upstream but a short distance. The Westerville is fairly well exposed along Big Blue river for a short distance from the state boundary. In other parts of Johnson County the formation is buried beneath younger sediments.

As already noted, the Westerville limestone has been found at only one place in Miami County.

Detailed sections. Sections of the Westerville limestone are given at the end of the report under numbers 1, 8, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43, 48, 50, 52, 55, 65, 66, 67, 68, and 161.

Quivira Shale

The term Quivira, after Quivira Lake on Kansas river east of Holliday where the formation is exposed below the dam, is applied here to the thin argillaceous and bituminous shale lying between the Westerville and Cement City limestones. The formation is also typically shown at the east edge of Holliday, Kan. This unit was erroneously considered to be the lower part of the Chanute shale by Missouri geologists. Since, however, it rests beneath the Cement City member of the Drum, the Quivira is the equivalent to the upper part of the type Cherryvale shale.

The Quivira is somewhat irregular in Miami County, but has characters so striking that it can be readily identified. With but a few exceptions the bed has at the base either a thin layer of black carbonaceous shale or a streak of maroon clay. These two kinds of shale occur at nearly the same horizon, but were not seen together at the same locality. Generally above this horizon the member consists of olive-colored, argillaceous shale. Where the maroon phase occurs the Wea shale below is limy and locally ferruginous and buff. At Paola and south of Hillsdale, and southeast of Osawatomie, the carbonaceous layer occurs at the base of the member. The same facies also occurs at Somerset, northeast of New Lancaster, and at the east side of range 33 east just across the line in Linn County. West of Osawatomie, at Block, south of Beagle, and east of New Lancaster the black shale is absent and its place is taken apparently by a thin layer of maroon clay. The black layer generally contains brachiopods of the orbiculoid type. The Quivira shale is generally about four feet thick, the upper three feet being greenish, argillaceous shale, and the lower foot either black fissile shale or maroon clay.

In Johnson County the Quivira is characteristically an olive-green, limy or argillaceous shale with a carbonaceous layer near the middle. In some parts of northwestern Missouri as well as to the south of Johnson County a maroon shale layer seemingly takes the place of the carbonaceous bed. Along Big Blue river the formation is about five feet thick, increasing northward to eleven feet at Kansas river.

Distribution. The outcrop of the Quivira shale in Miami County is practically coextensive with that of the Drum limestone. In the northern part of the county the formation extends up the valley of the Wea to the center of the north edge of sec. 32, T. 16 S., R. 24 E., and to sec. 35 of the same township. On Bull creek the bed crops out nearly to the center of township 16 south, range 23 east. A reentrant of the Quivira occurs along the north edge of township 18 south, ranges 24, 25 east, extending out of the state into Missouri at the north edge of section 14, township 18 south, range 25 east. The formation reaches nearly to the west line of range 22 east on Marais des Cygnes and Pottawatomie rivers. On Mound creek the Quivira crops out to a point southwest of Beagle.

In Johnson County the Quivira crops out along the valley of Kansas river as far west as Holliday and enters Johnson County along Turkey creek and all of the principal streams in the eastern part of the county.

Detailed sections. Sections of the Quivira shale are given under numbers 1, 8, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43, 48, 50, 52, 55, 65, 66, 67, 68, 78, 92, 98, 99, 101, 106, 109, 117, 129, 131, 132, 136, 142, 150, 155, 151, and 166 at the end of this report.

Drum Limestone

The Drum was named by Adams from Drum creek in the region about Cherryvale and Independence in southeastern Kansas. [Adams, G. I., Stratigraphy and paleontology of the Upper Carboniferous rocks of the Kansas section: U. S. Geol. Survey, Bull. 211, p. 37, 1903.] There is a great deal of variation in the Drum of the type region, for it ranges from eight feet of nonoolitic blue-gray limestone just north of Cherryvale to more than sixty feet of granular and oolitic limestone near Independence. The oolitic part, for which Moore proposes the term Corbin City, from a suburb of Cherryvale, lies unconformably upon the nonoolitic or Cement City member. It seems that the nonoolitic facies is equivalent to only a lower part of the great mass at Independence, and for this reason the upper limit of the Drum varies considerably in age within the type region. Apparently the formation increases in thickness by replacement of the Chanute shale.

In connection with the study of Miami and Johnson counties it .was determined that the unit at Kansas City known as the Cement City limestone is continuous across eastern Kansas with the lower part of the type Drum limestone at Drum creek. The peculiar molluscan fauna of the oolitic facies of the Drum is a facies fauna that is quite as local in its distribution as oolite. Such faunas are far less reliable in correlation than are the faunas of persistent lithologic types. My conclusion that the Cement City is the basal part of the typical Drum was verified in the field by R. C. Moore. From Miami County to Cherryvale the Drum is an obscure unit, exhibiting but poor topographic expression. It is generally a little thicker than two feet.

Lithologic character and thickness. The Drum limestone is one of the most uniform and most easily recognizable units in Miami County. It is well exposed at a number of localities. The formation consists generally of a single layer of massive, fine-grained, drab or brown ferruginous limestone. Locally the upper part of the formation is shaly and granular, and contains a species of Osagia. In some artificial exposures the rock breaks up into very thin beds and shows obscure cross-bedding. A characteristic feature of the bed is the occurrence of small, white crinoid segments scattered rather evenly through the limestone. These are quite noticeable against the brown or buff color of the rock in which they occur. Ramose bryozoans are not uncommon on the weathered surface of the formation. Toward the southern border of Miami County the formation tends to become more coarsely granular. In fresh exposures the rock commonly shows a pale olive-drab or drab color, which is changed to a brown on weathered surfaces. At two localities limestone lentils are associated with the formation. One of these, just west of Somerset on the highway, occurs just above the massive ledge of the Drum, separated from it by a thin shale. This upper limestone, which may be considered a northern equivalent of the Corbin City, is cross-bedded and coarse-grained, and about five feet thick. It was not observed at any other place. At a locality one quarter of a mile south of the NW cor. sec. 7, T. 18 S., R. 25 E., a thin-bedded limestone conglomerate occurs below the Drum, separated from it by the thin black shale of the Quivira. This lentil is about two and one half feet thick at the above locality. Since this lies at the horizon of the Westerville limestone, it is probable that it is a southern representative of that formation.

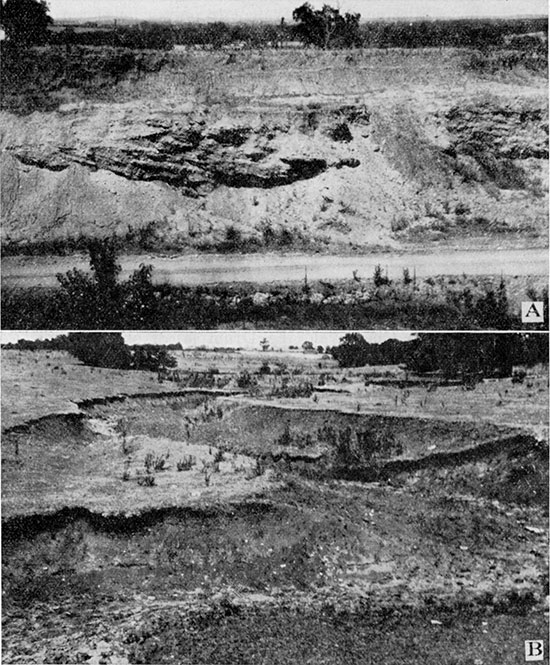

Plate V--A--High terrace gravel, near Holliday, Johnson County. B--Recent gully, middle south side sec. 22, T. 13 S., R. 24 E. Relief about five feet.

Although these local occurrences of limestones associated with the Drum indicate lack of uniform environment before and after deposition of the Cement City member, the member itself shows little irregularity. The greatest thickness occurs in township 18 south, range 22 east near Osawatomie, where the bed ranges from four to six feet. Generally, however, it averages about two and one half feet. The least thickness observed is one foot nine inches. This occurs about one fourth of a mile south of the NW cor. of sec. 7, T. 18 S., R. 25 E. The formation measures as little as two feet at many localities.